BOOTH's PLOT to KIDNAP LINCOLN: Ida Tarbell Speaks Again

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 7 Lincoln's Assassination

LESSON 7: LINCOLN’S GRADE 5-8 ASSASSINATION WWW.PRESIDENTLINCOLN.ORG Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum Objectives • Identify at least three individuals involved in Lincoln’s assassination. • Understand the motivations compelling Booth to assassinate the president. • Define vocabulary relevant to an assassination, conspiracy, and trial. • Assess and interpret the subject matter of an historic photograph or docu- ment. • Appreciate the importance of collecting and preserving primary sources.. • Recognize how primary sources can be used in the understanding and tell- ing of historic stories. INTRODUCTION ohn Wilkes Booth was not the American history had ever been The purpose of this J first person to ever consider assassinated. Still, concern for lesson is to introduce students killing Abraham Lincoln. Death Lincoln’s safety grew as the Civil to the story of Lincoln’s assassi- threats to the President were War continued, and with good nation and those who conspired frequent and common. They reason. Lincoln’s politics, espe- to kill him, the issues dividing came from the disgruntled and cially his stance on slavery, were the United States at that time, the deranged. But no one really divisive. The country was in and the techniques used by li- believed any would be carried turmoil and many blamed Lin- brary and museum professionals out. No prominent figure in coln. in uncovering and interpreting history. Materials • "Analyzing A Photograph Worksheet” (in this lesson plan) • “Analyzing A Document Worksheet" (in this lesson plan) -

Emancipation Proclamation

Abraham Lincoln and the emancipation proclamation with an introduction by Allen C. Guelzo Abraham Lincoln and the emancipation proclamation A Selection of Documents for Teachers with an introduction by Allen C. Guelzo compiled by James G. Basker and Justine Ahlstrom New York 2012 copyright © 2008 19 W. 44th St., Ste. 500, New York, NY 10036 www.gilderlehrman.org isbn 978-1-932821-87-1 cover illustrations: photograph of Abraham Lincoln, by Andrew Gard- ner, printed by Philips and Solomons, 1865 (Gilder Lehrman Collection, GLC05111.01.466); the second page of Abraham Lincoln’s draft of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, September 22, 1862 (New York State Library, see pages 20–23); photograph of a free African American family in Calhoun, Alabama, by Rich- ard Riley, 19th century (GLC05140.02) Many of the documents in this booklet are unique manuscripts from the gilder leh- rman collection identified by the following accession numbers: p8, GLC00590; p10, GLC05302; p12, GLC01264; p14, GLC08588; p27, GLC00742; p28 (bottom), GLC00493.03; p30, GLC05981.09; p32, GLC03790; p34, GLC03229.01; p40, GLC00317.02; p42, GLC08094; p43, GLC00263; p44, GLC06198; p45, GLC06044. Contents Introduction by Allen C. Guelzo ...................................................................... 5 Documents “The monstrous injustice of slavery itself”: Lincoln’s Speech against the Kansas-Nebraska Act in Peoria, Illinois, October 16, 1854. 8 “To contribute an humble mite to that glorious consummation”: Notes by Abraham Lincoln for a Campaign Speech in the Senate Race against Stephen A. Douglas, 1858 ...10 “I have no lawful right to do so”: Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861 .........12 “Adopt gradual abolishment of slavery”: Message from President Lincoln to Congress, March 6, 1862 ...........................................................................................14 “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude . -

Chapter 11: the Civil War, 1861-1865

The Civil War 1861–1865 Why It Matters The Civil War was a milestone in American history. The four-year-long struggle determined the nation’s future. With the North’s victory, slavery was abolished. During the war, the Northern economy grew stronger, while the Southern economy stagnated. Military innovations, including the expanded use of railroads and the telegraph, coupled with a general conscription, made the Civil War the first “modern” war. The Impact Today The outcome of this bloody war permanently changed the nation. • The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery. • The power of the federal government was strengthened. The American Vision Video The Chapter 11 video, “Lincoln and the Civil War,” describes the hardships and struggles that Abraham Lincoln experienced as he led the nation in this time of crisis. 1862 • Confederate loss at Battle of Antietam 1861 halts Lee’s first invasion of the North • Fort Sumter fired upon 1863 • First Battle of Bull Run • Lincoln presents Emancipation Proclamation 1859 • Battle of Gettysburg • John Brown leads raid on federal ▲ arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia Lincoln ▲ 1861–1865 ▲ ▲ 1859 1861 1863 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1861 1862 1863 • Russian serfs • Source of the Nile River • French troops 1859 emancipated by confirmed by John Hanning occupy Mexico • Work on the Suez Czar Alexander II Speke and James A. Grant City Canal begins in Egypt 348 Charge by Don Troiani, 1990, depicts the advance of the Eighth Pennsylvania Cavalry during the Battle of Chancellorsville. 1865 • Lee surrenders to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse • Abraham Lincoln assassinated by John Wilkes Booth 1864 • Fall of Atlanta HISTORY • Sherman marches ▲ A. -

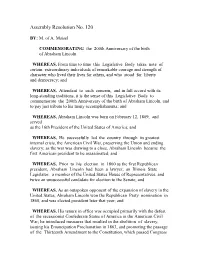

Assembly Resolution No. 120

Assembly Resolution No. 120 BY: M. of A. Maisel COMMEMORATING the 200th Anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln WHEREAS, From time to time this Legislative Body takes note of certain extraordinary individuals of remarkable courage and strength of character who lived their lives for others, and who stood for liberty and democracy; and WHEREAS, Attendant to such concern, and in full accord with its long-standing traditions, it is the sense of this Legislative Body to commemorate the 200th Anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln, and to pay just tribute to his many accomplishments; and WHEREAS, Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, and served as the 16th President of the United States of America; and WHEREAS, He successfully led the country through its greatest internal crisis, the American Civil War, preserving the Union and ending slavery; as the war was drawing to a close, Abraham Lincoln became the first American president to be assassinated; and WHEREAS, Prior to his election in 1860 as the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln had been a lawyer, an Illinois State Legislator, a member of the United States House of Representatives, and twice an unsuccessful candidate for election to the Senate; and WHEREAS, As an outspoken opponent of the expansion of slavery in the United States, Abraham Lincoln won the Republican Party nomination in 1860, and was elected president later that year; and WHEREAS, His tenure in office was occupied primarily with the defeat of the secessionist Confederate States of America in the American Civil War; he introduced measures that resulted in the abolition of slavery, issuing his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and promoting the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which passed Congress before Lincoln's death and was ratified by the States later in 1865; and WHEREAS, Abraham Lincoln closely supervised the victorious war effort, especially the selection of top generals, including Ulysses S. -

Who Was Robert Todd Lincoln?

WHO WAS ROBERT TODD LINCOLN? He was the only child of Abe and Mary Lincoln to survive into adulthood - with his three brothers having died from illness at young ages. Believe it or not, Robert lived until 1926, dying at age 83. But along the way, he sure lived a remarkable life. For starters, he begged his father for a commission to serve in the Civil War, with President Lincoln refusing, saying the loss of two sons (to that point) made risking the loss of a third out of the question. But Robert insisted, saying that if his father didn't help him, he would join on his own and fight with the front line troops; a threat that drove Abe to give in. But you know how clever Abe was. He gave Robert what he wanted, but wired General Grant to assign "Captain Lincoln" to his staff, and to keep him well away from danger. The assignment did, however, result in Robert's being present at Appomattox Court House, during the historic moment of Lee's surrender. Then - the following week, while Robert was at the White House, he was awakened at midnight to be told of his father's shooting, and was present at The Peterson House when his father died. Below are Robert's three brothers; Eddie, Willie, and Tad. Little Eddie died at age 4 in 1850 - probably from thyroid cancer. Willie (in the middle picture) was the most beloved of all the boys. He died in the White House at age 11 in 1862, from what was most likely Typhoid Fever. -

Ford's Theatre, Lincoln's Assassination and Its Aftermath

Narrative Section of a Successful Proposal The attached document contains the narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful proposal may be crafted. Every successful proposal is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the program guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/education/landmarks-american-history- and-culture-workshops-school-teachers for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Seat of War and Peace: The Lincoln Assassination and Its Legacy in the Nation’s Capital Institution: Ford’s Theatre Project Directors: Sarah Jencks and David McKenzie Grant Program: Landmarks of American History and Culture Workshops 400 7th Street, S.W., 4th Floor, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 E [email protected] www.neh.gov 2. Narrative Description 2015 will mark the 150th anniversary of the first assassination of a president—that of President Abraham Lincoln as he watched the play Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre, six blocks from the White House in Washington, D.C. -

Abraham Lincoln Final by William

Abraham Lincoln: “Didn’t Want Slavery” By William Martinez Lones Abraham Lincoln 16th President of the U.S.A. Born:February 12,1809 in Hodgeville, Kentucky Died:April 14,1865 Age:56 Vocab Box: Background Humble → simple or not fancy Chores → work around the house Politics → Activity or power of government Abraham Lincoln was born in Hodgeville, Kentucky, Legislature → the branch of government that writes laws February 12, 1809. His family was poor. They lived in a Term → a length of time in office humble house and the shelter was made out of wood until Abolish → to ban they built a cabin. Abe’s chores were to fish, put traps for rabbits and muskrats and follow bees to the honey tree to get honey. Abe’s parents couldn’t read or write. But Abe studied law, politics, and history when he had time. His first election was as a legislator for the Illinois state legislature. He lost the election but decided to do it again. After he had a lot of jobs in government. He became a member of the Congress and lost his second term because he wanted to abolish slavery. In 1860, he ran for president and lost every Southern state, but he won The Lincolns lived in a cabin like this the election. one. The Civil War and Ending Slavery After Abe became president, the seven Vocab Box: Amendment → a change to the law southern states left the U.S., becoming Emancipation → freedom Confederate States of America (they wanted to Proclamation → when you make a statement keep slavery). -

The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln • 150 Years After Lincoln's Assassination, Equality Is Still a Struggle

Social Science Department United States History I June 8-12 Greetings USI Students! We hope you are safe and well with your families! Below is the lesson plan for this week: Content Standard: Topic 5. The Civil War and Reconstruction: causes and consequences Civil War: Key Battles and Events Practice Standard(s): 1. Develop focused questions or problem statements and conduct inquiries. 2. Organize information and data from multiple primary and secondary sources. 3. Argue or explain conclusions, using valid reasoning and evidence. Weekly Learning Opportunities: 1. Civil War Timeline and Journal Entry Assignment 2. Historical Civil War Speeches and Extension Activity: • Emancipation Proclamation • The Gettysburg Address 3. Newsela Articles: President Lincoln • Time Machine (1865): The assassination of Abraham Lincoln • 150 years after Lincoln's assassination, equality is still a struggle Additional Resources: • Civil War "The True Story of Glory Continues" - 1991 Documentary sequel https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lXyhTnfAV1o • Glory (1989) - Matthew Broderick, Denzel Washington, Cary Elwes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2LP4tPnCZt4 Note to students: Your Social Science teacher will contact you with specifics regarding the above assignments in addition to strategies and recommendations for completion. Please email your teacher with specific questions and/or contact during office hours. Assignment 1: Civil War Battle Timeline Directions: 1. Using this link https://www.historyplace.com/civilwar/, create a timeline featuring the following events: 1. Election of Abraham Lincoln 2. Jefferson Davis named President 3. Battle of Ft. Sumter 4. Battle of Bull Run 5. Battle of Antietam 6. Battle of Fredericksburg 7. Battle of Chancellorsville 8. Battle of Shiloh 9. -

Mary Lincoln Narrative and Chronology

MEET MARY LINCOLN BIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE & CHRONOLOGY WWW.PRESIDENTLINCOLN.ORG Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum MARY TODD’S EARLY LIFE ary Todd was born the finer things in life that allowed to continue her M into a prominent Lex- money bought, among them studies at the Mentelle’s for ington, Kentucky family. Her were beautiful clothes, im- Young Ladies School. Begin- parents, Eliza Ann Parker ported French shoes, elegant ning in 1832, Mary boarded and Robert Smith Todd dinners, a home library and, at Mentelle’s Monday were second cousins, a com- private carriages. through Friday and went mon occurrence in the early home on the weekend even eighteen hundreds. Mary Mary was almost though the school was only was not yet seven when her nine years old when she one and a half miles from her mother died of a bacterial entered the Shelby Female home. Every week, Mary was infection after delivering a Academy, otherwise known brought to and from school son in 1825. Within six as Ward’s. School began at in a coach driven by a family months Mary’s father began 5:00 am, and Mary and Eliza- slave, Nelson. The cost of courting Elizabeth “Betsey” beth “Lizzie” Humphreys room and board for one Humphreys and they were walked the three blocks to year at this exclusive finish- married November 1, 1826. the co-ed academy. Mary ing school was $120. For The six surviving children of was an excellent student and four years, Mary received Eliza and Robert Todd did excelled in reading, writing, instruction in English litera- not take kindly to their new grammar, arithmetic, history, ture, etiquette, conversation, step-mother. -

Was John Wilkes Booth's Conspiracy Successful?

CHAPTER FIVE Was John Wilkes Booth’s Conspiracy Successful? Jake Flack and Sarah Jencks Ford’s Theatre Ford’s Theatre is draped in mourning, 1865. Was John Wilkes Booth’s Conspiracy Successful? • 63 MIDDLE SCHOOL INQUIRY WAS JOHN WILKES BOOTH’S CONSPIRACY SUCCESSFUL? C3 Framework Indicator D2.His.1.6-8 Analyze connections among events and developments in broader historical contexts. Staging the Compelling Question Students will analyze primary source documents related to the Lincoln assassination to construct an argument on the success or failure of Booth’s plan. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 What was the goal of Booth’s What were the the immediate How did Booth’s actions affect conspiracy? results of that plot? Reconstruction and beyond? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Create a list of reasons of why Write a one-paragraph news Make a claim about the effect of Booth might have first wanted to report describing what happened Booth’s actions on Reconstruction. kidnap and then decided to kill immediately after Lincoln’s death. Lincoln and other key government leaders. Featured Sources Featured Sources Featured Sources Source A: Excerpts from Booth’s Source A: Overview of the Source A: Overview of diary assassination aftermath Reconstruction Source B: Excerpts from Lincoln’s Source B: Excerpt from a letter Source B: “President Johnson final speech from Willie Clark Pardoning the Rebels”—Harper’s Source C: Events of April, 1865 Source C: Excerpt from a letter Weekly 1865 Source D: Conspirator biographies from Dudley Avery Source C: “Leaders of the and photos Democratic Party”—Political Cartoon by Thomas Nast Source D: Overview of Lincoln’s legacy Summative Performance Task ARGUMENT: Was John Wilkes Booth’s conspiracy successful? Construct an argument (e.g., detailed outline, poster, essay) that discusses the compelling question using specific claims and relevant evidence from historical sources while acknowledging competing views. -

John Wilkes Booth

Educational materials were developed through the Making Master Teachers in Howard County Program, a partnership between Howard County Public School System and the Center for History Education at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. RS#10 Document I John Wilkes Booth Portrait of John Wilkes Booth Source: U.S. National Archives http://www.archives.gov 1865 Broadside Green Mount Cemetery Source: Library of Congress Baltimore, Maryland http://memory.loc.gov Obelisk (Monument) marking Booth’s family burial plot On April 14, 1865 John Wilkes Booth fatally shot President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre on 10th Street in Washington. The attack came five days after Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. Booth was a Maryland native, respected actor, and Southern sympathizer. During the play, Our American Cousin, he slipped into the president's box and shot Lincoln in the back of the head. Booth shouted, "Sic semper tyrannis! [Thus always to tyrants] The South is avenged!” He jumped onto the stage, breaking his leg. He escaped on horseback. The U.S. Army eventually cornered Booth in a barn near Bowling Green, Virginia. The barn was set on fire. As Booth was fleeing, he was shot and later died. Sensing that an exhibition of Booth’s body might cause a riot, the government had it secretly buried at night in a grave in the yard of the Washington Penitentiary. In 1869, B ooth’s brother, Edwin, asked President Andrew Johnson to release the remains to him for proper burial. Johnson agreed to the request. Booth’s body was moved to Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore and buried in an unmarked grave in the family plot. -

THE LINCOLN ASSASSINATION 1. What Does Lincoln Dream About On

THE LINCOLN ASSASSINATION 1. What does Lincoln dream about on April 11, 1865? 2. Where did John Wilkes Booth shoot Lincoln? 3. Who initially attempted to stop Booth from escaping? 4. What did Booth yell when he landed on the stage of Ford’s Theatre? 5. What do most people remember from Ford’s Theatre that night? 6. Describe what the doctor did that first encountered Lincoln after he had been shot. 7. Where did they take Lincoln? 8. As rumors spread there is talk of another assassination attempt that night on whom? Who is the 2nd assassin that night and how did he attempt to kill his victim? 9. Who was supposed to be killed by the third assassin? Who was the 3rd assassin? 10. What did the police find in the 3rd assassin’s room? 11. Describe Mary Todd Lincoln and Robert Todd Lincoln’s reaction to Abe Lincoln’s current fragile state? 12. When did Abraham Lincoln die? How old was he? What were Edwin Stanton’s last words? 13. How did people respond to this tragic loss? 14. What did the doctors remove when performing an autopsy on Lincoln's body? 15. Where will Lincoln be buried? 16. Who saved Robert Todd Lincoln’s life at one point? 17. Who was riding with Booth that night? Who did Booth seek medical attention from that night? 18. When did the doctor find out about the assassination? What did the doctor do with this information? 19. How did Booth respond to the newspapers reporting on his assassination of Lincoln? 20.