Chennai, India ⇑ Rashmi Krishnamurthy A, , Kevin C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T.Y.B.A. Paper Iv Geography of Settlement © University of Mumbai

31 T.Y.B.A. PAPER IV GEOGRAPHY OF SETTLEMENT © UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Dr. Sanjay Deshmukh Vice Chancellor, University of Mumbai Dr.AmbujaSalgaonkar Dr.DhaneswarHarichandan Incharge Director, Incharge Study Material Section, IDOL, University of Mumbai IDOL, University of Mumbai Programme Co-ordinator : Anil R. Bankar Asst. Prof. CumAsst. Director, IDOL, University of Mumbai. Course Co-ordinator : Ajit G.Patil IDOL, Universityof Mumbai. Editor : Dr. Maushmi Datta Associated Prof, Dept. of Geography, N.K. College, Malad, Mumbai Course Writer : Dr. Hemant M. Pednekar Principal, Arts, Science & Commerce College, Onde, Vikramgad : Dr. R.B. Patil H.O.D. of Geography PondaghatArts & Commerce College. Kankavli : Dr. ShivramA. Thakur H.O.D. of Geography, S.P.K. Mahavidyalaya, Sawantiwadi : Dr. Sumedha Duri Asst. Prof. Dept. of Geography Dr. J.B. Naik, Arts & Commerce College & RPD Junior College, Sawantwadi May, 2017 T.Y.B.A. PAPER - IV,GEOGRAPHYOFSETTLEMENT Published by : Incharge Director Institute of Distance and Open Learning , University of Mumbai, Vidyanagari, Mumbai - 400 098. DTP Composed : Ashwini Arts Gurukripa Chawl, M.C. Chagla Marg, Bamanwada, Vile Parle (E), Mumbai - 400 099. Printed by : CONTENTS Unit No. Title Page No. 1 Geography of Rural Settlement 1 2. Factors of Affecting Rural Settlements 20 3. Hierarchy of Rural Settlements 41 4. Changing pattern of Rural Land use 57 5. Integrated Rural Development Programme and Self DevelopmentProgramme 73 6. Geography of Urban Settlement 83 7. Factors Affecting Urbanisation 103 8. Types of -

Environmental and Social Systems Assessment Report March 2021

Chennai City Partnership Program for Results Environmental and Social Systems Assessment Report March 2021 The World Bank, India 1 2 List of Abbreviations AIIB Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank AMRUT Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission BMW Bio-Medical Waste BOD Biological Oxygen Demand C&D Construction & Debris CBMWTF Common Bio-medical Waste Treatment and Disposal Facility CEEPHO Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation CETP Common Effluent Treatment Plant CMA Chennai Metropolitan Area CMDA Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority CMWSSB Chennai Metro Water Supply and Sewage Board COD Chemical Oxygen Demand COE Consent to Establish COO Consent to Operate CPCB Central Pollution Control Board CRZ Coastal Regulation Zone CSCL Chennai Smart City Limited CSNA Capacity Strengthening Needs Assessment CUMTA Chennai Unified Metropolitan Transport Authority CZMA Coastal Zone Management Authority dBA A-weighted decibels DoE Department of Environment DPR Detailed Project Report E & S Environmental & Social E(S)IA Environmental (and Social) Impact Assessment E(S)MP Environmental (and Social) Management Plan EHS Environmental, Health & Safety EP Environment Protection (Act) ESSA Environmental and Social Systems Assessment GCC Greater Chennai Corporation GDP Gross Domestic Product GL Ground Level GoTN Government of Tamil Nadu GRM Grievance Redressal Mechanism HR Human Resources IEC Information, Education and Communication ICC Internal Complaints Committee JNNRUM Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission -

April Newsletter of Turyaa

" I f y o u r a c t i o n s i n s p i r e o t h e r s t o d r e a m m o r e , l e a r n m o r e a n d d o m o r e , y o u a r e a L E A D E R . " - - J o h n Q u i n c y A d a m s 1 4 4 / 7 , R a j i v G a n d h i S a l a i ( O M R ) , C h e n n a i - 6 0 0 0 4 1 @ + 9 1 4 4 6 6 9 7 0 0 0 0 w w w . t u r y a a h o t e l s . c o m / c h e n n a i w w w . a i t k e n s p e n c e h o t e l s . c o m A P R I L 2 0 1 9 , I S S U E 1 T U R Y A A C H E N N A I - P A G E 1 It is our utmost pleasure to introduce to you the Turyaa's Newsletter. We have crafted this letter which shall not just present the happenings of Turyaa Chennai but also the buzz around the city for the month. The newsletter shall also cover the tourism section for the travelers who love to explore. -

District Statistical Hand Book Chennai District 2016-2017

Government of Tamil Nadu Department of Economics and Statistics DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK CHENNAI DISTRICT 2016-2017 Chennai Airport Chennai Ennoor Horbour INDEX PAGE NO “A VIEW ON ORGIN OF CHENNAI DISTRICT 1 - 31 STATISTICAL HANDBOOK IN TABULAR FORM 32- 114 STATISTICAL TABLES CONTENTS 1. AREA AND POPULATION 1.1 Area, Population, Literate, SCs and STs- Sex wise by Blocks and Municipalities 32 1.2 Population by Broad Industrial categories of Workers. 33 1.3 Population by Religion 34 1.4 Population by Age Groups 34 1.5 Population of the District-Decennial Growth 35 1.6 Salient features of 1991 Census – Block and Municipality wise. 35 2. CLIMATE AND RAINFALL 2.1 Monthly Rainfall Data . 36 2.2 Seasonwise Rainfall 37 2.3 Time Series Date of Rainfall by seasons 38 2.4 Monthly Rainfall from April 2015 to March 2016 39 3. AGRICULTURE - Not Applicable for Chennai District 3.1 Soil Classification (with illustration by map) 3.2 Land Utilisation 3.3 Area and Production of Crops 3.4 Agricultural Machinery and Implements 3.5 Number and Area of Operational Holdings 3.6 Consumption of Chemical Fertilisers and Pesticides 3.7 Regulated Markets 3.8 Crop Insurance Scheme 3.9 Sericulture i 4. IRRIGATION - Not Applicable for Chennai District 4.1 Sources of Water Supply with Command Area – Blockwise. 4.2 Actual Area Irrigated (Net and Gross) by sources. 4.3 Area Irrigated by Crops. 4.4 Details of Dams, Tanks, Wells and Borewells. 5. ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 5.1 Livestock Population 40 5.2 Veterinary Institutions and Animals treated – Blockwise. -

Chennai District Origin of Chennai

DISTRICT PROFILE - 2017 CHENNAI DISTRICT ORIGIN OF CHENNAI Chennai, originally known as Madras Patnam, was located in the province of Tondaimandalam, an area lying between Pennar river of Nellore and the Pennar river of Cuddalore. The capital of the province was Kancheepuram.Tondaimandalam was ruled in the 2nd century A.D. by Tondaiman Ilam Tiraiyan, who was a representative of the Chola family at Kanchipuram. It is believed that Ilam Tiraiyan must have subdued Kurumbas, the original inhabitants of the region and established his rule over Tondaimandalam Chennai also known as Madras is the capital city of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Located on the Coromandel Coast off the Bay of Bengal, it is a major commercial, cultural, economic and educational center in South India. It is also known as the "Cultural Capital of South India" The area around Chennai had been part of successive South Indian kingdoms through centuries. The recorded history of the city began in the colonial times, specifically with the arrival of British East India Company and the establishment of Fort St. George in 1644. On Chennai's way to become a major naval port and presidency city by late eighteenth century. Following the independence of India, Chennai became the capital of Tamil Nadu and an important centre of regional politics that tended to bank on the Dravidian identity of the populace. According to the provisional results of 2011 census, the city had 4.68 million residents making it the sixth most populous city in India; the urban agglomeration, which comprises the city and its suburbs, was home to approximately 8.9 million, making it the fourth most populous metropolitan area in the country and 31st largest urban area in the world. -

Chennai City Has Been Divided Into Three Ranges and Further Into Nine Districts for the Purpose of Maintaining Law and Order

- 1 - Chennai Police RTI Manual Chennai Police RTI Manual Particulars of organization, functions and duties [Section 4(1) (b) (i)] 1) Aims and objectives of the organization:- To enforce the law fairly and firmly: to prevent crime; to bring to justice those who break the law; to maintain peace in partnership with the Community; to help and ensure the safety and security of the people. 2) Mission / Vision:- To enforce law fairly and firmly; to prevent Crime; to bring to justice those who break the law; to maintain peace in partnership with the people; to help and ensure the safety and security of the people and to be seen by the people that we do all these with integrity, common sense and sound judgment. We shall be Compassionate, Courteous and patient, acting without fear, favour or prejudice to the rights of the people. 3. Brief History of Chennai Police The year 1856 is a land – mark in the annals of the Madras Town Police, when Act XIII of 1856 viz an Act regulating the Police of the Towns of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay and the several stations of the settlement of Prince of Wales Island, Singapore and Malaysia was enacted by the Governor – General of India in council. By this Act, the head of the Town Police was designed as the Commissioner of Police. The new force was organized very much on the model of the Metropolitan Police of London (U.K.) which came into existence in the year 1829 after enactment of the Metropolitan Police Act by Sir Robert Peel, Home Secretary Lt. -

New Chennai Chennai, Formerly Madras, City, Capital of Tamil Nadu

1 Older Chennai New chennai ➢ Chennai, formerly Madras, city, capital of Tamil Nadu state. Known as the “Gateway to South India. ➢ Chennai is the 400 year old city is the 31st largest metropolitan area in the world. ➢ Chennai is the India’s fifth largest city. History of Chennai: ➢ Originally known as "Madras", was located in the province of Tondaimandalam, an area lying between Penna River of Nellore and the Ponnaiyar river of Cuddalore. t.me/shanawithu t.me/civilcentric Brother Mentor Contact No:9500833976 2 ➢ The name Madras was Derived from Madrasan a fisherman head who lived in coastal area of Madras. ➢ The Original Name of Madras Is Puliyur kottam which is 2000 year old Tamil ancient name. ➢ Tondaimandalam was ruled in the 2nd century CE by Tondaiman Ilam Tiraiyan who was a representative of the Chola family at Kanchipuram. ➢ Chennai was ruled by cholas, satavahanas,pallavas and Pandiyas. ➢ The Vijayanagar rulers appointed chieftain known as Nayaks who ruled over the different regions of the province almost independently. ➢ Damarla Venkatapathy Nayak, an influential chieftain under Venkata III, who was in-charge of the area of present Chennai city, gave the grant of a piece of land lying between the river Cooum almost at the point it enters the sea and another river known as Egmore river to the English in 1639. ➢ On this piece of waste land was founded the Fort St. George exactly for business considerations. ➢ In honour of Chennappa Nayak, father of Venkatapathy Nayak, who controlled the entire coastal country from Pulicat in the north to the Portuguese settlement of Santhome, the settlement which had grown up around Fort St. -

50 Golden Years of the C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation, Chennai

50 Years of The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation of THE C.P. RAMASWAMI AIYAR FOUNDATION The Grove, 1 Eldams Road, Chennai 600018 www.cprafoundation.org 1 50 Years of The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation © The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 2016 The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road Chennai 600 018 Tel : 2434 1778 / 2435 9366 Fax : 91-44-24351022 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.cprfoundation.org 2 50 Years of The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation Contents 1. Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar 7 2. The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 15 3. C.P. Art Centre 37 4. C.P.R. Institute of Indological Research 76 5. Saraswathi Kendra Learning Centre for Children 107 6. The Grove School 117 7. Rangammal Vidyalaya Nursery and Primary School, Kanchipuram 121 8. C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Memorial Nursery and Primary School, Kumbakonam 122 9. Each One Teach One 123 10. Training Adolescent Girls in Traditional Drawing and Painting 127 11. Vocational Courses 129 12. Saraswathi Award and the Navaratri Festival of Music 131 13. Women’s Development 132 14. Shakunthala Jagannathan Museum of Kanchi, Kanchipuram 133 15. Temple of Varahishwara in Damal, Kanchipuram 139 16. Tribal Welfare 141 17. Inter-School Sanskrit Drama Competition 147 18. Revival of Folk Art Forms in Schools 148 19. Health and Nutrition 153 20. Tsunami Relief and Rehabilitation 154 21. C.P.R. Environmental Education Centre 157 22. National Environmental Awareness Campaign 176 23. Kindness Kids 178 24. Clean Chennai Green Chennai 180 3 50 Years of The C.P. -

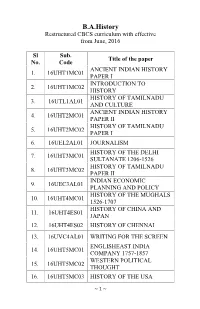

B.A.History Restructured CBCS Curriculum with Effective from June, 2016

B.A.History Restructured CBCS curriculum with effective from June, 2016 Sl Sub. Title of the paper No. Code ANCIENT INDIAN HISTORY 1. 16UHT1MC01 PAPER I INTRODUCTION TO 2. 16UHT1MC02 HISTORY HISTORY OF TAMILNADU 3. 16UTL1AL01 AND CULTURE ANCIENT INDIAN HISTORY 4. 16UHT2MC01 PAPER II HISTORY OF TAMILNADU 5. 16UHT2MC02 PAPER I 6. 16UEL2AL01 JOURNALISM HISTORY OF THE DELHI 7. 16UHT3MC01 SULTANATE 1206-1526 HISTORY OF TAMILNADU 8. 16UHT3MC02 PAPER II INDIAN ECONOMIC 9. 16UEC3AL01 PLANNING AND POLICY HISTORY OF THE MUGHALS 10. 16UHT4MC01 1526-1707 HISTORY OF CHINA AND 11. 16UHT4ES01 JAPAN 12. 16UHT4ES02 HISTORY OF CHENNAI 13. 16UVC4AL01 WRITING FOR THE SCREEN ENGLISHEAST INDIA 14. 16UHT5MC01 COMPANY 1757-1857 WESTERN POLITICAL 15. 16UHT5MC02 THOUGHT 16. 16UHT5MC03 HISTORY OF THE USA ~ 1 ~ HISTORY OF THE SOUTH 17. 16UHT5ES01 EAST ASIA 18. 16UHT5ES02 NEIGHBOURS OF INDIA PRINCIPLES OF 19. 16UHT5SK01 ARCHAEOLOGY AND MUSEOLOGY 20. 16UHT5SK02 TRAVEL AND TOURISM INDIAN FREEDOM 21. 16UHT6MC01 MOVEMENT CONTEMPORARY INDIA 22. 16UHT6MC02 197-2000 HISTORY OF EUROPE 1789- 23. 16UHT6MC03 1955 24. 16UHT6MC04 HISTORIOGRAPHY 25. 16UHT6MS01 SUBALTERN STUDIES CONTEMPORARY 26. 16UHT6MS02 STRATEGICAL STUDIES ~ 2 ~ 16UHT1MC01 ANCIENT INDIAN HISTORY PAPER – I SEMESTER I CREDITS 6 CATEGORY MC NO.OF HOURS/ WEEK 6 Objectives: 1. To familiarise the basic features of Indian culture and to learn the socio-economic and political development 2. To discuss the growth and development of religion in ancient India. Unit I: Sources: Archaeological sources: Literary sources: Foreign accounts: Greek, Chinese and Arab writers. Importance of Sources- Pre-history and Proto-history - Geographical features - hunting and gathering (Paleolithic and Mesolithic) - Beginning of agriculture (Neolithic and Chalcolithic). -

Infrastructures with a Pinch of Salt: Comparative Techno-Politics of Desalination in Chennai and London

Infrastructures with a Pinch of Salt: Comparative techno-politics of desalination in Chennai and London Thesis submitted to University College London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Niranjana Ramesh Department of Geography University College London April 2018 DECLARATION I, Niranjana Ramesh confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Infrastructures, being technological networks that form the structural and social scaffolding of cities, have been symbiotic with modern urban development. Building on their socio-technical character, this thesis seeks to understand the technological mediation of political formations and environmental knowledges that shape notions of urban sustainability. It takes as its point of departure the construction of reverse osmosis desalination plants to augment water supply in two cities across the global South and North – Chennai, India and London, UK. It uses the analytic of infrastructure to excavate the complex reasons as to why and how desalination plants came to be built in these cities. Over a period of 10 months, oral and documentary narratives were gathered from institutions, professionals and citizens involved in water supply and access in the two cities. Based on a comparative reading of these texts and ethnographic field notes, the thesis focuses on the state and engineering practices as significant determinants of urban techno-natures. It demonstrates that infrastructures provide a mode of articulating statehood through mediation between technology, nature and society. It traces how engineers and other water professionals, through their everyday work, socialise those water systems, cultivating popular environmental knowledges. -

The Situation Analysis of Migrant Population Residing in the Flood Prone Areas in Chennai

Anthropologist, 34(1-3): 39-47 (2018) © Kamla-Raj 2018 DOI: 10.31901/24566802.2018/34.1-3.2024 The Situation Analysis of Migrant Population Residing in the Flood Prone Areas in Chennai S. Keerthy1 and D. Praveen Sam2 Department of English, SSN College of Engineering, Kalavakkam 603 110, Tamil Nadu, India E-mail: 1<[email protected]>, 2<[email protected]> KEYWORDS Annual Floods. Anti-migrant Sentiment. Disaster Management. Discrimination. Migrants. ABSTRACT Many people from other states in India come to Tamil Nadu to make a living. This contributes to the escalation in floating population in the city each year as it is the State capital and hub of all paramount economical activities. As the city-proper has dense constructed buildings with its local population residing, this migrant population is bound to reside mostly in the flood prone areas in the city and its suburbs. Through unplanned settlements of migrants in these areas, they face the menace of annual inundation during the monsoon considerably more comparing the natives because of various reasons. This study focuses on the life situation analysis of the migrant population who are residing in the flood prone areas in Chennai. It also aims at collecting various socio- economic, socio-political and socio-ecological facets of these migrants to study their living conditions and welfare facilities available to them, as against various legislative provisions. INTRODUCTION the urban agglomeration of Chennai, which typ- ically includes Chennai’s population in addition Since the beginning of the 20th century, so- to adjacent suburban area. Within a century and cial scientists had analyzed one of the major a half, Chennai has grown 26 fold times in popu- determinants of migration is urbanization, while lation. -

Impact of Urbanization on Rivers of Chennai KAVITHA

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 5, May-2013 396 ISSN 2229-5518 Impact of urbanization on rivers of Chennai KAVITHA. A. Abstract: Water has become the fundamental requirement for people across all cultures and regions not just for drinking or cleaning purposes but for ritual or recreation people seek water’s edge. While reading the record of civilization the events and developments that have occurred along the world’s coasts, rivers, bays, and lakes depicts the involvement and importance of water bodies. It is quite amazing, and interesting to ponder on the numerous characteristics of this single body called ‘water’. Water – a solvent, Water – a cleanser, Water – Quencher of thirst, Water – a coolant, Water – a compound from which every organism is created. Most of our activities have had an inseparable impact upon the Rivers. We depend on these water bodies for transportation and commerce, to carry goods, provide food and other substances across nations, and, to carry away our wastes. Centuries of such water treatment have shown their effect most acutely on urban rivers. Many communities in the past began to observe urban waterfront areas as possible assets rather than treating them as valuable resources. This careless attitude amongst people started to wide spread across different places at different times leading to major deterioration and pollution of these resources. Objective: This paper involves in study of urban rivers which was once a natural source for drinking and other activities now because of urbanization it had turned in to a drainage ditch. The focus is more on the reasons for the transformations, their impacts and some design solutions with River Cooum as a case.