Infrastructures with a Pinch of Salt: Comparative Techno-Politics of Desalination in Chennai and London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zooplankton Diversity of Freshwater Lakes of Chennai, Tamil Nadu with Reference to Ecosystem Attributes

International Journal of Int. J. of Life Science, 2019; 7 (2):236-248 Life Science ISSN:2320-7817(p) | 2320-964X(o) International Peer Reviewed Open Access Refereed Journal Original Article Open Access Zooplankton diversity of freshwater lakes of Chennai, Tamil Nadu with reference to ecosystem attributes K. Altaff* Department of Marine Biotechnology, AMET University, Chennai, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Manuscript details: ABSTRACT Received: 18.04.2019 Zooplankton diversity of twelve water bodies of Chennai with reference to Accepted: 05.05.2019 variation during pre-monsoon, monsoon, post-monsoon and summer Published: 20.06.2019 seasons is investigated and reported. Out of 49 zooplankton species recorded, 27 species belonged to Rotifera, 10 species to Cladocera, 9 Editor: Dr. Arvind Chavhan species to Copepoda and 3 species to Ostracoda. The Rotifers dominated compared to all other zooplankton groups in all the seasons. However, the Cite this article as: diversity of zooplankton varied from season to season and the maximum Altaff K (2019) Zooplankton diversity was recorded in pre- monsoon season while minimum was diversity of freshwater lakes of observed in monsoon season. The common and abundant zooplankton in Chennai, Tamil Nadu with reference these water bodies were Brachionus calyciflorus, Brchionus falcatus, to ecosystem attributes, Int. J. of. Life Brachionus rubens, Asplancna brightwelli and Lecane papuana (Rotifers), Science, Volume 7(2): 236-248. Macrothrix spinosa, Ceriodaphnia cornuta, Diaphnosoma sarsi and Moina micrura (Cladocerans), Mesocyclops aspericornis Thermocyclops decipiens Copyright: © Author, This is an and Sinodiaptomus (Rhinediaptomus) indicus (Copepods) and Stenocypris open access article under the terms major (Ostracod). The density of the zooplankton was high during pre- of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial - No monsoon and post-monsoon period than monsoon and summer seasons. -

Rmk College of Engineering and Technology Rsm Nagar, Puduvoyal – 601 203

RMK COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY RSM NAGAR, PUDUVOYAL – 601 203 DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS ENGINEERING JULY 2012 to DECEMBER 2012 STAFF ACTIVITIES Dr. N.M. Jothi Swaroopan, Prof. / EEE was honoured the title “Joint Secretary” by IET (UK)-YPS, Chennai in the year 2012. FACULTY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS Mr. L.Umasankar, Ms.T.J. Catherine and Mr. N.Hariharan attended one day national level Faculty Development Program on Power system analysis co- ordinate by Dr.N.M.Jothiswaroopan, Conducted bt Anna university at RMKEC, between 29-11-12 and 07-12-12. Dr. N. Kalaiarasi, Dr.N.M.Jothiswaroopan, Ms.T.J. Catherine, Mr.J.Prakash and Ms. R.Shimila attended one day national level Faculty Development Program on Research Methodologies, Conducted by Mechanical Department, RMKCET and ISTE at RMKCET, on 3-11-12. Ms. R.Umadevi, Ms.T.J. Catherine, Mr.S.Muthukumar and Ms. R.Shimila attended one day Training Program on Internal Audit, Conducted by BMQR at RMKCET, on 20-11- 12. WORKSHOPS Mr. Muthu kumar, Asst. Prof. / EEE attended One day national level workshop on NLP Conducted by EXCEL HR, on 23-09-2012. Ms. Catherene, Asst. Prof. / EEE attended Two days national level Workshop on PID Controllers Conducted by Anna university at MIT (AU) Chennai, between 29-09-2012 and 30-09-2012. Dr. N. Kalaiarasi, Dr.N.M.Jothiswaroopan, Ms. R.Umadevi, Ms.T.J. Catherine, Mr. N.Hariharan, Ms. R.Shimila, Mr.S.Muthukumar, Ms. D.Nageswari, Mr. K.Gunalan, Mr. K.Dilawar Basha and Ms.R. Kavitha attended 2 days national level workshop on optimization techniques on real time implementation co- ordinated by Mr. -

T.Y.B.A. Paper Iv Geography of Settlement © University of Mumbai

31 T.Y.B.A. PAPER IV GEOGRAPHY OF SETTLEMENT © UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Dr. Sanjay Deshmukh Vice Chancellor, University of Mumbai Dr.AmbujaSalgaonkar Dr.DhaneswarHarichandan Incharge Director, Incharge Study Material Section, IDOL, University of Mumbai IDOL, University of Mumbai Programme Co-ordinator : Anil R. Bankar Asst. Prof. CumAsst. Director, IDOL, University of Mumbai. Course Co-ordinator : Ajit G.Patil IDOL, Universityof Mumbai. Editor : Dr. Maushmi Datta Associated Prof, Dept. of Geography, N.K. College, Malad, Mumbai Course Writer : Dr. Hemant M. Pednekar Principal, Arts, Science & Commerce College, Onde, Vikramgad : Dr. R.B. Patil H.O.D. of Geography PondaghatArts & Commerce College. Kankavli : Dr. ShivramA. Thakur H.O.D. of Geography, S.P.K. Mahavidyalaya, Sawantiwadi : Dr. Sumedha Duri Asst. Prof. Dept. of Geography Dr. J.B. Naik, Arts & Commerce College & RPD Junior College, Sawantwadi May, 2017 T.Y.B.A. PAPER - IV,GEOGRAPHYOFSETTLEMENT Published by : Incharge Director Institute of Distance and Open Learning , University of Mumbai, Vidyanagari, Mumbai - 400 098. DTP Composed : Ashwini Arts Gurukripa Chawl, M.C. Chagla Marg, Bamanwada, Vile Parle (E), Mumbai - 400 099. Printed by : CONTENTS Unit No. Title Page No. 1 Geography of Rural Settlement 1 2. Factors of Affecting Rural Settlements 20 3. Hierarchy of Rural Settlements 41 4. Changing pattern of Rural Land use 57 5. Integrated Rural Development Programme and Self DevelopmentProgramme 73 6. Geography of Urban Settlement 83 7. Factors Affecting Urbanisation 103 8. Types of -

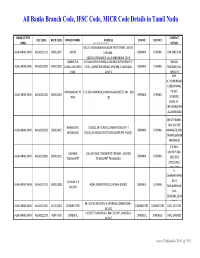

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. 243 to BE ANSWERED on 10Th JULY, 2019

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY (DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE) LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. 243 TO BE ANSWERED ON 10th JULY, 2019 SETTING UP OF A BRANCH OF SPICES BOARD *243. SHRI K. NAVASKANI: Will the Minister of COMMERCE & INDUSTRY (वािण�यएवं उ�ोग मं�ी ) be pleased to state: (a)whether the Government proposes to set up a branch of Spices Board at Paramakudi in Tamil Nadu considering very high production of Chilli and Pepper at Paramakudi; (b)if so, the details thereof; and (c)if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER okf.kT; ,oa m|ksx ea=h ( Jh ih;w’k xks;y ) THE MINISTER OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY (SHRI PIYUSH GOYAL) (a)to (c): A Statement is laid on the Table of the House. ***** STATEMENT REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PARTS (a) to (c)OF LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. 243 FOR ANSWER ON 10th JULY,2019 REGARDING “SETTING UP OF A BRANCH OF SPICES BOARD”. (a)&(b): There is no proposal to set up a branch of Spices Board at Paramakudi in Tamil Nadu. (c): Spices Board is a Statutory Organization set up under the Spices Board Act,1986 for the development of export of spices and for the control of cardamom industry including the control of cultivation of cardamom and matters connected therewith. The mandate for production, development, research and domestic marketing of spices other than cardamom is with the State Agriculture/ Horticulture Departments and the Union Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare. At present, the Spices Board has three Regional Offices at Chennai, Bodinayakanur and Erode. -

SBIOA NEWS BULLETIN from SBI OFFICERS’ ASSOCIATION (CHENNAI CIRCLE)

SBIOA NEWS BULLETIN From SBI OFFICERS’ ASSOCIATION (CHENNAI CIRCLE) : 86, Rajaji Salai, Chennai - 600 001. : 044-25261013 (Housing) : 044-25227170/25228773 : [email protected] : 044-25220225 (For Internal Circulation only) September - 2020 So powerful is the light of unity that it can illuminate the whole earth. Baha'U'Llah Dear Comrade, As per the clarion call given by the UFBU & AIBOC, we were on war path during the months of January/February for our reasonable demands of early reasonable wage settlement, Updation of Pension/Family Pension, 5 days banking, Regulated Working hours for officers etc. and the demonstrations, strike on 31st January and 1st February have been a great success on account of the unity and solidarity shown by the rank and file of our association. Comrades, besides strike actions and other agitation programmes like demonstration, poster campaign, mass signature campaign, Your are well aware of the rapid spread of protest rallies, black badge wearing, candlelight pandemic disease COVID 19 across our Nation protest, press meet and dharna which are on since 23.03.2020 and Government of India and specific dates, UFBU has given a clarion call for Government of Tamilnadu is taking all 'withdrawal of extra cooperation. All the necessary steps to ensure that we are prepared programmes declared by the UFBU are well to face the challenge and threat posed by successfully implemented by your vigor, zeal the growing pandemic of COVID 19 – the and rock like solidarity. Corona Virus. The most important factor in preventing the spread of the Virus locally is to On 29th February 2020, another round of empower the citizens with the right information negotiation took place. -

Environmental and Social Systems Assessment Report March 2021

Chennai City Partnership Program for Results Environmental and Social Systems Assessment Report March 2021 The World Bank, India 1 2 List of Abbreviations AIIB Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank AMRUT Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission BMW Bio-Medical Waste BOD Biological Oxygen Demand C&D Construction & Debris CBMWTF Common Bio-medical Waste Treatment and Disposal Facility CEEPHO Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation CETP Common Effluent Treatment Plant CMA Chennai Metropolitan Area CMDA Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority CMWSSB Chennai Metro Water Supply and Sewage Board COD Chemical Oxygen Demand COE Consent to Establish COO Consent to Operate CPCB Central Pollution Control Board CRZ Coastal Regulation Zone CSCL Chennai Smart City Limited CSNA Capacity Strengthening Needs Assessment CUMTA Chennai Unified Metropolitan Transport Authority CZMA Coastal Zone Management Authority dBA A-weighted decibels DoE Department of Environment DPR Detailed Project Report E & S Environmental & Social E(S)IA Environmental (and Social) Impact Assessment E(S)MP Environmental (and Social) Management Plan EHS Environmental, Health & Safety EP Environment Protection (Act) ESSA Environmental and Social Systems Assessment GCC Greater Chennai Corporation GDP Gross Domestic Product GL Ground Level GoTN Government of Tamil Nadu GRM Grievance Redressal Mechanism HR Human Resources IEC Information, Education and Communication ICC Internal Complaints Committee JNNRUM Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission -

46 Assessing Disaste

[Sharmila, 4(8): August, 2015] ISSN: 2277-9655 (I2OR), Publication Impact Factor: 3.785 IJESRT INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGINEERING SCIENCES & RESEARCH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSING DISASTER IN TANK COMMAND AREAS OF COOUM BASIN USING IRS DATA S.Sharmila*,Dr.R.Latha, Mrs.Anandhi *Research Scholar,St.Peter’s University, India Professor,St.Peter’s University, India Assistant Professor,Idhaya College Of Arts & Science, India ABSTRACT Chennai has a metropolitan population of 8.24 million as per 2011 census and Chennai lacks a perennial water source. Meeting need of water requirements for the population is an arduous task. Although three rivers flow through the metropolitan region and drain into the Bay of Bengal, Chennai has historically relied on annual monsoon rains to replenish its Tanks and Reservoirs as the tanks are silted up or encroached and the river banks are invaded by building activity, drying up due to neglect of tank bunds and loss of their capacity to store rain water, rivers have only source from sewerage water from the buildings and establishments which polluted the river and made it a big surface water sewage system. The area covering Cooum and allied interlinked Kusatalai, Palar and Adayar basins should be considered as Chennai Water supply basin for planning and implementing projects for the future demands by harvesting the monsoon rains in these basins. The concept of watershed delineation in to micro watersheds, use of satellite data bike IRS III(Indian Remote Sensing) and new generation high resolution satellite data has been illustrated in this paper. This paper will make one to understand the past glory of cooum maintained by ancient living people from 5000 years and how our greed to expand without proper hydrological modeling. -

Impact of Genotoxic Contaminants on DNA Integrity of Copepod from Freshwater Bodies in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

ntal & A me na n ly o t ir ic Jeyam and Ramanibai., J Environ Anal Toxicol 2017, 7:3 v a n l T E o Journal of f x DOI: 10.4172/2161-0525.1000464 o i l c o a n l o r g u y o J Environmental & Analytical Toxicology ISSN: 2161-0525 ResearchResearch Article Article Open Accesss Impact of Genotoxic Contaminants on DNA Integrity of Copepod from Freshwater Bodies in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Gomathi Jeyam M and Ramanibai R* Department of Zoology, University of Madras, Guindy Campus, Chennai-25, India Abstract In the present study, we evaluated the DNA damage of freshwater copepod Mesocyclops aspericornis collected from Chembarambakkam, Velachery and Retteri Lake during Premonsoon(PRM) and Post-monsoon (POM) by alkaline comet assay. The highest DNA integrity was observed at Velachery Lake (21.52 ± 0.31 Mean % Tail DNA) followed by Retteri Lake (13.84 ± 0.019 Mean % Tail DNA) during both season, whereas the lowest DNA integrity occurred at Chembarambakkam (0.16 ± 0.14 Mean % Tail) and identified as the reference site. The single cell gel electrophoresis of M. aspericornis clearly showed relatively higher olive tail moment from the contaminated sites Velachery and Retteri Lake (4.66 ± 0.055; 1.42 ± 0.12). During study period we observed the lowest pH and dissolved oxygen levels in the contaminated sites than the reference site. Moreover high level of genotoxic contaminants especially heavy metals (Zn, Cr, Mn, Pd, Ni, Cu, Co) are widespread in all sites, which could be mainly attributed to the high integrity of DNA in freshwater copepod. -

April Newsletter of Turyaa

" I f y o u r a c t i o n s i n s p i r e o t h e r s t o d r e a m m o r e , l e a r n m o r e a n d d o m o r e , y o u a r e a L E A D E R . " - - J o h n Q u i n c y A d a m s 1 4 4 / 7 , R a j i v G a n d h i S a l a i ( O M R ) , C h e n n a i - 6 0 0 0 4 1 @ + 9 1 4 4 6 6 9 7 0 0 0 0 w w w . t u r y a a h o t e l s . c o m / c h e n n a i w w w . a i t k e n s p e n c e h o t e l s . c o m A P R I L 2 0 1 9 , I S S U E 1 T U R Y A A C H E N N A I - P A G E 1 It is our utmost pleasure to introduce to you the Turyaa's Newsletter. We have crafted this letter which shall not just present the happenings of Turyaa Chennai but also the buzz around the city for the month. The newsletter shall also cover the tourism section for the travelers who love to explore. -

ICF-Integral News June 2017 Issue Final

The Prestigious Global Green Award - 2014 June-2017 Issue# 140 Chief Editor: K.Ravi, SSE / Shop-80 Associate Editors: M.A.Jaishankar, SSE / Project A.R.S.Ravindra, SSE / Project R.Mehalan, SE / IT R.Thilak, Tech-III / Shop-80 Advisors: S.Muthukumar, Dy. CME / SR B.Chandrasekaran, Dy. CME / D K.N.Mohan, PE / PR / S R.Srinivasan, APE / PR / F Ÿ ICF has been rated “GreenCo Silver” by the RECENT IMPROVEMENTS IN ICF COACHES Greenco Assessment panel, Confederation of A special filler used for Indian Industry - Godrej application on dents, gaps and Green Business Centre, welding joints on Kolkata H y d e r a b a d , i n Metro Coaches to improve the accordance with the surface is now used on LHB Greenco rating system. coaches. Ÿ MG short length coaches for NMR to be manufactured this year, will be made with SS body and aesthetic interiors for the first time. It will have a suspension tube with taper roller bearings. Under frame Front/ End Part Manufacturing facility of Shop-13 was inaugurated on 12.05.2017 by Shri. E.Natarajan, Tech-I, in the presence of ICF’s team A technical seminar on Electrical Safety measures was of Officers and Staff. conducted on 02.05.2017 at D & D Auditorium. Customer interaction meet of Zonal Railways was held on 12.05.2017 The Renovated Lake View Park was inaugurated on 06.05.2017 by Sri. L.Velu, SSE/16, in the presence of ICF’s team of Officers and Staff. New Badminton court was inaugurated on 08.05.2017 by Shri. -

Tdpc Annual Report 2017-18

Tamil Nadu Technology Development & Promotion Centre ANNUAL REPORT 2017-2018 An Autonomous Society of Confederation of Indian Industry Government of Tamil Nadu Tamil Nadu Technology Development & Promotion Centre Annual Report | 2017-2018 1 Annual Report | 2017-2018 CONTENTS PAGE Chairman's Message 3 TNTDPC Governing Board Members 2017-18 4 Executive Committee 2017-18 5 About TNTDPC 6 Services 6 Focus 8 Activities 9 2 Annual Report | 2017-2018 Chairman's Message MSME sector is acknowledged as the backbone of the modern Indian economy for its crucial role in equitable growth and social inclusion. The merit of the sector lies in its spread in terms of employment potential and improving the standard of living, especially for the marginalized and those living in challenging terrains. To enable the sector to achieve its full potential, the Government has prioritized favorable policies and schemes like Startup India, Make in India, Skill India, and MUDRA loans for the sustainable growth of MSMEs and Indian economy. Technology upgradation and Digital India scheme plays a vital role in the development of MSMEs and also acts as a catalyst to be more competitive in the existing business environment. TNTDPC as one of the technology wings of CII plays a pivotal role between industries, institutes, Government, International partners and many other potential stakeholders to visualize the latest technological dissemination and trends whilst developing a stronger business network. The Centre has been effective in utilizing its networking platforms and consultation to facilitate the knowledge transfer. Activities in the year 2017-18 have come up with potential results in sectors like Agro Food Processing, Automotive, IPR and emerging technologies.