Directory for the Ministry and Life of Priests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seventh Pastoral Letter of Catholic

SEVENTH Pastoral Letter PASTORAL LETTER TO PRIESTS “As the Father hath sent me, even so send I you.” (John 20:21) Feast of the Dormition, 15 August 2004 INTRODUCTION To our beloved sons and brothers, the priests, “Grace, mercy, and peace, from God our Father and Jesus Christ our Lord.” (1 Timothy 1: 2) We greet you with the salutation of the Apostle Paul to his disciple, Timothy, feeling with him that we always have need of the “mercy and peace of God,” just as we always have need of renewal in the understanding of our faith and priesthood, which binds us in a peculiar way to “God our Father and Jesus Christ our Lord.” We renew our faith, so as to become ever more ready to accept our priesthood, and assume our mission in our society. The Rabweh Meeting We held our twelfth annual meeting at Rabweh (Lebanon), from 27 to 31 October 2002, welcomed by our brother H.B. Gregorios III, Patriarch of Antioch, of Alexandria and of Jerusalem for the Melkite Greek Catholics. We studied together the nature of the priesthood, its holiness and everything to do with our priests, confided to our care and dear to our heart. Following on from that meeting, we address this letter to you, dear priests, to express to all celibate and married clergy, our esteem and gratitude for your efforts to make the Word and Love of God present in our Churches and societies. Object of the letter “We thank God at every moment for you,” dear priests, who are working in the vineyard of the Lord in all our eparchies in the Middle East, in the countries of the Gulf and in the distant countries of emigration. -

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

CONGREGATION FOR THE DOCTRINE OF THE FAITH LETTER “IUVENESCIT ECCLESIA” to the Bishops of the Catholic Church Regarding the Relationship Between Hierarchical and Charismatic Gifts in the Life and the Mission of the Church Introduction The gifts of the Holy Spirit in the Church in mission 1. The Church rejuvenates in the power of the Gospel and the Spirit continually renews her, builds her up, and guides her “with hierarchical and charismatic gifts”.[1] The Second Vatican Council has repeatedly highlighted the marvelous work of the Holy Spirit that sanctifies the People of God, guides it, adorns it with virtue, and enrichens it with special graces for her edification. As the Fathers love to show, the action of the divine Paraclete in the Church is multiform. John Chrysostom writes: “What gifts that work for our salvation are not given freely by the Holy Spirit? Through Him we are freed from slavery and called to liberty; we are led to adoption as children and, one might say, formed anew, after having laid down the heavy and hateful burden of our sins. Through the Holy Spirit we see assemblies of priests and we possess ranks of doctors; from this source spring forth gifts of revelation, healing graces, and all of the other charisms that adorn the Church of God”.[2] Thanks to the Church’s life itself, to the numerous Magisterial interventions, and to theological research, happily the awareness has grown of the multiform action of the Holy Spirit in the Church, thus arousing a particular attentiveness to the charismatic gifts by which at all times the People of God are enriched in order to carry out their mission. -

Papal Politics, Paul VI, and Vatican II: the Reassertion of Papal Absolutism Written by Aaron Milavec

Papal Politics, Paul VI, and Vatican II: The Reassertion of Papal Absolutism Written by Aaron Milavec This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Papal Politics, Paul VI, and Vatican II: The Reassertion of Papal Absolutism https://www.e-ir.info/2013/07/28/papal-politics-paul-vi-and-vatican-ii-the-reassertion-of-papal-absolutism/ AARON MILAVEC, JUL 28 2013 During the course of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), free and open discussions gradually took hold among the assembled bishops once the curial grip on the Council was challenged. Within this aggiornamento[1] that was endorsed by John XXIII, the bishops discovered how creative collaboration with each other and with the Holy Spirit served fruitfully to create sixteen documents overwhelmingly approved by the assembled bishops. Given the diversity of viewpoints and the diversity of cultures among the two thousand participants, this consensus building was an extraordinary mark of the charismatic gifts of the movers and shakers at the Council. As Paul VI took over the direction of the Council after the untimely death of John XXIII, he at first endorsed the processes of collegiality that had operated during the initial two years. With the passage of time, however, Paul VI began to use his papal office on multiple levels by way of limiting the competency of the bishops and by way of pushing forward points of view that he and the curia favored. -

Directorio Pastoral De La Iniciación Cristiana Para La Diócesis De Orihuela-Alicante

DIRECTORIO PASTORAL DE LA INICIACIÓN CRISTIANA PARA LA DIÓCESIS DE ORIHUELA-ALICANTE SIGLAS AG = Ad Gentes. Decreto conciliar sobre la actividad misionera de la Iglesia, de 1965. CA = Catequesis de Adultos. Documento de la Comisión Episcopal sobre Catequesis de Adultos, de 1991. CC = Catequesis de la Comunidad. Documento de la Comisión Episcopal sobre catequesis, de 1983. CCE = Catecismo de la Iglesia Católica, 1992. CIC = Código de Derecho Canónico, de 1983 CF = El catequista y su formación. Comisión Episcopal de Enseñanza y Catequesis, de 1985. CT = Catechesi Tradendae. Exhortación Apostólica de Juan Pablo II, de 1976. DGC = Directorio General para la Catequesis. Congregación para el Clero, de 1997. DPF = Directorio de Pastoral Familiar de la Iglesia en España. Conferencia Episcopal Española, de 2003. EE = Ecclesia in Europa Exhortación Apostólica de Juan Pablo II, de 2003 EN = Evangelii Nuntiandi. Exhortación apostólica de Pablo VI, de 1975. FC = Familiaris Consortio. Exhortación Apostólica de Juan Pablo II sobre la Familia de GS = Gaudium et spes. Constitución pastoral sobre la Iglesia en el mundo actual 1965. ICRO = La Iniciación cristiana. Reflexiones y Orientaciones. Conferencia Episcopal Española, de 1998. LG = Lumen Gentium. Constitución conciliar sobre la Iglesia, de 1964. NMI = Novo Millennio Ineunte Carta Apostólica de Juan Pablo II, de 2001. OPC = Orientaciones Pastorales para el Catecumenado. Conferencia Episcopal Española, de 2002. PG = Pastores Gregis. Exhortación apostólica de Juan Pablo II, de 2003 RB = Ritual del Bautismo. RC = Ritual de la Confirmación RICA = Ritual de la Iniciación Cristiana de Adultos, de 1972 RP = Ritual de la Penitencia. 1 INTRODUCCIÓN Motivación del Documento 1. En estos últimos años, un nuevo y vigoroso interés se está despertando en la Iglesia por el tema de la Iniciación cristiana. -

Abuse, Celibacy, Catholic, Church, Priest

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences 2012, 2(4): 88-93 DOI: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120204.03 The Psychology Behind Celibacy Kas o mo Danie l Maseno University in Kenya, Department of Religion Theology and Philosophy Abstract Celibacy began in the early church as an ascetic discipline, rooted partly in a neo-Platonic contempt for the physical world that had nothing to do with the Gospel. The renunciation of sexual expression by men fit nicely with a patriarchal denigration of women. Non virginal women, typified by Eve as the temptress of Adam, were seen as a source of sin. In Scripture: Jesus said to the Pharisees, “And I say to you, whoever divorces his wife, except for unchastity, and marries another commits adultery.” His disciples said to him, “If such is the case of a man with his wife, it is better not to marry.” But he said to them, “Not everyone can accept this teaching, but only those to whom it is given. For there are eunuchs who have been so from birth, there are eunuchs who have been made eunuchs by others, and there are eunuchs who have made themselves eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven. Let anyone accept this who can.” (Matthew 19:3-12).Jesus Advocates for optional celibacy. For nearly 2000 years the Catholic Church has proclaimed Church laws and doctrines intended to more clearly explain the teachings of Christ. But remarkably, while history reveals that Jesus selected only married men to serve as His apostles, the Church today forbids priestly marriage. -

CBCP Monitor A2 Vol

New evangelization Pondo ng ECY @ 25... 25 years must begin with Pinoy @ Seven of youth service A3 the heart, Pope B1 B5 teaches Manila to hold 60-hour adoration for pope’s 60th sacerdotal anniv THE Archdiocese of Manila will hold a 60-hour Eucharistic adoration to mark the 60th anniversary of Pope Benedict XVI’s sacerdotal ordination on June 29. In a communiqué sent to all parish priests, rectors and religious superi- ors throughout the archdiocese, Ma- nila Archbishop Gaudencio Cardinal Rosales said the 60-hour adoration “presents an inspired occasion for us to 00 June 20 - July 3, 2011 Vol. 15 No. 13 Php 20. Sacerdotal / A6 Church soon to implement changes in Mass translation By Pinky Barrientos, FSP CHANGES in the English translation of the Order of the Mass are soon to hit parishes across the country when the full implementation of the new liturgical text is adapted next year. The adoption of the new English translation of the Ro- man Missal has been approved by the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) during its plenary assembly in January this year. Some parts of familiar responses and prayers have been amended to reflect the true meaning in the original Latin text, the language of the Roman liturgy. In the Introductory Rites, for instance, the response of the faithful “And also with you” to the priest’s greeting “The Lord be with you” has been replaced with “And with your spirit.” © Noli Yamsuan / RCAM Yamsuan © Noli Similar changes have also been introduced in other parts of the Mass, such as the Liturgy of the Word, Liturgy of the Eucharist and the Concluding Rites. -

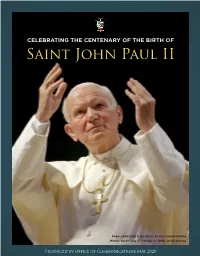

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

The Light from the Southern Cross’

A REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF DIOCESES AND PARISHES IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN AUSTRALIA IMPLEMENTATION ADVISORY GROUP AND THE GOVERNANCE REVIEW PROJECT TEAM REVIEW OF GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF DIOCESES AND PARISHES REPORT – STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL Let us be bold, be it daylight or night for us - The Catholic Church in Australia has been one of the epicentres Fling out the flag of the Southern Cross! of the sex abuse crisis in the global Church. But the Church in Let us be fırm – with our God and our right for us, Australia is also trying to fınd a path through and out of this crisis Under the flag of the Southern Cross! in ways that reflects the needs of the society in which it lives. Flag of the Southern Cross, Henry Lawson, 1887 The Catholic tradition holds that the Holy Spirit guides all into the truth. In its search for the path of truth, the Church in Australia And those who are wise shall shine like the brightness seeks to be guided by the light of the Holy Spirit; a light symbolised of the sky above; and those who turn many to righteousness, by the great Constellation of the Southern Cross. That path and like the stars forever and ever. light offers a comprehensive approach to governance issues raised Daniel, 12:3 by the abuse crisis and the broader need for cultural change. The Southern Cross features heavily in the Dreamtime stories This report outlines, for Australia, a way to discern a synodal that hold much of the cultural tradition of Indigenous Australians path: a new praxis (practice) of church governance. -

I. Werke Von Karol Wojtyła/Papst Johannes Paul II

BIBLIOGRAPHIE I. Werke von Karol Wojtyła/Papst Johannes Paul II. Werke von Karol Wojtyła The Collected Plays and Writings on Theater, übersetzt und eingeleitet von Bolesław Tabor- ski, Berkeley 1987. Discorsi al Popolo di Dio, hrsg. von Flavio Felice, Soveria Mannelli 2006. Der Glaube bei Johannes vom Kreuz. Dissertation an der theologischen Fakultät der Päpstlichen Universität Angelicum in Rom, 1998. I miei amici, Rom 1979. Liebe und Verantwortung. Eine ethische Studie, Freiburg 1979. Metafisica della Persona: Tutte le opere filosofiche e saggi intergrativi, hrsg. von Giovanni Reale und Tadeusz Stycze´n, Mailand 2003. Osoba y czyn: oraz inne studia antropologiczne, hrsg. von Tadeusz Stycze´n, Wojciech Chudy, Jerzy W. Gałkowski, Adam Rodzi´nski und Andrzej Szostek, Lublin 1994. Person and Community: Selected Essays, New York 1993. Person und Tat, Freiburg 1979. Poezje i dramaty, Krakau 1979; rev. Auflage 1998. Poezje · Poems, übersetzt von Jerzy Peterkiewicz, Krakau 1998. Quellen der Erneuerung. Studie zur Verwirklichung des 2. Vatikanischen Konzils, Freiburg 1981. The Way to Christ: Spiritual Exercises, New York 1994. The Word Made Flesh: The Meaning of the Christmas Season, New York 1994. Wykłady lubelskie, hrsg. von Tadeusz Stycze´n, Jerzy W. Gałkowski, Adam Rodzi´nski und Andrzej Szostek, Lublin 1986. Zagadnienie podmiotu moralno´sci, hrsg. von Tadeusz Stycze´n, Jerzy W. Gałkowski, Adam Rodzi´nski und Andrzej Szostek, Lublin 1991. Zeichen des Widerspruchs. Besinnung auf Christus, Freiburg 1979. Werke von Papst Johannes Paul II. Ad Limina Addresses: The Addresses of His Holiness Pope John Paul II to the Bishops of the United States During Their Ad Limina Visits, 5. März – 9. -

Sacerdotalis Caelibatus

SACERDOTALIS CAELIBATUS ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PAUL VI ON THE CELIBACY OF THE PRIEST JUNE 24, 1967 To the Bishops, Priests and Faithful of the Whole Catholic World. Priestly celibacy has been guarded by the Church for centuries as a brilliant jewel, and retains its value undiminished even in our time when the outlook of men and the state of the world have undergone such profound changes. Amid the modern stirrings of opinion, a tendency has also been manifested, and even a desire expressed, to ask the Church to re-examine this characteristic institution. It is said that in the world of our time the observance of celibacy has come to be difficult or even impossible. 2. This state of affairs is troubling consciences, perplexing some priests and young aspirants to the priesthood; it is a cause for alarm in many of the faithful and constrains Us to fulfill the promise We made to the Council Fathers. We told them that it was Our intention to give new luster and strength to priestly celibacy in the world of today. (1) Since saying this We have, over a considerable period of time earnestly implored the enlightenment and assistance of the Holy Spirit and have examined before God opinions and petitions which have come to Us from all over the world, notably from many pastors of God's Church. Some Serious Questions 3. The great question concerning the sacred celibacy of the clergy in the Church has long been before Our mind in its deep seriousness: must that grave, ennobling obligation remain today for those who have the intention of receiving major -

Pastores Dabo Vobis to the Bishops, Clergy and Faithful on the Formation of Priests in the Circumstances of the Present Day

POST-SYNODAL APOSTOLIC EXHORTATION PASTORES DABO VOBIS TO THE BISHOPS, CLERGY AND FAITHFUL ON THE FORMATION OF PRIESTS IN THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE PRESENT DAY INTRODUCTION 1. "I will give you shepherds after my own heart" (Jer. 3:15). In these words from the prophet Jeremiah, God promises his people that he will never leave them without shepherds to gather them together and guide them: "I will set shepherds over them [my sheep] who will care for them, and they shall fear no more, nor be dismayed (Jer. 23.4). The Church, the People of God, constantly experiences the reality of this prophetic message and continues joyfully to thank God for it. She knows that Jesus Christ himself is the living, supreme and definitive fulfillment of God's promise: "I am the good shepherd" (Jn. 10:11). He, "the great shepherd of the sheep" (Heb. 13:20), entrusted to the apostles and their successors the ministry of shepherding God's flock (cf. Jn. 21:15ff.; 1 Pt. 5:2). Without priests the Church would not be able to live that fundamental obedience which is at the very heart of her existence and her mission in history, an obedience in response to the command of Christ: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations" (Mt. 28:19) and "Do this in remembrance of me" (Lk. 22:19; cf. 1 Cor. 11.24), i.e:, an obedience to the command to announce the Gospel and to renew daily the sacrifice of the giving of his body and the shedding of his blood for the life of the world. -

Anuario Argentino De Derecho Canónico, Vol. XI, 2004

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA ARGENTINA SANTA MARÍA DE LOS BUENOS AIRES FACULTAD DE DERECHO CANÓNICO SANTO TORIBIO DE MOGROVEJO ANUARIO ARGENTINO DE DERECHO CANÓNICO Volumen XI 2004 Editado por la Facultad de Derecho Canónico SANTO TORIBIO DE MOGROVEJO de la Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina Santa María de los Buenos Aires Consejo de Redacción Alejandro W. Bunge Director Víctor E. Pinto Ariel D. Busso Nelson Carlos Dellaferrera Con las debidas licencias Queda hecho el depósito que marca la ley 11.723 ISSN: 0328-5049 Editor responsable Editado por la Facultad de Derecho Canónico Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo Dirección y administración Anuario Argentino de Derecho Canónico Av. Alicia Moreau de Justo 1300 C1107AFD Buenos Aires, Argentina Teléfono (54 11) 4349-0451 - Fax (54 11) 4349-0433 Correo electrónico: [email protected] Suscripción ordinaria en el país: $ 30.— Suscripción ordinaria en el exteriror: U$S 20.— ÍNDICE GENERAL COLOQUIO INTERNACIONAL UCA - GREGORIANA, 19-23 DE JULIO 2004 Astigueta, D. G. La persona y sus derechos en las normas sobre los abusos sexuales 11 Bonet Alcón, J. Valor jurídico del amor conyugal 57 Bunge, A. W. La colegialidad episcopal en los pronunciamientos recientes de la Santa Sede. Especial referencia a las Conferencias episcopales . 85 Busso, A. D. El tiempo de nombramiento de los párrocos 109 Ghirlanda, G. Orientaciones para el gobierno de la Diócesis por parte del Obispo según la exhortación apostólica Pastores gregis y el nuevo directorio para el ministerio de los obispos Apostolorum Successores . 129 ARTÍCULOS Baccioli, C. Puntos fundamentales de la pericia psicológico-psiquiátrica en el proceso de nulidad matrimonial 185 Navarro Floria, J.