The Swing Riots 1830 Stirring Times in & Around Elham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flash Flood History Southeast and Coast Date and Sources

Flash flood history Southeast and coast Hydrometric Rivers Tributaries Towns and Cities area 40 Cray Darent Medway Eden, Teise, Beult, Bourne Stour Gt Stour, Little Stour Rother Dudwell 41 Cuckmere Ouse Berern Stream, Uck, Shell Brook Adur Rother Arun, Kird, Lod Lavant Ems 42 Meon, Hamble Itchen Arle Test Dever, Anton, Wallop Brook, Blackwater Lymington 101 Median Yar Date and Rainfall Description sources Sept 1271 <Canterbury>: A violent rain fell suddenly on Canterbury so that the greater part of the city was suddenly Doe (2016) inundated and there was such swelling of the water that the crypt of the church and the cloisters of the (Hamilton monastery were filled with water’. ‘Trees and hedges were overthrown whereby to proceed was not possible 1848-49) either to men or horses and many were imperilled by the force of waters flowing in the streets and in the houses of citizens’. 20 May 1739 <Cobham>, Surrey: The greatest storm of thunder rain and hail ever known with hail larger than the biggest Derby marbles. Incredible damage done. Mercury 8 Aug 1877 3 Jun 1747 <Midhurst> Sussex: In a thunderstorm a bridge on the <<Arun>> was carried away. Water was several feet deep Gentlemans in the church and churchyard. Sheep were drowned and two men were killed by lightning. Mag 12 Jun 1748 <Addington Place> Surrey: A thunderstorm with hail affected Surrey (and <Chelmsford> Essex and Warwick). Gentlemans Hail was 7 inches in circumference. Great damage was done to windows and gardens. Mag 10 Jun 1750 <Sittingbourne>, Kent: Thunderstorm killed 17 sheep in one place and several others. -

Letter C Introduction This Index Covers Volumes 110–112 and 114–120 Inclusive (1992–2000) of Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 113 Being the Preceding General Index

Archaeologia Cantiana - On-line Index 2012 GENERAL INDEX TO VOLUMES CX 1992 ( 110 ) to CXX 2000 ( 120 ) Letter C Introduction This index covers volumes 110–112 and 114–120 inclusive (1992–2000) of Archaeologia Cantiana, volume 113 being the preceding General Index. It includes all significant persons, places and subjects with the exception of books reviewed. Volume numbers are shown in bold type and illustrations are denoted by page numbers in italic type or by (illus.) where figures occur throughout the text. The letter n after a page number indicates that the reference will be found in a footnote and pull-out pages are referred to as f – facing. Alphabetisation is word by word. Women are indexed by their maiden name, where known, with cross references from any married name(s). All places within historic Kent are included and are arranged by civil parish. Places that fall within Greater London are to be found listed under their London Borough. Places outside Kent that play a significant part in the text are followed by their post 1974 county. Place names with two elements (e.g. East Peckham, Upper Hardres) will be found indexed under their full place name. T. G. LAWSON, Honorary Editor Kent Archaeological Society, February 2012 Abbreviations m. married Ald. Alderman E. Sussex East Sussex M.P. Member of Parliament b. born ed./eds. editor/editors Notts. Nottinghamshire B. & N.E.S. Bath and North East f facing Oxon. Oxfordshire Somerset fl. floruit P.M. Prime Minister Berks. Berkshire G. London Greater London Pembs. Pembrokeshire Bt. Baronet Gen. General Revd Reverend Bucks. -

Coast Path Makes Progress in Essex and Kent

walkerSOUTH EAST No. 99 September 2017 Coast path makes progress in Essex and Kent rogress on developing coast path in Kent with a number the England Coast Path of potentially contentious issues Pnational trail in Essex and to be addressed, especially around Kent has continued with Natural Faversham. If necessary, Ian England conducting further will attend any public hearings route consultations this summer. Ramblers volunteers have been or inquiries to defend the route very involved with the project proposed by Natural England. from the beginning, surveying Consultation on this section closed routes and providing input to on 16 August. proposals. The trail, scheduled Meanwhile I have started work to be completed in 2020, will run on the second part of the Area's for about 2,795 miles/4.500km. guide to the Kent Coast Path which is planned to cover the route from Kent Ramsgate to Gravesend (or possibly It is now over a year since the section of the England Coast Path further upriver). I've got as far as from Camber to Ramsgate opened Reculver, site of both a Roman fort in July 2016. Since then work has and the remains of a 12th century been underway to extend the route church whose twin towers have long in an anti-clockwise direction. been a landmark for shipping. On The route of the next section from the way I have passed delightful Ramsgate to Whitstable has been beaches and limestone coves as well determined by the Secretary of as sea stacks at Botany Bay and the State but the signage and the works Turner Contemporary art gallery at necessary to create a new path along Margate. -

A Guide to Parish Registers the Kent History and Library Centre

A Guide to Parish Registers The Kent History and Library Centre Introduction This handlist includes details of original parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts held at the Kent History and Library Centre and Canterbury Cathedral Archives. There is also a guide to the location of the original registers held at Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre and four other repositories holding registers for parishes that were formerly in Kent. This Guide lists parish names in alphabetical order and indicates where parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts are held. Parish Registers The guide gives details of the christening, marriage and burial registers received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish catalogues in the search room and community history area. The majority of these registers are available to view on microfilm. Many of the parish registers for the Canterbury diocese are now available on www.findmypast.co.uk access to which is free in all Kent libraries. Bishops’ Transcripts This Guide gives details of the Bishops’ Transcripts received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish handlist in the search room and Community History area. The Bishops Transcripts for both Rochester and Canterbury diocese are held at the Kent History and Library Centre. Transcripts There is a separate guide to the transcripts available at the Kent History and Library Centre. These are mainly modern copies of register entries that have been donated to the -

North Downs East North Downs East

Cheriton Shepway Ward Profile May 2015 North Downs East North Downs East -2- North Downs East Brief introduction to area ..............................................................................4 Map of area ......................................................................................................5 Demographic ...................................................................................................6 Local economy ................................................................................................9 Transport .......................................................................................................13 Education and skills .................................................................................... 14 Health & wellbeing .......................................................................................16 Housing ..........................................................................................................21 Neighbourhood/community ......................................................................23 Planning & Development ...........................................................................24 Physical Assets .............................................................................................25 Arts and culture .......................................................................................... 29 Crime ........................................................................................................... 30 Endnotes/websites .......................................................................................31 -

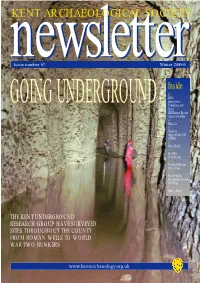

K E N T a Rc H a E O Lo G I C a L S O C I E

KE N T ARC H A E O LO G I C A L SO C I E T Y nnIssue numberee 67 wwss ll ee tt tt ee Winter r2005/6r Inside 2-3 KURG Library Notes GOING UNDERGROUND Tebbutt Research Grants KHBCRequire Recruits Letters to the Editor 4-5 What’s on 6-7 What’s on Happy Birthday CAT CATKITS 8-9 Notice Board 10-11 Bee Boles Cattle Droving 12-13 Wye Rural Museum YACActivities 14-15 Thanet Pipeline Microfilm Med Records New Books 16 Hunt the Saxons THE KENT UNDERGROUND RESEARCH GROUP HAVE SURVEYED SITES THROUGHOUT THE COUNTY FROM ROMAN WELLS TO WORLD WAR TWO BUNKERS www.kentarchaeology.org.uk KE N T UN D E R G R O U N D RE S E A R C H GR O U P URG is an affiliated group of the KAS. We are mining historians – a unique blend of unlikely Kopposites. We are primarily archaeologists and carry out academic research into the history of underground features and associated industries. To do this, however, we must be practical and thus have the expertise to carry out exploration and sur- veying of disused mines. Such places are often more dangerous than natural caverns, but our members have many years experience of such exploration. Unlike other mining areas, the South East has few readily available records of the mines. Such records as do exist are often found in the most unlikely places and the tracing of archival sources is an ongoing operation. A record of mining sites is maintained and constantly updated as further sites are discovered. -

South East Water Licence

South East – Water Undertaker - Appointment Instrument of Appointment for South East Water Limited March 2021 Consolidated working copies of Appointments are not formal documents and for some purposes you may need to consider the formal appointments and variations to appointments rather than this consolidated working copy. A list of all variations made to these appointments is contained in a consolidation note at the back of this working copy. South East – Water Undertaker - Appointment TABLE OF CONTENTS Appointment of Mid-Sussex Water plc [South East Water Limited] as Water Undertaker in place of South East Water Ltd and Mid Southern Water plc ..................................................... 2 Schedule 1: Area for which the Appointment is made .............................................................. 4 Schedule 2: Conditions of the Appointment ............................................................................ 25 Condition A: Interpretation and Construction ........................................................ 25 Condition B: Charges .............................................................................................. 34 Condition C: Infrastructure Charges ....................................................................... 73 Condition D: New connections ............................................................................... 84 Condition E: Undue Preference/Discrimination in Charges ................................... 85 Condition E1: Prohibition on undue discrimination and undue preference and -

Minutes 21St November 2017

WOMENSWOLD PARISH COUNCIL A Meeting of Womenswold Parish Council was held at the Learning Opportunities Centre, Womenswold on Tuesday 21st November 2017 at 7.00pm Present: Cllr I HOBSON – Chairman Cllr M McKENZIE -Vice Chair Cllr A WICKEN Cllr C BROWN Cllr J PERRINS Mrs V McWILLIAMS Clerk There were no members of the public present. The Chairman welcomed everyone to the meeting. 1 Apologies for Absence Michael Northey sent his apologies due a prior engagement 2. Comments from the public. None 3. Declaration of interests by Councillors. There was no notification by members given of any pecuniary or personal interest in items on the Agenda. 4. Reports from County Cllr Northey & City Cllr Cook City Cllr Simon Cook attended the meeting and reported that: The City Council will be putting next year's budget out for consultation next week – they have again managed to keep it balanced, whilst preserving frontline services. He had had a meeting with Chief Inspector Weller (the District Commander) last week and he has agreed to keep a close eye on the illegal lorry parking on the Cold Harbour Lane /A2 slip road. Finally, the City Council web page for reporting fly tipping has been improved and can now be used to upload photos and the location can be pinpointed from a map or a phone location, rather than having to be described; everyone is urged to use it if they see any fly tipped rubbish. He reported that the Christmas Hampers from the Lord Mayor of Canterbury’s Christmas Gift Fund were now ready for distribution and he would be delivering them next week County Cllr Michael Northey was unable to attend the meeting but sent the following: The Winter Service is now in operation. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Charles Oxenden

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society CHARLES OXENDEN Cricketer, Cleric and Medical Pioneer PHILIP H. BLAKE St. Patrick's Day, 1979, was the 105th anniversary of the death of the Rev. Charles Oxenden, Hon. Canon of Canterbury and first rector of the separate living of Barham, near Canterbury — and the fact will mean practically nothing to most people. Yet, a great national institution, the Eton v. Harrow cricket match, played annually at Lord's for over 150 years, was his foundation, and as a pioneer in the administration of health services for the poor he was advocating to a Parliamentary Committee 125 years ago that free medical attention should be provided on a national basis to every- one below a certain income. At that time, also, he was managing a medical provident society of over 2,000 members that he himself had founded 20 years previously. But past is all his fame. The very spot, Where many a time he triumph'd, is forgot. It is the object of this paper to recall some of the details of this useful life. Charles Oxenden was the fourth son of Sir Henry Oxenden, 7th baronet, of Broome House in Barham, where he was born on 23rd May, 1800, baptized privately three days later and was received into the Church at Barham on 25th July following. He went to school first at Eton, but was later transferred to Harrow. Although there is now no record of the exact dates of his entering and leaving either school, he certainly entered Eton in 1814 after Election, i.e., after late July, when candidates were chosen King's Scholars, and probably, therefore, at the beginning of the autumn term. -

Local Footpath Officer Vacancies at 3 May 2021

Kent Ramblers: Local Footpath Officer Vacancies at T 3 May 2021 h a m e E r e a e s s m d t e e v a l d e B es Lesn ey Abb Erith St. C All orthumberland N o Mary s Hallows ' o l Heath North e l Hoo . i n t a End Cliffe g ast S h Brampton E c i and ham k M ic t Cl W s iffe r W u oods h Stoke Isle h e Hig Danson e b n om alstow of P r rd c H ark a o ns B f a d e Grain y w n h ra Stone S a it C nh n e y B e e lend r e o f n G d b Dartford k Sh r and ee c n rne o s a a t. s l Pen S E m hil b B l bsf m a Mary's leet ha L g Hi o o . h up Gravesend H t rg Halfway L Sidc S u o rb Houses W n e g a la gton B W r n ilmin Da ean d d Cra W S r s y en h e u th y g ur u n Meadows t sb t nd o o Fri a r n r o H t Ext b M a - flee a South n in n a w e s a t e d Shorne t Margate - e e l u e H r Q - Eastchurch S y o table o n - x n He n -S e e o L a - Br o e oa ngf t d ie d a s Ho ld o a tai S an o g n rs w rto d tr Birchington t d a s nl Ki n N S S ey rb ew e t. -

COUNTRYSIDE Page 1 of 16

Page 1 of 16 COUNTRYSIDE Introduction 12.1 Shepway has a rich and diverse landscape ranging from the rolling chalk downland and dry valleys of the North Downs, through the scarp and dip slope of the Old Romney Shoreline, to Romney Marsh and the unique shingle feature of the Dungeness peninsula. This diversity is reflected in the range of Natural Areas and Countryside Character Areas, identified by English Nature and the Countryside Agency respectively, which cover the District. The particular landscape and wildlife value of large parts of the District is also recognised through protective countryside designations, including Sites of Special Scientific Interest and Heritage Coastline, as well as the Kent Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The countryside also plays host to a wide range of activities and it is recognised that the health of the rural economy and the health of the countryside are inter-linked. A function of the Local Plan is to achieve a sustainable pattern of development in the countryside. This involves a balance between the needs of rural land users and maintaining and enhancing countryside character and quality. 12.2 This balance is achieved in two main ways:- a. By focussing most development in urban areas, particularly on previously developed sites and ensuring that sufficient land is allocated to meet identified development requirements, thus reducing uncertainty and speculation on ‘greenfield’ sites in the countryside. b. By making firm policy statements relating to: the general principles to be applied to all proposals in the countryside; specific types of development in the countryside; and the protection of particularly important areas.