Early M Finland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scaramouche and the Commedia Dell'arte

Scaramouche Sibelius’s horror story Eija Kurki © Finnish National Opera and Ballet archives / Tenhovaara Scaramouche. Ballet in 3 scenes; libr. Paul [!] Knudsen; mus. Sibelius; ch. Emilie Walbom. Prod. 12 May 1922, Royal Dan. B., CopenhaGen. The b. tells of a demonic fiddler who seduces an aristocratic lady; afterwards she sees no alternative to killinG him, but she is so haunted by his melody that she dances herself to death. Sibelius composed this, his only b. score, in 1913. Later versions by Lemanis in Riga (1936), R. HiGhtower for de Cuevas B. (1951), and Irja Koskkinen [!] in Helsinki (1955). This is the description of Sibelius’s Scaramouche, Op. 71, in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet. Initially, however, Sibelius’s Scaramouche was not a ballet but a pantomime. It was completed in 1913, to a Danish text of the same name by Poul Knudsen, with the subtitle ‘Tragic Pantomime’. The title of the work refers to Italian theatre, to the commedia dell’arte Scaramuccia character. Although the title of the work is Scaramouche, its main character is the female dancing role Blondelaine. After Scaramouche was completed, it was then more or less forgotten until it was published five years later, whereupon plans for a performance were constantly being made until it was eventually premièred in 1922. Performances of Scaramouche have 1 attracted little attention, and also Sibelius’s music has remained unknown. It did not become more widely known until the 1990s, when the first full-length recording of this remarkable composition – lasting more than an hour – appeared. Previous research There is very little previous research on Sibelius’s Scaramouche. -

Ikkunoita Inkerin Elämään Muistoissa Musiikkiliikunnan Uranuurtaja Inkeri Simola-Isaksson

Ikkunoita Inkerin elämään Muistoissa musiikkiliikunnan uranuurtaja Inkeri Simola-Isaksson Ikkunoita Inkerin elämään Muistoissa musiikkiliikunnan uranuurtaja Inkeri Simola-Isaksson Juntunen, M.-L., Aarnio, H.-M. & Perkiö, S. (toim.) Taideyliopiston Sibelius-Akatemia 2015 Sibelius-Akatemian julkaisuja 14 Kustannustoimittaja: Päivi Kerola-Innala Taitto: Henri Terho Kansi: Tiina Laino Etukannen kuva: Juuso Kauppinen Takakannen kuva: Ritva Mannerin kotiarkisto Kustantaja: Taideyliopiston Sibelius-Akatemia Paino ja painopaikka: Vammalan Kirjapaino Oy, Helsinki 2015 ISSN 0359-2308 ISBN 978-952-329-021-1 (painettu) ISBN 978-952-329-022-8 (pdf) Sisällys Lukijalle ........................................................................................................ 7 Lapsuus ja nuoruus ...................................................................................... 13 Juureni ovat vahvasti Pohjanmaalla ................................................. 13 Minulla oli hirveä halu soittamiseen ................................................. 15 Minä soitin ja toiset tanssi ............................................................... 22 Lukioaika turvallisessa körttiläisilmapiirissä Lapualla ....................... 23 Ylioppilaana kansakoulunopettajaksi Teuvalle .................................. 25 Voimistelulaitoksen pääsykokeista Sibelius-Akatemiaan ................ 27 Opinnot Sibelius-Akatemiassa ja Helsingin opettajakorkeakoulussa .......... 30 Laulunopettajaksi Sibelius-Akatemiassa 1950–53 ........................... 30 Kansakoulunopettajaksi -

Mannerheim Library A-Ö

Mannerheim library A-Ö Historical Historical Author(s) Imprint notes Title A list of books on the fine and applied arts. Autumn 1923. A list of London : Benn, 1923 A. Ahlström Osakeyhtiö. A. Ahlström Beslut och order. 1, Taktiska uppgifter I-II. II. A. v M. Arméfördelningen under förläggning, marsch och strid. / Matérn, Axel Fredrik Signed by G. bearb. af A v. M. von, 1848-1920 Stockholm : Norstedt, Mannerheim. Helsinki : Suomen Länsi-Suomen yhteismyllyt : yhteiskuntahistoriallinen Aaltonen, Esko, muinaismuistoyhdistys tutkimus / Esko Aaltonen. 1893-1966. Author. , 1944. Pages not opened Aarne, Uuno V., 1890-1985. Editor. Viherjuuri, Leonard Maurits,1885 - 1957. Kultasepän käsikirja / toimittaneet Uuno V. Aarne, L. M. Editor. Helsinki: Suomen Viherjuuri ; avustajina Aarno Aho ...[et al.] ; toimikunta: Aho, Aarno. kultaseppien liitto, Lauri Viljanen ...[et al.]. Collaborator. 1945. Feltmarsalk Mannerheim. 1933. Aavatsmark, Fanny The Abdals in eastern Turkestan from an anthropological point of view. London 1949 Abdals... About, Edmond, 1828-1885. Author. Les mariages de Paris / par Edmond About ; introduction Faguet, Émile, 1847- par Émile Faguet. 1916. Preface. Paris : Nelson, [19--?]. Abrantès, Laure Junot, Duchesse d', 1830 mémoires de la Duchesse d'Abrantès / la Duchesse 1784-1838. Author. d'Abrantès; publiés avec une introduction par Louis - Loviot, Louis. Paris : A. Fayard, Loviot. Editor. [1910]. Ex libris. Dedicated to mannehriem by Generaloberst und Obersbefelshaber der 18. armee. Abschnitt Lenningrad Abschnitt 1/11/1943. Acht Hengste aus der k.k. spanischen Hofreitschule in Wien : dargestellt in den Gangarten der hohen Schule : acht photographischen Drucke Acht… Wien ; Hölgl., [1883] Half title: Dedication: “Till Fältmarskalken, Baron G. Mannerheim med högaktning och tacksamhet. AinoAckté- Jalander.” Letter of dedication by Aino Ackté- Ackté-Jalander, Helsinki ; Otava ; Jalander inside Taiteeni taipaleelta Aino. -

Latvialaiset Suomessa

Marjo Mela & Markku Mattila Marjo Mela & Markku Marjo Mela & Markku Mattila Marjo Mela & Markku Mattila LATVIALAISET SUOMESSA Nyky-Suomen ja Latvian alueet ovat hyvin pitkään olleet koske- LATVIALAISET tuksissa toistensa kanssa. Kosketus on aikojen saatossa voimak- SUOMESSA LATVIALAISET kuudeltaan vaihdellut, mutta se ei ole koskaan tyystin katkennut. Ollessaan nyt Euroopan unionissa molemmat kansakunnat ovat SUOMESSA taas osa yhtä suurempaa poliittista kokonaisuutta, kuten asia oli myös Ruotsin suurvaltakaudella ja Suomen autonomisen suuri- ruhtinaskunnan aikana. Nykyisellään Suomessa asuu noin pari tuhatta latvialaista. Kirja jakaantuu kahteen osaan. Osassa I luodaan yleiskuva Suo- men ja Latvian suhteisiin halki aikojen. Osa II käsittelee Suomessa asuneiden latvialaisten historiaa pieninä tarinoina ennen kaikkea henkilökuvien kautta. Teos valottaa latvialaisia ja latvialaisuutta Suomessa kahdella tasolla: suurten tapahtumien ylätasolla ja toi- saalta yksityisten ihmisten kokemuksen ja elämäntarinoiden ta- solla. ISBN 978-952-7167-71-7 (nid.) ISBN 978-952-7167-72-4 (pdf) ISSN 2343-3507 (painettu) ISSN 2343-3515 (verkkojulkaisu) 25 JULKAISUJA 25 www.migrationinstitute.fi Latvialaiset Suomessa Marjo Mela & Markku Mattila Turku 2019 Kansikuva: Johan Rosenberg ämpärin ja lapion kanssa tutustumassa kevääseen. Kuva: Thomas Rosenbergin kokoelma. Julkaisuja 25, 2019 Siirtolaisuusinstituutti Copyright © Siirtolaisuusinstituutti & kirjoittajat ISBN 978-952-7167-71-7 (nid.) ISBN 978-952-7167-72-4 (pdf) ISSN 2343-3507 (painettu) ISSN 2343-3515 -

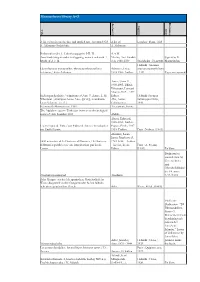

213 a Chronological List of Written Histories of Finnish Dance. Appendix 1

213 A chronological list of written histories of Finnish dance. Appendix 1 Title and focus Type of publication References af Hällström, R. (1929b) Alina Frasan valkea liina. Suomen Kuvalehti 14/1929, 623-624. article - the past of dance in Finland af Hällström, R. (1932)Tanssitaidetta Suomessa. Nuori Suomi 1932, 199- 217. article - ballet and modern dance in Finland Havukka, U. (1932) Suomalaisen Oopperan baletti . Naamio 1/1932, 5-8. - the Finnish National Ballet article Björkenheim, M. (1938) Den klassiska konstdansen . Helsingfors: Söderstrom & Co. book X - aesthetic of classical dance art, no mention on Finnish dance af Hällström, R. (1945a) Siivekkäät jalat . Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Kivni. book - history of ballet and modern dance af Hällström, R. (1945b) Siivekkäät jalat . Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Kivi, revised edition. (three more articles) book Havukka, U. (1945) Danskonsten i Finland . An unpublished manuscript for Bengt Häger before the choreography competition in Stockholm in 1945. manuscript, unpublished - outlines of Finnish dance art af Hällström, R. (1947) Kansallisen tulevaisuus. An unknown publication 1947 (TeaMA 1152), 111-118. article - future of the Finnish National Ballet Gripenberg, M. (1950) Rytmin lumoissa . Helsinki: Otava. - Finnish pioneer of modern dance Maggie Gripenberg’s life autobiography/book Walto, E. (1962) Kansallisen balettimme syntyvaiheita I & II. Ilta Sanomat 6 & 12/1962. article - 40th anniversary of the Finnish National Ballet af Hällström, R. (1972) Balettimme viisi vuosikymmentä. Ensimmäinen Joutsenlampi oli suurenmoista juhlaa. Helsingin Sanomat 16.1. 1972. article - 50th anniversary of the Finnish National Ballet Hämäläinen, S. (1980) Vapaa tanssi, moderni tanssi ja naisvoimistelu – kehitys ja sisällölliset yhtymäkohdat . Unpublished MA dissertation, University of Jyväskylä. MA dissertation X - development of free dance, modern dance and women’s gymnastics Vienola-Lindfors, I. -

Volume 4 (2), 2013 Contents Editorial

– practice, education and research Volume 4 (2), 2013 Contents Editorial Editorial .....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Dance is a diverse cultural phenomenon. experience and the works by the Swedish Traditional forms continue their existence, choreographer Per Jonsson, and especially on Practical Papers: Joey Chua and Hannele Niiranen: ’Ballet Energy for Boys’ in Finland: migrate and merge with new forms. Some forms how traditions are reenacted by dance revival A Description of the Workshop Content ....................................................................................................................................................................................................4 are widely known, recognized and practiced, and reconstruction. some are familiar mostly to communities The issue includes two peer-reviewed Cecilia Roos: Embodied Timing − Passing Time ....................................................................................................................................................................12 practicing or researching them. Nordic Journal research articles. In her contribution, Johanna Research Papers: of Dance: Practice, Education and Research Laakkonen explores the interplay between Johanna Laakkonen: Early Modern Dance and Theatre in Finland ...............................................................................................................18