Journal Vol. LX. No. 2. 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Abbreviations of the Names of Languages in the Statistical Maps

V Contents Abbreviations of the names of languages in the statistical maps. xiii Abbreviations in the text. xv Foreword 17 1. Introduction: the objectives 19 2. On the theoretical framework of research 23 2.1 On language typology and areal linguistics 23 2.1.1 On the history of language typology 24 2.1.2 On the modern language typology ' 27 2.2 Methodological principles 33 2.2.1 On statistical methods in linguistics 34 2.2.2 The variables 41 2.2.2.1 On the phonological systems of languages 41 2.2.2.2 Techniques in word-formation 43 2.2.2.3 Lexical categories 44 2.2.2.4 Categories in nominal inflection 45 2.2.2.5 Inflection of verbs 47 2.2.2.5.1 Verbal categories 48 2.2.2.5.2 Non-finite verb forms 50 2.2.2.6 Syntactic and morphosyntactic organization 52 2.2.2.6.1 The order in and between the main syntactic constituents 53 2.2.2.6.2 Agreement 54 2.2.2.6.3 Coordination and subordination 55 2.2.2.6.4 Copula 56 2.2.2.6.5 Relative clauses 56 2.2.2.7 Semantics and pragmatics 57 2.2.2.7.1 Negation 58 2.2.2.7.2 Definiteness 59 2.2.2.7.3 Thematic structure of sentences 59 3. On the typology of languages spoken in Europe and North and 61 Central Asia 3.1 The Indo-European languages 61 3.1.1 Indo-Iranian languages 63 3.1.1.1New Indo-Aryan languages 63 3.1.1.1.1 Romany 63 3.1.2 Iranian languages 65 3.1.2.1 South-West Iranian languages 65 3.1.2.1.1 Tajiki 65 3.1.2.2 North-West Iranian languages 68 3.1.2.2.1 Kurdish 68 3.1.2.2.2 Northern Talysh 70 3.1.2.3 South-East Iranian languages 72 3.1.2.3.1 Pashto 72 3.1.2.4 North-East Iranian languages 74 3.1.2.4.1 -

Journal Vol. LX. No. 2. 2018

JOURNAL OF THE ASIATIC SOCIETY VOLUME LX No. 4 2018 THE ASIATIC SOCIETY 1 PARK STREET KOLKATA © The Asiatic Society ISSN 0368-3308 Edited and published by Dr. Satyabrata Chakrabarti General Secretary The Asiatic Society 1 Park Street Kolkata 700 016 Published in February 2019 Printed at Desktop Printers 3A, Garstin Place, 4th Floor Kolkata 700 001 Price : 400 (Complete vol. of four nos.) CONTENTS ARTICLES The East Asian Linguistic Phylum : A Reconstruction Based on Language and Genes George v an Driem ... ... 1 Situating Buddhism in Mithila Region : Presence or Absence ? Nisha Thakur ... ... 39 Another Inscribed Image Dated in the Reign of Vigrahapäla III Rajat Sanyal ... ... 63 A Scottish Watchmaker — Educationist and Bengal Renaissance Saptarshi Mallick ... ... 79 GLEANINGS FROM THE PAST Notes on Charaka Sanhitá Dr. Mahendra Lal Sircar ... ... 97 Review on Dr. Mahendra Lal Sircar’s studies on Äyurveda Anjalika Mukhopadhyay ... ... 101 BOOK REVIEW Coin Hoards of the Bengal Sultans 1205-1576 AD from West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Assam and Bangladesh by Sutapa Sinha Danish Moin ... ... 107 THE EAST ASIAN LINGUISTIC PHYLUM : A RECONSTRUCTION BASED ON LANGUAGE AND GENES GEORGE VAN DRIEM 1. Trans-Himalayan Mandarin, Cantonese, Hakka, Xiâng, Hokkien, Teochew, Pínghuà, Gàn, Jìn, Wú and a number of other languages and dialects together comprise the Sinitic branch of the Trans-Himalayan language family. These languages all collectively descend from a prehistorical Sinitic language, the earliest reconstructible form of which was called Archaic Chinese by Bernard Karlgren and is currently referred to in the anglophone literature as Old Chinese. Today, Sinitic linguistic diversity is under threat by the advance of Mandarin as a standard language throughout China because Mandarin is gradually taking over domains of language use that were originally conducted primarily in the local Sinitic languages. -

Grammaticalization Processes in the Languages of South Asia

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Grammaticalization processes in the languages of South Asia Coupe, Alexander R. 2018 Coupe, A. R. (2018). Grammaticalization processes in the languages of South Asia. In H. Narrog, & B. Heine (Eds.), Grammaticalization from a Typological Perspective (pp. 189‑218). doi:10.1093/oso/9780198795841.003.0010 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/146316 https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198795841.003.0010 © 2018 Alexander R. Coupe. First published 2018 by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Downloaded on 28 Sep 2021 13:23:43 SGT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 22/9/2018, SPi 10 Grammaticalization processes in the languages of South Asia ALEXANDER R. COUPE . INTRODUCTION This chapter addresses some patterns of grammaticalization in a broad selection of languages of South Asia, a region of considerable cultural and linguistic diversity inhabited by approximately . billion people living in eight countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Maldives, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) and speaking known languages (Simons and Fennig ). The primary purpose of the chapter is to present representative examples of grammaticalization in the languages of the region—a task that also offers the opportunity to discuss correlations between the South Asian linguistic area and evidence suggestive of contact-induced grammat- icalization. With this secondary objective in mind, the chapter intentionally focuses upon processes that either target semantically equivalent lexical roots and construc- tions or replicate syntactic structures across genetically unrelated languages. The theoretical concept of ‘grammaticalization’ adopted here is consistent with descriptions of the phenomenon first proposed by Meillet (), and subsequently developed by e.g. -

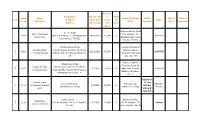

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. Name Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Application Pay in of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Pay Flat Band Accounts Officer, 9D & Gr. - II Sister Smt. Anita Biswas B.G. Hospital , 57, 1 1879 9D & B.G. Hospital , 57, Beleghata Main 28/12/2012 21,140 A ALLOTTED Sri Salil Dey Beleghata Main Road, Road, Kolkata - 700 010 Kolkata - 700 010 District Fishery Officer Assistant Director of Bikash Mandal O/O the Deputy Director of Fisheries, Fisheries, Kolkata 2 1891 31/12/2012 22,500 A ALLOTTED Lt. Joydev Mandal Kolkata Zone, 9A, Esplanade East, Kol - Zone, 9A, Esplanade 69 East , Kol - 69 Asstt. Director of Fishery Extn. Officer Fisheries, South 24 Swapan Kr. Saha O/O The Asstt. Director of Fisheries 3 1907 1/1/2013 17,020 A Pgns. New Treasury ALLOTTED Lt. Basanta Saha South 24 Pgs., Alipore, New Treasury Building (6th Floor), Building (6th Floor), Kol - 27 Kol - 27 Eligible for Samapti Garai 'A' Type Assistant Professor Principal, Lady Allotted '' 4 1915 Sri Narayan Chandra 2/1/2013 20,970 A flats but Lady Brabourne College Brabourne College B'' Type Garai willing 'B' Type Flat Staff Nurse Gr. - II Accounts Officer, Lipika Saha 5 1930 S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, A.J.C. Bose Rd. , 4/1/2013 16,380 A S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, Allotted Sanjit Kumar Saha Kol -20 A.J.C. Bose Rd. , Kol -20 Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. -

Journal of South Asian Linguistics

Volume 8, Issue 1 July 2018 Journal of South Asian Linguistics Volume 8 Published by CSLI Publications Contents 1 Review of The Languages and Linguistics of South Asia: A Contemporary Guide 3 Farhat Jabeen 1 JSAL volume 8, issue 1 July 2018 Review of The Languages and Linguistics of South Asia: A Contemporary Guide Farhat Jabeen, University of Konstanz Received December 2018; Revised January 2019 Bibliographic Information: The Languages and Linguistics of South Asia: A Contemporary Guide. Edited by Hans Heinrich Hock and Elena Bashir. De Gruyter Mouton. 2016. 1 Introduction With its amazing linguistic diversity and the language contact situation caused by centuries of mi- gration, invasion, and cultural incorporation, South Asia offers an excellent opportunity for linguists to exercise their skill and challenge established theoretical linguistic claims. South Asian languages, with their unique array of linguistic features, have offered interesting challenges to prevalent formal linguistic theories and emphasized the need to expand their horizons and modify their theoretical assumptions. This book is the 7th volume of The World of Linguistics series edited by Hans Heinrich Hock. The current book is jointly edited by Hans Heinrich Hock and Elena Bashir, two excellent South Asian linguists with extensive experience of working in the field on a number of South Asian languages. At more than 900 pages, the volume is divided into ten sections pertaining to different linguistic levels (morphology, phonetics and phonology, syntax and semantics), grammatical traditions to study South Asian languages, sociological phenomena (contact and convergence) and sociolinguistics of South Asia, writing systems, as well as the use of computational linguistics approach to study South Asian languages in the twentieth century. -

Drastic Demographic Events Triggered the Uralic Spread to Appear in Diachronica

Drastic demographic events triggered the Uralic spread To appear in Diachronica Riho Grünthal (University of Helsinki) Volker Heyd (University of Helsinki) Sampsa Holopainen (University of Helsinki) Juha Janhunen (University of Helsinki) Olesya Khanina (Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences) Matti Miestamo (University of Helsinki) Johanna Nichols (University of California, Berkeley; University of Helsinki; Higher School of Economics, Moscow) Janne Saarikivi (University of Helsinki) Kaius Sinnemäki (University of Helsinki) Abstract: The widespread Uralic family offers several advantages for tracing prehistory: a firm absolute chronological anchor point in an ancient contact episode with well-dated Indo-Iranian; other points of intersection or diagnostic non-intersection with early Indo-European (the Late PIE-speaking Yamnaya culture of the western steppe, the Afanasievo culture of the upper Yenisei, and the Fatyanovo culture of the middle Volga); lexical and morphological reconstruction sufficient to establish critical absences of sharings and contacts. We add information on climate, linguistic geography, typology, and cognate frequency distributions to reconstruct the Uralic origin and spread. We argue that the Uralic homeland was east of the Urals and initially out of contact with Indo-European. The spread was rapid and without widespread shared substratal effects. We reconstruct its cause as the interconnected reactions of early Uralic and Indo-European populations to a catastrophic climate change episode and interregionalization opportunities which advantaged riverine hunter-fishers over herders. Keywords Uralic; Finno-Ugric; Indo-European; Yamnaya; Indo-Iranian; Siberia; Eurasia; Seima-Turbino, 4.2 ka event; linguistic homeland Note: In-text references have not yet been fully deanonymized. 2 Drastic demographic events triggered the Uralic spread (Contents, for convenience) Main text (pp. -

Classes Lexicais E Gramaticalização: Adjetivos Em Línguas Geneticamente Não Relacionadas

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Letras Departamento de Linguística, Português e Línguas Clássicas Programa de Pós-graduação em Linguística Classes Lexicais e Gramaticalização: Adjetivos em Línguas Geneticamente Não Relacionadas Marcus Vinicius de Lira Ferreira Brasília Distrito Federal 2015 Marcus Vinicius de Lira Ferreira Classes Lexicais e Gramaticalização: Adjetivos em Línguas Geneticamente Não Relacionadas Tese apresentada ao Departamento de Linguística Línguas Clássicas e Português do Instituto de Le- tras da Universidade de Brasília, como requisito para a obtenção do grau de Doutor em Linguística. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Heloisa M. M. L. de A. Salles Marcus Vinicius de Lira Ferreira Classes Lexicais e Gramaticalização: Adjetivos em Línguas Geneticamente Não Relacionadas Tese apresentada ao Departamento de Linguística Línguas Clássicas e Português do Instituto de Le- tras da Universidade de Brasília, como requisito para a obtenção do grau de Doutor em Linguística. Aprovada em: _______________________________________________________________ Banca Examinadora Profa. Dra. Heloisa Maria Moreira Lima de A. Salles – LIP/UnB Prof. Dr. Aroldo Leal Andrade – UNICAMP/FAPESP Profa. Dra. Helena Guerra Vicente – LIP/UnB Prof. Dr. Marcus Vinicius da Silva Lunguinho – LIP/UnB Profa. Dra. Walkiria Neiva Praça – LIP/UnB Profa. Dra. Rozana Reigota Naves – LIP/UnB 「 薫 人 へ 間 は 、 自 由 と い う 刑 に 処 せ ら れ て い る 」 i Agradecimentos 55 meses. 60 línguas. 197 referências. E, até agora, 3 endoscopias... Que valeram a pena! Foi um doutorado bastante atípico – começado após voltar de férias num Japão que pas- sou (comigo lá!) pelo quarto maior terremoto já registrado, por um maremoto, e pelo pior aci- dente nuclear da história do país; e terminado numa sexta-feira treze calma em Brasília (até porque, se formos comparar com o início, venhamos e convenhamos é difícil pensar numa situação que não seja calma!). -

The Finnish Korean Connection: an Initial Analysis

The Finnish Korean Connection: An Initial Analysis J ulian Hadland It has traditionally been accepted in circles of comparative linguistics that Finnish is related to Hungarian, and that Korean is related to Mongolian, Tungus, Turkish and other Turkic languages. N.A. Baskakov, in his research into Altaic languages categorised Finnish as belonging to the Uralic family of languages, and Korean as a member of the Altaic family. Yet there is evidence to suggest that Finnish is closer to Korean than to Hungarian, and that likewise Korean is closer to Finnish than to Turkic languages . In his analytic work, "The Altaic Family of Languages", there is strong evidence to suggest that Mongolian, Turkic and Manchurian are closely related, yet in his illustrative examples he is only able to cite SIX cases where Korean bears any resemblance to these languages, and several of these examples are not well-supported. It was only in 1927 that Korean was incorporated into the Altaic family of languages (E.D. Polivanov) . Moreover, as Baskakov points out, "the Japanese-Korean branch appeared, according to (linguistic) scien tists, as a result of mixing altaic dialects with the neighbouring non-altaic languages". For this reason many researchers exclude Korean and Japanese from the Altaic family. However, the question is, what linguistic group did those "non-altaic" languages belong to? If one is familiar with the migrations of tribes, and even nations in the first five centuries AD, one will know that the Finnish (and Ugric) tribes entered the areas of Eastern Europe across the Siberian plane and the Volga. -

Name of DDO/Hoo ADDRESS-1 ADDRESS CITY PIN SECTION REF

Name of DDO/HoO ADDRESS-1 ADDRESS CITY PIN SECTION REF. NO. BARCODE DATE THE SUPDT OF POLICE (ADMIN),SPL INTELLIGENCE COUNTER INSURGENCY FORCE ,W B,307,GARIA GROUP MAIN ROAD KOLKATA 700084 FUND IX/OUT/33 ew484941046in 12-11-2020 1 BENGAL GIRL'S BN- NCC 149 BLCK G NEW ALIPUR KOLKATA 0 0 KOLKATA 700053 FD XIV/D-325 ew460012316in 04-12-2020 2N BENAL. GIRLS BN. NCC 149, BLOCKG NEW ALIPORE KOL-53 0 NEW ALIPUR 700053 FD XIV/D-267 ew003044527in 27-11-2020 4 BENGAL TECH AIR SAQ NCC JADAVPUR LIMIVERSITY CAMPUS KOLKATA 0 0 KOLKATA 700032 FD XIV/D-313 ew460011823in 04-12-2020 4 BENGAL TECH.,AIR SQN.NCC JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY CAMPUS, KOLKATA 700036 FUND-VII/2019-20/OUT/468 EW460018693IN 26-11-2020 6 BENGAL BATTALION NCC DUTTAPARA ROAD 0 0 N.24 PGS 743235 FD XIV/D-249 ew020929090in 27-11-2020 A.C.J.M. KALYANI NADIA 0 NADIA 741235 FD XII/D-204 EW020931725IN 17-12-2020 A.O & D.D.O, DIR.OF MINES & MINERAL 4, CAMAC STREET,2ND FL., KOLKATA 700016 FUND-XIV/JAL/19-20/OUT/30 ew484927906in 14-10-2020 A.O & D.D.O, O/O THE DIST.CONTROLLER (F&S) KARNAJORA, RAIGANJ U/DINAJPUR 733130 FUDN-VII/19-20/OUT/649 EW020926425IN 23-12-2020 A.O & DDU. DIR.OF MINES & MINERALS, 4 CAMAC STREET,2ND FL., KOLKATA 700016 FUND-IV/2019-20/OUT/107 EW484937157IN 02-11-2020 STATISTICS, JT.ADMN.BULDS.,BLOCK-HC-7,SECTOR- A.O & E.O DY.SECY.,DEPTT.OF PLANNING & III, KOLKATA 700106 FUND-VII/2019-20/OUT/470 EW460018716IN 26-11-2020 A.O & EX-OFFICIO DY.SECY., P.W DEPTT. -

Environmental and Ecological Change: Gleanings from Copperplate Inscriptions of Early Bengal

Indian Journal of History of Science, 54.1 (2019) 119-124 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2019/v54i1/49606 Project Report Environmental and Ecological Change: Gleanings from Copperplate Inscriptions of Early Bengal Rajat Sanyal INTRODUCTION of the Vaga region (6th century CE); Candra and Varman kings (9th–10th century CE) Historically defined, the geographical orbit of Bengal (comprising present Indian state of West • Southeastern Bengal: Copperplate of Bengal and the independent Republic of Vainyagupta from Comilla (5th century CE); Bangladesh) witnessed the consolidation of human Deva, Rāta and Khaga kings from Comilla settlements of the historical phase from almost the (7th–8th century CE) and Copperplates of Deva middle of the first millennium BCE. It is from the kings of Comilla-Noakhali (13th century CE) third century BCE level that proper archaeological The above classificatory scheme vindicates five and epigraphic evidence from some parts of the geochronological ‘categories’ in the inscriptional region show the growth and expansion of large corpus of Bengal: the Gupta plates of fifth–sixth scale urban settlements. centuries, the post-Gupta plates of sixth century The geographical and chronological distri- hailing from eastern and southwestern Bengal, bution of copperplate inscriptions of early Bengal those of the local lineages of sixth–eight centuries, clearly suggest the four different geographical plates of the Pāla and their contemporaries of sectors from which they were issued. These are: eighth–twelfth centuries and those of the Sena and a. northern Bengal, b. western-southwestern their subordinates of twelfth–thirteenth centuries. Bengal, c. eastern Bengal and d. southeastern The primary methodology followed in this Bengal. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

Origins of the Japanese Languages. a Multidisciplinary Approach”

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master’s Thesis “Origins of the Japanese languages. A multidisciplinary approach” verfasst von / submitted by Patrick Elmer, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2019 / Vienna 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 843 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Japanologie UG2002 degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Mag. Dr. Bernhard Seidl Mitbetreut von / Co-Supervisor: Dr. Bernhard Scheid Table of contents List of figures .......................................................................................................................... v List of tables ........................................................................................................................... v Note to the reader..................................................................................................................vi Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................... vii 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Research question ................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Methodology ........................................................................................................