A Practical Approach To, Diagnosis, Assessment and Management Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CD-P-PH/PHO) Report Classification/Justifica

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES AS REGARDS THEIR SUPPLY (CD-P-PH/PHO) Report classification/justification of medicines belonging to the ATC group R01 (Nasal preparations) Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 5 DISCLAIMER 7 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT 8 ACTIVE SUBSTANCES Cyclopentamine (ATC: R01AA02) 10 Ephedrine (ATC: R01AA03) 11 Phenylephrine (ATC: R01AA04) 14 Oxymetazoline (ATC: R01AA05) 16 Tetryzoline (ATC: R01AA06) 19 Xylometazoline (ATC: R01AA07) 20 Naphazoline (ATC: R01AA08) 23 Tramazoline (ATC: R01AA09) 26 Metizoline (ATC: R01AA10) 29 Tuaminoheptane (ATC: R01AA11) 30 Fenoxazoline (ATC: R01AA12) 31 Tymazoline (ATC: R01AA13) 32 Epinephrine (ATC: R01AA14) 33 Indanazoline (ATC: R01AA15) 34 Phenylephrine (ATC: R01AB01) 35 Naphazoline (ATC: R01AB02) 37 Tetryzoline (ATC: R01AB03) 39 Ephedrine (ATC: R01AB05) 40 Xylometazoline (ATC: R01AB06) 41 Oxymetazoline (ATC: R01AB07) 45 Tuaminoheptane (ATC: R01AB08) 46 Cromoglicic Acid (ATC: R01AC01) 49 2 Levocabastine (ATC: R01AC02) 51 Azelastine (ATC: R01AC03) 53 Antazoline (ATC: R01AC04) 56 Spaglumic Acid (ATC: R01AC05) 57 Thonzylamine (ATC: R01AC06) 58 Nedocromil (ATC: R01AC07) 59 Olopatadine (ATC: R01AC08) 60 Cromoglicic Acid, Combinations (ATC: R01AC51) 61 Beclometasone (ATC: R01AD01) 62 Prednisolone (ATC: R01AD02) 66 Dexamethasone (ATC: R01AD03) 67 Flunisolide (ATC: R01AD04) 68 Budesonide (ATC: R01AD05) 69 Betamethasone (ATC: R01AD06) 72 Tixocortol (ATC: R01AD07) 73 Fluticasone (ATC: R01AD08) 74 Mometasone (ATC: R01AD09) 78 Triamcinolone (ATC: R01AD11) 82 -

Composition for Rectal Administration Combined with an Oral Alpha-Lipoic

(19) & (11) EP 2 162 125 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A61K 31/136 (2006.01) A61K 31/01 (2006.01) 19.10.2011 Bulletin 2011/42 A61P 1/00 (2006.01) A61K 45/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/56 (2006.01) A61K 31/573 (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 08768441.1 A61K 31/606 (22) Date of filing: 13.06.2008 (86) International application number: PCT/US2008/007401 (87) International publication number: WO 2008/156671 (24.12.2008 Gazette 2008/52) (54) Composition for rectal administration combined with an oral alpha-lipoic acid composition for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease Zusammensetzung zur rektalen Verabreichung kombiniert mit einer oralen Zusammentzung enthaltend alpha Liponsäure zur Behandlung von entzündlicher Darmerkrankung Composition pour l’administration rectale en combinaison avec une composition orale de l’ acide alpha- lipoique pour le traitment des maladies intestinales inflammatoires (84) Designated Contracting States: (56) References cited: AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR EP-B1- 0 671 168 WO-A2-02/089796 HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MT NL NO PL PT US-A- 4 657 900 US-A- 5 082 651 RO SE SI SK TR US-A- 5 378 470 (30) Priority: 13.06.2007 US 934505 P • MULDER CJ. ET AL.: ’Beclomethasone 06.02.2008 US 63745 P dipropionate (3mg) versus 5- aminosalicylic acid (2g) versus the combination of both (3mg/2g)as (43) Date of publication of application: retention enemas in active ulcerative proctitis’ 17.03.2010 Bulletin 2010/11 EUR.J.GASTROENTEROL HEPATOL vol. -

Inhaled Corticosteroid (ICS) Only – Metered Dose Inhalers (MDI)

Categorisation and Formulary Choices of Inhaled Corticosteroids for Adults Inhaled Corticosteroid (ICS) only – Metered Dose Inhalers (MDI) MDI Beclometasone dipropionate Use with a compatible Fluticasone Propionate spacer device Prescribe by BRAND Clenil Modulite® Qvar®(extrafine) Qvar®(extrafine) Flixotide® Evohaler MDI Easi-Breathe Low Dose 100mcg, two puffs twice a 50 mcg, two puffs twice a day 50 mcg, two puffs twice a day 50 mcg, two puffs twice a day (BDP equivalent day (200 dose) (200 dose) (200 dose) (120 dose) ≤400mcg BDP) £4.45/month £4.72/month £4.64/month £5.44/month Medium Dose 200mcg, two puffs twice a 100 mcg, two puffs twice a day 100 mcg, two puffs twice a day 125mcg, two puffs twice a day (BDP equivalent day (200 dose) (200 dose) (200 dose) (120 dose) 400-1000mcg BDP) £9.70/month £10.33/month £10.17/month £12.50/month High Dose 250mcg, two puffs twice a 100 mcg, four puffs twice a day 100 mcg, four puffs twice a day 250mcg, two puffs twice a day (BDP equivalent day (200 dose) (200 dose) (200 dose) (120 dose) >1000mcg BDP) £9.77/month £20.66/month £20.34/month £20.00/month Simultaneous specialist OR referral recommended 250mcg four puffs, twice a day (200 dose) £19.55/month Prices correct as per Drug Tariff and DM&D December2018 1st line choices (dark green, solid border) 2nd line choices (light green, dashed border) Approved by Hertfordshire Medicines Management Committee – October 2018 Inhaled Corticosteroid (ICS) only – Dry Powder Inhalers (DPI) Beclometasone DPI dipropionate Budesonide Fluticasone Propionate Prescribe -

BSG Plan for IBD Patients During COVID19 Pandemic V1.5 349.88 KB

British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) advice for management of inflammatory bowel diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic Date of publication: 22nd March 2020 Introduction Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), comprising Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a condition in which the gastrointestinal immune system responds inappropriately. It is therefore often treated with immune suppression medications to control inflammation and to prevent ‘flares’, a worsening in symptoms, which may be unpredictable. It is known that 0.8% of people in the UK (approx. 524,000 patients) currently have IBD, but only 44% have been to a clinic in the last 3 years1,2. There will be many patients who will be worried about the effect of the Coronavirus pandemic (SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 disease) on their IBD and vice versa. During the COVID-19 outbreak we will do everything we can to keep our IBD patients safe. The biggest risks are related not only to the infection itself, but also the emergency reorganisation of hospital and general practice services to deal with the pandemic, meaning routine IBD services will be significantly affected. A combined approach covering both primary and secondary care is therefore required to keep vulnerable IBD patients out of hospital as much as possible. Insights from Hubei, China and from Italy suggest hospital admission for non-COVID-19 illness will provide a reservoir for further spread of infection. However, alterations to the way we deliver IBD care in the UK must be balanced against the risks of undertreated, active IBD. Importantly, patients with active IBD are likely to have a higher risk of infection both in the community and during inpatient care, even in the absence of immunosupressant treatment3. -

FF/UMEC/VI) Triple Therapy Versus Tiotropium Monotherapy in Patients with COPD

www.nature.com/npjpcrm ARTICLE OPEN Single-inhaler fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol (FF/UMEC/VI) triple therapy versus tiotropium monotherapy in patients with COPD Sandeep Bansal1, Martin Anderson2, Antonio Anzueto3,4, Nicola Brown5, Chris Compton6, Thomas C. Corbridge7,8, David Erb9, Catherine Harvey5, Morrys C. Kaisermann10, Mitchell Kaye11, David A. Lipson 10,12, Neil Martin6,13, Chang-Qing Zhu5 and ✉ Alberto Papi 14 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) treatment guidelines do not currently include recommendations for escalation directly from monotherapy to triple therapy. This 12-week, double-blind, double-dummy study randomized 800 symptomatic moderate-to-very-severe COPD patients receiving tiotropium (TIO) for ≥3 months to once-daily fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/ vilanterol (FF/UMEC/VI) 100/62.5/25 mcg via ELLIPTA (n = 400) or TIO 18 mcg via HandiHaler (n = 400) plus matched placebo. Study endpoints included change from baseline in trough forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) at Days 85 (primary), 28 and 84 (secondary), health status (St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire [SGRQ] and COPD Assessment Test [CAT]) and safety. FF/UMEC/VI significantly improved trough FEV1 at all timepoints (Day 85 treatment difference [95% CI] 95 mL [62–128]; P < 0.001), and significantly improved SGRQ and CAT versus TIO. Treatment safety profiles were similar. Once-daily single-inhaler FF/UMEC/VI significantly improved lung function and health status versus once-daily TIO in symptomatic moderate-to-very-severe COPD 1234567890():,; patients, with a similar safety profile. npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2021) 31:29 ; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-021-00241-z INTRODUCTION performed to date and a lack of updated recommendations Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of based on the current body of evidence. -

Utah Medicaid Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee Drug

Utah Medicaid Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee Drug Class Review Single Ingredient Nasal Corticosteroids Beclomethasone dipropionate (Qnasl) Beclomethasone dipropionate monohydrate (Beconase AQ) Budesonide (Rhinocort) Ciclesonide (Omnaris, Zetonna) Flunisolide (Generic) Fluticasone Furoate (Flonase Sensimist) Fluticasone Propionate (Flonase, Xhance) Mometasone Furoate (Nasonex) Triamcinolone Acetonide (Nasacort) AHFS Classification: 52.08.08 Corticosteroids (EENT) Final Report February 2018 Review prepared by: Valerie Gonzales, Pharm.D., Clinical Pharmacist Elena Martinez Alonso, B.Pharm., MSc MTSI, Medical Writer Vicki Frydrych, Pharm.D., Clinical Pharmacist Joanita Lake, B.Pharm., MSc EBHC (Oxon), Research Assistant Professor Joanne LaFleur, Pharm.D., MSPH, Associate Professor University of Utah College of Pharmacy University of Utah College of Pharmacy, Drug Regimen Review Center Copyright © 2018 by University of Utah College of Pharmacy Salt Lake City, Utah. All rights reserved Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Table 1. Nasal corticosteroid products ............................................................................................. -

Pharmacology/Therapeutics II Block III Lectures 2013-14

Pharmacology/Therapeutics II Block III Lectures 2013‐14 66. Hypothalamic/pituitary Hormones ‐ Rana 67. Estrogens and Progesterone I ‐ Rana 68. Estrogens and Progesterone II ‐ Rana 69. Androgens ‐ Rana 70. Thyroid/Anti‐Thyroid Drugs – Patel 71. Calcium Metabolism – Patel 72. Adrenocorticosterioids and Antagonists – Clipstone 73. Diabetes Drugs I – Clipstone 74. Diabetes Drugs II ‐ Clipstone Pharmacology & Therapeutics Neuroendocrine Pharmacology: Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones, March 20, 2014 Lecture Ajay Rana, Ph.D. Neuroendocrine Pharmacology: Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones Date: Thursday, March 20, 2014-8:30 AM Reading Assignment: Katzung, Chapter 37 Key Concepts and Learning Objectives To review the physiology of neuroendocrine regulation To discuss the use neuroendocrine agents for the treatment of representative neuroendocrine disorders: growth hormone deficiency/excess, infertility, hyperprolactinemia Drugs discussed Growth Hormone Deficiency: . Recombinant hGH . Synthetic GHRH, Recombinant IGF-1 Growth Hormone Excess: . Somatostatin analogue . GH receptor antagonist . Dopamine receptor agonist Infertility and other endocrine related disorders: . Human menopausal and recombinant gonadotropins . GnRH agonists as activators . GnRH agonists as inhibitors . GnRH receptor antagonists Hyperprolactinemia: . Dopamine receptor agonists 1 Pharmacology & Therapeutics Neuroendocrine Pharmacology: Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones, March 20, 2014 Lecture Ajay Rana, Ph.D. 1. Overview of Neuroendocrine Systems The neuroendocrine -

QVAR™ (BECLOMETASONE DIPROPIONATE) AUTOHALER™ and QVAR™ (BECLOMETASONE DIPROPIONATE) INHALER 1 NAME of the MEDICINE Beclometasone Dipropionate

AUSTRALIAN PRODUCT INFORMATION – QVAR™ (BECLOMETASONE DIPROPIONATE) AUTOHALER™ and QVAR™ (BECLOMETASONE DIPROPIONATE) INHALER 1 NAME OF THE MEDICINE Beclometasone dipropionate 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Beclometasone dipropionate (BDP) is a white to creamy white, odourless powder; it is slightly soluble in water, very soluble in chloroform and freely soluble in acetone and alcohol. QVAR also contains ethanol and norflurane (HFA-134a), a propellant which does not contain chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Excipients with known effects: ethanol (alcohol) 11.85 % v/v. QVAR 50 Inhaler and Autohaler deliver 50 µg of BDP per inhalation. QVAR 100 Inhaler and Autohaler deliver 100 µg of BDP per inhalation. QVAR Autohaler is a breath actuated inhaler which automatically releases a metered dose of medication during inhalation through the mouthpiece and overcomes the need for patients to coordinate actuation with inspiration. QVAR Inhaler is a conventional press and breathe metered dose inhaler (P&B MDI). There are no differences in formulation between the Autohaler and the Inhaler products. QVAR contains BDP in solution, resulting in an extra fine aerosol. The aerosol droplets of QVAR are on average much smaller (Mass Median Aerodynamic Diameter (MMAD), MMAD range 0.8 to 1.2 microns) than the particle sizes delivered by CFC-suspension formulations (MMAD range 3.5 to 4 microns) or dry powder formulations (MMAD approximately 10 microns) of BDP. The smaller particle size for QVAR results in greater deposition in the airways and less deposition in the oropharynx than beclometasone products formulated in CFCs. Radiolabelled deposition studies demonstrated that for QVAR the majority of BDP (>55 % dose ex actuator) is deposited in the lungs and a small amount (< 35 % dose ex actuator) is deposited in the oropharynx. -

Identification and Validation of Novel Hpxr Activators Amongst

DMD Fast Forward. Published on November 10, 2010 as DOI: 10.1124/dmd.110.035808 DMD FastThis Forward. article has not Published been copyedited on andNovember formatted. The 10, final 2010 version as maydoi:10.1124/dmd.110.035808 differ from this version. DMD #35808 Identification and Validation of Novel hPXR Activators Amongst Prescribed Drugs via Ligand-Based Virtual Screening Yongmei Pan, Linhao Li, Gregory Kim, Sean Ekins, Hongbing Wang and Peter W. Swaan Downloaded from Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland, 20 Penn Street, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA; Collaborations in Chemistry, Jenkintown, PA 19046, USA (SE); Department of Pharmacology, University of Medicine & Dentistry dmd.aspetjournals.org of New Jersey (UMDNJ)-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA (SE). at ASPET Journals on September 24, 2021 1 Copyright 2010 by the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. DMD Fast Forward. Published on November 10, 2010 as DOI: 10.1124/dmd.110.035808 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. DMD #35808 a) Running Title: Identification of Novel hPXR Activators b) Corresponding Author: Peter W. Swaan, Ph.D., Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Maryland, 20 Penn Street, HSF2-621, Baltimore, MD 21201 USA Tel: (410) 706-0103 Fax: (410) 706-5017 Email: [email protected] Downloaded from c) Number of: Text pages: 35 dmd.aspetjournals.org Tables: 3 Figures: 6 References: 45 at ASPET Journals on September 24, 2021 Words in Abstract: 196 Words in Introduction: 546 Words in Discussion: 1,521 d) Abbreviations: hPXR, Human pregnane X receptor; LBD, ligand binding domain; XV ROC AUC, Leave-one-out cross-validation based ‘receiver operator curve’ area under the curve. -

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

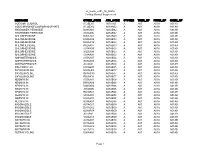

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01 -

Beclometasone for Asthma

information for parents and carersrs Beclometasone inhaler for asthma prevention (prophylaxis) This leafl et is about the use of inhaled beclometasone for asthma. It is taken regularly in order to prevent attacks. (This is sometimes called asthma prophylaxis.) This leafl et has been written for parents and carers about how The dose will be shown on the medicine label. to use this medicine in children. Our information sometimes It is important that you follow your doctor’s differs from that provided by the manufacturers, because their instructions about how much to give. information is usually aimed at adult patients. Please read this leafl et carefully. Keep it somewhere safe so that you can How should I give beclometasone? read it again. Your doctor or asthma nurse will show you how to use the aerosol inhaler and spacer device. Beclometasone inhalers should not be used during Detailed information on how to use the inhalers is given an acute asthma attack (sudden onset of wheezing on the last page of this leafl et. and breathlessness). Use your child’s reliever medicine (usually in a blue salbutamol inhaler). When should the medicine start working? Beclometasone needs to be given regularly to prevent Name of drug asthma and wheeze. Your child should start to wheeze less, Beclometasone dipropionate (often known as and to need less reliever medicine, 3–7 days after starting beclometasone for short) treatment. Continue to give the medicine, as told to by your It comes in a variety of different aerosol and dry powder doctor or nurse, even if your child does not have any wheeze inhalers, which have different brand names. -

World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines, 21St List, 2019

World Health Organizatio n Model List of Essential Medicines 21st List 2019 World Health Organizatio n Model List of Essential Medicines 21st List 2019 WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06 © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines, 21st List, 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris.