Travels in North America, with Geological Observations on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Medina, Clinton, and Lockport Groups) in the Type Area of Western New York

Revised Stratigraphy and Correlations of the Niagaran Provincial Series (Medina, Clinton, and Lockport Groups) in the Type Area of Western New York By Carlton E. Brett, Dorothy H. Tepper, William M. Goodman, Steven T. LoDuca, and Bea-Yeh Eckert U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2086 Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences of the University of Rochester UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1995 10 REVISED STRATIGRAPHY AND CORRELATIONS OF THE NIAGARAN PROVINCIAL SERIES been made in accordance with the NASC. Because the The history of nomenclature of what is now termed the NASC does not allow use of the "submember" category, Medina Group, beginning with Conrad ( 1837) and ending units that would be of this rank are treated as informal units with Bolton (1953), is presented in Fisher (1954); Bolton and have been given alphanumeric designations. Informal (1957, table 2) presents a detailed summary of this nomen- units are discussed under the appropriate "member" clature for 1910-53. A historical summary of nomenclature categories. of the Medina Group in the Niagara region is shown in fig- The use of quotes for stratigraphic nomenclature in this ure 7. Early investigators of the Medina include Conrad report is restricted to units that have been misidentified or (1837); Vanuxem (1840, first usage of Medina; 1842); Hall abandoned. If stratigraphic nomenclature for a unit has (1840, 1843); Gilbert (1899); Luther (1899); Fairchild changed over time, the term for the unit is shown, with cap- (1901); Grabau (1901, 1905, 1908, 1909, 1913); Kindle and italization, as given in whatever reference is cited rather Taylor (1913); Kindle (1914); Schuchert (1914); Chadwick than according to the most recent nomenclature. -

Figure 3A. Major Geologic Formations in West Virginia. Allegheney And

82° 81° 80° 79° 78° EXPLANATION West Virginia county boundaries A West Virginia Geology by map unit Quaternary Modern Reservoirs Qal Alluvium Permian or Pennsylvanian Period LTP d Dunkard Group LTP c Conemaugh Group LTP m Monongahela Group 0 25 50 MILES LTP a Allegheny Formation PENNSYLVANIA LTP pv Pottsville Group 0 25 50 KILOMETERS LTP k Kanawha Formation 40° LTP nr New River Formation LTP p Pocahontas Formation Mississippian Period Mmc Mauch Chunk Group Mbp Bluestone and Princeton Formations Ce Obrr Omc Mh Hinton Formation Obps Dmn Bluefield Formation Dbh Otbr Mbf MARYLAND LTP pv Osp Mg Greenbrier Group Smc Axis of Obs Mmp Maccrady and Pocono, undivided Burning Springs LTP a Mmc St Ce Mmcc Maccrady Formation anticline LTP d Om Dh Cwy Mp Pocono Group Qal Dhs Ch Devonian Period Mp Dohl LTP c Dmu Middle and Upper Devonian, undivided Obps Cw Dhs Hampshire Formation LTP m Dmn OHIO Ct Dch Chemung Group Omc Obs Dch Dbh Dbh Brailler and Harrell, undivided Stw Cwy LTP pv Ca Db Brallier Formation Obrr Cc 39° CPCc Dh Harrell Shale St Dmb Millboro Shale Mmc Dhs Dmt Mahantango Formation Do LTP d Ojo Dm Marcellus Formation Dmn Onondaga Group Om Lower Devonian, undivided LTP k Dhl Dohl Do Oriskany Sandstone Dmt Ot Dhl Helderberg Group LTP m VIRGINIA Qal Obr Silurian Period Dch Smc Om Stw Tonoloway, Wills Creek, and Williamsport Formations LTP c Dmb Sct Lower Silurian, undivided LTP a Smc McKenzie Formation and Clinton Group Dhl Stw Ojo Mbf Db St Tuscarora Sandstone Ordovician Period Ojo Juniata and Oswego Formations Dohl Mg Om Martinsburg Formation LTP nr Otbr Ordovician--Trenton and Black River, undivided 38° Mmcc Ot Trenton Group LTP k WEST VIRGINIA Obr Black River Group Omc Ordovician, middle calcareous units Mp Db Osp St. -

Structural Geology of the Transylvania Fault Zone in Bedford County, Pennsylvania

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Master's Theses Graduate School 2009 STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY OF THE TRANSYLVANIA FAULT ZONE IN BEDFORD COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA Elizabeth Lauren Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Elizabeth Lauren, "STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY OF THE TRANSYLVANIA FAULT ZONE IN BEDFORD COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA" (2009). University of Kentucky Master's Theses. 621. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_theses/621 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF THESIS STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY OF THE TRANSYLVANIA FAULT ZONE IN BEDFORD COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA Transverse zones cross strike of thrust-belt structures as large-scale alignments of cross-strike structures. The Transylvania fault zone is a set of discontinuous right-lateral transverse faults striking at about 270º across Appalachian thrust-belt structures along 40º N latitude in Pennsylvania. Near Everett, Pennsylvania, the Breezewood fault terminates with the Ashcom thrust fault. The Everett Gap fault terminates westward with the Hartley thrust fault. Farther west, the Bedford fault extends westward to terminate against the Wills Mountain thrust fault. The rocks, deformed during the Alleghanian orogeny, are semi-independently deformed on opposite sides of the transverse fault, indicating fault movement during folding and thrusting. Palinspastic restorations of cross sections on either side of the fault zone are used to compare transverse fault displacement. -

Key, M. M., Jr. and N. Potter, Jr. 1992

Guidebook for the llth Annual Field Trip of the Harrisburg Area Geological Society May 9, 1992 Paleozoic Geology of the Paw Paw-Hancock Area of Maryland and West Virginia by Marcus M. Key, Jr. and Noel Potter, Jr. Dickinson College TABLE OF CONTENTS . .. List of F1gures . .............................................. 111 Introduction . ....................................... · ......... 1 Road Log • ..•... • ..... · .... • •.....•....•...•......• e ••• '0 ••••••••• 3 Stop 1. Roundtop Hill . ............ o •••••••••• o •••••••••••••••••• 5 stop 2. Sideling Hill Road Cut ..•.••............••.••••......... 8 Stop 3. Sideling Hill Diamictite Exposure ....•.•....•.•....•... 11 Stop 4. Cacapon Mountain Overlook .••.......•......•.•••••...... 15 Stop 5. Fluted Rocks Overlook .•..•••.••....•.•.•••.•........... 16 Stop 6. Fluted Rocks ................. .,. .......... ., o ••••• ., •••••• • 19 Stop 7. Berkeley Springs state Park •...•.....................•. 20 Acknowled·gments . ........................... :- ... e ••••••••••••••• 21 References .....••.•..•.•••.•..•.•..•.••......................•. 2 2 Topogrpphic maps covering field trip stops: USGS 7 1/2 minute quadrangles Bellegrove (MD-PA-WV), Great Cacapon (WV-MD), Hancock (WV-MD-PA) Cover Photo: Anticline in Silurian Bloomsburg Formation. From Stose and swartz (1912). The anticline is visible from the towpath of the c & 0 Canal at Roundtop Hill (Stop# 1). Guidebook copies may be obtained by writing: Harrisburg Area Geological Society cjo Pennsylvania Geological Survey P.O. Box 2357 Harrisburg, -

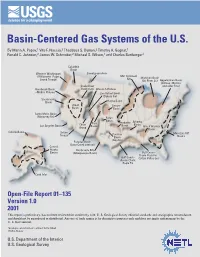

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. by Marin A

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. By Marin A. Popov,1 Vito F. Nuccio,2 Thaddeus S. Dyman,2 Timothy A. Gognat,1 Ronald C. Johnson,2 James W. Schmoker,2 Michael S. Wilson,1 and Charles Bartberger1 Columbia Basin Western Washington Sweetgrass Arch (Willamette–Puget Mid-Continent Rift Michigan Basin Sound Trough) (St. Peter Ss) Appalachian Basin (Clinton–Medina Snake River and older Fms) Hornbrook Basin Downwarp Wasatch Plateau –Modoc Plateau San Rafael Swell (Dakota Fm) Sacramento Basin Hanna Basin Great Denver Basin Basin Santa Maria Basin (Monterey Fm) Raton Basin Arkoma Park Anadarko Los Angeles Basin Chuar Basin Basin Group Basins Black Warrior Basin Colville Basin Salton Mesozoic Rift Trough Permian Basin Basins (Abo Fm) Paradox Basin (Cane Creek interval) Central Alaska Rio Grande Rift Basins (Albuquerque Basin) Gulf Coast– Travis Peak Fm– Gulf Coast– Cotton Valley Grp Austin Chalk; Eagle Fm Cook Inlet Open-File Report 01–135 Version 1.0 2001 This report is preliminary, has not been reviewed for conformity with U. S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature, and should not be reproduced or distributed. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U. S. Government. 1Geologic consultants on contract to the USGS 2USGS, Denver U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey BASIN-CENTERED GAS SYSTEMS OF THE U.S. DE-AT26-98FT40031 U.S. Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory Contractor: U.S. Geological Survey Central Region Energy Team DOE Project Chief: Bill Gwilliam USGS Project Chief: V.F. -

Subsurface Facies Analysis of the Clinton Sandstone, Located in Perry, Fairfield, and Vinton Counties

SUBSURFACE FACIES ANALYSIS OF THE CLINTON SANDSTONE, LOCATED IN PERRY, FAIRFIELD, AND VINTON COUNTIES Craig Allen Stouten A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2014 Committee: James Evans, Advisor Charles Onasch Jeff Snyder ii ABSTRACT James Evans, Advisor This paper focuses on the depositional environment of the “Clinton Sandstone” located in Perry, Fairfield, and Vinton Counties in central and southeastern Ohio. Core from wells numbered 2866, 2941, 2942, 2943, 2965, and 2980 were accessed from the Ohio Geological Survey, H.R. Collins Core Laboratory. Each core was described, photographed, and sampled for thin sections and lithofacies analysis. In addition, gamma-ray and neutron density logs were acquired for each well. The geophysical logs were used for litho-correlation and to examine 3-D architecture. This new data was used to re-evaluate the depositional interpretations. The “Clinton Sandstone” is an informal name given to the Lower Silurian sandstone unit that stratigraphically lies between the Cabot Head Shale and the Neagha Shale in southeastern Ohio. The “Clinton Sandstone” correlates with the Tuscarora Sandstone in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Confusingly, the “Clinton Sandstone” is not related to the Upper Silurian Clinton Group located in western New York. Previous workers have interpreted the “Clinton Sandstone” to be part of a wide range of environments, from fluvial-deltaic to a strand plain, and incorporating tidal channels, delta plains, crevasse-splays, and offshore marine deposits. This study confirms some, but not all of the previous interpretations, finding the “Clinton Sandstone” to be part of a delta plain, delta front, and prodelta environment. -

Geologic Resources Inventory Ancillary Map Information Document

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Directorate Geologic Resources Division Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site and Johnstown Flood National Memorial GRI Ancillary Map Information Document Produced to accompany the Geologic Resources Inventory (GRI) Digital Geologic-GIS Data for Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site and Johnstown Flood National Memorial alpo_jofl_geology.pdf Version: 5/11/2020 I Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site and Johnstown Flood National Memorial Geologic Resources Inventory Map Document for Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site and Johnstown Flood National Memorial Table of Contents Geologic Resourc..e..s.. .I.n..v..e..n..t.o...r.y.. .M...a..p.. .D...o..c..u..m...e...n..t............................................................................ 1 About the NPS Ge..o..l.o..g..i.c... .R..e..s..o..u...r.c..e..s.. .I.n..v..e..n...t.o..r.y.. .P...r.o..g...r.a..m............................................................... 3 GRI Digital Maps a..n...d.. .S..o..u...r.c..e.. .M...a..p.. .C...i.t.a..t.i.o...n..s.................................................................................. 5 Index Map .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Digital Bedrock Geologic-GIS Map of Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site, John..s..t..o..w...n.. .F..l.o..o...d.. .N...a..t.i.o..n..a..l. .M...e..m...o...r.i.a..l. .a..n..d... .V..i.c..i.n..i.t.y.................................................. 7 Map Unit Lis.t................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Map Unit De.s..c..r.i.p..t.io..n..s...................................................................................................................................................... 8 PNcc - Cas.s..e..l.m...a..n. -

Summary of Investigations in Late Paleozoic Geology of Ohio1 2

Copyright © 1979 Ohio Acad. Sci. SUMMARY OF INVESTIGATIONS IN LATE PALEOZOIC GEOLOGY OF OHIO1 2 MYRON T. STURGEON, Department of Geology, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701 Abstract. This report summarizes the development of our understanding of the stratigraphy, paleontology and economic geology of the Carboniferous and Permian Systems of Ohio, and can conveniently be divided into four time units: prior to 1869, 1869-1900, 1900-1949 and 1949 to the present. The first period was a time during which animals and Indians sought essential mineral substances and early explorers reported on geologic features and resources. Notes and reports were published on newly established mineral industries during and after settlement. This period also included publication of two annual reports de- scribing the accomplishments of the short-lived First Ohio Geological Survey in the mid-1830's and publication of notes by individuals on general geology, fossils and mineral resources of the State between 1840 and the Civil War. Systematic investi- gation and reporting on Ohio's geology really began with the establishment of the Second Ohio Geological Survey in 1869 and has continued under three subsequent surveys. The distinguished staff of the Second Survey prepared and published reports on stratigraphy, fossils and mineral resources and the first geologic map including accompanying structure and stratigraphic sections. The Third Survey increased the emphasis on economic geology in its publications, and the Fourth and present Surveys have continued this attention in their appropriate reports and maps. In 1949 the Survey became a division in the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. OHIO J. SCI. 79(3): 99, 1979 This summary pertains to the develop- and most sources of other cited references ment of our understanding of the geology are available in the bibliography, where of the Carboniferous and Permian Sys- a total of more than 600 references are tems in Ohio, with emphasis on stratig- available. -

Gas Accumulation in the Lower Silurian "Clinton" Sands, Medina Group, and Tuscarora Sandstone in the Appalachian Basin: a Progress Report of 1995 Project Activities

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Possible continuous-type (unconventional) gas accumulation in the Lower Silurian "Clinton" sands, Medina Group, and Tuscarora Sandstone in the Appalachian basin: A progress report of 1995 project activities Robert T. Ryder 1, Kerry L. Aggen2, Robert D. Hettinger2, Ben E. Law2 , John J. Miller2, Vito F. Nuccio2, William J. Perry, Jr.2, Stephen E. Prensky2, John R. SanFilipol, and Craig J. Wandrey2 Open-File Report 96-42 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the USGS. U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 22092 U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado 80225 CONTENTS Page inti oQ.ucij.on -L Objectives and research strategy .................................... 4 Sandstone character and depositional sequences along selected transects ....................................................... D Gas production and decline of selected wells ......................... 25 Data storage and digital maps ........................................ 27 Structure-contour and drilling-depth maps.......................... 31 Reservoir temperature and pressure ................................ 33 Downdip limit of water production .................................. 35 Burial, thermal, and petroleum generation history models........... 36 Fractures and their detection with log suites ........................ 40 -

Ironstones, Condensed Beds, and Sequence Stratigraphy of the Clinton Group (Lower Silurian) in Its Type Area, Central New York

Ironstones, condensed beds, and sequence stratigraphy of the Clinton Group (Lower Silurian) in its type area, central New York Nicholas Sullivan [[email protected]] Department of Geology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221-0013 Carlton E. Brett [[email protected]] Department of Geology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221-0013 Patrick McLaughlin [[email protected]] Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, 3817 Mineral Point Rd., Madison, WI 53705 ABSTRACT The fossiliferous and oolitic ironstones of the Clinton Group (Silurian, late Llandovery to early Wenlock) in central New York have inspired considerable interest since the early surveys of Eaton in the 1820s. Although these ores have never been mined on industrial scales, they were processed extensively up to the mid 1900s for oxides used in red paints. Three of these horizons, Westmoreland, "basal Dawes" or Salmon Creek, and Kirkland, will be examined and discussed on this excursion, with emphasis placed on their sedimentology, taphonomy, correlation, and regional significance in the context of depositional cycles. Recent work has recast these classic deposits in the context of sequence stratigraphy, wherein ironstones and related phosphatic and shelly deposits are viewed as condensed facies: the product of siliciclastic sediment starvation during periods of rapid transgression at the bases of small- and large -scale depositional sequences. These strata and the environmental conditions they represent will also be considered in the context of recently collected geochemical and geophysical data, which have implications for the correlation of these sections and their importance with regard to regional and global environmental changes and bioevents. B5-1 1. INTRODUCTION Although iron rich horizons in the sedimentary record are the subject of numerous studies, many critical questions remain concerning the processes of their formation (see Van Houten and Bhattacharyya, 1982; Kimberley, 1994 and references therein). -

Geologic Assessment of the Burger Power Plant and Surrounding Vicinity for Potential Injection of Carbon Dioxide

Geologic Assessment of the Burger Power Plant and Surrounding Vicinity for Potential Injection of Carbon Dioxide By Lawrence H. Wickstrom, Ernie R. Slucher, Mark T. Baranoski, and Douglas J. Mullett Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Geological Survey 2045 Morse Road, Building C-1 Columbus, Ohio 43229-6693 Columbus 2008 Open-File Report 2008-1 ABOUT THE MRCSP This report was produced by the Ohio Division of Geological Survey with funding supplied, in part, through the Midwest Regional Carbon Sequestration Partnership (MRCSP). The MRCSP is a public/private consor- tium that is assessing the technical potential, economic viability, and public acceptability of carbon sequestra- tion within its region. The MRCSP region consists of eight contiguous states: Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. A group of leading universities, state geological surveys, non-governmental organizations and private companies makes up the MRCSP, which is led by Bat- telle Memorial Institute. It is one of seven such partnerships across the United States that make up the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Regional Carbon Sequestration Partnership Program. The U.S. DOE, through the National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL), contributes the majority of funds for the MRCSP’s re- search under agreement no. DE-FC26-05NT42589. The MRCSP also receives funding from all of the member organizations. For more information on the partnership please visit <http://www.mrcsp.org>. DISCLAIMER The information contained herein has not been technically reviewed for accuracy and conformity with pres- ent Ohio Division of Geological Survey standards for published materials. The Ohio Division of Geological Survey does not guarantee this information to be free from errors, omissions, or inaccuracies and disclaims any responsibility or liability for interpretations or decisions based thereon. -

Petrology, Stratigraphy, and Depositional History of the Upper Triassic-Lower Jurassic Eagle Mills Formation, Choctaw County, Alabama

Petrology, Stratigraphy, and Depositional History of the Upper Triassic-Lower Jurassic Eagle Mills Formation, Choctaw County, Alabama Donald E. Burch, Jr.,1 and A. E. Weidie2 Consultant, 935 Gravier St., New Orleans, LA 70112 department of Geology and Geophysics, University of New Orleans, New Orleans, LA 70148 Extended Abstract In southwestern Choctaw County, Alabama, the Eagle Mills Formation consists of alluvial-fan red beds deposited in a Mesozoic graben. The Exxon No. 1 Smith Lumber Co. well penetrated the upper 2,210 ft of the Eagle Mills, and it is divided into eight lithostratigraphic units designated A through H from bottom to top. Unit A consists of numerous upward-fining and -coarsening sequences of sandstones, conglomeratic sandstones, and conglomerates of variable thickness separated by red mudstones. They were deposited on the distal fan by ephemeral streams and sheetfloods and are composed of low-grade metamorphic rock fragments probably derived from the Talladega slate belt. Unit B consists of red mudstone with interbedded upward-fining and -coarsening sandstones and conglomerates with abundant calcite concretions and paleocaliche. Thin-section analyses of three sandstones of Unit B show that two are phyllarenites and one is a subphyllarenite. They vary from very fine to coarse-grained and are moderately sorted and submature, with angular to subangular framework grains. Quartz (subequal monocrystalline and polycrystalline) is the dominant framework grain with lesser amounts of schist and phyllite. In the two shallower sandstones, quartz content decreases as chert and dolomite marble rock fragments increase. Scanning electron microscope examination of one sandstone shows the presence of large well-developed pores lined with illite and authigenic quartz.