Long Report Template with Cover Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surat Basin Non-Resident Population Projections, 2021 to 2025

Queensland Government Statistician’s Office Surat Basin non–resident population projections, 2021 to 2025 Introduction The resource sector in regional Queensland utilises fly-in/fly-out Figure 1 Surat Basin region and drive-in/drive-out (FIFO/DIDO) workers as a source of labour supply. These non-resident workers live in the regions only while on-shift (refer to Notes, page 9). The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) official population estimates and the Queensland Government’s population projections for these areas only include residents. To support planning for population change, the Queensland Government Statistician’s Office (QGSO) publishes annual non–resident population estimates and projections for selected resource regions. This report provides a range of non–resident population projections for local government areas (LGAs) in the Surat Basin region (Figure 1), from 2021 to 2025. The projection series represent the projected non-resident populations associated with existing resource operations and future projects in the region. Projects are categorised according to their standing in the approvals pipeline, including stages of In this publication, the Surat Basin region is defined as the environmental impact statement (EIS) process, and the local government areas (LGAs) of Maranoa (R), progress towards achieving financial close. Series A is based Western Downs (R) and Toowoomba (R). on existing operations, projects under construction and approved projects that have reached financial close. Series B, C and D projections are based on projects that are at earlier stages of the approvals process. Projections in this report are derived from surveys conducted by QGSO and other sources. Data tables to supplement the report are available on the QGSO website (www.qgso.qld.gov.au). -

Quarterly Energy Dynamics Q3 2018

Quarterly Energy Dynamics Q3 2018 Author: Market Insights | Markets Important notice PURPOSE AEMO has prepared this report to provide energy market participants and governments with information on the market dynamics, trends and outcomes during Q3 2018 (1 July to 30 September 2018). This quarterly report compares results for the quarter against other recent quarters, focussing on Q2 2018 and Q3 2017. Geographically, the report covers: • The National Electricity Market – which includes Queensland, New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. • The Wholesale Electricity Market operating in Western Australia. • The gas markets operating in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. DISCLAIMER This document or the information in it may be subsequently updated or amended. This document does not constitute legal or business advice, and should not be relied on as a substitute for obtaining detailed advice about the National Electricity Law, the National Electricity Rules, the Wholesale Electricity Market Rules, the National Gas Law, the National Gas Rules, the Gas Services Information Regulations or any other applicable laws, procedures or policies. AEMO has made every effort to ensure the quality of the information in this document but cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Accordingly, to the maximum extent permitted by law, AEMO and its officers, employees and consultants involved in the preparation of this document: • make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the currency, accuracy, reliability or completeness of the information in this document; and • are not liable (whether by reason of negligence or otherwise) for any statements or representations in this document, or any omissions from it, or for any use or reliance on the information in it. -

Surat Basin Population Report, 2020

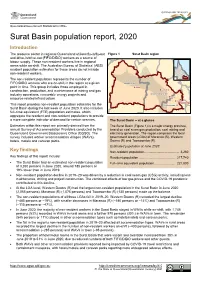

Queensland Government Statistician’s Office Surat Basin population report, 2020 Introduction The resource sector in regional Queensland utilises fly-in/fly-out Figure 1 Surat Basin region and drive-in/drive-out (FIFO/DIDO) workers as a source of labour supply. These non-resident workers live in regional areas while on-shift. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) resident population estimates for these areas do not include non-resident workers. The non-resident population represents the number of FIFO/DIDO workers who are on-shift in the region at a given point in time. This group includes those employed in construction, production, and maintenance at mining and gas industry operations, renewable energy projects and resource-related infrastructure. This report provides non-resident population estimates for the Surat Basin during the last week of June 2020. It also includes full–time equivalent (FTE) population estimates, which aggregate the resident and non-resident populations to provide a more complete indicator of demand for certain services. The Surat Basin – at a glance Estimates within this report are primarily derived from the The Surat Basin (Figure 1) is a major energy province, annual Survey of Accommodation Providers conducted by the based on coal seam gas production, coal mining and Queensland Government Statistician’s Office (QGSO). The electricity generation. The region comprises the local survey includes worker accommodation villages (WAVs), government areas (LGAs) of Maranoa (R), Western hotels, motels and caravan parks. Downs (R) and Toowoomba (R). Estimated population at June 2020: Key findings Non-resident population ....................................... 3,260 Key findings of this report include: Resident population ........................................ -

Suboptimal Supercritical Reliability Issues at Australia’S Supercritical Coal Power Plants

Suboptimal supercritical Reliability issues at Australia’s supercritical coal power plants There have been recent calls for Australian taxpayers to subsidise the building of supercritical coal power plants (so-called “HELE” plants), but existing supercritical plants experience frequent breakdowns that affect electricity prices and can push grid frequency outside of safe ranges. Discussion paper Mark Ogge Bill Browne January 2019 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more just, sustainable and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. -

Queensland Coals

QUEENSLAND COALS Physical and Chemical Properties, Colliery and Company Information 14th Edition 2003 Compiled by Andrew J. Mutton Geoscientific Advisor Department of Natural Resources and Mines Bureau of Mining and Petroleum Level 3 41 George Street Brisbane Queensland 4000 Australia GPO Box 2454 Brisbane Queensland 4001 Australia Ph: +61 7 3237 1480 Fax: +61 7 3237 1534 Published by: Department of Natural Resources and Mines GPO Box 2454 Brisbane Qld 4001 Australia ISSN 1442-1836 QNRM03327 Project management by Bureau of Mining and Petroleum Compiled by: A.J. Mutton Desktop publishing: S.A. Beeston (Geological Survey of Queensland) Graphics: T.S. Moore and L.M. Blight Editing and proofreading: G.P. Ayling and S.A. Beeston Printed by: ColourWise Reproductions Cover background: Coal being stacked, Moura Mine (photograph courtesy Anglo Coal Australia Pty Ltd) © The State of Queensland (Department of Natural Resources and Mines) 2003 Copyright protects this publication. Copyright enquiries should be addressed to: The Director, Product Marketing GPO Box 2454 Brisbane Qld 4001 Ph: (07) 3405 5553 Fax: (07) 3405 5567 Limited reproduction of information in this publication is permitted. Material sourced from this publication for reproduction in other printed or electronic publications must be acknowledged and duly referenced as follows: Mutton, A.J. (Compiler), 2003: Queensland Coals 14th Edition. Queensland Department of Natural Resources and Mines. Printed copies of this report are available from: Department of Natural Resources and Mines Sales Centre, Level 2, Mineral House 41 George St Brisbane Qld 4000 Ph: (07) 3237 1435 (International +61 7 3237 1435) Email: [email protected] Acknowledgments Information in this edition originates from mining companies and other coal industry sources, and from technical and statistical records held by the Department of Natural Resources and Mines. -

Hansard 26 November 2002

26 Nov 2002 Legislative Assembly 4693 TUESDAY, 26 NOVEMBER 2002 Mr SPEAKER (Hon. R. K. Hollis, Redcliffe) read prayers and took the chair at 9.30 a.m. ASSENT TO BILLS Government House Queensland 14 November 2002 The Honourable R. K. Hollis, MP Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Parliament House George Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Dear Mr Speaker I hereby acquaint the Legislative Assembly that the following Bills, having been passed by the Legislative Assembly and having been presented for the Royal Assent, were assented to in the name of Her Majesty The Queen on 14 November 2002: "A Bill for an Act to amend the Juvenile Justice Act 1992 and the Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 to facilitate the provision of drug assessment and education sessions to particular offenders appearing before drug diversion courts" "A Bill for an Act to amend the Ambulance Service Act 1991, Fire and Rescue Service Act 1990 and State Counter- Disaster Organisation Act 1975" "A Bill for an Act to amend the Business Names Act 1962 and Fair Trading Act 1989" "A Bill for an Act to amend the Integrated Resort Development Act 1987" "A Bill for an Act to amend the Mineral Resources Act 1989" "A Bill for an Act to amend the Mineral Resources Act 1989, and for other purposes" "A Bill for an Act to provide for the racing industry in Queensland, including betting on races and sporting contingencies, and for other purposes". The Bills are hereby transmitted to the Legislative Assembly, to be numbered and forwarded to the proper Officer for enrolment, in the manner required by law. -

Modelling Air Quality in the Surat Basin, Queensland PDF 15 MB

CSIRO OCEANS AND ATMOSPHERE Modelling air quality in the Surat Basin, Queensland Julie Noonan, Martin Cope, Sarah J. Lawson, Jennifer C. Powell, Suzie Molloy, Marcus Thatcher and Kathryn Emmerson 2019 Final Report for the Gas Industry Social and Environmental Research Alliance (GISERA), Project No G.3 ISBN (print): 978-1-4863-1285-6 ISBN (online): 978-1-4863-1286-3 Citation Julie Noonan, Martin Cope, Sarah J. Lawson, Jennifer C. Powell, Suzie Molloy, Marcus Thatcher and Kathryn Emmerson, 2019 Modelling air quality in the Surat Basin, Queensland 2019, CSIRO, Australia. Copyright © Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation 2019. To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any averages except with the written permission of CSIRO. Important disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. CSIRO is committed to providing web accessible content wherever possible. -

Coal and Coal Seam Gas Resource Assessment for the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine Subregion

1 Coal and coal seam gas resource assessment for the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine subregion Product 1.2 for the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine subregion from the Northern Inland Catchments Bioregional Assessment 28 October 2014 A scientific collaboration between the Department of the Environment, Bureau of Meteorology, CSIRO and Geoscience Australia The Bioregional Assessment Programme The Bioregional Assessment Programme is a transparent and accessible programme of baseline assessments that increase the available science for decision making associated with coal seam gas and large coal mines. A bioregional assessment is a scientific analysis of the ecology, hydrology, geology and hydrogeology of a bioregion with explicit assessment of the potential direct, indirect and cumulative impacts of coal seam gas and large coal mining development on water resources. This Programme draws on the best available scientific information and knowledge from many sources, including government, industry and regional communities, to produce bioregional assessments that are independent, scientifically robust, and relevant and meaningful at a regional scale. The Programme is funded by the Australian Government Department of the Environment. The Department of the Environment, Bureau of Meteorology, CSIRO and Geoscience Australia are collaborating to undertake bioregional assessments. For more information, visit <http://www.bioregionalassessments.gov.au>. Department of the Environment The Office of Water Science, within the Australian Government Department of the Environment, is strengthening the regulation of coal seam gas and large coal mining development by ensuring that future decisions are informed by substantially improved science and independent expert advice about the potential water related impacts of those developments. For more information, visit <http://www.environment.gov.au/coal-seam-gas-mining/>. -

Power Station Controls Capability Statement

POWER STATION CONTROLS CAPABILITY STATEMENT 1. Introduction Provecta Process Automation LLC, based in Chicago, is an Australian-owned controls and electrical professional engineering services company specializing in high-level automation and advanced control solutions for the power generation industry. Provecta has developed an international reputation as a consistent deliverer of highest quality, cost- effective projects and innovative control design solutions. Projects and services have been delivered to clients throughout Australia and worldwide. Our senior engineers’ extensive experience in power plant operations, performance and investigations as well as in control system design, implementation and optimisation uniquely positions us to take all aspects of the client’s environment into account when forming our solutions. This ensures control projects – ranging from adjustments to full equipment replacements - meet each generating station’s individual requirements, and to ensure projects deliver the required benefits. 2. Background Provecta Australia was formed in 2003 by nine senior control system professionals specializing in the power generation industry. The company has grown to become one of Australia’s largest independent control system project and consultancy providers operating in the power and water critical infrastructure industries. International clients, particularly in the USA, have been increasingly drawing on Provecta’s expertise to help meet changing operational demands such as faster ramping, improved frequency response, -

Coal Out: Fossil Fuel Power Station Breakdowns in Queensland

Coal Out: Fossil fuel power station breakdowns in Queensland Over 2018 and 2019 there were more breakdowns at Queensland’s gas and coal power stations than in any other National Electricity Market (NEM) state. Queensland’s newer supercritical coal power stations had disproportionally high rates of breakdown with Australia’s newest coal power station at Kogan Creek, the most unreliable single generating unit in the NEM. Discussion paper Mark Ogge Audrey Quicke Bill Browne September 2020 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more just, sustainable and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. -

TSBE Annual Report 2015 – 2016 Contents

Annual Report 2015 - 2016 TSBE LINKING BUSINESS INVESTMENT ATTRACTION ADVOCACY FOR OUR REGION Foreword What a wonderful year this has been. TSBE has worked hard to deliver for the region, and returned to surplus as planned following a decision last year to invest significant funds in successfully establishing our China presence. As you read through the following report you’ll be able to see some of the key undertakings and achievements for the region as well as gaining an understanding of TSBE’s core activities; advocating, linking businesses, and attracting investment to the region. Our region is well and truly primed for growth. As is regularly reported, the combined impact of key road, air and future rail infrastructure is propagating opportunities. TSBE’s position remains to capitalise on these opportunities and deliver sustainable growth and diversity to our region. There has never been a more exciting time to live, work and play in the region. TSBE can’t be successful without support from the business community. We are humbled by the support we receive from our foundation partner, Toowoomba Regional Council and our key regional partners Maranoa, Western Downs and South Burnett regional councils. We would also not be here today without the highly valued support and engagement of our media partners, Southern Cross Austereo and APN Australian Regional Media or 20 our platinum members. I look forward to seeing the exciting achievements we will be able to share with you in 2016 - 2017 Shane Charles Executive Chairman TSBE 2 / TSBE Annual -

Archer's Accommodation Group

accommodation group “In recognition of the pioneering achievements of the Archer Brothers in the discovery and development of Western Downs and Central Queensland regions.” miles - theodore - blackwater - mt morgan - gracemere - kinka beach Archer’s Accommodation Group • Archer’s Accommodation Village – Miles – 3100 rooms • Archer’s Motor Inn – Theodore – 110 rooms • Archer’s Executive Villas – Blackwater – 31 rooms • Archer’s Residential Development – Mt Morgan – 1800 rooms • Archer’s Serviced Apartments – Gracemere – 135 rooms • Archer’s Tourist Park – Kinka Beach – 300 rooms • room2move.com Mobile Camp Accommodation - any place any time Further enquiries Phone: 1800 20 04 08 Email: [email protected] © Letter from the CEO “It is with great pleasure that I have the opportunity on behalf of Landtrak Corporation Ltd to introduce one of the largest resource related accommodation projects to be undertaken in the Western Downs Region. In the 1800‘s when Charles Archer came to the area looking for a place to run sheep he was following the footsteps of the explorer Thomas Mitchell. But this wasn’t only about farming. Charles Archer was bringing a new life to an old land. A life for his family and the start of a new community. Now, there is a new group of explorers offering renewed life for the old land and the emergance of a new community. Archer’s Accommodation Village is that community. It is a focus, a home and a community for the new explorers in the gas fields of the Surat Basin. It is designed to compliment and expand Miles Community and to respect the area’s rural history.