Hallel: a Liturgical Composition Celebrating the Exodus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women As Shelihot Tzibur for Hallel on Rosh Hodesh

MilinHavivinEng1 7/5/05 11:48 AM Page 84 William Friedman is a first-year student at YCT Rabbinical School. WOMEN AS SHELIHOT TZIBBUR FOR HALLEL ON ROSH HODESH* William Friedman I. INTRODUCTION Contemporary sifrei halakhah which address the issue of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh are unanimous—they are entirely exempt (peturot).1 The basis given by most2 of them is that hallel is a positive time-bound com- mandment (mitzvat aseh shehazman gramah), based on Sukkah 3:10 and Tosafot.3 That Mishnah states: “One for whom a slave, a woman, or a child read it (hallel)—he must answer after them what they said, and a curse will come to him.”4 Tosafot comment: “The inference (mashma) here is that a woman is exempt from the hallel of Sukkot, and likewise that of Shavuot, and the reason is that it is a positive time-bound commandment.” Rosh Hodesh, however, is not mentioned in the list of exemptions. * The scope of this article is limited to the technical halakhic issues involved in the spe- cific area of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh as it compares to that of men. Issues such as changing minhag, kol isha, areivut, and the proper role of women in Jewish life are beyond that scope. 1 R. Imanu’el ben Hayim Bashari, Bat Melekh (Bnei Brak, 1999), 28:1 (82); Eliyakim Getsel Ellinson, haIsha vehaMitzvot Sefer Rishon—Bein haIsha leYotzrah (Jerusalem, 1977), 113, 10:2 (116-117); R. David ben Avraham Dov Auerbakh, Halikhot Beitah (Jerusalem, 1982), 8:6-7 (58-59); R. -

Yamim Noraim Flyer 12-Pg 5771

Days of Awe ………….. 5771 Rabbi Linda Holtzman • Rabbi Yael Levy Dina Schlossberg, President • Rabbit Brian Walt, Rabbi Emeritus Gabrielle Kaplan Mayer, Coordinator of Spiritual Life for Children & Youth Rivka Jarosh, Education Director 4101 Freeland Avenue • Philadelphia, PA 19128 Phone: 215-508-0226 • Fax: 215-508-0932 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.mishkan.org DAYS OF AWE 5771 Shalom, Welcome to a year of opportunity at Mishkan Shalom! Our first of many opportunities will be that of starting the year together at services for the Yamim Noraim. It is a pleasure to begin the year as a community, joining old friends and new, praying and learning together. This year, Rabbi Yael Levy will not be with us at the services for the Yamim Noraim. We will miss Rabbi Yael, and hope that her sabbatical time is fulfilling and energizing and that we will learn much from her when she returns to Mishkan Shalom in November. Our services will feel different this year, but the depth and talent of our many members who will participate will add real beauty to them. I am thrilled that joining us to lead the davening will be Sue Hoffman, Rabbi Rebecca Alpert, Cindy Shapiro, Karen Escovitz (Otter), Elliott batTzedek, Wendy Galson, Susan Windle, Andy Stone, Bill Grey, Dan Wolk, several of our teens and many other Mishkan members. As we look ahead to the new year, we pray that 5771 will be filled with abundant blessings for us and for the world. I look forward to celebrating with you. L’shalom, Rabbi Linda Holtzman SECTION 1: LOCATION , VOLUNTEER FORM , FEES AND SERVICE INFORMATION A: WE HAVE • Morning services on the first day of Rosh Hashanah and all services on Yom Kippur will be held at the Haverford School . -

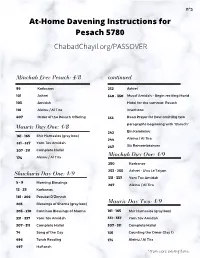

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

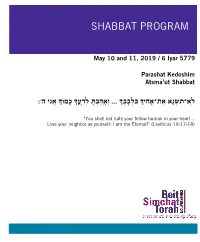

Shabbat Program Shabbat Program

SHABBAT PROGRAM SHABBAT PROGRAM May 10 and 11, 2019 / 6 Iyar 5779 Parashat Kedoshim Atsma’ut Shabbat ֽא־תִשׂ�נָא אֶת־אָחִי בִּלְבָבֶ ... ו�אָֽהַבְתָּ לְ�ֽעֲ כָּמוֹ אֲנִי ה': "You shall not hate your fellow human in your heart… Love your neighbor as yourself: I am the Eternal!" (Leviticus 19:17-18) 1 Welcome to CBST! ברוכים וברוכות הבאים לקהילת בית שמחת תורה! קהילת בית שמחת תורה מקיימת קשר רב שנים ועמוק עם ישראל, עם הבית הפתוח בירושלים לגאווה ולסובלנות ועם הקהילה הגאה בישראל. אנחנו מזמינים אתכם\ן לגלוּת יהדוּת ליבראלית גם בישראל! מצאו את המידע על קהילות רפורמיות המזמינות אתכם\ן לחגוג את סיפור החיים שלכן\ם בפלאיירים בכניסה. לפרטים נוספים ניתן לפנות לרב נועה סתת: [email protected] 2 MAY 10, 2019 / 6 IYAR 5779 ATSMA’UT SHABBAT- PARASHAT KEDOSHIM הֲכָנַת הַלֵּב OPENING PRAYERS AND MEDITATIONS *Od Yavo Shalom Aleinu Mosh Ben Ari (Born 1971) עוד יבוא שלום עלינו 101 (Peace will yet come to us and to everyone) L’chah Dodi Mordechai Zeira (1905-1968) לְכָה דוֹדִי Program Arr. Yehezkel Braun (1922-2014) *(Candle Blessings Abraham Wolf Binder (1895-1967 הַדְ לָקַת נֵרוֹת שׁ�ל שׁ�בָּת 38 *(Shalom Aleichem Israel Goldfarb (1879-1956 שׁ�לוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם 40 קַבָּלַת שׁ�בָּת KABBALAT SHABBAT / WELCOMING SHABBAT *L’chu N’ran’na Reuben Sirotkin (Born 1933) לְכוּ נְ�נְּנָה (תהלים צה) 52 (Psalm 95) (Yir’am Hayam (Psalm 98) Yoel Sykes (Born 1986 י��עַם הַיּ�ם (תהלים צו) 54 Nava Tehilah (Jerusalem)* *Mizmor L’David (Psalm 29) Yoel Sykes (Born 1986) מִזְמוֹר לְדָו�ד (תהלים כט) 62 *L'chah Dodi (Shlomo Alkabeitz) Kehilat Tsiyon (Jerusalem) לְכָה דוֹדִי 66 Kol Haneshama -

Halachic Minyan”

Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shvat 5768 Intoduction 3 Minyan 8 Weekdays 8 Rosh Chodesh 9 Shabbat 10 The Three Major Festivals Pesach 12 Shavuot 14 Sukkot 15 Shemini Atzeret/Simchat Torah 16 Elul and the High Holy Days Selichot 17 High Holy Days 17 Rosh Hashanah 18 Yom Kippur 20 Days of Thanksgiving Hannukah 23 Arba Parshiot 23 Purim 23 Yom Ha’atzmaut 24 Yom Yerushalayim 24 Tisha B’Av and Other Fast Days 25 © Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal [email protected] [email protected] Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” 2 Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shevat 5768 “It is a positive commandment to pray every day, as it is said, You shall serve the Lord your God (Ex. 23:25). Tradition teaches that this “service” is prayer. It is written, serving Him with all you heart and soul (Deut. 2:13), about which the Sages said, “What is service of the heart? Prayer.” The number of prayers is not fixed in the Torah, nor is their format, and neither the Torah prescribes a fixed time for prayer. Women and slaves are therefore obligated to pray, since it is a positive commandment without a fixed time. Rather, this commandment obligates each person to pray, supplicate, and praise the Holy One, blessed be He, to the best of his ability every day; to then request and plead for what he needs; and after that praise and thank God for all the He has showered on him.1” According to Maimonides, both men and women are obligated in the Mitsva of prayer. -

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018 Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 CONTENTS NOTES ....................................................................................................1 DATES OF FESTIVALS .............................................................................2 CALENDAR OF TORAH AND HAFTARAH READINGS 5776-5778 ............3 GLOSSARY ........................................................................................... 29 PERSONAL NOTES ............................................................................... 31 Published by: The Movement for Reform Judaism Sternberg Centre for Judaism 80 East End Road London N3 2SY [email protected] www.reformjudaism.org.uk Copyright © 2015 Movement for Reform Judaism (Version 2) Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 Notes: The Calendar of Torah readings follows a triennial cycle whereby in the first year of the cycle the reading is selected from the first part of the parashah, in the second year from the middle, and in the third year from the last part. Alternative selections are offered each shabbat: a shorter reading (around twenty verses) and a longer one (around thirty verses). The readings are a guide and congregations may choose to read more or less from within that part of the parashah. On certain special shabbatot, a special second (or exceptionally, third) scroll reading is read in addition to the week’s portion. Haftarah readings are chosen to parallel key elements in the section of the Torah being read and therefore vary from one year in the triennial cycle to the next. Some of the suggested haftarot are from taken from k’tuvim (Writings) rather than n’vi’ivm (Prophets). When this is the case the appropriate, adapted blessings can be found on page 245 of the MRJ siddur, Seder Ha-t’fillot. This calendar follows the Biblical definition of the length of festivals. -

The Psalms As Hymns in the Temple of Jerusalem Gary A

4 The Psalms as Hymns in the Temple of Jerusalem Gary A. Rendsburg From as far back as our sources allow, hymns were part of Near Eastern temple ritual, with their performers an essential component of the temple functionaries. 1 These sources include Sumerian, Akkadian, and Egyptian texts 2 from as early as the third millennium BCE. From the second millennium BCE, we gain further examples of hymns from the Hittite realm, even if most (if not all) of the poems are based on Mesopotamian precursors.3 Ugarit, our main source of information on ancient Canaan, has not yielded songs of this sort in 1. For the performers, see Richard Henshaw, Female and Male: The Cu/tic Personnel: The Bible and Rest ~(the Ancient Near East (Allison Park, PA: Pickwick, 1994) esp. ch. 2, "Singers, Musicians, and Dancers," 84-134. Note, however, that this volume does not treat the Egyptian cultic personnel. 2. As the reader can imagine, the literature is ~xtensive, and hence I offer here but a sampling of bibliographic items. For Sumerian hymns, which include compositions directed both to specific deities and to the temples themselves, see Thorkild Jacobsen, The Harps that Once ... : Sumerian Poetry in Translation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), esp. 99-142, 375--444. Notwithstanding the much larger corpus of Akkadian literarure, hymn~ are less well represented; see the discussion in Alan Lenzi, ed., Reading Akkadian Prayers and Hymns: An Introduction, Ancient Near East Monographs (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011), 56-60, with the most important texts included in said volume. For Egyptian hymns, see Jan A%mann, Agyptische Hymnen und Gebete, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999); Andre Barucq and Frarn;:ois Daumas, Hymnes et prieres de /'Egypte ancienne, Litteratures anciennes du Proche-Orient (Paris: Cerf, 1980); and John L. -

Purim-Shofar-2019.Pdf

1 2 Table of Contents Purim Insights…………..………………..……………………..page 3 Special Purim Mitzvahs……………....………………………...page 4 Bnai Torah Purim Schedule……………..…...………………....page 5 Bnai Torah Purim Seudah……………………………………....page 6 March & April Service Schedules……………..………….....Pages 7-8 We wish all our readers a joyous and inspiring Purim! 3 Mishloach Manos There are several reasons given for the mitzvah of Mishloach Manos (sending food gifts) on Purim. Firstly, the mitzvah of Mishloach Manos is designed to enable Jews to enjoy fulfilling the Mitzvah of having a Purim meal. Gifts of prepared food are sent on the day of Purim in order to ensure that all people have the means to enjoy a lavish feast. According to this reason it is necessary for the recipient to accept the Mishloach Manos and not merely for the donor to extend the gift. Another reason for Mishloach Manos is based upon the fact that the Jews of Shushan transgressed the laws of Kashrus by partaking in non-kosher food served at King Achashverosh’s banquet. To demonstrate that they had truly repented from this sin, the mitzvah of Mishloach Manos was inaugurated. By sending food gifts one to another, Jews demonstrated their mutual trust in matters of Kashrus. As in the case of the first reason it is therefore imperative that the recipient accept and not merely that the donor extend the gift. Finally, the sending of Mishloach Manos is to dispel the image of the Jewish People as a “scattered and dis-unified people” depicted by the wicked Haman. By exchanging gifts on the holiday of Purim the Jews demonstrate the strong bonds of friendship and love which truly exist among themselves. -

Sukkot Schedule *All Zmanim Reflect Times in Manhattan

Sukkot Schedule *All Zmanim reflect times in Manhattan Friday, October 2 Erev Sukkot Shacharit 7:30am Candle Lighting 6:17pm Include Shel Shabbat v’Shel Yom Tov, and Shehecheyanu Minchah, Kabbalat Shabbat and Maariv 6:25pm An abridged Kabbalat Shabbat begins with Mizmor Shir Le-Yom ha-Shabbat Omit Ba-Meh Madlikin Kiddush for Shabbat and Yom Tov can be recited after 7:17pm in the Sukkah Recite Leyshev Ba-Sukkah and then Shehecheyanu Ushpizin can be recited every night Shabbat, October 3 Yom Tov, Day 1 Shacharit 9:30am No Lulav and Etrog on Shabbat Full Hallel Torah Reading and Haftarah Vayikra 22:26-23:44, Bemidbar 29:12-16, Zechariah 14:1-21 Yah Eli, Musaf for Yom Tov with Shabbat inclusions Hoshanot for Shabbat (Ohm Netzurah) Hoshanot can be recited at home standing in place Seudah Shlishit in the Sukkah before 5:21pm Mincha/Maariv 6:15pm Candle Lighting and all preparations for 2nd day Yom Tov not before 7:15pm Kiddush for Yom Tov with Havdalah inclusions in the Sukkah Recite Shehecheyanu and then Leyshev Ba-Sukkah Sunday, October 4 Yom Tov, Day 2 Shacharit 9:30am Lulav and Etrog with Shehecheyanu One cannot wear gloves while performing this mitzvah Full Hallel Torah Reading and Haftarah Vayikra 22:26-23:44, Bemidbar 29:12-16, Melachim I 8:2-21 Yah Eli, Musaf for Yom Tov 1 Hoshanot (Lema’an Amitach) Mincha/Maariv 6:25pm Havdalah in the Sukkah (no Leyshev) 7:14pm Monday through Thursday, October 5-8 Shacharit 7:15am Lulav and Etrog Full Hallel Torah Reading M: Bemidbar 29:17-25, T: Bemidbar 29:20-28, W: -

Wordplay in Genesis 2:25-3:1 and He

Vol. 42:1 (165) January – March 2014 WORDPLAY IN GENESIS 2:25-3:1 AND HE CALLED BY THE NAME OF THE LORD QUEEN ATHALIAH: THE DAUGHTER OF AHAB OR OMRI? YAH: A NAME OF GOD THE TRIAL OF JEREMIAH AND THE KILLING OF URIAH THE PROPHET SHEPHERDING AS A METAPHOR SAUL AND GENOCIDE SERAH BAT ASHER IN RABBINIC LITERATURE PROOFTEXT THAT ELKANAH RATHER THAN HANNAH CONSECRATED SAMUEL AS A NAZIRITE BOOK REVIEW: ONKELOS ON THE TORAH: UNDERSTANDING THE BIBLE BOOK REVIEW: JPS BIBLE COMMENTARY: JONAH LETTER TO THE EDITOR www.jewishbible.org THE JEWISH BIBLE QUARTERLY In cooperation with THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, THE JEWISH AGENCY AIMS AND SCOPE The Jewish Bible Quarterly provides timely, authoritative studies on biblical themes. As the only Jewish-sponsored English-language journal devoted exclusively to the Bible, it is an essential source of information for anyone working in Bible studies. The Journal pub- lishes original articles, book reviews, a triennial calendar of Bible reading and correspond- ence. Publishers and authors: if you would like to propose a book for review, please send two review copies to BOOK REVIEW EDITOR, POB 29002, Jerusalem, Israel. Books will be reviewed at the discretion of the editorial staff. Review copies will not be returned. The Jewish Bible Quarterly (ISSN 0792-3910) is published in January, April, July and October by the Jewish Bible Association , POB 29002, Jerusalem, Israel, a registered Israe- li nonprofit association (#58-019-398-5). All subscriptions prepaid for complete volume year only. The subscription price for 2014 (volume 42) is $60. Our email address: [email protected] and our website: www.jewishbible.org . -

NISSAN Rosh Chodesh Is on Sunday

84 NISSAN The Molad: Friday afternoon, 4:36. The moon may be sanctified until Shabbos, the 15th, 10:58 a.m.1 The spring equinox: Friday, the 7th, 12:00 a.m. Rosh Chodesh is on Shabbos Parshas Tazria, Parshas HaChodesh. The laws regarding Shabbos Rosh Chodesh are explained in the section on Shabbos Parshas Mikeitz. In the Morning Service, we recite half-Hallel, then a full Kaddish, the Song of the Day, Barchi nafshi, and then the Mourner’s Kaddish. Three Torah scrolls are taken out. Six men are given aliyos for the weekly reading from the first scroll. A seventh aliyah is read from the second scroll, from which we read the passages describing the Shabbos and Rosh Chodesh Mussaf offerings (Bamidbar 28:9-15), and a half-Kaddish is recited. The Maftir, a passage from Parshas Bo (Sh’mos 12:1-20) which describes the command to bring the Paschal sacrifice, is read from the third scroll. The Haftorah is Koh amar... olas tamid (Y’chezkel 45:18-46:15), and we then add the first and last verses of the Haftorah Koh amar Hashem hashomayim kis’ee (Y’shayahu 66:1, 23- 24, and 23 again). Throughout the entire month of Nissan, we do not recite Tachanun, Av harachamim, or Tzidkas’cha. The only persons who may fast during this month are ones who had a disturbing dream, a groom and bride on the day of their wedding, and the firstborn on the day preceding Pesach. For the first twelve days of the month, we follow the custom of reciting the Torah passages describing the sacrifices which the Nesi’im (tribal leaders) offered on these dates at the time the Sanctuary was dedicated in the desert. -

The Synagogue and Prayer Service

SYNAGOGUE SKILLS: HANDS ON AND BEYOND THE SYNAGOGUE AND PRAYER SERVICE Torah lays out religion based on one Temple located in Jerusalem and a system of daily, weekly, monthly communal sacrifices as well as personal offerings. Even in the earliest times, there was tension between a religion that could only be practiced in one place and Jews living far away. Some tried to build lesser temples but by the time of King Josiah of Judah in the seventh century BCE, the exclusivity of the Temple is firmly established. A new institution began to arise. There were places where it was clearly understood that no sacrifices could or would be offered. No one knows for certain when the synagogue and its alternate form of practice began. One plausible suggestion ties it to the Babylonian exile when the Temple had been destroyed. We have archeological and literary evidence for synagogues as early as the third century BCE in the diaspora and the first century BCE in Israel. The earliest descriptions of synagogues suggest that they were places of study and where knowledge of the Torah was disseminated. An inscription on the floor of a first-century synagogue in Jerusalem describes itself as a place “for reading the law and studying the commandments, and as a hostel with chambers and water installations to provide for the needs of travelers from abroad.” According to Reuven Hammer, “Even at the beginning, the synagogue was a revolutionary institution.” It: Provided for communal worship divorced from sacrifice Could be anywhere; did not have to be in a special or sacred spot.