Marronage, Representation, and Memory in the Great Dismal Swamp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Traditional Plant Knowledge in the Circum-Caribbean Region

Journal of Ethnobiology 23(2): 167-185 Fall/Winter 2003 AFRICAN TRADITIONAL PLANT KNOWLEDGE IN THE CIRCUM-CARIBBEAN REGION JUDITH A. CARNEY Department of Geography, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095 ABSTRACT.—The African diaspora to the Americas was one of plants as well as people. European slavers provisioned their human cargoes with African and other Old World useful plants, which enabled their enslaved work force and free ma- roons to establish them in their gardens. Africans were additionally familiar with many Asian plants from earlier crop exchanges with the Indian subcontinent. Their efforts established these plants in the contemporary Caribbean plant corpus. The recognition of pantropical genera of value for food, medicine, and in the practice of syncretic religions also appears to have played an important role in survival, as they share similar uses among black populations in the Caribbean as well as tropical Africa. This paper, which focuses on the plants of the Old World tropics that became established with slavery in the Caribbean, seeks to illuminate the botanical legacy of Africans in the circum-Caribbean region. Key words: African diaspora, Caribbean, ethnobotany, slaves, plant introductions. RESUME.—La diaspora africaine aux Ameriques ne s'est pas limitee aux person- nes, elle a egalement affecte les plantes. Les traiteurs d'esclaves ajoutaient a leur cargaison humaine des plantes exploitables dAfrique et du vieux monde pour les faire cultiver dans leurs jardins par les esclaves ou les marrons libres. En outre les Africains connaissaient beaucoup de plantes dAsie grace a de precedents echanges de cultures avec le sous-continent indien. -

A Deductive Thematic Analysis of Jamaican Maroons

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sinclair-Maragh, Gaunette; Simpson, Shaniel Bernard Article — Published Version Heritage tourism and ethnic identity: A deductive thematic analysis of Jamaican Maroons Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing Suggested Citation: Sinclair-Maragh, Gaunette; Simpson, Shaniel Bernard (2021) : Heritage tourism and ethnic identity: A deductive thematic analysis of Jamaican Maroons, Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, ISSN 2529-1947, International Hellenic University, Thessaloniki, Vol. 7, Iss. 1, pp. 64-75, http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4521331 , https://www.jthsm.gr/?page_id=5317 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/230516 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ www.econstor.eu Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, Vol. -

Camden County, NC

See Camden County: Dismal Swamp Canal • Dismal Swamp State Park The Historic Dismal Swamp Canal is the oldest continually • Canoe / kayak / bike rentals operating hand-dug canal in the United States.The canal • Walking / biking trails has been placed in the National Register of Historic Places, designated a National Historic Civil Engineering • Boating / paddling / water sports Landmark,recognized as part of the National Underground • Wildlife observation Railroad Network to Freedom Program, and a segment of CAMDEN COUNTY • NC Birding Trail both the North Carolina and Virginia Civil WarTrails. As NORTH CAROLINA • Historical attractions / Civil War Trails/ UGRR an alternate route on the Atlantic IntracoastalWaterway, • Historic Dismal Swamp Canal / ICW beautiful pleasure boats transit the canal daily. • Dismal Swamp Welcome Center • North River Game Land • Recreational fi shing / hunting • Small-town charm • Local restaurants, fl ea markets & produce • Camden County Commerce Park • Select available business/commercial properties along the U.S. 17/I-87 corridor new energy • Superior Schools • Proximity to beautiful beaches • Proximity to Port of Virginia new vision • Business friendly environment • Regional transportation connectivity • UNIQUE NATURAL RESOURCES Dismal Swamp Canal Welcome Center 2356 US Hwy 17 N South Mills, NC 27976-9425 Phone: (252) 771-8333 Email: [email protected] www.dismalswampwelcomecenter.com Camden County Post Offi ce Box 190 117 North NC 343 Camden, NC 27921 Phone: (252) 338-6363 Email: [email protected] -

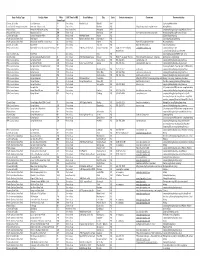

Sorted by Facility Type.Xlsm

Basic Facility Type Facility Name Miles AVG Time In HRS Street Address City State Contact information Comments Known activities (from Cary) Comercial Facility Ace Adventures 267 5 hrs or less Minden Road Oak Hill WV Kayaking/White Water East Coast Greenway Association American Tobacco Trail 25 1 hr or less Durham NC http://triangletrails.org/american- Biking/hiking Military Bases Annapolis Military Academy 410 more than 6 hrs Annapolis MD camping/hiking/backpacking/Military History National Park Service Appalachian Trail 200 5 hrs or less Damascus VA Various trail and entry/exit points Backpacking/Hiking/Mountain Biking Comercial Facility Aurora Phosphate Mine 150 4 hrs or less 400 Main Street Aurora NC SCUBA/Fossil Hunting North Carolina State Park Bear Island 142 3 hrs or less Hammocks Beach Road Swannsboro NC Canoeing/Kayaking/fishing North Carolina State Park Beaverdam State Recreation Area 31 1 hr or less Butner NC Part of Falls Lake State Park Mountain Biking Comercial Facility Black River 90 2 hrs or less Teachey NC Black River Canoeing Canoeing/Kayaking BSA Council camps Blue Ridge Scout Reservation-Powhatan 196 4 hrs or less 2600 Max Creek Road Hiwassee (24347) VA (540) 777-7963 (Shirley [email protected] camping/hiking/copes Neiderhiser) course/climbing/biking/archery/BB City / County Parks Bond Park 5 1 hr or less Cary NC Canoeing/Kayaking/COPE/High ropes Church Camp Camp Agape (Lutheran Church) 45 1 hr or less 1369 Tyler Dewar Lane Duncan NC Randy Youngquist-Thurow Must call well in advance to schedule Archery/canoeing/hiking/ -

The E Slaved People of Patto Pla Tatio Brazoria Cou Ty

Varner-Hogg Plantation and State Historical Park THE ESLAVED PEOPLE OF PATTO PLATATIO BRAZORIA COUTY, TEXAS Research Compiled By Cary Cordova Draft Submitted May 22, 2000 Compiled by Cary Cordova [email protected] Varner-Hogg Plantation and State Historical Park Research Compiled By Cary Cordova THE ESLAVED PEOPLE OF PATTO PLATATIO BRAZORIA COUTY, TEXAS The following is a list of all people known to have been slaves on the Columbus R. Patton Plantation from the late 1830s to 1865 in West Columbia, Texas. The list is by no means comprehensive, but it is the result of compiling information from the probate records, deeds, bonds, tax rolls, censuses, ex-slave narratives, and other relevant historical documents. Each person is listed, followed by a brief analysis if possible, and then by a table of relevant citations about their lives. The table is organized as first name, last name (if known), age, sex, relevant year, the citation, and the source. In some cases, not enough information exists to know much of anything. In other cases, I have been able to determine family lineages and relationships that have been lost over time. However, this is still a work in process and deserves significantly more time to draw final conclusions. Patton Genealogy : The cast of characters can become confusing at times, so it may be helpful to begin with a brief description of the Patton family. John D. Patton (1769-1840) married Annie Hester Patton (1774-1843) and had nine children, seven boys and two girls. The boys were Columbus R. (~1812-1856), Mathew C. -

Qualitative Freedom

Claus Dierksmeier Qualitative Freedom - Autonomy in Cosmopolitan Responsibility Translated by Richard Fincham Qualitative Freedom - Autonomy in Cosmopolitan Responsibility Claus Dierksmeier Qualitative Freedom - Autonomy in Cosmopolitan Responsibility Claus Dierksmeier Institute of Political Science University of Tübingen Tübingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany Translated by Richard Fincham American University in Cairo New Cairo, Egypt Published in German by Published by Transcript Qualitative Freiheit – Selbstbestimmung in weltbürgerlicher Verantwortung, 2016. ISBN 978-3-030-04722-1 ISBN 978-3-030-04723-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04723-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018964905 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

THE PRICE of BONDAGE: SLAVERY, SLAVE VALUATION, and ECONOMICS in the ALBEMARLE by Jacob T. Parks April 2018 Director of Thesis

THE PRICE OF BONDAGE: SLAVERY, SLAVE VALUATION, AND ECONOMICS IN THE ALBEMARLE By Jacob T. Parks April 2018 Director of Thesis: Donald H. Parkerson Major Department: History This thesis examines the economics of antebellum slavery in the Albemarle region of North Carolina. Located in the northeastern corner of the Carolina colony, the Albemarle was a harsh location for settlement and thus, inhabitants settled relatively late by Virginians moving south in search of better opportunities. This thesis finds that examination of a region’s slave economics not only conformed to, but also departed from, the larger slave experience in antebellum America. The introduction of this thesis focuses on the literature surrounding slave economics and valuation in antebellum America. After this, the main body of the thesis follows. Chapter one focuses on the various avenues slaves became property of white men and women in the Albemarle. This reveals that the county courts were intrinsically involved in allowing slave sales to occur, in addition to loop-holes slave owners utilized to retain chattel slavery cheaply. Additionally, this chapter pays special attention to slave valuation and statistical analysis. The following chapters revolve around the topics of: the miscellaneous costs associated with slavery in the Albemarle, such as healthcare, food, and clothing; insuring the lives of slaves and hiring them out for work away from their master; and examination of runaway slave rewards in statistical terms, while also creating a narrative of the enslaved and their actions. THE PRICE OF BONDAGE: SLAVERY, SLAVE VALUATION, AND ECONOMICS IN THE ALBEMARLE A Thesis Presented To the Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History by Jacob Parks April 2018 © Jacob Parks, 2018 THE PRICE OF BONDAGE: SLAVERY, SLAVE VALUATION, AND ECONOMICS IN THE ALBEMARLE by Jacob T. -

500 Miles + 100 Years = Many Race Memories Bobby Unser • Janet Guthrie • Donald Davidson • Bob Jenkins and More!

BOOMER Indy For the best years of your life NEW! BOOMER+ Section Pull-Out for Boomers their helping parents 500 Miles + 100 Years = Many Race Memories Bobby Unser • Janet Guthrie • Donald Davidson • Bob Jenkins and More! Women of the 500 Helping Hands of Freedom Free Summer Concerts MAY / JUNE 2016 IndyBoomer.com There’s more to Unique Home Solutions than just Windows and Doors! Watch for Unique Home Safety on Boomer TV Sundays at 10:30am WISH-TV Ch. 8 • 50% of ALL accidents happen in the home • $40,000+ is average cost of Assisted Living • 1 in every 3 seniors fall each year HANDYMAN TEAM: For all of those little odd jobs on your “Honey Do” list such as installation of pull down staircases, repair screens, clean decks, hang mirrors and pictures, etc. HOME SAFETY DIVISION: Certified Aging in Place Specialists (CAPS) and employee install crews offer quality products and 30+ years of A+ rated customer service. A variety of safe and decorative options are available to help prevent falls and help you stay in your home longer! Local Office Walk-in tubs and tub-to-shower conversions Slip resistant flooring Multi-functional accessory grab bars Higher-rise toilets Ramps/railings Lever faucets/lever door handles A free visit will help you discover fall-hazards and learn about safety options to maintain your independence. Whether you need a picture hung or a total bathroom remodel, Call today for a FREE assessment! Monthy specials 317-216-0932 | geico.com/indianapolis for 55+ and Penny Stamps, CNA Veterans Home Safety Division Coordinator & Certified Aging in Place Specialist C: 317-800-4689 • P: 317.337.9334 • [email protected] 3837 N. -

Freedom As Marronage

Freedom as Marronage Freedom as Marronage NEIL ROBERTS The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London Neil Roberts is associate professor of Africana studies and a faculty affiliate in political science at Williams College. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2015 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2015. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 12746- 0 (cloth) ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 20104- 7 (paper) ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 20118- 4 (e- book) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226201184.001.0001 Jacket illustration: LeRoy Clarke, A Prophetic Flaming Forest, oil on canvas, 2003. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Roberts, Neil, 1976– author. Freedom as marronage / Neil Roberts. pages ; cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 226- 12746- 0 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 226- 20104- 7 (pbk : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 226- 20118- 4 (e- book) 1. Maroons. 2. Fugitive slaves—Caribbean Area. 3. Liberty. I. Title. F2191.B55R62 2015 323.1196'0729—dc23 2014020609 o This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48– 1992 (Permanence of Paper). For Karima and Kofi Time would pass, old empires would fall and new ones take their place, the relations of countries and the relations of classes had to change, before I discovered that it is not quality of goods and utility which matter, but movement; not where you are or what you have, but where you have come from, where you are going and the rate at which you are getting there. -

Nigerian Nationalism: a Case Study in Southern Nigeria, 1885-1939

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1972 Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939 Bassey Edet Ekong Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the African Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ekong, Bassey Edet, "Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939" (1972). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 956. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF' THE 'I'HESIS OF Bassey Edet Skc1::lg for the Master of Arts in History prt:;~'entE!o. 'May l8~ 1972. Title: Nigerian Nationalism: A Case Study In Southern Nigeria 1885-1939. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITIIEE: ranklln G. West Modern Nigeria is a creation of the Britiahl who be cause of economio interest, ignored the existing political, racial, historical, religious and language differences. Tbe task of developing a concept of nationalism from among suoh diverse elements who inhabit Nigeria and speak about 280 tribal languages was immense if not impossible. The tra.ditionalists did their best in opposing the Brltlsh who took away their privileges and traditional rl;hts, but tbeir policy did not countenance nationalism. The rise and growth of nationalism wa3 only po~ sible tbrough educs,ted Africans. -

1995,Brazil's Zumbi Year, Reflections on a Tricentennial Commemoration

1995,Brazil’s Zumbi Year, Reflections on a Tricentennial Commemoration Richard Marin To cite this version: Richard Marin. 1995,Brazil’s Zumbi Year, Reflections on a Tricentennial Commemoration. 2017. hal-01587357 HAL Id: hal-01587357 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01587357 Preprint submitted on 10 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Richard Marin 1995, BRAZIL’S ZUMBI YEAR: REFLECTIONS ON A TRICENTENNIAL COMMEMORATION In 1995, the Brazilian commemorations in honor of the tricentennial of the death of Zumbi, the legendary leader of the large maroon community of Palmares, took on every appearance of a genuine social phenomenon. The Black Movement and part of Brazilian civil society, but also the public authorities, each in different ways, were all committed to marking the event with exceptional grandeur. This article advances a perspective on this commemorative year as an important step in promoting the "Black question" along with Afro-Brazilian identity. After describing the 1995 commemorations, we aim to show how they represented the culmination of already-existing movements that had been at work in the depths of Brazilian society. We will finish by considering the period following the events of 1995, during which "the Black question" becomes truly central to debates in Brazilians society. -

Aquilombar Democracy Fugitive Routes from the End of the World

Working Paper No. 37, 2021 Aquilombar Democracy Fugitive Routes from the End of the World Juliana M. Streva The Mecila Working Paper Series is produced by: The Maria Sibylla Merian International Centre for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences Conviviality-Inequality in Latin America (Mecila), Rua Morgado de Mateus, 615, São Paulo – SP, CEP 04015-051, Brazil. Executive Editors: Susanne Klengel, Lateinamerika-Institut, FU Berlin, Germany Joaquim Toledo Jr., Mecila, São Paulo, Brazil Editing/Production: Fernando Baldraia, Gloria Chicote, Joaquim Toledo Jr., Paul Talcott This working paper series is produced as part of the activities of the Maria Sibylla Merian International Centre for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences Conviviality- Inequality in Latin America (Mecila) funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). All working papers are available free of charge on the Centre website: http://mecila.net Printing of library and archival copies courtesy of the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, Germany. Citation: Streva, Juliana M. (2021): “Aquilombar Democracy: Fugitive Routes from the End of the World”, Mecila Working Paper Series, No. 37, São Paulo: The Maria Sibylla Merian International Centre for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences Conviviality- Inequality in Latin America, http://dx.doi.org/10.46877/streva.2021.37. Copyright for this edition: © Juliana M. Streva This work is provided under a Creative Commons 4.0 Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The text of the license can be read at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode.