Stewart2020.Pdf (618.6Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetic Reformulations of Dwelling in Jo Shapcott, Alice Oswald, and Lavinia Greenlaw

Homecomings: Poetic reformulations of dwelling in Jo Shapcott, Alice Oswald, and Lavinia Greenlaw Janne Stigen Drangsholt, University of Stavanger Abstract In the study The Last of England?, Randall Stevenson refers to the idea of landscape as “the mainstay of poetic imagination” (Stevenson 2004:3). With the rise of the postmodern idiom, our relationship to the “scapes” that surround us has become increasingly problematic and the idea of place is also increasingly deferred and dis- placed. This article examines the relationship between self and “scapes” in the poetries of Jo Shapcott, Alice Oswald and Lavinia Greenlaw, who are all concerned with various “scapes” and who present different, yet connected, strategies for negotiating our relationships to them. Keywords: shifting territories; place; contemporary poetry; postmodernity In The Last of England?, Randall Stevenson points to how the mid- century renunciation of empire was followed by changes that need to be understood primarily in terms of loss. Each of these losses are conceived as marking the last of a certain kind of England, he says, and while another England gradually emerged, this was an England less unified by tradition and more open in outlook, lifestyle, and culture, in short, a place characterised by factors that render it more difficult to define (cf. Stevenson 2004: 1-10). Along with these losses in terms of national character, Stevenson holds, the English landscape also seemed to be increasingly imperilled. While this landscape had traditionally been “the mainstay of poetic imagination” it now seemed in danger of disappearing, as signalled in Philip Larkin’s poem “Going, Going”, where he laments an “England gone, / The shadows, the meadows, the lanes” (Stevenson 2004: 3). -

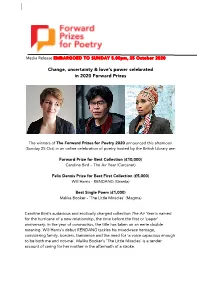

Change, Uncertainty & Love's Power Celebrated in 2020 Forward Prizes

Media Release EMBARGOED TO SUNDAY 5.00pm, 25 October 2020 Change, uncertainty & love’s power celebrated in 2020 Forward Prizes The winners of The Forward Prizes for Poetry 2020 announced this afternoon (Sunday 25 Oct) in an online celebration of poetry hosted by the British Library are: Forward Prize for Best Collection (£10,000) Caroline Bird – The Air Year (Carcanet) Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection (£5,000) Will Harris - RENDANG (Granta) Best Single Poem (£1,000) Malika Booker - ‘The Little Miracles’ (Magma) Caroline Bird’s audacious and erotically charged collection The Air Year is named for the hurricane of a new relationship, the time before the first or ‘paper’ anniversary: in the year of coronavirus, the title has taken on an eerie double meaning. Will Harris’s debut RENDANG tackles his mixed-race heritage, considering family, borders, transience and the need for ‘a voice capacious enough to be both me and not-me’. Malika Booker’s ‘The Little Miracles’ is a tender account of caring for her mother in the aftermath of a stroke. 2 The chair of the 2020 jury, writer, critic and cultural historian Alexandra Harris, commented: ‘We are thrilled to celebrate three winning poets whose finely crafted work has the protean power to change as it meets new readers.’ The Forward Prize for Poetry, founded by William Sieghart and run by the charity Forward Arts Foundation, are the most prestigious awards for new poetry published in the UK and Ireland, and have been sponsored since their launch in 1992 by the content marketing agency, Bookmark (formerly Forward Worldwide). -

Poetry Anthology (Post-2000)

FHS English Department ENGLISH LITERATURE Poems of the Decade: Forward Poetry Anthology (Post-2000) Assessment: Paper 3 Poetry Section A One question from a choice of two, comparing an unseen poem with a named poem from the anthology (30 marks) 1 hour 7 minutes AOs AO1 Articulate informed, personal and creative responses to literary texts, using associated concepts and terminology, and coherent, accurate written expression AO2 Analyse ways in which meanings are shaped in literary texts Terminology *A full glossary of terms can be found on the S Drive/English/KS5/Literature/Poetry Glossary Overview of Poems, Poets and Themes EAT ME CHAINSAW VERSUS THE PAMPAS MATERIAL HISTORY AN EASY PASSAGE Patience Agbabi GRASS Ros Barber John Burnside Julia Copus Simon Armitage This poem looks at the idea of a This poem considers the relationship This poem considers the transition be- This poem considers the significance of This poem centres around the journey ‘feeder’ role within a relationship, between man made, physical objects, tween childhood and adulthood, and historical events, particularly the World of a young girl sneaking into her house, using an unusual structure of tercet with nature and the natural world, spe- the narrator’s nostalgia for a less con- Trade Center attacks in September presented in a surreal format which stanzas and a notable semantic cifically using the symbolism of a chain- sumer-driven world through the de- 2001. Burnside is a Scottish poet, born helps to create a distinctive narrative field. Agbabi is a performance poet saw to show man’s interaction. scription of a traditional handker- in 1955 in Fife. -

Barbarian Masquerade a Reading of the Poetry of Tony Harrison And

1 Barbarian Masquerade A Reading of the Poetry of Tony Harrison and Simon Armitage Christian James Taylor Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of English August 2015 2 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation fro m the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement The right of Christian James Taylor to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2015 The University of Leeds and Christian James Taylor 3 Acknowledgements The author hereby acknowledges the support and guidance of Dr Fiona Becket and Professor John Whale, without whose candour, humour and patience this thesis would not have been possible. This thesis is d edicat ed to my wife, Emma Louise, and to my child ren, James Byron and Amy Sophia . Additional thanks for a lifetime of love and encouragement go to my mother, Muriel – ‘ never indifferent ’. 4 Abstract This thesis investigates Simon Armitage ’ s claim that his poetry inherits from Tony Harrison ’ s work an interest in the politics o f form and language, and argues that both poets , although rarely compared, produce work which is conceptually and ideologically interrelated : principally by their adoption of a n ‘ un - poetic ’ , deli berately antagonistic language which is used to invade historically validated and culturally prestigious lyric forms as part of a critique of canons of taste and normative concepts of poetic register which I call barbarian masquerade . -

2018 Forward Prizes for Poetry Announce “Urgent, Engaged and Inspirational” Shortlists

MEDIA RELEASE | IMMEDIATE RELEASE, THURSDAY 24 MAY 2018 2018 FORWARD PRIZES FOR POETRY ANNOUNCE “URGENT, ENGAGED AND INSPIRATIONAL” SHORTLISTS Nuclear stand-off, new-born lambs, sex, Hollywood blockbusters, and addiction - Britain’s most coveted poetry awards, the Forward Prizes for Poetry, have today announced shortlists dominated by “urgent, engaged and inspirational” voices tackling complex subjects with brio. The chair of the 2018 jury, the writer, critic and broadcaster Bidisha, said: “In reading for this year’s Forward Prizes, the other judges and I discovered an art form that is in roaring health. We read countless collections full of wonder and possibility, light but not trivial, serious but not depressing, lushly emotional but not sentimental, frequently witty and capable of great craft and zingy modernity. “Our shortlists represent the stunning variety and breadth of poetry today, with contemporary international voices that are urgent, engaged and inspirational.” The Forward Prizes for Poetry celebrate the best new poetry published in the British Isles. They honour both established poets and emerging writers with three distinct awards: Best Collection, Best First Collection and Best Single Poem. They are sponsored by Bookmark Content, the content and communications company. The 2018 Forward Prize for Best Collection (£10,000) Vahni Capildeo – Venus as a Bear (Carcanet) Toby Martinez de las Rivas – Black Sun (Faber) J.O. Morgan – Assurances (Cape) Danez Smith – Don’t Call Us Dead (Chatto) Tracy K. Smith – Wade in the Water (Penguin) -

Mapping and Twentieth-Century American Poetry

The Dissertation Committee for Alba Rebecca Newmann certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “Language is not a vague province”: Mapping and Twentieth -Century American Poetry Committee: ________________________ ______ Wayne Lesser, Supervisor ______________________________ Thomas Cable, Co -Supervisor ______________________________ Brian Bremen ______________________________ Mia Carter ______________________________ Nichole Wiedemann “Language is not a vague province”: Mapping and Twentieth -Century American Poetry by Alba Rebecca Newmann, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2006 Acknowledgements I wish to express my appreciation to each of my dissertation committee members, Wayne, Tom, Mia, Brian, and Nichole, for their insight and encouragement throughout the writing of this document. My family has my heartfelt thanks as well , for their unflagging support in this, and all my endeavors. To my lovely friends and colleagues at the University of Texas —I am grateful to have found myself in such a vibrant and collegial community ; it surely facilitated my completion of this project . And, finally, to The Flightpath, without which, many things would be different. iii “Language is not a vague province”: Mapping and Twentieth -Century American Poetry Publication No. _________ Alba Rebecca Newmann, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2006 Supervisors: Wayne Lesser and Thomas Cable In recent years, the terms “mapping” and “cartography” have been used with increasing frequency to describe literature engaged with place. The limitation of much of this scholarship its failure to investigate how maps themselves operate —how they establish relationships and organize knowledge. -

Incorporating Writing Issue 1 Volume 4 Contact [email protected] ------Incorporating Writing Is an Imprint of the Incwriters Society (UK)

1 www.incwriters.com Incorporating Writing Issue 1 Volume 4 Contact [email protected] ---------------------------------------------------- Incorporating Writing is an imprint of The Incwriters Society (UK). The magazine is managed by an editorial team independent of The Society's Constitution. Nothing in this magazine may be reproduced in whole or part without permission of the publishers. We cannot accept responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts, reproduction of articles, photographs or content. Incorporating Writing has endeavoured to ensure that all information inside the magazine is correct, however prices and details are subject to change. Individual contributors indemnify Incorporating Writing, The Incwriters Society (UK) against copyright claims, monetary claims, tax payments / NI contributions, or any other claims. This magazine is produced in the UK © The Incwriters Society (UK) 2004 ---------------------------------------------------- In this issue: Editorial: Beginnings and Endings Making Snow Angels With Michael: An Interview with Eva Salzman Interview with Ian Rankin Taking the Leap: An interview with Lucy English Moving Up The Bench Alien: Life in Asia The Screaming Rock - A poetry project for Ireland (and me) Making Connections – thoughts of a literary magazine editor Be Judged or Be Damned Day in the life of a guidebook writer She is Reviews ---------------------------------------------------- Beginnings and Endings Editorial by Andrew Oldham The Incwriters Society (UK) is passing into a new phase, with plans to open a chapter in the States in 2005 and bring grass roots promotion and poetry to wider audience, our reach now extends across several continents; projects include the sponsoring of the poet, Dave Wood, in his recent Ireland trip (see the new regular column in this edition) and bringing the Suffolk County (NY) Poet Laureate, George Wallace to the UK this November, part of his wider USA and European tour (see George's latest article). -

Poetry in Performance: Intertextuality, Intra

POETRY IN PERFORMANCE: INTERTEXTUALITY, INTRA-TEXTUALITY, POECLECTICS This paper builds on a presentation given by the author at the NAWE Conference on Re-Writing, 25 November 2000 at Oxford Brookes University, where the main ideas were aired. A more complete treatment ensued at the 3rd Research Colloquium: “The Politics of Presence: Re-Reading the Writing Subject in ‘Live’ and Electronic Performance, Theatre and Film Poetry”; held at the Research Centre for Modern and Contemporary Poetry, Oxford Brookes University, 2-3 April 2001. © Mario Petrucci, 2000 / 2001. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract From fable to historical fact, Intertextuality has been for me - as for many contemporary writers - a potent driving force behind my creativity, an ongoing interest running deeper than the pleasures and subversions of, say, pastiche, parody or travesty. I present here an eclectic conception of writing which I term ‘Poeclectics’. Coined at first to reflect certain types of diversification among British poets on the page, I now see it has parallel applications for ‘performative’ works, as well as into and beyond other textual genres. Poeclectics is a re-orientation towards Re- Writing that re-emphasises the conventional re-visitation of literature’s more recognisable ‘voices’; but it can also quarry, in innovative ways, various elements of the experimental/ avant-garde, so as to encompass a variety of other processes and disciplines - anything from geology to mutagenics. Here, I position the term relative to several authors who observe similar patterns of development in British poetry since the Movement. In addition, I negotiate the positive (and negative) roles for Poeclectics as praxis - not only towards page-work but also as a support and spur for site-specific (‘situational’) writing and public commissions, modes of writing I describe as ‘performance poems without a performer’. -

How to Explain This and the Construction Of

How to Explain This and The Construction of Disability in British Female Poetry in the 1990s-2010s: How Susan Wicks and Jo Shapcott Typify the New Generation’s Attention to Body and Difference A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Eleanor C. Ward School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 4 Declaration ............................................................................................................................... 5 Copyright .................................................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... 6 How to Explain This ................................................................................................................. 7 Part I. .................................................................................................................................... 8 2013 - Three-Hundred Afternoons at the Neurology Hospital ........................................ 8 2016 - Three-Hundred Days to Explain .......................................................................... 18 2016-2017 Three-Hundred Days Outside the Neurology Hospital ................................ 21 Part II. ................................................................................................................................ -

Touching the Untouchable: the Language of Touch in the Poetry of Michael Symmons Roberts

TOUCHING THE UNTOUCHABLE: THE LANGUAGE OF TOUCH IN THE POETRY OF MICHAEL SYMMONS ROBERTS MARTIN ULRICH KRATZ PhD 2016 TOUCHING THE UNTOUCHABLE: THE LANGUAGE OF TOUCH IN THE POETRY OF MICHAEL SYMMONS ROBERTS MARTIN ULRICH KRATZ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English, Manchester Metropolitan University 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 ABSTRACT 4 NOTES AND ABBREVIATIONS 5 INTRODUCTION 7 Methodology: The Language of Touch 12 Critical Discourse on the Poetry of Michael Symmons Roberts 25 Chapter Breakdown 35 CHAPTER 1: FIGURING THE TOUCHABLE AND THE UNTOUCHABLE 42 Shell and Spark: Tactile Realism and Symbolism in Incarnational Poetics 48 Machine and Ghost: Negotiating Cartesian Dualism in Drysalter (2013) 73 Body and Soul: Writing into the Gaps Between the Corporeal and Spiritual 101 CHAPTER 2: EXPOSING THE LIMITS AND EDGES OF TOUCH 122 Twenty-first-Century Metaphysical Poetry: At the Limit of the Conceit 125 Between Spaces: Blurring Edges in ‘Edgelands’ 155 1 CHAPTER 3: ‘HOW TO TOUCH UPON THE UNTOUCHABLE’ — FOUR CASE STUDIES 173 ‘Voice-prints’: Lyric Touch in ‘Last Words’ (2002) 177 Caring: Touching the Dead and the Corpse Poem in Corpus (2003) 200 Contamination: Cold War Poetics in Burning Babylon (2001) 218 ‘Metaxu’: Simone Weil’s Touch in Soft Keys (1993) 251 CONCLUSION 274 BIBLIOGRAPHY 285 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the AHRC for the generous studentship that allowed me to complete this project; my supervisors Angelica Michelis and Nikolai Duffy for their patience, forbearing and support over the past three years; everyone at the Graduate School and the Faculty of Humanities, Languages and Social Science who has been involved with the project from the interview stage to its submission; and Deborah Bown, because she knows everything and helps everyone. -

Conference Programme

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 3RD CONTEMPORARY BRITISH AND IRISH POETRY CONFERENCE, UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER September 12-14th 2013 THURSDAY 12 SEPTEMBER 11AM-12: Keynote 1: Don Paterson , ‘New Tropes in Contemporary Poetry – A Theoretical Approach’ 12-1:15 Session 1a Reconstructions Ian Pople, University of Manchester Roy Fisher’s The Ship’s Orchestra: Groovy or Gooey? Kym Martindale, Falmouth University Mourning Becomes Us – The Shrine Re-Membered in Alice Oswald’s Memorial and Paul Muldoon’s Maggot Jonathan Ellis, University of Sheffield ‘Don’t be afraid, old son’: Michael Donaghy’s Elegies Session 1b Scotland Scott Brewster, University of Salford John Burnside: Writing, Wilderness, Withdrawal Garry Mackenzie, University of St Andrews Utopias, Miniature Worlds and Global Networks in Modern Scottish Island Poetry Louise Chamberlain, University of Nottingham ‘Revealing-concealing’ in Thomas A. Clark’s The Hundred Thousand Places Session 1c Mapping Belfast Jessika Köhler, University of Hamburg, Germany Re-reading Belfast – The City in Recent Poetry Margaret Mills Harper, University of Limerick Poetic Devices and Square Windows: Sinead Morrissey's Spatial Ethics Ciaran O'Neill, Queen's University Belfast Ciaran Carson and Edward Thomas: Landscape, Memory, Influence. LUNCH 1:15-2:15 2:15-3:30 Session 2a Place & Space Alice Entwistle, University of Glamorgan ‘Forms of Address’: reading/writing topos, topography and topology in the poetries of contemporary Wales Niamh Downing, Falmouth University “Lens grinders in space”: Literary Geographies of the -

The Place for Poetry 2015-Full Programme

The Place for Poetry Goldsmiths Writers’ Centre Goldsmiths, University of London 7th – 8th May 2015 This dynamic two-day festival will investigate the spaces in which contemporary poetry operates. Through a programme of seminars, readings and academic papers from leading poets and poetic practitioners, we aim to explore the place of, as well as the spaces for poetry in modern life. From war reporting to mappings of migration, from defining individual identity to relating stories of community, contemporary poets take on huge themes. Yet what space does poetry occupy? What tasks can it perform? How is poetry used to negotiate the three-dimensional world? Where do we locate the impulse towards the experiential, the political and the experimental in contemporary poetry? How does poetry accommodate language shifts – especially urban languages? What are the fertile areas for growth and publication in poetry? Table of Contents Programme at a glance .................................................................................................................................... 1 WEDNESDAY 6TH MAY READING: What Do You Mean, “Ocean”? 6.30 p.m. .................................................................................. 2 THURSDAY 7th MAY 1 Panel Session One: 10.30 a.m.-12.00 p.m. ............................................................................................. 2 1.1 Panel Title: Fragment & Process .................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Panel Title: Polyphonies