The Ecology of Charophyte Algae (Charales)1 Maximiliano Barbosa, Forrest Lefler, David E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

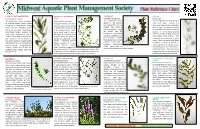

Red Names=Invasive Species Green Names=Native Species

CURLY-LEAF PONDWEED EURASIAN WATERMIL- FANWORT CHARA (Potamogeton crispus) FOIL (Cabomba caroliniana) (Chara spp.) This undesirable exotic, also known (Myriophyllum spicatum) This submerged exotic Chara is typically found growing in species is not common as Crisp Pondweed, bears a waxy An aggressive plant, this exotic clear, hard water. Lacking true but management tools are cuticle on its upper leaves making milfoil can grow nearly 10 feet stems and leaves, Chara is actually a limited. Very similar to them stiff and somewhat brittle. in length forming dense mats form of algae. It’s stems are hollow aquarium species. Leaves The leaves have been described as at the waters surface. Grow- with leaf-like structures in a whorled are divided into fine resembling lasagna noodles, but ing in muck, sand, or rock, it pattern. It may be found growing branches in a fan-like ap- upon close inspection a row of has become a nuisance plant with tiny, orange fruiting bodies on pearance, opposite struc- “teeth” can be seen to line the mar- in many lakes and ponds by the branches called akinetes. Thick ture, spanning 2 inches. gins. Growing in dense mats near quickly outcompeting native masses of Chara can form in some Floating leaves are small, the water’s surface, it outcompetes species. Identifying features areas. Often confused with Starry diamond shape with a native plants for sun and space very include a pattern of 4 leaves stonewort, Coontail or Milfoils, it emergent white/pinkish early in spring. By midsummer, whorled around a hollow can be identified by a gritty texture flower. -

Spirogyra and Mougeotia Zornitza G

Volatile Components of the Freshwater AlgaeSpirogyra and Mougeotia Zornitza G. Kamenarska3, Stefka D. Dimitrova-Konaklievab, Christina Nikolovac, Athanas II. Kujumgievd, Kamen L. Stefanov3, Simeon S. Popov3 * a Institute of Organic Chemistry with Centre of Phytochemistry. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia 1113. Bulgaria. Fax: ++3592/700225. E-mail: [email protected] b Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University, Sofia 1000, Bulgaria c Institute of Soil Sciences and Agroecology, “N. Pushkarov”, Sofia 1080, Bulgaria d Institute of Microbiology, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia 1113, Bulgaria * Author for correspondence and reprint requests Z. Naturforsch. 55c, 495-499 (2000); received February 4/March 13, 2000 Antibacterial Activity, Mougeotia, Spirogyra, Volatile Compounds Several species of freshwater green algae belonging to the order ZygnematalesSpirogyra ( crassa (Ktz.) Czurda, S. longata (Vauch.) Ktz., and Mougeotia viridis (Ktz.) Wittr.) were found to have a specific composition of the volatile fraction, which confirms an earlier pro posal for the existence of two groups in the genusSpirogyra. Antibacterial activity was found in volatiles from S. longata. Introduction and Hentschel, 1966). Tannins (Nishizawa et al., 1985; Nakabayashi and Hada, 1954) and fatty acids While the chemical composition and biological (Pettko and Szotyori, 1967) were also found in activity of marine algae have been studied in Spyrogyra sp. Evidently, research on chemical depth, freshwater algae have been investigated composition of Spirogyra and Mougeotia species less intensively, especially those belonging to Zyg- is very limited, especially on their secondary me nemaceae (order Zygnematales). The most nu tabolites, which often possess biological activity. merous representatives of this family in the Bul The volatile constituents of Zygnemaceae algae garian flora are generaSpirogyra, Mougeotia and are of interest, because such compounds often Zygnema, which inhabit rivers and ponds. -

Bioone? RESEARCH

RESEARCH BioOne? EVOLVED Proximate Nutrient Analyses of Four Species of Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Consumed by Florida Manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) Compared to Romaine Lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. longifolia) Author(s): Jessica L. Siegal-Willott, D.V.M., Dipl. A.C.Z.M., Kendal Harr, D.V.M., M.S., Dipl. A.C.V.P., Lee-Ann C. Hayek, Ph.D., Karen C. Scott, Ph.D., Trevor Gerlach, B.S., Paul Sirois, M.S., Mike Renter, B.S., David W. Crewz, M.S., and Richard C. Hill, M.A., Vet.M.B., Ph.D., M.R.C.V.S. Source: Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 41(4):594-602. 2010. Published By: American Association of Zoo Veterinarians DOI: 10.1638/2009-0118.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1638/2009-0118.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne's Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms of use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. -

The Chloroplast Rpl23 Gene Cluster of Spirogyra Maxima (Charophyceae) Shares Many Similarities with the Angiosperm Rpl23 Operon

Algae Volume 17(1): 59-68, 2002 The Chloroplast rpl23 Gene Cluster of Spirogyra maxima (Charophyceae) Shares Many Similarities with the Angiosperm rpl23 Operon Jungho Lee* and James R. Manhart Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, 77843-3258, U.S.A. A phylogenetic affinity between charophytes and embryophytes (land plants) has been explained by a few chloro- plast genomic characters including gene and intron (Manhart and Palmer 1990; Baldauf et al. 1990; Lew and Manhart 1993). Here we show that a charophyte, Spirogyra maxima, has the largest operon of angiosperm chloroplast genomes, rpl23 operon (trnI-rpl23-rpl2-rps19-rpl22-rps3-rpl16-rpl14-rps8-infA-rpl36-rps11-rpoA) containing both embryophyte introns, rpl16.i and rpl2.i. The rpl23 gene cluster of Spirogyra contains a distinct eubacterial promoter sequence upstream of rpl23, which is the first gene of the green algal rpl23 gene cluster. This sequence is completely absent in angiosperms but is present in non-flowering plants. The results imply that, in the rpl23 gene cluster, early charophytes had at least two promoters, one upstream of trnI and another upstream of rpl23, which partially or completely lost its function in land plants. A comparison of gene clusters of prokaryotes, algal chloroplast DNAs and land plant cpDNAs indicated a loss of numerous genes in chlorophyll a+b eukaryotes. A phylogenetic analysis using presence/absence of genes and introns as characters produced trees with a strongly supported clade contain- ing chlorophyll a+b eukaryotes. Spirogyra and embryophytes formed a clade characterized by the loss of rpl5 and rps9 and the gain of trnI (CAU) and introns in rpl2 and rpl16. -

Seed Plant Models

Review Tansley insight Why we need more non-seed plant models Author for correspondence: Stefan A. Rensing1,2 Stefan A. Rensing 1 2 Tel: +49 6421 28 21940 Faculty of Biology, University of Marburg, Karl-von-Frisch-Str. 8, 35043 Marburg, Germany; BIOSS Biological Signalling Studies, Email: stefan.rensing@biologie. University of Freiburg, Sch€anzlestraße 18, 79104 Freiburg, Germany uni-marburg.de Received: 30 October 2016 Accepted: 18 December 2016 Contents Summary 1 V. What do we need? 4 I. Introduction 1 VI. Conclusions 5 II. Evo-devo: inference of how plants evolved 2 Acknowledgements 5 III. We need more diversity 2 References 5 IV. Genomes are necessary, but not sufficient 3 Summary New Phytologist (2017) Out of a hundred sequenced and published land plant genomes, four are not of flowering plants. doi: 10.1111/nph.14464 This severely skewed taxonomic sampling hinders our comprehension of land plant evolution at large. Moreover, most genetically accessible model species are flowering plants as well. If we are Key words: Charophyta, evolution, fern, to gain a deeper understanding of how plants evolved and still evolve, and which of their hornwort, liverwort, moss, Streptophyta. developmental patterns are ancestral or derived, we need to study a more diverse set of plants. Here, I thus argue that we need to sequence genomes of so far neglected lineages, and that we need to develop more non-seed plant model species. revealed much, the exact branching order and evolution of the I. Introduction nonbilaterian lineages is still disputed (Lanna, 2015). Research on animals has for a long time relied on a number of The first (small) plant genome to be sequenced was of THE traditional model organisms, such as mouse, fruit fly, zebrafish or model plant, the weed Arabidopsis thaliana (c. -

Anders Langangen Charophytes (Charales) from Samos and Ikaria (Greece) Collected in 2013 and Report on Some Localities in Skiath

Fl. Medit. 24: 139-151 doi: 10.7320/FlMedit24.139 Version of Record published online on 30 December 2014 Anders Langangen Charophytes (Charales) from Samos and Ikaria (Greece) collected in 2013 and report on some localities in Skiathos (Greece) Abstract Langangen, A.: Charophytes (Charales) from Samos and Ikaria (Greece) collected in 2013 and report on some localities in Skiathos (Greece). — Fl. Medit. 24: 139-151. 2014. — ISSN: 1120- 4052 printed, 2240-4538 online. In 2013 three Greek islands, Samos, Ikaria and Skiathos were visited. Charophytes were found in Samos and Ikaria but not in Skiathos. Out of 23 visited localities charophytes were found in 12. Seven species of charophytes were found in Samos (Lamprothamnium papulosum, Chara canescens, C. vul- garis, C. gymnophylla, C. corfuensis, Tolypella nidifica and T. glomereta) and in Ikaria one species (Chara vulgaris). Species richness in Samos is due to a variety of different habitats including brack- ish water lakes, running brackish water, fresh water pools and slowly moving rivers. Key words: Tolypella nidifica, T. glomerata, Lamprothamnium papulosum, Chara canescens, C, vulgaris, C. gymnophylla, C. corfuensis. Introduction Samos and Ikaria are the two southernmost islands of the Northeast Agean Islands. Several water bodies including lakes, reservoirs, brackish water, brooks and springs were visited. Localities with charophytes are listed in Table 1 and localities without charophytes in Table 2. Skiathos, an island in the Northern Sporades, where no charophytes were found, was also visited. Materials and methods This work is based on material collected in the localities on Samos and Ikaria in May (Fig. 1) and Skiathos in September 2013. -

Plant Evolution an Introduction to the History of Life

Plant Evolution An Introduction to the History of Life KARL J. NIKLAS The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 1 Origins and Early Events 29 2 The Invasion of Land and Air 93 3 Population Genetics, Adaptation, and Evolution 153 4 Development and Evolution 217 5 Speciation and Microevolution 271 6 Macroevolution 325 7 The Evolution of Multicellularity 377 8 Biophysics and Evolution 431 9 Ecology and Evolution 483 Glossary 537 Index 547 v Introduction The unpredictable and the predetermined unfold together to make everything the way it is. It’s how nature creates itself, on every scale, the snowflake and the snowstorm. — TOM STOPPARD, Arcadia, Act 1, Scene 4 (1993) Much has been written about evolution from the perspective of the history and biology of animals, but significantly less has been writ- ten about the evolutionary biology of plants. Zoocentricism in the biological literature is understandable to some extent because we are after all animals and not plants and because our self- interest is not entirely egotistical, since no biologist can deny the fact that animals have played significant and important roles as the actors on the stage of evolution come and go. The nearly romantic fascination with di- nosaurs and what caused their extinction is understandable, even though we should be equally fascinated with the monarchs of the Carboniferous, the tree lycopods and calamites, and with what caused their extinction (fig. 0.1). Yet, it must be understood that plants are as fascinating as animals, and that they are just as important to the study of biology in general and to understanding evolutionary theory in particular. -

Introduction to Common Native & Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska

Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska Cover photographs by (top to bottom, left to right): Tara Chestnut/Hannah E. Anderson, Jamie Fenneman, Vanessa Morgan, Dana Visalli, Jamie Fenneman, Lynda K. Moore and Denny Lassuy. Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska This document is based on An Aquatic Plant Identification Manual for Washington’s Freshwater Plants, which was modified with permission from the Washington State Department of Ecology, by the Center for Lakes and Reservoirs at Portland State University for Alaska Department of Fish and Game US Fish & Wildlife Service - Coastal Program US Fish & Wildlife Service - Aquatic Invasive Species Program December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................ x Introduction Overview ............................................................................. xvi How to Use This Manual .................................................... xvi Categories of Special Interest Imperiled, Rare and Uncommon Aquatic Species ..................... xx Indigenous Peoples Use of Aquatic Plants .............................. xxi Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts ................................................................................. xxi Vectors ................................................................................. xxii Prevention Tips .................................................... xxii Early Detection and Reporting -

Anders Langangen Charophytes (Charales) from Crete (Greece) Collected in 2010

Fl. Medit. 22: 25-32 doi: 10.7320/FlMedit22.025 Version of Record published online on 28 December 2012 Anders Langangen Charophytes (Charales) from Crete (Greece) collected in 2010 Abstract Langangen, A.: Charophytes (Charales) from Crete (Greece) collected in 2010. — Fl. Medit. 22: 25-32. 2012. — ISSN: 1120-4052 printed, 2240-4538 online. In this article charophytes are reported from the island of Crete, the largest island in Greece. On 9 visited localities, charophytes have been found in six. All localities, except one (loc. 6) are freshwater. Totally six different species were found: Chara aspera, C. connivens, C. corfuen- sis, C. vulgaris, Nitella hyalina and N. tenuissima. The most interesting locality is Lake Kournas which is an eutrophic Chara-lake with rich vegetation of four species: Chara cor- fuensis, C. aspera and the two species of Nitella. Key words: Crete, Greece, Chara aspera, C. connivens, C. corfuensis, C. vulgaris, Nitella hyali- na, N. tenuissima. Introduction The island of Crete is the largest island in Greece and is situated in the southernmost part of the country. I visited several water bodies, lakes, reservoirs and seasonally wet meadows. The localities are listed in Table 1, and of nine, charophytes were found in six. Charophytes have earlier been reported from Crete in several works e.g. Corillion (1957), Koumpli-Sovantzi (1997), Bergmeister & Abrahamczyk (2008). Materials and methods This work is based on material collected in Crete (Greece) in the given localities in 2010 (Fig. 1). The specific conductivity of the water was measured with a Milwaukee, SM 301 EC meter, range 0-1990 µm/cm. -

Starry Stonewort

Nitellopsis obtusa Starry Stonewort A Non-Native Submerged Aquatic Lower Plant STARRY STONEWORT (SSW) Nitellopsis obtusa General Characteristics The “squeeze test” may be used to distinguish SSW from Chara spp. • In SSW, the protoplasm will pop out of the cell when squeezed. The remaining cell wall becomes limp straw (G. Douglas Pullman, Aquest Corp, personal communication). • In Chara spp., the protoplasm does not separate easily from Source: Online photo. www.startribune.com. the cell wall (Hackett et al. MI Dept. Environ. Quality. Chara sp., a native 2014). lake weed on left; SSW on right. STARRY STONEWORT (SSW) Nitellopsis obtusa General Characteristics • SSW plants can form gyrogonites, which are calcified, spiral-shaped fructifications (Bharathan 1983, 1987). • Many Charophytes produce lime-shells around their oospores, & these lime-shells (called gyrogonites) are frequently found as fossils. (See www.charophytes.com/cms/index.php?option=com_con tent&view=article&id). STARRY STONEWORT (SSW) Nitellopsis obtusa General Characteristics SEM lateral & apical views of gyrogonites of : • Chara aspera (figs.1-2); • C. hispida (figs. 3-4); • C. globularis (figs. 5-6) Source:www.researchg ate.net STARRY STONEWORT (SSW) Taxonomic Classification • EMPIRE……………………………………………...Eukaryota • KINGDOM.…………………………………………. Protista • PHYLUM…………………………………………..Charophyta • CLASS ……………………………………….……Charophyceae • ORDER………………………………………………Charales • FAMILY………………………………………………Characeae • GENUS……………………………………………….Nitellopsis* • SPECIES……………………………………………..obtusa *Other genera in the Characeae family include Chara, Lamprothamnium, Lynchnothamnus, Nitella, & Tolypella. Source: Lewis & McCount (2004). STARRY STONEWORT (SSW) Taxonomic Classification Starry stonewort description Stoneworts used to be classified as members of the plant kingdom, but it is now agreed that they belong – along with other green algae – in the kingdom Protista. Put simply, the protistas are simple multi-celled or single celled organisms, descended from some of the earliest life- forms that appeared on Earth. -

The Origin of Alternation of Generations in Land Plants

Theoriginof alternation of generations inlandplants: afocuson matrotrophy andhexose transport Linda K.E.Graham and LeeW .Wilcox Department of Botany,University of Wisconsin, 430Lincoln Drive, Madison,WI 53706, USA (lkgraham@facsta¡.wisc .edu ) Alifehistory involving alternation of two developmentally associated, multicellular generations (sporophyteand gametophyte) is anautapomorphy of embryophytes (bryophytes + vascularplants) . Microfossil dataindicate that Mid ^Late Ordovicianland plants possessed such alifecycle, and that the originof alternationof generationspreceded this date.Molecular phylogenetic data unambiguously relate charophyceangreen algae to the ancestryof monophyletic embryophytes, and identify bryophytes as early-divergentland plants. Comparison of reproduction in charophyceans and bryophytes suggests that the followingstages occurredduring evolutionary origin of embryophytic alternation of generations: (i) originof oogamy;(ii) retention ofeggsand zygotes on the parentalthallus; (iii) originof matrotrophy (regulatedtransfer ofnutritional and morphogenetic solutes fromparental cells tothe nextgeneration); (iv)origin of a multicellularsporophyte generation ;and(v) origin of non-£ agellate, walled spores. Oogamy,egg/zygoteretention andmatrotrophy characterize at least some moderncharophyceans, and arepostulated to represent pre-adaptativefeatures inherited byembryophytes from ancestral charophyceans.Matrotrophy is hypothesizedto have preceded originof the multicellularsporophytes of plants,and to represent acritical innovation.Molecular -

Floristic Survey of Algae in Some Freshwater Habitats of Kohima District, Nagaland (India)

Journal of Advanced Plant Sciences 2021.11(1): 60-73 60 RESEARCH ARTICLE Floristic survey of Algae in some freshwater habitats of Kohima District, Nagaland (India) Keviphruonuo Kuotsu* and S. K. Chaturvedi Department of Botany, Nagaland University, Lumami-798627, Nagaland, India Received: 20 November 2020 / Revised: 12 April 2021 / Accepted: 30 April 2021 © Botanical Society of Assam 2021 blue green algae (Oinam et al.,2010, Devi et al., Abstract 2010) were reported from Nagaland. Studies was also done from the fresh water bodies (lakes, ponds The present paper deals with the algal flora study of streams and rivers) of Dimapur, Chumukedima, Kohima District, Nagaland, which is located Peren and Wokha districts, 94 algal taxa were between 25024’N - 25099’. N latitude and 94001’E - 0 reported (Das and Adhikary 2012). 94 29 E longitude with an average elevation of 1261m and an area of 1,595 sq. km. In the present Kohima district is the capital of Nagaland with an study, 40 algal taxa were reported where 5 algal taxa area of 1463 sq km and located between 25024’N - belongs to Class Cyanophyceae, 5 algal taxa belongs 25099’N latitude and 94001’E - 94029’E longitude to Class Chlorophyceae, 19 algal taxa belongs to with an average elevation of 1261 m. Algal work on Class Bacilariophyceae, 1 algal taxa belongs to Kohima District has not been reported by any Class Coscinodiscophyceae, 2 algal taxa belongs to workers and so the present study has been carried Class Ulvophyceae and 8 algal taxa belongs to Class out to study the flora and resources of algae on some Zygnematophyceae.