Devres, Inc. 2426 Ontario Road, N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

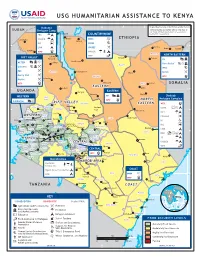

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Kenya

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO KENYA 35° 36° 37° 38° 39° 40°Original Map Courtesy 41° of the UN Cartographic Section 42° SUDAN The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance Todenyang COUNTRYWIDE by the U.S. Government. Banya ETHIOPIA Lokichokio KRCS Sabarei a UNICEF 4° F 4° RIFT VALLEY Banissa WFP Ramu Mandera ACTED Kakuma ACRJ Lokwa UNHCR Kangole p ManderaMandera Concern CF Moyale Takaba IFRC North Horr Lodwar IMC F MoyaleMoyale 3° El NORTHWak EASTERN 3° Merlin F Loiyangalani FH FilmAid TurkanaTurkana Buna AC IRC MarsabitMarsabit Mercy USA F J j D Lokichar JRS k WASDA J j Marsabit WajirWajir Tarbaj CARE LWR ikp EASTERNEASTERN Vj J 2° Girito Salesian Missions Lokori Center for 2° S Victims of Torture k Baragoi EASTERN World University Laisamis Wajir of Canada V FH FilmAid WestWest AC PokotPokot NORTHNORTH Handicap Int. RIFTR I F T VALLEYVA L L E Y SamburuSamburu EASTERNEASTERN IRC UGANDA Tot j D Maralal TransTrans NzoiaNzoia MarakwetMarakwet Archer's LWR 1° MtMt Kitale BaringoBaringo Dif ikp 1° Kisima Post Habaswein ElgonElgon NRC LugariLugari Lorule S I WESTERNWESTERN UasinUasin SC BungomaBungoma GishuGishu Mado Gashi G TesoTeso Marigat IsioloIsiolo Busia Webuye Eldoret KeiyoKeiyo Isiolo World UniversityLiboi KakamegaKakamega Lare Kinna of Canada V Burnt Nyahururu LaikipiaLaikipia BusiaBusia Kakamega Forest Butere NandiNandi KoibatekKoibatek (Thomson's Falls) MeruMeru NorthNorth Nanyuki Dadaab SiayaSiaya VihigaVihiga Subukia Mogotio Meru 0° Kipkelion MeruMeru 0° Londiani a KisumuKisumu -

SOLAR FREEZE Republic of Kenya

SOLAR FREEZE Republic of Kenya Equator Initiative Case Studies Local sustainable development solutions for people, nature, and resilient communities UNDP EQUATOR INITIATIVE CASE STUDY SERIES Local and Indigenous communities across the world are solutions (NBS) for climate change and local sustainable advancing innovative sustainable development solutions development. Selected from 847 nominations from across that work for people and for nature. Few publications 127 countries, the winners were celebrated at a gala event or case studies tell the full story of how such initiatives in New York, coinciding with UN Climate Week and the evolve, the breadth of their impacts, or how they change 74th Session of the UN General Assembly. The winners are over time. Fewer still have undertaken to tell these stories sustainably protecting, restoring, and managing forests, with community practitioners themselves guiding the farms, wetlands, and marine ecosystems to mitigate narrative. The Equator Initiative aims to fill that gap. greenhouse gas emissions, help communities adapt to The Equator Initiative, supported by generous funding from climate change, and create a green new economy. Since the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation 2002, the Equator Prize has been awarded to 245 initiatives and Development (BMZ) and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), awarded the The following case study is one in a growing series that Equator Prize 2019 to 22 outstanding local community describes vetted and peer-reviewed best practices and Indigenous peoples initiatives from 16 countries. Each intended to inspire the policy dialogue needed to of the 22 winners represents outstanding community and scale nature-based solutions essential to achieving the Indigenous initiatives that are advancing nature-based Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). -

Geohydrology of Orth Eastern Province

Geohydrology of orth Eastern Province GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-N Prepared in cooperation with the ^ Water Department, Kenya Ministry /%£ of Agriculture under the auspices M^ of the US. Agency for International \v» Development \^s Geohydrology of oEC 2f North Eastern Province, Kenya By W. V. SWARZENSKI and M. J. MUNDORFF CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF AFRICA AND THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-N Prepared in cooperation with the Water Department, Kenya Ministry of Agriculture under the auspices of the U.S. Agency for International Development UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1977 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Swarzenski, Wolfgang Victor, 1917- Geohydrology of North Eastern Province, Kenya. (Geological Survey water-supply paper; 1757-N) Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.13:1757-N 1. Water, Under ground-Kenya--North-Eastern Province. I. Mundorff, Maurice John, 1910- joint author. II. Title. III. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Water-supply paper; 1757-N. TC801.U2 no. 1757-N [GB1173.K4] 553'.7'0973s [553J.79'0967624] 77-608022 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington; D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-02977-4 CONTENTS Page Abstract ______________________________________ Nl Introduction _____________________________________ 2 Purpose and scope of project ____________________ -

Ethnic Violence, Elections and Atrocity Prevention in Kenya

Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect Occasional Paper Series No. 4, December 2013 “ R2P in Practice”: Ethnic Violence, Elections and Atrocity Prevention in Kenya Abdullahi Boru Halakhe The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect was established in February 2008 as a catalyst to promote and apply the norm of the “Responsibility to Protect” populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. Through its programs, events and publications, the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect is a resource and a forum for governments, international institutions and non-governmental organizations on prevention and early action to halt mass atrocity crimes. Acknowledgments: This Occasional Paper was produced with the generous support of the government of the Federal Republic of Germany. About the Author: Abdullahi Boru Halakhe is a security and policy analyst on the Horn of Africa and Great Lakes regions. Abdullahi has represented various organizations as an expert on these regions at the UN and United States State Department, as well as in the international media. He has authored and contributed to numerous policy briefings, reports and articles on conflict and security in East Africa. Previously Abdullahi worked as a Horn of Africa Analyst with International Crisis Group working on security issues facing Kenya and Uganda. As a reporter with the BBC East Africa Bureau, he covered the 2007 election and subsequent violence from inside Kenya. Additionally, he has worked with various international and regional NGOs on security and development issues. Cover Photo: Voters queue to cast their votes on 4 March 2013 in Nakuru, Kenya. -

NATIONAL WILDLIFE CENSUS 2021 REPORT.Pdf

Written and Edited By (Authors): Brig. (Rtd) John Waweru2, Dr. Patrick Omondi1, Dr. Shadrack Ngene1, Dr. Joseph Mukeka1, Edwin Wanyonyi2, Bernard Ngoru1, Stephen Mwiu1, Daniel Muteti1, Fredrick Lala1, Linus Kariuki1, Dr. Festus Ihwagi3, Sospeter Kiambi1, Cedric Khyale1, Geoffrey Bundotich1, Dr. Fred Omengo1, Peter Hongo1, Peter Maina1, Faith Muchiri1, Dr. Mohammed Omar1, Judith Nyunja1, Joseph Edebe1, James Mathenge1, George Anyona1, Chrispin Ngesa1, John Gathua4, Lucy Njino4, Gakami Njenga4, Anthony Wandera5, Samuel Mutisya6, Redempta Njeri7, David Kimanzi8, Titus Imboma9, Jane Wambugu1, Timoth Mwinami9, Ali Kaka10 and Dr. Erustus Kanga10 1Wildlife Research and Training Institute, P.O. Box 842-20117, Naivasha, Kenya 2Kenya Wildlife Service, P.O. Box 409241-00100, Nairobi, Kenya 3Save the elephants, P.O. Box 54667-00200, Nairobi, Kenya 4Directorate of Resource Surveys and Remote Sensing, P.O. Box 47146-00100, Nairobi, Kenya 5Northern Rangeland Trust, Private Bag-60300, Isiolo, Kenya 6Ol Pajeta Conservancy, Private Bag-10400, Nanyuki, Kenya 7Space for Giants, P.O. Box 174-10400, Nanyuki, Kenya 8Mara Elephant Project, P.O. Box 2606-00502, Narok, Kenya 9National Museums of Kenya, P.O. Box 40658-00100, Nairobi, Kenya 10Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife, P.O. Box 30126-00100, Nairobi, Kenya Concept and Design by: Boniface Gor, www.digimatt.co.ke @digimattsol ©Photos: David Macharia/Versatile Photography | David Gotlib | KWS | Shatterstock | Freepik Published in July 2021 by the Wildlife Research and Training Institute (WRTI) and Kenya Wildlife -

USAID/OFDA Kenya Program Map 8/18/2010

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO KENYA 35° Kakuma 36° 37° 38° 39° 40°Original Map Courtesy 41° of the UN Cartographic Section 42° SUDAN The boundaries and names used on this map do Refugee Camp not imply official endorsement or acceptance Todenyang JRS G COUNTRYWIDE by the U.S. Government. Banya ETHIOPIA Lokichokio UNHCR KRCS G Sabarei a IRC OCHA B 4° D 4° LWR UNICEF Banissa F Ramu Mandera Kakuma WFP UNHCR G ManderaMandera NORTH EASTERN Lokwa WFP y RIFT VALLEY Moyale Kangole Takaba FH AC North Horr El Wak ACTED ACJ Lodwar Horn Relief MoyaleMoyale B JC 3° 3° Concern BCF IFRC B IMC F TurkanaTurkana Loiyangalani Buna SC/UK F Mercy USA F MarsabitMarsabit WFP Merlin F Lokichar WFP Marsabit WajirWajir Tarbaj SOMALIA EASTERNEASTERN 2° Lokori Girito 2° UGANDA Baragoi EASTERN Laisamis Wajir FH Dadaab WESTERN WestWest AC PokotPokot NORTHNORTH Refugee Complex Solidarités AJ WFP RIFTR I F T VALLEYVA L L E Y SamburuSamburu EASTERNEASTERN Tot WFP Maralal Dif TransTrans NzoiaNzoia MarakwetMarakwet Archer's CARE J 1° MtMt Kitale BaringoBaringo V 1° Kisima Post Habaswein ElgonElgon CVT LugariLugari Lorule Liboi G UasinUasin WESTERNWESTERN FilmAid BungomaBungoma GishuGishu IsioloIsiolo Mado Gashi D TesoTeso Webuye Eldoret Marigat Busia Isiolo HI KakamegaKakamega KeiyoKeiyo Lare Kinna Burnt Nyahururu LaikipiaLaikipia BusiaBusia Kakamega Forest IRC D Butere NandiNandi KoibatekKoibatek (Thomson's Falls) MeruMeru NorthNorth Nanyuki Dadaab SiayaSiaya VihigaVihiga Subukia Mogotio Meru LWR 0° Kipkelion MeruMeru 0° Londiani a KisumuKisumu Koru CentralCentral -

Mikoko Pamoja (Kenya)

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. MIKOKO PAMOJA Kenya Equator Initiative Case Studies Local sustainable development solutions for people, nature, and resilient communities UNDP EQUATOR INITIATIVE CASE STUDY SERIES Local and indigenous communities across the world are development in marine, forest, grassland, dryland and advancing innovative sustainable development solutions wetland ecosystems. Selected from 806 nominations from that work for people and for nature. Few publications across 120 countries, the winners were celebrated at a gala or case studies tell the full story of how such initiatives event in New York, coinciding with Global Goals Week and evolve, the breadth of their impacts, or how they change the 72nd Session of the UN General Assembly. Special over time. Fewer still have undertaken to tell these stories emphasis was placed on scalable, nature-based solutions with community practitioners themselves guiding the to address biodiversity conservation, climate change narrative. The Equator Initiative aims to fill that gap. adaptation, disaster risk reduction, gender equality, land The Equator Initiative, supported by generous funding rights, and food and water security to reduce poverty, from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation protect nature, and strengthen resilience. (NORAD) and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), awarded the The following case study is one in a growing series that Equator Prize 2017 to 15 outstanding local community describes vetted and peer-reviewed best practices intended and indigenous peoples initiatives from 12 countries. to inspire the policy dialogue needed to scale nature- The winners were recognized for their significant work based solutions essential to achieving the Sustainable to advance nature-based solutions for sustainable Development Goals. -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Kenya

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO KENYA 35° 36° 37° 38° 39° 40°Original Map Courtesy 41° of the UN Cartographic Section 42° SUDAN The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance Todenyang COUNTRYWIDE by the U.S. Government. Banya ETHIOPIA Lokichokio KRCS Sabarei a UNICEF 4° F 4° RIFT VALLEY Banissa WFP Ramu Mandera ACTED Kakuma ACRJ Lokwa UNHCR Kangole p ManderaMandera Concern CF Moyale Takaba IFRC North Horr Lodwar IMC F MoyaleMoyale 3° El NORTHWak EASTERN 3° Merlin F Loiyangalani FH FilmAid TurkanaTurkana Buna AC IRC MarsabitMarsabit Mercy USA F J j D Lokichar JRS k WASDA J j Marsabit WajirWajir Tarbaj CARE LWR ikp EASTERNEASTERN Vj J 2° Girito Salesian Missions Lokori Center for 2° S Victims of Torture k Baragoi EASTERN World University Laisamis Wajir of Canada V FH FilmAid WestWest AC PokotPokot NORTHNORTH Handicap Int. RIFTR I F T VALLEYVA L L E Y SamburuSamburu EASTERNEASTERN IRC UGANDA Tot j D Maralal TransTrans NzoiaNzoia MarakwetMarakwet Archer's LWR 1° MtMt Kitale BaringoBaringo Dif ikp 1° Kisima Post Habaswein ElgonElgon NRC LugariLugari Lorule S I WESTERNWESTERN UasinUasin SC BungomaBungoma GishuGishu Mado Gashi G TesoTeso Marigat IsioloIsiolo Busia Webuye Eldoret KeiyoKeiyo Isiolo World UniversityLiboi KakamegaKakamega Lare Kinna of Canada V Burnt Nyahururu LaikipiaLaikipia BusiaBusia Kakamega Forest Butere NandiNandi KoibatekKoibatek (Thomson's Falls) MeruMeru NorthNorth Nanyuki Dadaab SiayaSiaya VihigaVihiga Subukia Mogotio Meru 0° Kipkelion MeruMeru 0° Londiani a KisumuKisumu -

Groundwater Quality Prediction Using Logistic Regression Model for Garissa County

Africa Journal of Physical Sciences Vol. 3, pp. 13-27, February 2019 http://journals.uonbi.ac.ke/index.php/ajps/index ISSN 2313-3317 I Groundwater Quality Prediction Using Logistic Regression Model for S S Garissa County N 2 1, a,* 2, b 3 George Okoye Krhoda , and Meshack Owira Amimo 1 3 1 Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Nairobi, P.O. Box 30197-00100, Nairobi, - 3 Kenya 3 2Department of Geography, Kenyatta University, P.O. Box 43844-00100, Nairobi, Kenya 1 7 [email protected]*, [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: Groundwater quality modeling can reduce the cost of exploration and Submitted: 18 Jan 2018 siting of boreholes considerably. The present study applies Logistic Accepted: 14 Nov 2018 Regression Model to predict the probability of siting boreholes of fresh Available online: 28 February or saline water based on geospatial data such as altitude (m), 2019 longitudes, latitudes and depths (m), and geophysical data such as electrical resistivity from 45 exploration sites. The geology of the study Keywords: area is represented by permeable water-bearing Tertiary-Quaternary Groundwater sediments located within the Anza Rift. The water bearing zones, or Water quality water struck levels, range in depth between 50 and 150 m and the Prediction average yield of about 1 - 5 m3 per hour, in the case of old wells done Logistic regression model using percussion rigs in the period between 1960s to the 1990s. Recently, the discharge in the wells done using modern mud rotary equipment yields up to 30 m3 per hour, with depths ranging between 200 to 250m below ground level. -

ESIA 1409 Isiolo Garbatulla Garissa Report

0 TINGORI CONSULTANCY LIMITED CERTIFICATE OF DECLARATION AND DOCUMENT AUTHENTICATION This document has been prepared in accordance with Environmental (Impact Assessment and Audit) Regulations, 2003 of the Kenya Gazette supplement No. 56 of 13th June 2003, Legal Notice No. 101. LEAD EIA/AUDIT EXPERTS: THINGURI THOMAS; EIA/AUDIT LICENCE NO. 1889 Signature ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date: ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ FOR: CHINA CAMC ENGINEERING CO., LTD., Signature ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date: ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ PROPONENT: KENYA ELECTRICITY TRANSMISSION CO. LTD NAME: DR. (ENG.) JOSEPH SIROR DESIGNATION: GENERAL MANAGER, TECHNICAL SERVICES Signature-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Do hereby certify that this report was prepared based on the information provided by various stakeholders as well as that collected from other primary and secondary sources and on the best understanding and interpretation of the facts by the Environmental Social & Impact Assessors. It is issued without any préjudice. 1 Environmental & Social Impact Assessment Study Report TINGORI CONSULTANCY LIMITED EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction -

Political Map of Kenya

e 36 37 38 39 40 Guenal 41 42 ° ° Konso ° ° ° ° ° Negele- - Administrative Boundary KENYA 5 5 ° Yabelo ° Houdat D SUDAN Kelem aw Ch'ew Bahir a Lolimi Todenyang ETHIOPI A Banya Lokichokio Sabarei Dolo Odo Sibiloi Mega 4 National Park Banissa 4 ° Ramu ° Kakuma Lake Turkana Mandera Lokwa Kangole Central I.(Lake Rudolf) Kaabong Central Island N. P. Moyale Takaba North Horr Lodwar 3 3 ° l ° e El Wak w k Loiyangalani El Beru Hagia r South I. Marsabit Buna u T South Island National Park Moroto N. P. Lokichar Marsabit UGANDA Girito Tarbaj 2° Lokori 2° South Turkana L. Bisinga Nat. Reser ve Wajir L. Oputa Baragoi m Laisamis a u S NORTH-L aga Losai National B RI F T VAL L E Y EASTERN o Reser ve r Mount Elgon N. P. EASTERN Mbale Maralal Lo Tot Maralal ga Dif SOMALIA Kitale Game o B 1 ir og 1 ° Sanctuary Kisima ' Habaswein a ° Archer's g l Lorule o N Post was L. Baringo E Mado Gashi Tororo WESTERN Shaba Eldoret Nat. Res. Busia Webuye © Nations OnlineKinna Project Liboi Butere Marigat Isiolo ra Nyahururu Bisanadi Lak De (Thomson's Falls) Meru Nat. Rahole Nat. Kakamega L. Bogoria Nanyuki Meru Park Nat. Res. Reser ve Bilis L 0 Solai Mt. Kenya Qooqaani 0 a ° Hagadera ° Londiani 5199 m k Kisumu Aberdares e Nakuru N. P. Mt. Kenya Kora National Tan Nat. Park Reserve a Mfangano North Kitui V NYANZA Molo Nyeri I. Nat. Res. Garissa i Kericho c Gilgil CENTRAL t Kisii Embu o Homa r Naivasha Murang'a Nguni i Bay a L. -

National Marine Ecosystem Diagnostic Analysis (MEDA)

Empowered Lives. Resilient Nations. KENYA © Agostino, StockFreeImages.com © Agostino, National Marine Ecosystem Diagnostic Analysis (MEDA) Agulhas and Somali Current Large Marine Ecosystems (ASCLME) Project ASCLME Agulhas and Somali Current Large Marine Ecosystems Project The GEF unites 182 countries in partnership with international institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the private sector to address global environmental issues while supporting national sustainable development initiatives. Today the GEF is the largest public funder of projects to improve the global environment. An independently operating financial organization, the GEF provides grants for projects related to biodiversity, climate change, international waters, land degradation, the ozone layer, and persistent organic pollutants. Since 1991, GEF has achieved a strong track record with developing countries and countries with economies in transition, providing $9.2 billion in grants and leveraging $40 billion in co-financing for over 2,700 projects in over 168 countries. www.thegef.org UNDP partners with people at all levels of society to help build nations that can withstand crisis, and drive and sustain the kind of growth that improves the quality of life for everyone. On the ground in 177 countries and territories, we offer global perspective and local insight to help empower lives and build resilient nations. www.undp.org The content of this publication was made possible by the UNDP supported GEF Financed Agulhas and Somali Current Large Marine Ecosystems Project, together with significant support from many Kenyan institutions (listed in Acknowledgements) and particularly by the coordinating efforts of the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI), the national focal point institution. This document may be cited as: ASCLME 2012.