Albatross Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Recovery Plan for Threatened Albatrosses and Giant Petrels 2011-2016

National recovery plan for threatened albatrosses and giant petrels 2011-2016 National recovery plan for threatened albatrosses and giant petrels 2011-2016 © Commonwealth Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgment of the sources but no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Strategies Branch Australian Antarctic Division Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities 203 Channel Highway KINGSTON TAS 7050 Citation Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2011), National recovery plan for threatened albatrosses and giant petrels 2011-2016, Commonwealth of Australia, Hobart Acknowledgements This Plan was developed by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) of the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. The AAD is grateful for the support of a wide range of organisations and individuals, who provided valuable information and assistance during the preparation of this Plan. Particular thanks to: - Ms Rachael Alderman and Dr Rosemary Gales from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment, Tasmania; and - Mr Ian Hay, Ms Tara Hewitt, Dr Graham Robertson and Dr Mike Double of the AAD. Cover photograph: Light mantled albatross and chick, North Head, Macquarie Island, 2010; photographer Sarah Way, Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment. i Introduction The first Recovery Plan for albatrosses and giant petrels was released in October 2001 in recognition of the need to develop a co-ordinated conservation strategy for albatrosses and giant petrels listed threatened under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). -

Proposed Development Information to Accompany

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT TO ACCOMPANY DRAFT AMENDMENT NO.6 TO D’ENTRECASTEAUX CHANNEL MARINE FARMING DEVELOPMENT PLAN FEBRUARY 2002 PROPONENT: TASSAL OPERATIONS PTY LTD Glossary ADCP Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler AGD Amoebic Gill Disease ASC Aquaculture Stewardship Council BAP Best Aquaculture Practices BEMP Broadscale Environmental Monitoring Program CAMBA China-Australia Migratory Bird Agreement CEO Chief Executive Officer COBP Code of Best Practice CSER corporate, social and environmental responsibility CSIRO Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation DAFF Depart of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry dBA A-weighted decibels DMB Dry matter basis DO dissolved oxygen DPIW Department of Primary Industries and Water DPIPWE Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and the Environment EDO Environmental Defenders Office ENGOs environmental non-governmental organisations EIS Environmental Impact Statement EMS Environmental Management System EPA Environmental Protection Authority EPBCA Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 FCR Feed Conversion Ratio FHMP Fish Health Management Plan FSANZ Food Standards Australia New Zealand g gram GAA Global Aquaculture Alliance ha hectare HAB Harmful Algal Bloom HOG head on gutted HVN Huon Valley News IALA International Association of Lighthouse Authorities IMAS Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies i JAMBA Japan-Australia Migratory Bird Agreement kg kilogram km kilometre L litre LED light-emitting diode m metre mm millimetre MAST Marine and Safety -

Download This PDF File

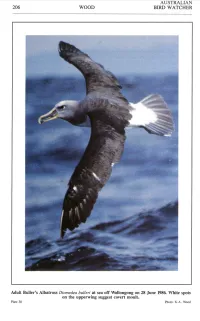

AUSTRALIAN 206 WOOD BIRD WATCHER Adult Buller's Albatross Diomedea bulleri at sea off Wollongong on 28 June 1986. White spots on the upperwing suggest covert moult. Plale 30 Phoro: K.A. Wood VOL. 14 (6) JUNE 1992 207 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1992, 14, 207-225 Seasonal Abundance and Spatial Distribution of Albatrosses off Central New South Wales by K.A. WOOD, 7 Eastern Avenue, Mangerton, N .SW. 2500 Summary Between April 1985 and March 1987, albatrosses were censused during 25 one-day transects over the continental shelf and slope off Wollongong, New South Wales. The relative abundance of common species was as follows: Black-browed Diomedea melanophrys 54%, Yellow-nosed D. chlororhynchos 34%, Wandering D. exulans 6% and Shy D. cauta 6%. Numbers of these albatrosses were seasonally highest in winter or spring and spatially highest over pelagic water. Black-browed, Yellow-nosed and Shy had highest rates of encounter over the upper slope (depth 200-1500 m) whereas Wandering was encountered most frequently over the lower slope (depth 1500-4200 m). Observation details of four irregular species are reported. The abundance of Black-browed and Yellow-nosed Albatrosses was negatively correlated with sea surface and ambient air temperatures. A preliminary assessment of the latitudinal abundance of common species off New South Wales is presented. Introduction Accounts of the abundance of albatrosses off New South Wales reflect a lack of observations over the continental slope (depth 200-4000 m) and a need for more rigorous census procedures. Marchant (1977) conducted an eleven-month study from the shore at Burrewarra Point, latitude 35 °50 'S. -

Ultimate Cruising Guests Also Receive: Chauffeur Driven Luxury Car Transfers from Your Home to the Airport and Return (Within 35Km) Cruise Highlights

ultimatecruising.com.au or call us on 1300 485 846 FROM $15,996pp Package #408 Revel in the opportunity to tread some of Tasmania’s greatest coastal tracks while you circumnavigate this island state by sea. Land on remote pristine beaches; trek through coastal heath, buttongrass moorlands, lush temperate rainforests and tall eucalypt woodlands; and drink in the stunning vistas from towering dolerite peaks. Explore islands whose only permanent inhabitants include Bennett’s wallabies, wombats, potoroos, possums and pademelons. Cruise the wild, storm-swept coastlines and sheltered, shimmering bays. Experience a variety of trekking treasures on Bruny, Flinders and Maria Islands. Delight in the raucousness of an Australian fur seal colony’s rocky haul-out on the Hunter Islands; the gregariousness of the gannets at Pedra Branca; and the majesty of a soaring shy albatross in the skies above Mewstone. Create and collate a treasured suite of memories – on foot or by sea – with extraordinary adventures on offer each day. This expedition is subject to regulatory approval and only open to Australian and New Zealand residents. Highlights include: Head off the ‘mother ship’ each day for a range of adventures and explorations that may include hiking options, wildlife watching, Zodiac cruises, diving^, snorkelling^, climbing^ or kayaking^ Access some of the best (and least) known walks in Tasmania, including those on Bruny, Flinders and Maria Islands, and the Hunter and Kent Island Groups On Maria Island – nicknamed Tasmania’s “Noah’s Ark” – enjoy an -

Papers of Theroyal Society of Tasmania 1927

lll ,- <> PAPERS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF TASMANIA 1927 THE SOUTH COAST AND PORT DAV·EY, TASMANIA, By CLIVE LoRD, F .L.S. (Director of the Tasmanian Museum). CORRIGENDA (Plates I.-XII. and Five Text figures.) (Read 11th April, 1927.) Page 187, line six-Early in 1850 sho1tld read Early INTRODUCTORY. in 1853. On 13th September, 1875, the late Hon. J. R. Scott read Page 193-The Paragraph b~ginning "The coast line'' a paper (Scott, P. & P. Roy. Soc. Tas., 1875) before this should come before "(b) Stratigraphy" ~n page 192. Society describing Port Davey. The facts contained in Scott's paper are of value at the present time to those in search of information concerning the early history of the south-western portion of Tasmania, and as in years to come information may be desired concerning the condition of the south-western regi-on half a century after Scott's account was written, the writer desires to place on record certain brief general obser vations concerning this interesting area. The remarks made in the present instance are the out come of two brief visits to this area. In January, 1926, I visited the South Coast as far as New Harbour in my own yacht Telopea. Again, in January, 1927, at the kind invi tation of Mr. M. R. Freney, I visited the S-outh C-oast and Port Davey in the ketch Len'IUL (S. Purdon, Skipper). Messrs. P. B. Nye and F. Blake of the Mines Department were also members of this latter excursion. During the recent visit to this area we landed at Cox Bight, and camped for some days before walking across and rejoining our !boat at Port Davey. -

Consultation Document on Listing Eligibility and Conservation Actions Thalassarche Cauta Cauta (Shy Albatross)

Consultation Document on Listing Eligibility and Conservation Actions Thalassarche cauta cauta (Shy Albatross) You are invited to provide your views and supporting reasons concerning: 1) the eligibility of Thalassarche cauta cauta (Shy Albatross) for inclusion on the EPBC Act threatened species list in the Endangered category 2) the necessary conservation actions for the above species. Evidence provided by experts, stakeholders and the general public are welcome. Responses can be provided by any interested person. Anyone may nominate a native species, ecological community or threatening process for listing under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) or for a transfer of an item already on the list to a new listing category. The Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) undertakes the assessment of species to determine eligibility for inclusion in the list of threatened species, and provides its recommendation to the Australian Government Minister for the Environment. Responses are to be provided in writing either by email to: [email protected] or by mail to: The Manager Territories, Environment and Treaties Section Australian Antarctic Division Department of the Environment and Energy 203 Channel Highway Kingston TAS 7050 Responses are required to be submitted by 15 February 2019. Contents of this information package Page General background information about listing threatened species 2 Information about this consultation process 3 Draft information about the species and its eligibility for listing 4 Conservation actions for the species 19 References cited 24 Consultation questions 31 Thalassarche cauta cauta (Shy Albatross) consultation Page 1 of 33 General background information about listing threatened species The Australian Government helps protect species at risk of extinction by listing them as threatened under Part 13 of the EPBC Act. -

Level: Elementary / Pre-Intermediate

Stoked! Surfboard lost in Tasmania turns up 2,700km away in Queensland Level: Elementary / Pre-intermediate 1 Warmer a. In pairs, think of all of the rivers, seas or oceans near you. b. What would happen if you dropped an object that can float into one of these rivers, oceans or seas? Where would it go? Is it possible you could find it again? Discuss your answers. 2 Key words a. Write the words in the boxes next to their meanings. Then find and underline them in the article. barnacles florescent local recognize via 1. going to one place on the way to another place 2. sea creatures that stick to objects in the sea 3. in or from the area that you are talking about 4. know what you are looking at because you have seen it before 5. a type of colour that is very bright and reflects light current logo miss remote straps 6. the parts on some surfboards that you put your feet through 7. a picture or symbol a company puts on the products they make 8. a strong movement of water in one direction 9. far away from anywhere else 10. wish you still had something that you used to have Published by Macmillan Education Ltd. © Macmillan Education Limited, 2021. Home >> Adults >> General English >> NEWS LESSONS FROM WEBSITE •PHOTOCOPIABLE•CAN BE DOWNLOADED Stoked! Surfboard lost in Tasmania turns up 2,700km away in Queensland Level: Elementary / Pre-intermediate b. Use some of the key words above to complete these sentences. 1. A strong took the boat out to sea. -

White-Capped Albatross Population Estimate — 2011/12 and 2012/13

Environmental Consultants Pty Ltd __________________________________________________________________ White-capped albatross population estimate — 2011/12 and 2012/13 Milestone 2 — Analysis of 2011/12 & 2012/13 data Report prepared for Department of Conservation Contract 4431 & Project POP2012-05 G. Barry Baker and Katrina Jensz June 2013 White-capped albatross population estimate — 2011/12 and 2012/13 Milestone 2 — Analysis of 2011/12 and 2012/13 data Executive Summary White-capped albatrosses Thalassarche steadi are endemic to New Zealand, breeding on Disappointment Island, Adams Island and Auckland Island in the Auckland Island group, and Bollons Island (50-100 pairs) in the Antipodes Island Group. Population estimates suggest most (95%) of the global population breeds on Disappointment Island, an area where access is restricted to maintain environmental values at the site. Virtually all aspects of the biology and ecology of white-capped albatrosses are poorly known and although approximate population sizes have developed there have been no well-documented population estimates for any of the colonies. Between 2006/07 and 2010/11 we undertook repeated population censuses of the white-capped albatrosses breeding in the Auckland Islands using aerial photography. These population censuses were carried out in December each year to estimate population size and track population trends. We have now undertaken two additional counts at the Auckland Islands: on 11 January 2012 and 14 January 2013 (2011/12 breeding seasons, respectively). In 2011/12 we estimated the total count of nesting white-capped albatrosses to be 93,752 (95%CI 93,140 — 94,364), 5,846 (5,604 — 5,999) and 178 (151— 205) annual breeding pairs at Disappointment Island, South West Cape and Adams Island, respectively, giving a total for these sites of 99,776 (99,144—100,408) breeding pairs. -

Overview of Tasmania's Offshore Islands and Their Role in Nature

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 154, 2020 83 OVERVIEW OF TASMANIA’S OFFSHORE ISLANDS AND THEIR ROLE IN NATURE CONSERVATION by Sally L. Bryant and Stephen Harris (with one text-figure, two tables, eight plates and two appendices) Bryant, S.L. & Harris, S. 2020 (9:xii): Overview of Tasmania’s offshore islands and their role in nature conservation.Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 154: 83–106. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.154.83 ISSN: 0080–4703. Tasmanian Land Conservancy, PO Box 2112, Lower Sandy Bay, Tasmania 7005, Australia (SLB*); Department of Archaeology and Natural History, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601 (SH). *Author for correspondence: Email: [email protected] Since the 1970s, knowledge of Tasmania’s offshore islands has expanded greatly due to an increase in systematic and regional surveys, the continuation of several long-term monitoring programs and the improved delivery of pest management and translocation programs. However, many islands remain data-poor especially for invertebrate fauna, and non-vascular flora, and information sources are dispersed across numerous platforms. While more than 90% of Tasmania’s offshore islands are statutory reserves, many are impacted by a range of disturbances, particularly invasive species with no decision-making framework in place to prioritise their management. This paper synthesises the significant contribution offshore islands make to Tasmania’s land-based natural assets and identifies gaps and deficiencies hampering their protection. A continuing focus on detailed gap-filling surveys aided by partnership restoration programs and collaborative national forums must be strengthened if we are to capitalise on the conservation benefits islands provide in the face of rapidly changing environmental conditions and pressure for future use. -

Nowhere Else on Earth

Nowhere Else on Earth: Tasmania’s Marine Natural Values Environment Tasmania is a not-for-profit conservation council dedicated to the protection, conservation and rehabilitation of Tasmania’s natural environment. Australia’s youngest conservation council, Environment Tasmania was established in 2006 and is a peak body representing over 20 Tasmanian environment groups. Prepared for Environment Tasmania by Dr Karen Parsons of Aquenal Pty Ltd. Report citation: Parsons, K. E. (2011) Nowhere Else on Earth: Tasmania’s Marine Natural Values. Report for Environment Tasmania. Aquenal, Tasmania. ISBN: 978-0-646-56647-4 Graphic Design: onetonnegraphic www.onetonnegraphic.com.au Online: Visit the Environment Tasmania website at: www.et.org.au or Ocean Planet online at www.oceanplanet.org.au Partners: With thanks to the The Wilderness Society Inc for their financial support through the WildCountry Small Grants Program, and to NRM North and NRM South. Front Cover: Gorgonian fan with diver (Photograph: © Geoff Rollins). 2 Waterfall Bay cave (Photograph: © Jon Bryan). Acknowledgements The following people are thanked for their assistance The majority of the photographs in the report were with the compilation of this report: Neville Barrett of the generously provided by Graham Edgar, while the following Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the additional contributors are also acknowledged: Neville University of Tasmania for providing information on key Barrett, Jane Elek, Sue Wragge, Chris Black, Jon Bryan, features of Tasmania’s marine -

Yellow Throat Turns 100! Editor YELLOW THROAT This Issue Is the 100Th Since Yellow Throat First Appeared in March 2002

Yellow Throat turns 100! Editor YELLOW THROAT This issue is the 100th since Yellow Throat first appeared in March 2002. To mark the occasion, and to complement the ecological focus of the following article by Mike The newsletter of BirdLife Tasmania Newman, here is a historical perspective, which admittedly goes back a lot further than a branch of BirdLife Australia the newsletter, and the Number 100, July 2018 organisation! Originally described by French ornithologist General Meeting for July Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1817, and Life Sciences Building, UTas, named Ptilotus Flavillus, specimens of Thursday, 12 July, 7.30 p.m. the Yellow-throated Matthew Fielding: Raven populations are enhanced by wildlife roadkill but do not Honeyeater were impact songbird assemblages. ‘collected’ by John Future land-use and climate change could supplement populations of opportunistic Gould during his visit predatory birds, such as corvids, resulting in amplified predation pressure and negative to Tasmania with his effects on populations of other avian species. Matt, a current UTas PhD candidate, will wife Elizabeth in 1838. provide an overview of his Honours study on the response of forest raven (Corvus This beautiful image tasmanicus) populations to modified landscapes and areas of high roadkill density in south- was part of the eastern Tasmania. exhibition ‘Bird Caitlan Geale: Feral cat activity at seabird colonies on Bruny Island. Woman: Elizabeth Using image analysis and modelling, Caitlin’s recent Honours project found that feral cats Gould and the birds of used the seabird colonies studied as a major food resource during the entire study period, and Australia’ at the native predators did not appear to have a large impact. -

Dispersal of Activities-The East Tasmanian Aboriginal Sites

IYAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE ROYAL SOGIETY OF TASMA~IA. VOLUME 102-PART II DISPERSAL OF ACTIVITIES-THE EAST TASMANIAN ABORIGINAL SITES By HARRY LOURANDOS Tasmanian Museum, Hobart ABSTl~ACT of the .economically obtainable(l) shell population The archaeological evidence both from excavated m the lmmediately related habitat, with few other sites and field survey suggests a significant division extraneous features associated. From Great Oyster in the prehistoric economic organisation of the Tas Bay south the coastline is broken and indented in manian Aborigines of the East and West/North series of protected bays, and here and in the West habitats of the island. A nomadic organisa e_~~uaries the bay-estuarine type predominates, tion is interpreted for the Eastern sites, and a Ii 10m field surveys It appears to directly correspond semi-sedentary or seasonally-sedentary organisation to the distribution of the living and historically recorded shell populations. The two shell specie's for the West and North-West coastal sites. that compose the bulk of these middens are the Tas,manian mud oyster .(Ostrea angas·i Sowerby. INTRODUCTION 187~) and mussel (Mytllus pianulatus Lamarck. Here is a scheme based on field survey and exca 1819) ,and th,:y occur together in differing ratios vation for organising and interpreting the or maependentJy accordmg to the structure of the archaeological sites of Eastern Tasmania. Three aSSOCiated shell populations. North of Great types of site are distingUished and shown to be Oystel~ Bay .as far as Eddystone Point the domin related spatially and in function. These are shell ant mIdden IS .of the second type directly associated middens, open inland camps, and the quarries.