White-Capped Albatross Population Estimate — 2011/12 and 2012/13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Recovery Plan for Threatened Albatrosses and Giant Petrels 2011-2016

National recovery plan for threatened albatrosses and giant petrels 2011-2016 National recovery plan for threatened albatrosses and giant petrels 2011-2016 © Commonwealth Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgment of the sources but no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Strategies Branch Australian Antarctic Division Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities 203 Channel Highway KINGSTON TAS 7050 Citation Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2011), National recovery plan for threatened albatrosses and giant petrels 2011-2016, Commonwealth of Australia, Hobart Acknowledgements This Plan was developed by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) of the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. The AAD is grateful for the support of a wide range of organisations and individuals, who provided valuable information and assistance during the preparation of this Plan. Particular thanks to: - Ms Rachael Alderman and Dr Rosemary Gales from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment, Tasmania; and - Mr Ian Hay, Ms Tara Hewitt, Dr Graham Robertson and Dr Mike Double of the AAD. Cover photograph: Light mantled albatross and chick, North Head, Macquarie Island, 2010; photographer Sarah Way, Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment. i Introduction The first Recovery Plan for albatrosses and giant petrels was released in October 2001 in recognition of the need to develop a co-ordinated conservation strategy for albatrosses and giant petrels listed threatened under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). -

Download This PDF File

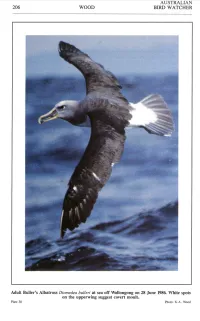

AUSTRALIAN 206 WOOD BIRD WATCHER Adult Buller's Albatross Diomedea bulleri at sea off Wollongong on 28 June 1986. White spots on the upperwing suggest covert moult. Plale 30 Phoro: K.A. Wood VOL. 14 (6) JUNE 1992 207 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1992, 14, 207-225 Seasonal Abundance and Spatial Distribution of Albatrosses off Central New South Wales by K.A. WOOD, 7 Eastern Avenue, Mangerton, N .SW. 2500 Summary Between April 1985 and March 1987, albatrosses were censused during 25 one-day transects over the continental shelf and slope off Wollongong, New South Wales. The relative abundance of common species was as follows: Black-browed Diomedea melanophrys 54%, Yellow-nosed D. chlororhynchos 34%, Wandering D. exulans 6% and Shy D. cauta 6%. Numbers of these albatrosses were seasonally highest in winter or spring and spatially highest over pelagic water. Black-browed, Yellow-nosed and Shy had highest rates of encounter over the upper slope (depth 200-1500 m) whereas Wandering was encountered most frequently over the lower slope (depth 1500-4200 m). Observation details of four irregular species are reported. The abundance of Black-browed and Yellow-nosed Albatrosses was negatively correlated with sea surface and ambient air temperatures. A preliminary assessment of the latitudinal abundance of common species off New South Wales is presented. Introduction Accounts of the abundance of albatrosses off New South Wales reflect a lack of observations over the continental slope (depth 200-4000 m) and a need for more rigorous census procedures. Marchant (1977) conducted an eleven-month study from the shore at Burrewarra Point, latitude 35 °50 'S. -

Consultation Document on Listing Eligibility and Conservation Actions Thalassarche Cauta Cauta (Shy Albatross)

Consultation Document on Listing Eligibility and Conservation Actions Thalassarche cauta cauta (Shy Albatross) You are invited to provide your views and supporting reasons concerning: 1) the eligibility of Thalassarche cauta cauta (Shy Albatross) for inclusion on the EPBC Act threatened species list in the Endangered category 2) the necessary conservation actions for the above species. Evidence provided by experts, stakeholders and the general public are welcome. Responses can be provided by any interested person. Anyone may nominate a native species, ecological community or threatening process for listing under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) or for a transfer of an item already on the list to a new listing category. The Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) undertakes the assessment of species to determine eligibility for inclusion in the list of threatened species, and provides its recommendation to the Australian Government Minister for the Environment. Responses are to be provided in writing either by email to: [email protected] or by mail to: The Manager Territories, Environment and Treaties Section Australian Antarctic Division Department of the Environment and Energy 203 Channel Highway Kingston TAS 7050 Responses are required to be submitted by 15 February 2019. Contents of this information package Page General background information about listing threatened species 2 Information about this consultation process 3 Draft information about the species and its eligibility for listing 4 Conservation actions for the species 19 References cited 24 Consultation questions 31 Thalassarche cauta cauta (Shy Albatross) consultation Page 1 of 33 General background information about listing threatened species The Australian Government helps protect species at risk of extinction by listing them as threatened under Part 13 of the EPBC Act. -

Tracking Ocean Wanderers: the Global Distribution of Albatrosses and Petrels

TRACKINGTRACKING OCEANOCEAN WANDERERSWANDERERS TheThe globalglobal distributiondistribution ofof albatrossesalbatrosses andand petrelspetrels Results from the Global Procellariiform Tracking Workshop, 1–5 September, 2003, Gordon’s Bay, South Africa What is BirdLife International? BirdLife International is a Partnership of non-governmental conservation organisations with a special focus on birds. The BirdLife Partnership works together on shared priorities, policies and programmes of conservation action, exchanging skills, achievements and information, and so growing in ability, authority and influence. What is the purpose of BirdLife International? – Mission Statement The BirdLife International Partnership strives to conserve birds, their habitats and global biodiversity, working with people towards sustainability in the use of natural resources. Where is BirdLife International heading? – Vision Statement Birds are beautiful, inspirational and international. Birds are excellent flagships and vital environmental indicators. By focusing on birds, and the sites and habitats on which they depend, the BirdLife International Partnership is working to improve the quality of life for birds, for other wildlife (biodiversity) and for people. Aims Birdlife’s long-term aims are to: • Prevent the extinction of any bird species • Maintain and where possible improve the conservation status of all bird species • Conserve and where appropriate improve and enlarge sites and habitats important for birds • Help, through birds, to conserve biodiversity and to improve the quality of people’s lives • Integrate bird conservation into sustaining people’s livelihoods. Guiding principles BirdLife International works with all like-minded organisations, national and local governments, decision-makers, land-owners and managers, in pursuing bird and biodiversity conservation. The global work of the BirdLife Partnership is funded entirely by voluntary donations. -

Analysis of Albatross and Petrel Distribution Within the CCAMLR Convention Area: Results from the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database

CCAMLR Science, Vol. 13 (2006): 143–174 ANALYSIS OF ALBATROSS AND PETREL DISTRIBUTION WITHIN THE CCAMLR CONVENTION AREA: RESULTS FROM THE GLOBAL PROCELLARIIFORM TRACKING DATABASE BirdLife International (prepared by C. Small and F. Taylor) Wellbrook Court, Girton Road Cambridge CB3 0NA United Kingdom Correspondence address: BirdLife Global Seabird Programme c/o Royal Society for the Protection of Birds The Lodge, Sandy Bedfordshire SG19 2DL United Kingdom Email – [email protected] Abstract CCAMLR has implemented successful measures to reduce the incidental mortality of seabirds in most of the fisheries within its jurisdiction, and has done so through area- specific risk assessments linked to mandatory use of measures to reduce or eliminate incidental mortality, as well as through measures aimed at reducing illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. This paper presents an analysis of the distribution of albatrosses and petrels in the CCAMLR Convention Area to inform the CCAMLR risk- assessment process. Albatross and petrel distribution is analysed in terms of its division into FAO areas, subareas, divisions and subdivisions, based on remote-tracking data contributed to the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database by multiple data holders. The results highlight the importance of the Convention Area, particularly for breeding populations of wandering, grey-headed, light-mantled, black-browed and sooty albatross, and populations of northern and southern giant petrel, white-chinned petrel and short- tailed shearwater. Overall, the subareas with the highest proportion of albatross and petrel breeding distribution were Subareas 48.3 and 58.6, adjacent to the southwest Atlantic Ocean and southwest Indian Ocean, but albatross and petrel breeding ranges extend across the majority of the Convention Area. -

Noteworthy Seabird Records from Paraná State, Southern Brazil by Nicholas Winterle Daudt, Alice Pereira, Juliana Rechetelo, Ricardo Krul & Luiz Augusto Macedo Mestre

Nicholas Winterle Daudt et al. 195 Bull. B.O.C. 2017 137(3) Noteworthy seabird records from Paraná state, southern Brazil by Nicholas Winterle Daudt, Alice Pereira, Juliana Rechetelo, Ricardo Krul & Luiz Augusto Macedo Mestre Received 16 March 2017; revised 28 July 2017; published 15 September 2017 htp://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:3E863833-C195-4A8F-A59A-8F2551C71EE0 Summary.—We inventoried seabird specimens—skeletons and skins—collected during beach surveys of Paraná, south Brazil, both the mainland coast and ofshore islets during the period 1992–94. We found 184 specimens comprising four orders and 17 species. This represents the most important collection of seabirds from Paraná and includes three new records for the state, Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis, Sooty Shearwater Pufnus griseus and Snowy Sheathbill Chionis albus. We recommend the removal of two species from the avifauna of Paraná—Shy Albatross Thalassarche cauta and Broad-billed Prion Pachyptila vitata—due to the lack of tangible evidence. All of this material is held in publicly accessible natural history museums. Natural history museums and their research collections play an important role in cataloguing biodiversity. Material held in museums aids our understanding of species diversity, evolution and genetics (Winker 2005). Collections are also important for educational and cultural reasons (Arinze 1999). They represent biological ‘libraries’ and their databases provide a robust starting point for scientifc studies (Suarez & Tsutsui 2004, Joseph 2011). In Brazil, three museums specialise in seabirds: the Museu de Ciências Naturais da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Imbé (MUCIN) and Coleção de Aves da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul—FURG, Rio Grande (CAFURG), both in Rio Grande do Sul state, and the Museu Oceanográfco do Vale do Itajaí, Itajaí (MOVI) in Santa Catarina state. -

New Records of Shy-Type Albatrosses Thalassarche Cauta/T. Steadi Off the Argentine Continental Shelf

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 21(4), 263-268 ARTICLE December 2013 New records of shy-type albatrosses Thalassarche cauta/T. steadi off the Argentine Continental Shelf Juan Pablo Seco Pon1,3 and Leandro Tamini2 1 Grupo Vertebrados. Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras (IIMyC), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) –Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata (UNMdP). Funes 3250 (B7602AYJ), Mar del Plata, Argentina. 2 Albatross Task Force Argentina – Aves Argentinas/Birdlife International. Matheu 1246/8 (C1249AAB), Buenos Aires, Argentina. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 16 January 2013. Accepted on 20 November 2013. ABSTRACT: Shy Thalassarche cauta and White-capped albatrosses T. steadi are two taxa for which specific status has recently been posited, however, owing to their morphological resemblance they are frequently referred to as “shy-type” albatrosses. Information on the distribution of this albatross complex in the Argentine Continental Shelf is particularly scarce and limited to only a few observations, chiefly obtained in the Argentine-Uruguayan Common Fishing Zone and in the vicinity of the Malvinas (Falkland) Islands; there is virtually no information for other oceanic areas (continental shelf, shelf-break area and slope). New records of shy- type albatrosses were obtained during the development of project assessments of the interaction between commercial trawl fisheries and seabirds attending waters of the Argentine Continental Shelf. The observation effort (counts during trawling operations) covered all seasons in a four-year span. These records provide new information on the presence and abundance of this albatross complex for a wide latitudinal range off Argentina that is also an area of operation of trawling fishing fleets (e.g. -

WHITE-CAPPED ALBATROSS (SHY ALBATROSS | Thalassarche Steadi

WHITE-CAPPED ALBATROSS (SHY ALBATROSS | Thalassarche steadi D Boyer; RE Simmons | Reviewed by: R Wanless © John Paterson Conservation Status: Near Threatened Southern African Range: Waters off Namibia, South Africa, southern Mozambique Area of Occupancy: Unknown Population Estimate: Unknown Population Trend: Possibly declining Habitat: Continental shelf and shelf break waters Threats: Bycatch in longline and trawl fisheries 190 BIRDS TO WATCH IN NAMIBIA in winters (Crawford et al. 1991). Although thought to be more common in winter (Liversidge & Le Gras 1981, Ryan & Rose 1989), in the period between 1989 and 2003, the species was sighted most frequently between July and March, with a decline in abundance between April and June (Boyer & Boyer 2005). Up to 90% of birds were estimated to occur off northern Namibia during the 1970s and 1980s (Crawford et al. 1991), but more recent surveys indicated that most sightings occurred on the continental shelf off central and southern Namibia (Boyer & Boyer 2005). The White-capped Albatross is recorded three to four times less frequently than the Black-browed and Yellow- nosed albatrosses in Namibia (Boyer & Boyer 2005). Between 1995 and 2003, the frequency of sightings in Namibia had declined three-fold compared to that recorded between 1989 and 1994 (Boyer & Boyer 2005). However, this apparent decline may have been the result of a change in local distribution following the 1995 Benguela Niño, rather than an indication of a global decline. DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE The White-capped Albatross was historically considered ECOLOGY a subspecies of the Shy Albatross Diomedea cauta, which has since been moved to Thalassarche and in The breeding biology and breeding phenology of 2006 was split into four species that include the White- the White-capped Albatross are poorly known. -

Shy Albatross

THREATENED SPECIES INFORMATION Shy Albatross Diomedea cauta Gould, 1841 Other common names White-capped Albatross, Mollymawk Conservation status The Shy Albatross has a predominantly white body with dark grey wings and back. The Shy Albatross is listed as a Vulnerable The brow is dark-grey or black and a light Species on Schedule 2 of the New South grey wash covers the sides of head, neck Wales Threatened Species Conservation and throat. The underwing is white with Act, 1995 (TSC Act). black edges and tip and a characteristic Description (summarised from Schodde & black patch where the wing joins the body. Tidemann 1988; Marchant & Higgins 1990) The bill is grey with a yellow tip and black nasal groove. The feet, toes and web are Head and Body Length blue-grey. 90-100cm Wingspan Juveniles are similar to adults but with 212-256cm darker grey wash on the side of head or a Wing completely grey head. The juvenile’s bill 56-61cm and feet are also darker. Tail 22-23cm Distribution Bill 12-14cm The Shy Albatross is circumpolar in Tarsus distribution, occurring widely in the 8-10cm southern oceans around the southern Weight margins of South America, New Zealand, 4-4.4 kg (male) Australia and South Africa. Islands off 3.4-3.8kg (female) Australia and New Zealand provide Graham Robertson/NPWS Shy Albatross x #Y Lismore #Y Tibooburra #Y Moree #Y Grafton #Y Bourke #Y Tamworth #Y Port Macquarie $ #Y Broken Hill #Y $$ Dubbo #Y N$ewcastle $$$$ $ r#Y N $r$Sydney #Y Griffith W E #Y $$$$$ $$$ Wollongong S #Y $ Wagga Wagga $ $ $ $ $ Th e sightin gs represented on th is map are #Y only indicative. -

SEABIRD BYCATCH IDENTIFICATION GUIDE UPDATED AUGUST 2015 2 How to Use This Guide

SEABIRD BYCATCH IDENTIFICATION GUIDE UPDATED AUGUST 2015 2 How to use this guide 1. Identify the bird • Start by looking at its bill - size and position of nostrils as shown on pages 6-9 to decide if it’s an albatross, a petrel or another group. • If it’s an albatross, use the keys and photos on pages 10-13, to identify the bird to a particular species (or to the 2 or 3 species that it might be), and go to the page specified to confirm the identification. If it’s a petrel, use the key on pages 14-15 , then go to the page as directed. If it’s a shearwater, look at pages 66-77. 2. Record Record your identification in the logbook choosing one of the FAO codes, or a combination of codes from the list on pages 96-99. 3. Take photos Take three photos of the bird as shown on pages 78-81 and submit with the logbook. 4. Sample feathers If a sampling programme is in place, pluck some feathers for DNA analysis as shown on pages 82-83. SEABIRD BYCATCH IDENTIFICATION GUIDE 3 Contents How to use this guide 2 Measuring bill and wing length 4 Albatross, Petrel or other seabird? 6 Bill guide 8 Albatross key 10 Diomedea albatross key 12 Juvenile/Immature Thalassarche key 13 Petrel key 14 North Pacific Albatrosses 16 - 21 Waved Albatross 22 Phoebetria albatrosses (light-mantled and sooty) 24 - 27 Royal albatrosses 28 - 29 ‘Wandering-type’ albatrosses 30 - 37 Thalassarche albatrosses 38 - 51 Juvenile/Immature Thalassarche albatrosses 52 - 53 Giant petrels 54 - 55 Procellaria petrels 56 - 61 Other Petrels 62 - 65 Shearwaters 66 - 77 Data collection protocols - taking photos 78 Data collection protocols - examples of photos 80 Data collection protocols - feather samples for DNA analysis 82 Leg Bands 84 References 88 Your feedback 91 Hook Removal from Seabirds 92 Albatross species list 96 Petrel and Shearwater species list 98 4 Measuring Bill & Wing Length BILL LENGTH WING LENGTH 10 20 Ruler 30 (mm) 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140 150 160 170 180 190 200 6 Albatross, Petrel, Shearwater Albatrosses Page 10 Separate nostrils. -

Chatham Albatross Thalassarche Eremita

Chatham Albatross Thalassarche eremita Albatros des Chatham Albatros de Chatham CRITICALLY ENDANGERED ENDANGERED VULNERABLE NEAR THREATENED LEAST CONCERN NOT LISTED Sometimes referred to as Chatham Island Albatross Chatham Island Mollymawk Chatham Mollymawk TAXONOMY Photo © Tui De Roy, not to be used without photographer‟s permission Order Procellariiformes CONSERVATION LISTINGS AND PLANS Family Diomedeidae Genus Thalassarche International Species T. eremita . Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels – Annex 1 [4] Thalassarche eremita was previously . 2010 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species – Vulnerable [9] considered to be a member of the . Convention on Migratory Species - Appendix II (as Diomedea cauta) [10] polytypic species Diomedea cauta (Gould 1841). Following the transfer Australia of D. cauta to the genus . Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Thalassarche [1], T. eremita was ACT) [11] elevated to specific status along with − Endangered − Migratory other taxa in the Shy group, T. salvini − Marine (Salvin‟s Albatross) and T. cauta . Recovery Plan for Albatrosses and Petrels (2001) [12] (Shy Albatross), which was further . Threat Abatement Plan 2006 for the incidental catch (or bycatch) of split into T. cauta and T. steadi seabirds during oceanic longline fishing operations [13] (White-capped Albatross) by [2] Robertson and Nunn (1998) . The Chile recognition of T. eremita remains . National Plan of Action for reducing by-catch of seabirds in longline controversial [3] but this classification fisheries (PAN-AM/CHILE) 2007 [14] has been adopted by ACAP [4], BirdLife International [5], and several New Zealand [15] recent handbooks and field guides of . Wildlife Act 1953 Southern Ocean seabirds [6, 7, 8]. -

Salvin's Albatross

Salvin’s Albatross Thalassarche salvini Albatros de Salvin Albatros de Salvin / Albatros de frente blanca CRITICALLY ENDANGERED ENDANGERED VULNERABLE NEAR THREATENED LEAST CONCERN NOT LISTED Sometimes referred to as Grey-backed Albatross Salvin’s Mollymawk TAXONOMY Photo © Tui De Roy, not to be used without photographer’s permission Order Procellariiformes Family Diomedeidae CONSERVATION LISTINGS AND PLANS Genus Thalassarche International Species T. salvini Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels – Annex 1 [3] Thalassarche salvini was previously 2009 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species – Vulnerable (since 2000) [7] considered to be a member of the [8] polytypic species Diomedea cauta Convention on Migratory Species - Appendix II (as Diomedea cauta ) (Gould 1841). Following the transfer Australia of D. cauta to the genus Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Thalassarche [1] , T. salvini was ACT ) [9] elevated to specific status along with − Listed Threatened Species – Endangered (as Thalassarche other taxa in the Shy group, T. cauta salvini ) eremita (Chatham Albatross) and T. − Listed Migratory Species cauta (Shy Albatross), which was − Listed Marine Species further split into T. cauta and T. Recovery Plan for Albatrosses and Petrels (2001) [10] steadi (White-capped Albatross) by Threat Abatement Plan 2006 for the incidental catch (or bycatch) of Robertson and Nunn (1998) [2] . This seabirds during oceanic longline fishing operations [11] classification has been adopted by South Australia: National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 – Vulnerable (as ACAP [3] , BirdLife International [4] , Diomedea cauta salvini ) [12] and several recent handbooks and Western Australia: Wildlife conservation Act 1950 - Wildlife field guides of Southern Ocean Conservation (Specially Protected Fauna) Notice 2008 (2) – Fauna that seabirds [5, 6] .