Chatham Albatross Thalassarche Eremita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plumage Variation and Hybridization in Black-Footed and Laysan Albatrosses

PlumaDevariation and hybridizationin Black-footedand LaysanAlbatrosses Tristan McKee P.O. Box631 Ferndale,California 95536 (eraall:bertmckee•yahoo.com) PeterPyle 4990Shoreline Highway SUnsonBeach, California 94970 (email:[email protected]) INTRODUCTION Black-footed(Phoebastria nigripes) and Laysan (P. immutabilis) Albatrosses nest sideby sidein denseisland colonies. Their breeding populations center in the northwesternHawaiian Islands, with smaller colonies scattered across the subtrop- icalNorth Pacific. Both species visit nutrient-rich waters off the west coast of North Americathroughout the year to forage. Black-footeds concentrate in coastal waters fromnorthern California tosouthern Alaska, while Laysans frequent more offshore andnortherly waters in thisregion. Bkders on pelagic trips off the West Coast often encountersignificant numbers of oneor bothof thesespecies, and searching for other,rarer albatrosses among them has proven to be a worthwhile pursuit in recen! years(Stallcup and Terrill 1996, Cole 2000). Albatrossesidentified as Black-looted x Laysan hybrids have been seen and studiedon MidwayAtoll and other northwestern Hawaiian Islands since the late 1800s(Rothschild 1900, Fisher 1948, 1972). In addition,considerable variation in appearanceis found within both species, indMduals with strikinglyaberrant plumageand soft part colors occasionally being encountered (Fisher 1972, Whittow 1993a).Midway Atoll hosts approximately two-thirds of the world'sbreeding A presumedhybrid Laysan x Black-lootedAlbatross tends a chickat Midway LaysanAlbatrosses -

Tube-Nosed Seabirds) Unique Characteristics

PELAGIC SEABIRDS OF THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM & CORDELL BANK NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Written by Carol A. Keiper August, 2008 Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary protects an area of 529 square miles in one of the most productive offshore regions in North America. The sanctuary is located approximately 43 nautical miles northwest of the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Francisco California. The prominent feature of the Sanctuary is a submerged granite bank 4.5 miles wide and 9.5 miles long, which lay submerged 115 feet below the ocean’s surface. This unique undersea topography, in combination with the nutrient-rich ocean conditions created by the physical process of upwelling, produces a lush feeding ground. for countless invertebrates, fishes (over 180 species), marine mammals (over 25 species), and seabirds (over 60 species). The undersea oasis of the Cordell Bank and surrounding waters teems with life and provides food for hundreds of thousands of seabirds that travel from the Farallon Islands and the Point Reyes peninsula or have migrated thousands of miles from Alaska, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Cordell Bank is also known as the albatross capital of the Northern Hemisphere because numerous species visit these waters. The US National Marine Sanctuaries are administered and managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who work with the public and other partners to balance human use and enjoyment with long-term conservation. There are four major orders of seabirds: 1) Sphenisciformes – penguins 2) *Procellariformes – albatross, fulmars, shearwaters, petrels 3) Pelecaniformes – pelicans, boobies, cormorants, frigate birds 4) *Charadriiformes - Gulls, Terns, & Alcids *Orders presented in this seminar In general, seabirds have life histories characterized by low productivity, delayed maturity, and relatively high adult survival. -

NSW Vagrant Bird Review

an atlas of the birds of new south wales and the australian capital territory Vagrant Species Ian A.W. McAllan & David J. James The species listed here are those that have been found on very few occasions (usually less than 20 times) in NSW and the ACT, and are not known to have bred here. Species that have been recorded breeding in NSW are included in the Species Accounts sections of the three volumes, even if they have been recorded in the Atlas area less than 20 times. In determining the number of records of a species, when several birds are recorded in a short period together, or whether alive or dead, these are here referred to as a ‘set’ of records. The cut-off date for vagrant records and reports is 31 December 2019. As with the rest of the Atlas, the area covered in this account includes marine waters east from the NSW coast to 160°E. This is approximately 865 km east of the coast at its widest extent in the south of the State. The New South Wales-Queensland border lies at about 28°08’S at the coast, following the centre of Border Street through Coolangatta and Tweed Heads to Point Danger (Anon. 2001a). This means that the Britannia Seamounts, where many rare seabirds have been recorded on extended pelagic trips from Southport, Queensland, are east of the NSW coast and therefore in NSW and the Atlas area. Conversely, the lookout at Point Danger is to the north of the actual Point and in Queensland but looks over both NSW and Queensland marine waters. -

National Recovery Plan for Threatened Albatrosses and Giant Petrels 2011-2016

National recovery plan for threatened albatrosses and giant petrels 2011-2016 National recovery plan for threatened albatrosses and giant petrels 2011-2016 © Commonwealth Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgment of the sources but no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Strategies Branch Australian Antarctic Division Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities 203 Channel Highway KINGSTON TAS 7050 Citation Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2011), National recovery plan for threatened albatrosses and giant petrels 2011-2016, Commonwealth of Australia, Hobart Acknowledgements This Plan was developed by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) of the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. The AAD is grateful for the support of a wide range of organisations and individuals, who provided valuable information and assistance during the preparation of this Plan. Particular thanks to: - Ms Rachael Alderman and Dr Rosemary Gales from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment, Tasmania; and - Mr Ian Hay, Ms Tara Hewitt, Dr Graham Robertson and Dr Mike Double of the AAD. Cover photograph: Light mantled albatross and chick, North Head, Macquarie Island, 2010; photographer Sarah Way, Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment. i Introduction The first Recovery Plan for albatrosses and giant petrels was released in October 2001 in recognition of the need to develop a co-ordinated conservation strategy for albatrosses and giant petrels listed threatened under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). -

LAYSAN ALBATROSS Phoebastria Immutabilis

Alaska Seabird Information Series LAYSAN ALBATROSS Phoebastria immutabilis Conservation Status ALASKA: High N. AMERICAN: High Concern GLOBAL: Vulnerable Breed Eggs Incubation Fledge Nest Feeding Behavior Diet Nov-July 1 ~ 65 d 165 d ground scrape surface dip fish, squid, fish eggs and waste Life History and Distribution Laysan Albatrosses (Phoebastria immutabilis) breed primarily in the Hawaiian Islands, but they inhabit Alaskan waters during the summer months to feed. They are the 6 most abundant of the three albatross species that visit 200 en Alaska. l The albatross has been described as the “true nomad ff Pok e of the oceans.” Once fledged, it remains at sea for three to J ht ig five years before returning to the island where it was born. r When birds are eight or nine years old they begin to breed. y The breeding season is November to July and the rest of Cop the year, the birds remain at sea. Strong, effortless flight is commonly seen in the southern Bering Sea, Aleutian the key to being able to spend so much time in the air. The Islands, and the northwestern Gulf of Alaska. albatross takes advantage of air currents just above the Nonbreeders may remain in Alaska throughout the year ocean's waves to soar in perpetual fluid motion. It may not and breeding birds are known to travel from Hawaii to flap its wings for hours, or even for days. The aerial Alaska in search of food for their young. Albatrosses master never touches land outside the breeding season, but have the ability to concentrate the food they catch and it does rest on the water to feed and sleep. -

SEABIRDS RECORDED at the CHATHAM ISLANDS, 1960 to MAY 1993 by M.J

SEABIRDS RECORDED AT THE CHATHAM ISLANDS, 1960 TO MAY 1993 By M.J. IMBER Science and Research Directorate, Department of Conservation, P. 0. Box 10420, Wellington ABSTRACT Between 1960 and hlay 1993,62 species of seabirds were recorded at Chatham Islands, including 43 procellariiforms, 5 penguins, 5 pelecaniforms, and 9 hi.Apart &om the 24 breeding species, there were 14 regular visitors, 13 stragglers, 2 rarely seen on migration, and 9 found only beach-cast or as other remains. There is considerable endemism: 8 species or subspecies are confined, or largely confined, to breeding at the Chathams. INTRODUCTION The Chatham Islands (44OS, 176.5OW) are about 900 km east of New Zealand, and 560 km and 720 km respectively north-east of Bounty and Antipodes Islands. The Chatham Islands lie on the Subtropical Convergence (Fleming 1939) - the boundary between subtropical and subantarctic water masses; near the eastern end of the Chatham Rise - a shallow (4'500 m) submarine ridge extending almost to the New Zealand mainland. Chatham Island seabirds can feed over large areas of four marine habitats: the continental shelf of the Chatham Rise; the continental slope around it; and subtropical and subantarctic waters to the north, east, and south. The Chatham Islands' fauna and flora have, however, been very adversely affected by human colonisation for about 500 years (B. McFadgen, pers. cornrn.). Knowledge of the seabird fauna of the Chatham Islands gained up to 1960 is siunmarised in Oliver (1930), Fleming (1939), Dawson (1955, 1973), and papers quoted therein. The present paper summarises published and unpublished data on the seabirds of the archipelago from 1960 to May 1993, from when visits to these islands depended on infrequent passages by ship from Lyttelton, South Island, to the present, when a visit involves a 2-h scheduled flight from Napier, Wellington, or Christchurch, six dayslweek. -

Parasites of the Neotropic Cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) Brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) in Chile

Original Article ISSN 1984-2961 (Electronic) www.cbpv.org.br/rbpv Parasites of the Neotropic cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) in Chile Parasitos da biguá Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) do Chile Daniel González-Acuña1* ; Sebastián Llanos-Soto1,2; Pablo Oyarzún-Ruiz1 ; John Mike Kinsella3; Carlos Barrientos4; Richard Thomas1; Armando Cicchino5; Lucila Moreno6 1 Laboratorio de Parásitos y Enfermedades de Fauna Silvestre, Departamento de Ciencia Animal, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad de Concepción, Chillán, Chile 2 Laboratorio de Vida Silvestre, Departamento de Ciencia Animal, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad de Concepción, Chillán, Chile 3 Helm West Lab, Missoula, MT, USA 4 Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Santo Tomás, Concepción, Chile 5 Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata, Argentina 6 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas, Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile How to cite: González-Acuña D, Llanos-Soto S, Oyarzún-Ruiz P, Kinsella JM, Barrientos C, Thomas R, et al. Parasites of the Neotropic cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) in Chile. Braz J Vet Parasitol 2020; 29(3): e003920. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612020049 Abstract The Neotropic cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Suliformes: Phalacrocoracidae) is widely distributed in Central and South America. In Chile, information about parasites for this species is limited to helminths and nematodes, and little is known about other parasite groups. This study documents the parasitic fauna present in 80 Neotropic cormorants’ carcasses collected from 2001 to 2008 in Antofagasta, Biobío, and Ñuble regions. Birds were externally inspected for ectoparasites and necropsies were performed to examine digestive and respiratory organs in search of endoparasites. -

Albatross Or Mōlī (Phoebastria Immutabilis) Black-Footed Albatross Or Ka’Upu (Phoebastria Nigripes) Short-Tailed Albatross (Phoebastria Albatrus)

Hawaiian Bird Conservation Action Plan Focal Species: Laysan Albatross or Mōlī (Phoebastria immutabilis) Black-footed Albatross or Ka’upu (Phoebastria nigripes) Short-tailed Albatross (Phoebastria albatrus) Synopsis: These three North Pacific albatrosses are demographically similar, share vast oceanic ranges, and face similar threats. Laysan and Black-footed Albatrosses nest primarily in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, while the Short-tailed Albatross nests mainly on islands near Japan but forages extensively in U.S. waters. The Short-tailed Albatross was once thought to be extinct but its population has been growing steadily since it was rediscovered in 1951 and now numbers over 3,000 birds. The Laysan is the most numerous albatross species in the world with a population over 1.5 million, but its trend has been hard to determine because of fluctuations in number of breeding pairs. The Black-footed Albatross is one-tenth as numerous as the Laysan and its trend also has been difficult to determine. Fisheries bycatch caused unsustainable mortality of adults in all three species but has been greatly reduced in the past 10-20 years. Climate change and sea level rise are perhaps the greatest long-term threat to Laysan and Black-footed Albatrosses because their largest colonies are on low-lying atolls. Protecting and creating colonies on higher islands and managing non-native predators and human conflicts may become keys to their survival. Laysan, Black-footed, and Short-tailed Albatrosses (left to right), Midway. Photos Eric VanderWerf Status -

Evaluating Threats to New Zealand Seabirds Report for the Department of Conservation

Evaluating threats to New Zealand seabirds Report for the Department of Conservation Authors: Edward Abraham Yvan Richard Katherine Clements PO Box 27535, Wellington 6141 New Zealand dragonfly.co.nz Cover Notes To be cited as: Abraham, Edward; Yvan Richard; Katherine Clements (2016). Evaluating threats to New Zealand seabirds, 19 pages. Report for the Department of Conservation. Crown copyright © This report is licensed for re-use under a Creative Commons Aribution 3.0 New Zealand Licence. This allows you to distribute, use, and build upon this work, provided credit is given to the original source. Cover image: hps://www.flickr.com/photos/4nitsirk/16121373851 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The New Zealand Department of Conservation is developing a seabird threat framework, “to beer understand, and manage, at-sea threats to our seabirds”. This framework will allow the impact of threats on seabird populations to be qualitatively assessed, and will be used to prioritise a programme of seabird population monitoring. As a first stage in developing the framework, a database of demographic parameters and threats was prepared. In this project, a process was estab- lished for reviewing and synthesising this information. The demographic parameters were then used to develop an online tool, which allowed for the impact of changes in parameters on population growth rates to be assessed. In the future, this tool will allow the impact of current and potential threats on seabird populations to be promptly explored. The process was trialled on the 12 albatross taxa recognised -

Download This PDF File

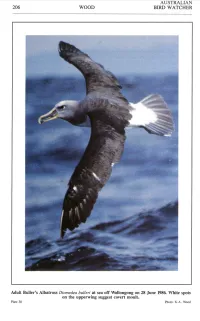

AUSTRALIAN 206 WOOD BIRD WATCHER Adult Buller's Albatross Diomedea bulleri at sea off Wollongong on 28 June 1986. White spots on the upperwing suggest covert moult. Plale 30 Phoro: K.A. Wood VOL. 14 (6) JUNE 1992 207 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1992, 14, 207-225 Seasonal Abundance and Spatial Distribution of Albatrosses off Central New South Wales by K.A. WOOD, 7 Eastern Avenue, Mangerton, N .SW. 2500 Summary Between April 1985 and March 1987, albatrosses were censused during 25 one-day transects over the continental shelf and slope off Wollongong, New South Wales. The relative abundance of common species was as follows: Black-browed Diomedea melanophrys 54%, Yellow-nosed D. chlororhynchos 34%, Wandering D. exulans 6% and Shy D. cauta 6%. Numbers of these albatrosses were seasonally highest in winter or spring and spatially highest over pelagic water. Black-browed, Yellow-nosed and Shy had highest rates of encounter over the upper slope (depth 200-1500 m) whereas Wandering was encountered most frequently over the lower slope (depth 1500-4200 m). Observation details of four irregular species are reported. The abundance of Black-browed and Yellow-nosed Albatrosses was negatively correlated with sea surface and ambient air temperatures. A preliminary assessment of the latitudinal abundance of common species off New South Wales is presented. Introduction Accounts of the abundance of albatrosses off New South Wales reflect a lack of observations over the continental slope (depth 200-4000 m) and a need for more rigorous census procedures. Marchant (1977) conducted an eleven-month study from the shore at Burrewarra Point, latitude 35 °50 'S. -

BLACK-BROWED ALBATROSS THALASSARCHE Melanophrys FEEDING on a WILSON’S STORM-PETREL OCEANITES OCEANICUS

Seco Pon & Gandini: Wilson’s Storm-Petrel consumed by albatross 77 BLACK-BROWED ALBATROSS THALASSARCHE melanophrys FEEDING ON A WILSON’S STORM-PETREL OCEANITES OCEANICUS JUAN P. SECO PON1,2 & PATRICIA A. GANDINI1,3 1Centro de Investigaciones de Puerto Deseado, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia Austral–Unidad Académica Caleta Olivia, cc 238 Av. Prefectura, s/n (9050), Puerto Deseado Santa Cruz, Argentina ([email protected]) 2Current address: Av. Colón 1908 8o L, Mar del Plata (7600), Buenos Aires, Argentina 3Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas and Wildlife Conservation Society, 2300 Southern Boulevard, Bronx, New York, New York, 10460, USA Received 4 April 2007, accepted 10 November 2007 The diet of Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophrys has in the stomachs of albatrosses. Although in general, penguins tend been studied at several sub-Antarctic colonies (e.g. Ridoux 1994, to be recorded more frequently, prions Pachyptila spp. and diving- Reid et al. 1996, Xavier et al. 2003) and found to consist mainly of petrels Pelecanoides spp. also occur in the diet of albatrosses in the fish, cephalopods and crustaceans. Although this albatross species Southern Ocean. Thus, the occurrence of small seabirds, such as travels vast distances during the non-breeding season (Croxall the Wilson’s Storm-Petrel, in the diet of Black-browed Albatrosses & Wood 2002), the types of food taken remain similar, although is not surprising. prey species and percentages tend to vary (Xavier et al. 2003, Gandini et al. unpubl.). Nevertheless, other prey items—such ACKnowledgements as seabirds, chiefly Spheniscidae and Pelecanoididae (Cherel & Klages 1997) and terns Sterna spp. -

A New Breeding Colony of Blue-Footed Booby Sula Nebouxii at Islote González, Archipelago Islas Desventuradas, Chile

Marín & González: A new Blue-footed Booby breeding colony in Chile 189 A NEW BREEDING COLONY OF BLUE-FOOTED BOOBY SULA NEBOUXII AT ISLOTE GONZÁLEZ, ARCHIPELAGO ISLAS DESVENTURADAS, CHILE MANUEL MARÍN1,2 & RODRIGO GONZÁLEZ3 1Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Section of Ornithology, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA 2Current address: Casilla 15, Melipilla, Chile ([email protected]) 3Santa María 7178, Vitacura, Santiago, Chile Received 13 January 2021, accepted 02 February 2021 ABSTRACT MARÍN, M. & GONZÁLEZ, R. 2021. A new breeding colony of Blue-footed Booby Sula nebouxii at Islote González, Archipelago Islas Desventuradas, Chile. Marine Ornithology 49: 189–192. We describe a new disjunct population of Blue-footed Booby Sula nebouxii at Islote González in the Islas Desventuradas archipelago. Though likely much larger, the population size at the time of our survey was a minimum of 16 breeding pairs. On 14–15 December 2020, two pairs of boobies with nestlings and four pairs with empty nests were found. Likely the species is a recent arrival to the archipelago, perhaps during one of the strong El Niño events between 1970 and 2001 (especially 1982/83, when the species was first recorded in Chile). Blue-footed Booby might also nest on different areas at San Félix Island and some smaller islets around the archipelago, where they would have no nesting-site competition from the larger Masked Booby S. dactylatra. Key words: Blue-footed Booby, Sula nebouxii, breeding, Islas Desventuradas, Chile INTRODUCTION northern coast between 21°54′S and 23°05′S (Guerra 1983). Guerra observed 10 individuals in a 132-km transect while surveying for Within the Sulidae, a widespread and prolific group of piscivorous guano birds and fur seals along the coast.