Chromatic Harmony, Uniform Sequences, and Quantized Voice Leadings Jason Yust Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory Placement Examination (D

SAMPLE Placement Exam for Incoming Grads Name: _______________________ (Compiled by David Bashwiner, University of New Mexico, June 2013) WRITTEN EXAM I. Scales Notate the following scales using accidentals but no key signatures. Write the scale in both ascending and descending forms only if they differ. B major F melodic minor C-sharp harmonic minor II. Key Signatures Notate the following key signatures on both staves. E-flat minor F-sharp major Sample Graduate Theory Placement Examination (D. Bashwiner, UNM, 2013) III. Intervals Identify the specific interval between the given pitches (e.g., m2, M2, d5, P5, A5). Interval: ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ Note: the sharp is on the A, not the G. Interval: ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ IV. Rhythm and Meter Write the following rhythmic series first in 3/4 and then in 6/8. You may have to break larger durations into smaller ones connected by ties. Make sure to use beams and ties to clarify the meter (i.e. divide six-eight bars into two, and divide three-four bars into three). 2 Sample Graduate Theory Placement Examination (D. Bashwiner, UNM, 2013) V. Triads and Seventh Chords A. For each of the following sonorities, indicate the root of the chord, its quality, and its figured bass (being sure to include any necessary accidentals in the figures). For quality of chord use the following abbreviations: M=major, m=minor, d=diminished, A=augmented, MM=major-major (major triad with a major seventh), Mm=major-minor, mm=minor-minor, dm=diminished-minor (half-diminished), dd=fully diminished. Root: Quality: Figured Bass: B. -

Unified Music Theories for General Equal-Temperament Systems

Unified Music Theories for General Equal-Temperament Systems Brandon Tingyeh Wu Research Assistant, Research Center for Information Technology Innovation, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan ABSTRACT Why are white and black piano keys in an octave arranged as they are today? This article examines the relations between abstract algebra and key signature, scales, degrees, and keyboard configurations in general equal-temperament systems. Without confining the study to the twelve-tone equal-temperament (12-TET) system, we propose a set of basic axioms based on musical observations. The axioms may lead to scales that are reasonable both mathematically and musically in any equal- temperament system. We reexamine the mathematical understandings and interpretations of ideas in classical music theory, such as the circle of fifths, enharmonic equivalent, degrees such as the dominant and the subdominant, and the leading tone, and endow them with meaning outside of the 12-TET system. In the process of deriving scales, we create various kinds of sequences to describe facts in music theory, and we name these sequences systematically and unambiguously with the aim to facilitate future research. - 1 - 1. INTRODUCTION Keyboard configuration and combinatorics The concept of key signatures is based on keyboard-like instruments, such as the piano. If all twelve keys in an octave were white, accidentals and key signatures would be meaningless. Therefore, the arrangement of black and white keys is of crucial importance, and keyboard configuration directly affects scales, degrees, key signatures, and even music theory. To debate the key configuration of the twelve- tone equal-temperament (12-TET) system is of little value because the piano keyboard arrangement is considered the foundation of almost all classical music theories. -

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors Richard Bass Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 38, No. 2. (Autumn, 1994), pp. 155-186. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2909%28199423%2938%3A2%3C155%3AMOOAWI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X Journal of Music Theory is currently published by Yale University Department of Music. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/yudm.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Jul 30 09:19:06 2007 MODELS OF OCTATONIC AND WHOLE-TONE INTERACTION: GEORGE CRUMB AND HIS PREDECESSORS Richard Bass A bifurcated view of pitch structure in early twentieth-century music has become more explicit in recent analytic writings. -

Mto.99.5.2.Soderberg

Volume 5, Number 2, March 1999 Copyright © 1999 Society for Music Theory Stephen Soderberg REFERENCE: MTO Vol. 4, No. 3 KEYWORDS: John Clough, Jack Douthett, David Lewin, maximally even set, microtonal music, hyperdiatonic system, Riemann system ABSTRACT: This article is a continuation of White Note Fantasy, Part I, published in MTO Vol. 4, No. 3 (May 1998). Part II combines some of the work done by others on three fundamental aspects of diatonic systems: underlying scale structure, harmonic structure, and basic voice leading. This synthesis allows the recognition of select hyperdiatonic systems which, while lacking some of the simple and direct character of the usual (“historical”) diatonic system, possess a richness and complexity which have yet to be fully exploited. II. A Few Hypertonal Variations 5. Necklaces 6. The usual diatonic as a model for an abstract diatonic system 7. An abstract diatonic system 8. Riemann non-diatonic systems 9. Extension of David Lewin’s Riemann systems References 5. Necklaces [5.1] Consider a symmetric interval string of cardinality n = c+d which contains c interval i’s and d interval j’s. If the i’s and j’s in such a string are additionally spaced as evenly apart from one another as possible, we will call this string a “necklace.” If s is a string in Cn and p is an element of Cn, then the structure ps is a “necklace set.” Thus <iijiij>, <ijijij>, and <ijjijjjijjj> are necklaces, but <iijjii>, <jiijiij>, and <iijj>, while symmetric, are not necklaces. i and j may also be equal, so strings of the 1 of 18 form <iii...> are valid necklaces. -

MTO 20.2: Wild, Vicentino's 31-Tone Compositional Theory

Volume 20, Number 2, June 2014 Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory Genus, Species and Mode in Vicentino’s 31-tone Compositional Theory Jonathan Wild NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.2/mto.14.20.2.wild.php KEYWORDS: Vicentino, enharmonicism, chromaticism, sixteenth century, tuning, genus, species, mode ABSTRACT: This article explores the pitch structures developed by Nicola Vicentino in his 1555 treatise L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica . I examine the rationale for his background gamut of 31 pitch classes, and document the relationships among his accounts of the genera, species, and modes, and between his and earlier accounts. Specially recorded and retuned audio examples illustrate some of the surviving enharmonic and chromatic musical passages. Received February 2014 Table of Contents Introduction [1] Tuning [4] The Archicembalo [8] Genus [10] Enharmonic division of the whole tone [13] Species [15] Mode [28] Composing in the genera [32] Conclusion [35] Introduction [1] In his treatise of 1555, L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica (henceforth L’Antica musica ), the theorist and composer Nicola Vicentino describes a tuning system comprising thirty-one tones to the octave, and presents several excerpts from compositions intended to be sung in that tuning. (1) The rich compositional theory he develops in the treatise, in concert with the few surviving musical passages, offers a tantalizing glimpse of an alternative pathway for musical development, one whose radically augmented pitch materials make possible a vast range of novel melodic gestures and harmonic successions. -

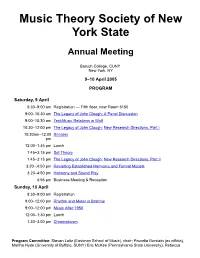

Program and Abstracts for 2005 Meeting

Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting Baruch College, CUNY New York, NY 9–10 April 2005 PROGRAM Saturday, 9 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration — Fifth floor, near Room 5150 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion 9:00–10:30 am TextMusic Relations in Wolf 10:30–12:00 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part I 10:30am–12:00 Scriabin pm 12:00–1:45 pm Lunch 1:45–3:15 pm Set Theory 1:45–3:15 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part II 3:20–;4:50 pm Revisiting Established Harmonic and Formal Models 3:20–4:50 pm Harmony and Sound Play 4:55 pm Business Meeting & Reception Sunday, 10 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration 9:00–12:00 pm Rhythm and Meter in Brahms 9:00–12:00 pm Music After 1950 12:00–1:30 pm Lunch 1:30–3:00 pm Chromaticism Program Committee: Steven Laitz (Eastman School of Music), chair; Poundie Burstein (ex officio), Martha Hyde (University of Buffalo, SUNY) Eric McKee (Pennsylvania State University); Rebecca Jemian (Ithaca College), and Alexandra Vojcic (Juilliard). MTSNYS Home Page | Conference Information Saturday, 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion Chair: Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) Jack Douthett (University at Buffalo, SUNY) Nora Engebretsen (Bowling Green State University) Jonathan Kochavi (Swarthmore, PA) Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) John Clough was a pioneer in the field of scale theory. -

Chromatic Sequences

CHAPTER 30 Melodic and Harmonic Symmetry Combine: Chromatic Sequences Distinctions Between Diatonic and Chromatic Sequences Sequences are paradoxical musical processes. At the surface level they provide rapid harmonic rhythm, yet at a deeper level they function to suspend tonal motion and prolong an underlying harmony. Tonal sequences move up and down the diatonic scale using scale degrees as stepping-stones. In this chapter, we will explore the consequences of transferring the sequential motions you learned in Chapter 17 from the asymmetry of the diatonic scale to the symmetrical tonal patterns of the nineteenth century. You will likely notice many similarities of behavior between these new chromatic sequences and the old diatonic ones, but there are differences as well. For instance, the stepping-stones for chromatic sequences are no longer the major and minor scales. Furthermore, the chord qualities of each individual harmony inside a chromatic sequence tend to exhibit more homogeneity. Whereas in the past you may have expected major, minor, and diminished chords to alternate inside a diatonic sequence, in the chromatic realm it is not uncommon for all the chords in a sequence to manifest the same quality. EXAMPLE 30.1 Comparison of Diatonic and Chromatic Forms of the D3 ("Pachelbel") Sequence A. 624 CHAPTER 30 MELODIC AND HARMONIC SYMMETRY COMBINE 625 B. Consider Example 30.1A, which contains the D3 ( -4/ +2)-or "descending 5-6"-sequence. The sequence is strongly goal directed (progressing to ii) and diatonic (its harmonies are diatonic to G major). Chord qualities and distances are not consistent, since they conform to the asymmetry of G major. -

The Perceptual Attraction of Pre-Dominant Chords 1

Running Head: THE PERCEPTUAL ATTRACTION OF PRE-DOMINANT CHORDS 1 The Perceptual Attraction of Pre-Dominant Chords Jenine Brown1, Daphne Tan2, David John Baker3 1Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University 2University of Toronto 3Goldsmiths, University of London [ACCEPTED AT MUSIC PERCEPTION IN APRIL 2021] Author Note Jenine Brown, Department of Music Theory, Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA; Daphne Tan, Faculty of Music, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; David John Baker, Department of Computing, Goldsmiths, University of London, London, United Kingdom. Corresponding Author: Jenine Brown, Peabody Institute of The John Hopkins University, 1 E. Mt. Vernon Pl., Baltimore, MD, 21202, [email protected] 1 THE PERCEPTUAL ATTRACTION OF PRE-DOMINANT CHORDS 2 Abstract Among the three primary tonal functions described in modern theory textbooks, the pre-dominant has the highest number of representative chords. We posit that one unifying feature of the pre-dominant function is its attraction to V, and the experiment reported here investigates factors that may contribute to this perception. Participants were junior/senior music majors, freshman music majors, and people from the general population recruited on Prolific.co. In each trial four Shepard-tone sounds in the key of C were presented: 1) the tonic note, 2) one of 31 different chords, 3) the dominant triad, and 4) the tonic note. Participants rated the strength of attraction between the second and third chords. Across all individuals, diatonic and chromatic pre-dominant chords were rated significantly higher than non-pre-dominant chords and bridge chords. Further, music theory training moderated this relationship, with individuals with more theory training rating pre-dominant chords as being more attracted to the dominant. -

Appendix A: Mathematical Preliminaries

Appendix A: Mathematical Preliminaries Definition A1. Cartesian Product Let X and Y be two non-empty sets. The Cartesian product of X and Y, denoted X Â Y, is the set of all ordered pairs, a member of X followed by a member of Y. That is, ÈÉ X Â Y ¼ ðÞx, y x 2 X, y ∈ Y : Example A2. Let X ¼ {0, 1}, Y ¼ {x, y, z}. Then the Cartesian product X Â Y of X and Y is fgðÞ0, x ,0,ðÞy ,0,ðÞz ,1,ðÞx ,1,ðÞy ,1,ðÞz : Definition A3. Relation Let X and Y be two non-empty sets. A subset of X Â Y is a relation from X to Y; a subset of X Â X is a relation in X. Example A4. Let X ¼ {0, 1}, Y ¼ {x, y, z}. Then ÈÉÀ Á À Á À Á R ¼ ðÞ0, x , 1, x , 1, y , 1, z , R0 ¼ ∅, are relations from X to Y.(R0 is a relation because the empty set ∅ is a subset of every set.) Moreover, R00 ¼ fgðÞ0, 0 ,1,0ðÞ,1,1ðÞ is a relation in X. Definition A5. Function Let X and Y be two non-empty sets. E. Agmon, The Languages of Western Tonality, Computational Music Science, 265 DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-39587-1, © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 266 Appendix A: Mathematical Preliminaries A function f from X into Y is a subset of X Â Y (i.e., a relation from X to Y) with the following property. For every x ∈ X, there exists exactly one y ∈ Y, such that (x, y) ∈ f. -

Transfer Theory Placement Exam Guide (Pdf)

2016-17 GRADUATE/ transfer THEORY PLACEMENT EXAM guide! Texas woman’s university ! ! 1 2016-17 GRADUATE/transferTHEORY PLACEMENTEXAMguide This! guide is meant to help graduate and transfer students prepare for the Graduate/ Transfer Theory Placement Exam. This evaluation is meant to ensure that students have competence in basic tonal harmony. There are two parts to the exam: written and aural. Part One: Written Part Two: Aural ‣ Four voice part-writing to a ‣ Melodic dictation of a given figured bass diatonic melody ‣ Harmonic analysis using ‣ Harmonic Dictation of a Roman numerals diatonic progression, ‣ Transpose a notated notating the soprano, bass, passage to a new key and Roman numerals ‣ Harmonization of a simple ‣ Sightsinging of a melody diatonic melody that contains some functional chromaticism ! Students must achieve a 75% on both the aural and written components of the exam. If a passing score is not received on one or both sections of the exam, the student may be !required to take remedial coursework. Recommended review materials include most of the commonly used undergraduate music theory texts such as: Tonal Harmony by Koska, Payne, and Almén, The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis by Clendinning and Marvin, and Harmony in Context by Francoli. The exam is given prior to the beginning of both the Fall and Spring Semesters. Please check the TWU MUSIc website (www.twu.edu/music) ! for the exact date and time. ! For further information, contact: Dr. Paul Thomas Assistant Professor of Music Theory and Composition [email protected] 2 2016-17 ! ! ! ! table of Contents ! ! ! ! ! 04 Part-Writing ! ! ! ! ! 08 melody harmonization ! ! ! ! ! 13 transposition ! ! ! ! ! 17 Analysis ! ! ! ! ! 21 melodic dictation ! ! ! ! ! harmonic dictation ! 24 ! ! ! ! Sightsinging examples ! 28 ! ! ! 31 terms ! ! ! ! ! 32 online resources ! 3 PART-Writing Part-writing !Realize the following figured bass in four voices. -

Expanded Tonality: the Rt Eatment of Upper and Lower Leading Tones As Evidenced in Sonata "Undine,” IV by Carl Reinecke Joshua Blizzard University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-13-2007 Expanded Tonality: The rT eatment of Upper and Lower Leading Tones As Evidenced in Sonata "Undine,” IV by Carl Reinecke Joshua Blizzard University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Blizzard, Joshua, "Expanded Tonality: The rT eatment of Upper and Lower Leading Tones As Evidenced in Sonata "Undine,” IV by Carl Reinecke" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/638 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Expanded Tonality: The Treatment of Upper and Lower Leading Tones As Evidenced in Sonata "Undine,” IV by Carl Reinecke by Joshua Blizzard A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music College of Visual and Performing Arts University of South Florida Major Professor: Ann Hawkins, M.A. Kim McCormick, D.M.A. David A. Williams, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 13, 2007 Keywords: tonic substitution, wedge, prolongation, delayed resolution, chromaticism © Copyright 2007, Joshua Blizzard Dedication To my wife for her tireless support of me both emotionally and monetarily, to my Aunt Susie who played a significant role in my musical development from my youth, to my parents who worked to instill a sense of discipline in my studies, and, ultimately, to the glory of God, without whom nothing is possible. -

MTO 22.4: Gotham, Pitch Properties of the Pedal Harp

Volume 22, Number 4, December 2016 Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory Pitch Properties of the Pedal Harp, with an Interactive Guide * Mark R. H. Gotham and Iain A. D. Gunn KEYWORDS: harp, pitch, pitch-class set theory, composition, analysis ABSTRACT: This article is aimed at two groups of readers. First, we present an interactive guide to pitch on the pedal harp for anyone wishing to teach or learn about harp pedaling and its associated pitch possibilities. We originally created this in response to a pedagogical need for such a resource in the teaching of composition and orchestration. Secondly, for composers and theorists seeking a more comprehensive understanding of what can be done on this unique instrument, we present a range of empirical-theoretical observations about the properties and prevalence of pitch structures on the pedal harp and the routes among them. This is particularly relevant to those interested in extended-tonal and atonal repertoires. A concluding section discusses prospective theoretical developments and analytical applications. 1 of 21 Received June 2016 I. Introduction [1.1] Most instruments have a relatively clear pitch universe: some have easy access to continuous pitch (unfretted string instruments, voices, the trombone), others are constrained by the 12-tone chromatic scale (most keyboards), and still others are limited to notes of the diatonic or pentatonic scales (many non-Western-orchestral members of the xylophone family). The pedal harp, by contrast, falls somewhere between those last two categories: it is organized around a diatonic configuration, but can reach all 12 notes of the chromatic scale, and most (but not all) pitch-class sets.