Volumes Published (2006)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Icelandic Folklore

i ICELANDIC FOLKLORE AND THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF RELIGIOUS CHANGE ii BORDERLINES approaches,Borderlines methodologies,welcomes monographs or theories and from edited the socialcollections sciences, that, health while studies, firmly androoted the in late antique, medieval, and early modern periods, are “edgy” and may introduce sciences. Typically, volumes are theoretically aware whilst introducing novel approaches to topics of key interest to scholars of the pre-modern past. iii ICELANDIC FOLKLORE AND THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF RELIGIOUS CHANGE by ERIC SHANE BRYAN iv We have all forgotten our names. — G. K. Chesterton Commons licence CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. This work is licensed under Creative British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. © 2021, Arc Humanities Press, Leeds The author asserts their moral right to be identi�ied as the author of this work. Permission to use brief excerpts from this work in scholarly and educational works is hereby granted determinedprovided that to thebe “fair source use” is under acknowledged. Section 107 Any of theuse U.S.of material Copyright in Act this September work that 2010 is an Page exception 2 or that or limitation covered by Article 5 of the European Union’s Copyright Directive (2001/ 29/ EC) or would be 94– 553) does not require the Publisher’s permission. satis�ies the conditions speci�ied in Section 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act (17 USC §108, as revised by P.L. ISBN (HB): 9781641893756 ISBN (PB): 9781641894654 eISBN (PDF): 9781641893763 www.arc- humanities.org print-on-demand technology. -

Bacheloroppgave I Historie LHIS370 Karina Eieland

Kandidatnummer: 2304 Sidebaner som del av norsk jernbanestrategi Setesdalsbanen som eksempel Karine Narvestad Eieland Bacheloroppgave i historie, våren 2021 LHIS370 Universitetet i Stavanger Institutt for kultur- og språkvitenskap I Kandidatnummer: 2304 Innholdsfortegnelse 1.0 Innledning ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Bakgrunn .......................................................................................................................... 2 2.0 Den norske jernbaneutbygginga på 1800-tallet .................................................................... 6 2.1 Stambane – sidebane: en begrepsavklaring ...................................................................... 6 2.2 Hovedbanen – den første jernbanen i landet .................................................................... 7 2.3 Jernbanepolitikken i 1860- og 70-åra ............................................................................... 8 2.3.1 "Det norske system" ................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Jernbanepolitikken i 1880- og 90-åra ............................................................................. 11 2.4.1 Veien mot et statlig jernbanesystem ........................................................................ 11 3.0 Setesdalsbanen ................................................................................................................... 13 3.1 Setesdal før jernbanen -

Bibliography

Bibliography Editions and Translations of Primary Sources Ågrip or Noregs kongesoger. Translated by Gustav Indrebø. Oslo: Det norske samlaget, 1973. Acta et processus canonizationis b. Birgitte. Edited by Isak Collijn. Samlingar utgivna av Svenska fornskriftsällskapet, Ser. 2, Latinska skrifter. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell boktryckeri, 1924–1931. Acta sanctorum. 68 vols. Edited by Johannes Bollandus and Godefridus Henschenius. Antwerp & Brussels: Société des Bollandistes, 1643–1940. Adalbold II of Utrecht. Vita Henrici II imperatoris. Edited by Georg Waitz. MGH. Hannover: Hahnsche Buchhandlung, 1841. 679–95. Adam of Bremen. Mag. Adami gesta Hammenbergensis Ecclesias Pontificum. Edited by Johann Martin Lappenberg. MGH SS, 7. Hanover, 1846. 267–389. ———. Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum. Edited by Bernard Schmeidler. MGH. Hannover & Leipzig: Hahnsche Buchhandlung, 1917. ———. The History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen. Translated by Francis Joseph Tschan. New York: Columbia University Press, 1959. Ágrip af Nóregskonunga sǫgum. Fagrskinna – Nóregs konunga tal. Edited by Bjarni Einarsson. Íslenzk Fornrit, 29. Reykjavík: Hið islenzká fornritafelag,́ 1985. Ágrip af Nóregskonungasǫgum.InText Series. Edited by Matthew James Driscoll. 2nd ed. A Twelfth-Century Synoptic History of the Kings of Norway, 10. London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 2008. Akershusregisteret af 1622. Edited by G. Tank. Den norske historiske Kildeskriftkommission. Kristiania: Grøndahl & Søns boktryggeri, 1916. Alain de Lille. De planctu naturae. PL, 210. col. 579A. ———. De planctu naturae. Translated by G.R. Evans. Alan of Lille: The Frontiers of Theology in the Later Twelfth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. Albert of Aachen. Historia Ierosolimitana. Edited and translated by Susan B. Edgington. Oxford Medieval Texts. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007. Albert of Stade. -

A Master's Thesis in Nordic Vikings and Medieval Culture

The Leaders King Sverre and King Haakon Analysis of King Sverre Sigurdsson and King Haakon Haakonsson in Sverris Saga and Haakonar Saga Haakonarsonar through Max Weber’s and John Gardner’s models A Master’s Thesis in Nordic Vikings and Medieval Culture By Ismael Osornio Duran The Center for Nordic Viking and Medieval Culture The Faculty of Arts University of Oslo Spring 2004 Oslo, Norway 1 Acknowledgments Thanks with all my heart to God and Norway for the great opportunity that I had to live this enriching stage of my life, on my personal growth and to the beautiful people that I have known. Permanently I will keep these experiences in my life. Thanks to my wife and soul mate Nira who gave me the opportunity to share dreams and life. Without her, nothing would have been possible. Thanks to my parents and brother, for their confidence, support and unconditional love. To my huge family for their encourage and motivation. Thanks to my editors Elder Benito and Elder Kleist. I would like to express my gratitude and honor to the Senter for Studier i Vikingtid og Nordisk Middelalder at the University of Oslo especially to my advisor Jón Viðar Sigurðsson for all his comments, patience, observations and advises to make possible this dissertation. 2 Introduction The leadership of the Norwegian Kings during the Medieval ‘Civil War’ plays a prominent part in social, political and economical life in high Medieval Norway. The objective of the present dissertation discusses how King Sverre Sigurdsson (1177-1202) and Haakon Haakonsson (1217-1263) are depicted in their Sagas. -

1 Historikeren Medlemsblad for Den Norske Historiske Forening 3.2015

Medlemsblad for Den Norske Historikeren Historiske Forening 3.2015 1 Innhold 6......... HIFO-nytt Referat fra årsmøtet i HIFO 2015 5 Historikerne og fremtiden Erling Sandmo 8 Årets prisvinnere Henrik Olav Mathiesen 11 Redaksjonen Historiske nyheter 36......... HBR og transatlantisk migrasjon Hilde L. Sommerseth 14 Da prestefrua Caroline «Linka» Preus var på vei over Atlanteren med mannen Herman i 1851, Om dilettanteri og hårsårhet – Risørs historie Erik Tobias Taube 22 noterte hun i dagboka at på fødselsdagen hennes ville Herman «servere rype for meg», men det Metrolinje ved verdensarv Morten Haave 29 hadde det ikke blitt noe av: «den uærlige hermetikkfabrikanten hadde gitt oss en fordervet fugl». På 1800-tallet var Amerika i ferd med å fylles opp av immigranter, slik som ekteparet Preus Lokallag – og også av hermetikk. Historikeren Patricia Nelson Limerick gjengir ordene til en annen kvinne som flyttet ut til den amerikanske vesten i 1883: «Everyone in the country lived out of Vest-Oppland: Rekord for HIFO-arrangement? 31 Morten Haave cans and you would see a great heap of them outside every little shack». Som ressurs var hermetikk noe tilnærmet en revolusjon, noe militær- og krigshistorikere Reisebrevet vil kunne bekrefte. Medievalisme og nasjonalisme Karl Christian Alvestad 33 Hermetikkboksene som pryder forsiden av denne utgaven av Historikeren, kommer hovedsakelig fra Stavanger. Her var det også at norske historikere samlet seg i sommer, og de Seniors perspektiv kunne besøke «Norsk hermetikkmuseum» på en av ekskursjonene under årets historiedager. Tema for årets konferanse var nemlig ressurser: energi, makt og mennesker. Ressurser kan Intervju med Terje Talsnes Vibeke Kieding Banik 38 være håndgripelige, som immigranter eller hermetikk, eller abstrakte, som tid. -

Årsmelding 1976

UNIVERSITETET I BERGEN ÅRSMELDING 1976 FRA DET AKADEMISKE KOLLEGIUM UTGITT AV UNIVERSITETSDIREKTØREN REDAKSJON AVDELING FOR OPPLYSNINGSVIRKSOMHET Qmslagsbilde: De prekliniske institutter, Arstadvollen. Bygningen ble tatt i bruk høstsemesterct 1966, og den er tegnet av arkitektenc MNAL Gunnar Fougner og Einar MyklcVust. Anatomisk, Biokjemisk og Fysiologisk institutt har sine lokaler her. ISBN-82-7127U30-3 Innhold Det akademiske kollegium 5 Bergens Museumsråd 5 Universitetets personale 5 Minneord 5 Avskjed i nåde 6 Utncvninger av professorcr og dosentcr 7 Administrasjonen 14 Oversikt over personalet 17 Forholdstall 19 Studerende ved Universitetet i Bergen 20 Nye studenter 1976 20 Registrerte studentcr 22 Fagoversikt 22 Eksamenet' og grader 28 Doktorgrader 28 Licentiatgrader 29 Magistergrader 30 Hislorisk-filosofisk embetseksamen 32 Matematisk-naturvitenskapelig embetseksamen 40 Samfunnsvitenskapelig embetseksamen 47 Psykologisk embetseksamen 49 Juridisk embetseksamen 52 Medisinsk embetseksamen 53 Odontologisk embetseksamen 54 Bygninger 55 Publikasjoncr 55 Årsfesten 55 De vitenskapelige samlingene 56 Representasjon 57 Rektors representasjon 57 Representasjon i styrer og utvalg 57 Legaler og fond dl! Legaler og fond som luner lii eller blir Myri av L'niviiMt ni i Bergen i>2 Utdeling av legaler og fond dl Æresbevisninger ... 6't Prisoppgåver d*i Gåver ti') Regnskap 7(1 Det historisk-tilosofiske fakultet 75 De enkelte instituttet- 75 Det materuatisk-naturvitcnskapeligc fakultet 113 De enkelte institutter 113 Det medisinske fakultet 198 De enkelte institutter 198 Det odontologiske fakultet 273 De enkelte institutter 273 Det samfunnsvitenskapelige fakultet 284 De enkelte institutter 284 Avdeling for elektronisk databehandling 312 Avdeling for helsekontroll 318 Det pedagogiske seminar 319 Opplysningsarbeid 323 Sommerkurs 329 Universitetsbiblioteket 333 DET AKADEMISKE KOLLEGIUM UNIVERSITETETS PERSONALE Professor Arnc-Johan Henrichsen, rektor. -

Ragnar Frisch and the Postwar Norwegian Economy · Econ Journal Watch: History of Economic Thought,Ragnar Frisch,Norway,Scandina

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5819 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 11(1) January 2014: 46-80 Ragnar Frisch and the Postwar Norwegian Economy Arild Sæther1 and Ib E. Eriksen2 LINK TO ABSTRACT In Norwegian academic life the memorial Nobel Prize winner Ragnar Frisch (1895–1973) is still a major figure, and he is universally recognized as a great economist. Here the story will be told how he built up the Oslo School of economic teaching and research, and how the Oslo School influenced economic policy in the small, homogeneous, and relatively culturally insular country of Norway. That influence moved the Norwegian economy toward economic planning. During the postwar decades the Norwegian economy achieved economic growth rates similar to other OECD countries, but with significantly higher investment ratios. The Norwegian economy was getting less ‘bang for its buck,’ with the result being lower rates of consumption. At the end of the 1970s the lagging economic performance impelled a change. Much of the present article is a reworking of materials that we have published previously, some with our late colleague Tore Jørgen Hanisch, particularly articles in the Nordic Journal of Political Economy (Eriksen, Hanisch, and Sæther 2007; Eriksen and Sæther 2010a). This article hopes to bring the story and its lessons to a wider audience.3 Translations from Norwegian sources are our own, unless otherwise noted. 1. Agder Academy of Sciences and Letters, 4604 Kristiansand, Norway. 2. School of Business and Law, University of Agder, 4604 Kristiansand, Norway. 3. The present article incorporates some material also used in our ideological profile of Frisch (Sæther and Eriksen 2013) that appeared in the previous issue of Econ Journal Watch. -

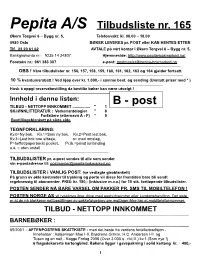

Tilbudsliste Nr

Pepita A/S Tilbudsliste nr. 165 Økern Torgvei 6 – Bygg nr. 5, Telefonvakt: kl. 08.00 – 18.00 0580 Oslo BØKER LEVERES pr. POST eller KAN HENTES ETTER Tlf. 22 20 61 62 AVTALE på vårt kontor i Økern Torgvei 6 – Bygg nr. 5, Bankgirokonto nr.: 9235 14 34807 Hjemmeside: http://www.pepita-bokmarked.no/ Foretaks nr.: 961 383 307 e-post: [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ OBS ! Våre tilbudslister nr. 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163 og 164 gjelder fortsatt. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 % kvantumsrabatt ! Ved kjøp over kr. 1.000,- i samme best. og sending (Unntatt priser med * ) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Husk å oppgi reservebestilling da bestilte bøker kan være utsolgt ! ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Innhold i denne listen: B - post TILBUD - NETTOPP INNKOMMET ................ " 1 SKJØNNLITTERATUR : Verker/antologier " 8 Forfattere (etternavn A - F) ” 9 Bestillingsblankett på siste side -

Thesis.Pdf (7.136Mb)

UiT Norges arktiske universitet Fakultet for humaniora, samfunnsvitenskap og lærerutdanning Migrasjon, sild, olje og urbanisering Olav Tysdal Avhandling levert for graden doctor philosophiae - november 2019 1 Migranter er jenter som flytter, gutter som flytter, voksne som flytter, familier som flytter. er barn som flytter, ungdom som flytter, de midt i livet som flytter, eldre som flytter. flytter over korte avstander, migranter flytter over lange avstander. flytter innenfor administrative enheter, migranter krysser administrative grenser. er internmigranter som flytter innenfor et lands grenser. er immigranter som krysser grenser og flytter til nye land, emigranter krysser grenser og flytter fra land. flytter for å redde livene sine - flyktninger er også migranter. flytter for å komme unna etnisk diskriminering. flytter for å komme vekk fra politisk eller religiøs undertrykking og forfølgelse. tar livsskjebnen i egne hender – de sekulariserer håpet. flytter for å skaffe et bedre liv for seg og sine. flytter på veien oppover en karrierestige. flytter på grunn av giftermål – praktisk- eller kjærlighetsmotivert. flytter på grunn av klima og klimaforandringer. flytter av hundrevis andre individuelle eller kollektive årsaker. Forsideillustrasjon Sildesalting i sjøhuset til kjøpmann Schanche Monsen i Stavanger. Utsnitt av maleri av Philip Kriebel fra omkring 1840. Etter å ha vært borte i flere tiår, kom vårsilda tilbake til Vestlandskysten i 1808. Eksport av vårsild fikk stor økonomisk betydning. Fisket var viktig fram til 1870-årene. Foto: Stavanger Museum 2 Forord Arbeidet med denne avhandlingen har strukket seg over mange år. Ikke overraskende har det vekslet mellom perioder med god framdrift, og det motsatte, med motbakker og forsinket progresjonen som resultat. Arbeidet har heller ikke vært et sololøp. -

In Memoriam: Dr. Arne Odd Johnsen, Norwegian Historian

72 IN MEMORIAM: DR. ARNE ODD JOHNSEN, NORWEGIAN HISTORIAN C de Jong University of South Africa Arne Odd Johnsen was born at Agder, Norway, on 3 December 1909 as the son of Oscar Albert Johnsen. Oscar became a professor of Norwegian history at the Universi- ty of Oslo and author of several books and many articles. His work that is best known abroad is Norwegzsche Wirtschaftsgeschichte (Norwegian economic history, 1939), one of the series of books with surveys of the economic history of different countries, published by Gustav Fischer at Jena, Germany. Arne was inspired by the historical studies, library and career of his father. He became an even more many-sided and productive historian than his father was. As the son of a maritime nation he was attracted by the maritime and economic history of Norway. He was very proud of his mother's grandfather, sea captain Even Tollefsen, who was the first captain to bring a ship with a bulk cargo of petroleum from the United States to Europe. Arne published an article on this pioneer. He registered as a student in Oslo in 1928 and received his Master's degree in 1936 with a thesis on Tonsberg during the economic depression in the first half of the 19th century. He studied at the Ecole des Chartes, Sorbonne, and the College de France, in Paris from 1937 to 193~. There he started his studies in his second field of historic interest: Norway during the Middle Ages. In 1939 he became a student at the University of Oslo until 1951 with an inter- ruption during the German occupation, 1943 -1945. -

An Anti-‐Semitic Slaughter Law? the Origins of the Norwegian

Andreas Snildal An Anti-Semitic Slaughter Law? The Origins of the Norwegian Prohibition of Jewish Religious Slaughter c. 1890–1930 Dissertation for the Degree of Philosophiae Doctor Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo 2014 2 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Einhart Lorenz, who first suggested the Norwegian controversy on Jewish religious slaughter as a suiting theme for a doctoral dissertation. Without his support and guidance, the present dissertation could not have been written. I also thank Lars Lien of the Center for Studies of the Holocaust and Religious Minorities, Oslo, for generously sharing with me some of the source material collected in connection with his own doctoral work. The Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History has offered me excellent working conditions for three years, and I would thank in particular Professor Gro Hagemann for encouragement and not least for thought-provoking thesis seminars. A highlight in this respect was the seminar that she arranged at the Centre Franco-Norvégien en Sciences Sociales et Humaines in Paris in September 2012. I would also like to thank the Centre and its staff for having hosted me on other occasions. Fellow doctoral candidates at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History have made these past three years both socially and scholarly stimulating. In this regard, I am indebted particularly to Chalak Kaveh and Margaretha Adriana van Es, whose comments on my drafts have been of great help. ‘Extra- curricular’ projects conducted together with friends and former colleagues Ernst Hugo Bjerke and Tor Ivar Hansen have been welcome diversions from dissertation work.