Single Sideband Modulation for Digital Fiber Optic Communication Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optical Single Sideband for Broadband and Subcarrier Systems

University of Alberta Optical Single Sideband for Broadband And Subcarrier Systems Robert James Davies 0 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillrnent of the requirernents for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Electrical And Computer Engineering Edmonton, AIberta Spring 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KlA ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Yom iUe Votre relérence Our iSie Norre reference The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otheMrise de celle-ci ne doivent être Unprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract Radio systems are being deployed for broadband residential telecommunication services such as broadcast, wideband lntemet and video on demand. Justification for radio delivery centers on mitigation of problems inherent in subscriber loop upgrades such as Fiber to the Home (WH)and Hybrid Fiber Coax (HFC). -

Chapter 1 Experiment-8

Chapter 1 Experiment-8 1.1 Single Sideband Suppressed Carrier Mod- ulation 1.1.1 Objective This experiment deals with the basic of Single Side Band Suppressed Carrier (SSB SC) modulation, and demodulation techniques for analog commu- nication.− The student will learn the basic concepts of SSB modulation and using the theoretical knowledge of courses. Upon completion of the experi- ment, the student will: *UnderstandSSB modulation and the difference between SSB and DSB modulation * Learn how to construct SSB modulators * Learn how to construct SSB demodulators * Examine the I Q modulator as SSB modulator. * Possess the necessary tools to evaluate and compare the SSB SC modulation to DSB SC and DSB_TC performance of systems. − − 1.1.2 Prelab Exercise 1.Using Matlab or equivalent mathematics software, show graphically the frequency domain of SSB SC modulated signal (see equation-2) . Which of the sign is given for USB− and which for LSB. 1 2 CHAPTER 1. EXPERIMENT-8 2. Draw a block diagram and explain two method to generate SSB SC signal. − 3. Draw a block diagram and explain two method to demodulate SSB SC signal. − 4. According to the shape of the low pass filter (see appendix-1), choose a carrier frequency and modulation frequency in order to implement LSB SSB modulator, with minimun of 30 dB attenuation of the USB component. 1.1.3 Background Theory SSB Modulation DEFINITION: An upper single sideband (USSB) signal has a zero-valued spectrum for f <fcwhere fc, is the carrier frequency. A lower single| | sideband (LSSB) signal has a zero-valued spectrum for f >fc where fc, is the carrier frequency. -

UNIT V- SPREAD SPECTRUM MODULATION Introduction

UNIT V- SPREAD SPECTRUM MODULATION Introduction: Initially developed for military applications during II world war, that was less sensitive to intentional interference or jamming by third parties. Spread spectrum technology has blossomed into one of the fundamental building blocks in current and next-generation wireless systems. Problem of radio transmission Narrow band can be wiped out due to interference. To disrupt the communication, the adversary needs to do two things, (a) to detect that a transmission is taking place and (b) to transmit a jamming signal which is designed to confuse the receiver. Solution A spread spectrum system is therefore designed to make these tasks as difficult as possible. Firstly, the transmitted signal should be difficult to detect by an adversary/jammer, i.e., the signal should have a low probability of intercept (LPI). Secondly, the signal should be difficult to disturb with a jamming signal, i.e., the transmitted signal should possess an anti-jamming (AJ) property Remedy spread the narrow band signal into a broad band to protect against interference In a digital communication system the primary resources are Bandwidth and Power. The study of digital communication system deals with efficient utilization of these two resources, but there are situations where it is necessary to sacrifice their efficient utilization in order to meet certain other design objectives. For example to provide a form of secure communication (i.e. the transmitted signal is not easily detected or recognized by unwanted listeners) the bandwidth of the transmitted signal is increased in excess of the minimum bandwidth necessary to transmit it. -

CS647: Advanced Topics in Wireless Networks Basics

CS647: Advanced Topics in Wireless Networks Basics of Wireless Transmission Part II Drs. Baruch Awerbuch & Amitabh Mishra Computer Science Department Johns Hopkins University CS 647 2.1 Antenna Gain For a circular reflector antenna G = η ( π D / λ )2 η = net efficiency (depends on the electric field distribution over the antenna aperture, losses such as ohmic heating , typically 0.55) D = diameter, thus, G = η (π D f /c )2, c = λ f (c is speed of light) Example: Antenna with diameter = 2 m, frequency = 6 GHz, wavelength = 0.05 m G = 39.4 dB Frequency = 14 GHz, same diameter, wavelength = 0.021 m G = 46.9 dB * Higher the frequency, higher the gain for the same size antenna CS 647 2.2 Path Loss (Free-space) Definition of path loss LP : Pt LP = , Pr Path Loss in Free-space: 2 2 Lf =(4π d/λ) = (4π f cd/c ) LPF (dB) = 32.45+ 20log10 fc (MHz) + 20log10 d(km), where fc is the carrier frequency This shows greater the fc, more is the loss. CS 647 2.3 Example of Path Loss (Free-space) Path Loss in Free-space 130 120 fc=150MHz (dB) f f =200MHz 110 c f =400MHz 100 c fc=800MHz 90 fc=1000MHz 80 Path Loss L fc=1500MHz 70 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Distance d (km) CS 647 2.4 Land Propagation The received signal power: G G P P = t r t r L L is the propagation loss in the channel, i.e., L = LP LS LF Fast fading Slow fading (Shadowing) Path loss CS 647 2.5 Propagation Loss Fast Fading (Short-term fading) Slow Fading (Long-term fading) Signal Strength (dB) Path Loss Distance CS 647 2.6 Path Loss (Land Propagation) Simplest Formula: -α Lp = A d where A and -

3 Characterization of Communication Signals and Systems

63 3 Characterization of Communication Signals and Systems 3.1 Representation of Bandpass Signals and Systems Narrowband communication signals are often transmitted using some type of carrier modulation. The resulting transmit signal s(t) has passband character, i.e., the bandwidth B of its spectrum S(f) = s(t) is much smaller F{ } than the carrier frequency fc. S(f) B f f f − c c We are interested in a representation for s(t) that is independent of the carrier frequency fc. This will lead us to the so–called equiv- alent (complex) baseband representation of signals and systems. Schober: Signal Detection and Estimation 64 3.1.1 Equivalent Complex Baseband Representation of Band- pass Signals Given: Real–valued bandpass signal s(t) with spectrum S(f) = s(t) F{ } Analytic Signal s+(t) In our quest to find the equivalent baseband representation of s(t), we first suppress all negative frequencies in S(f), since S(f) = S( f) is valid. − The spectrum S+(f) of the resulting so–called analytic signal s+(t) is defined as S (f) = s (t) =2 u(f)S(f), + F{ + } where u(f) is the unit step function 0, f < 0 u(f) = 1/2, f =0 . 1, f > 0 u(f) 1 1/2 f Schober: Signal Detection and Estimation 65 The analytic signal can be expressed as 1 s+(t) = − S+(f) F 1{ } = − 2 u(f)S(f) F 1{ } 1 = − 2 u(f) − S(f) F { } ∗ F { } 1 The inverse Fourier transform of − 2 u(f) is given by F { } 1 j − 2 u(f) = δ(t) + . -

Radio Communications in the Digital Age

Radio Communications In the Digital Age Volume 1 HF TECHNOLOGY Edition 2 First Edition: September 1996 Second Edition: October 2005 © Harris Corporation 2005 All rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-94476 Harris Corporation, RF Communications Division Radio Communications in the Digital Age Volume One: HF Technology, Edition 2 Printed in USA © 10/05 R.O. 10K B1006A All Harris RF Communications products and systems included herein are registered trademarks of the Harris Corporation. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...............................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 PRINCIPLES OF RADIO COMMUNICATIONS .....................................6 CHAPTER 2 THE IONOSPHERE AND HF RADIO PROPAGATION..........................16 CHAPTER 3 ELEMENTS IN AN HF RADIO ..........................................................24 CHAPTER 4 NOISE AND INTERFERENCE............................................................36 CHAPTER 5 HF MODEMS .................................................................................40 CHAPTER 6 AUTOMATIC LINK ESTABLISHMENT (ALE) TECHNOLOGY...............48 CHAPTER 7 DIGITAL VOICE ..............................................................................55 CHAPTER 8 DATA SYSTEMS .............................................................................59 CHAPTER 9 SECURING COMMUNICATIONS.....................................................71 CHAPTER 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS .....................................................................77 APPENDIX A STANDARDS -

Demodulation of Chaos Phase Modulation Spread Spectrum Signals Using Machine Learning Methods and Its Evaluation for Underwater Acoustic Communication

sensors Article Demodulation of Chaos Phase Modulation Spread Spectrum Signals Using Machine Learning Methods and Its Evaluation for Underwater Acoustic Communication Chao Li 1,2,*, Franck Marzani 3 and Fan Yang 3 1 State Key Laboratory of Acoustics, Institute of Acoustics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China 3 LE2I EA7508, Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté, 21078 Dijon, France; [email protected] (F.M.); [email protected] (F.Y.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 September 2018; Accepted: 28 November 2018; Published: 1 December 2018 Abstract: The chaos phase modulation sequences consist of complex sequences with a constant envelope, which has recently been used for direct-sequence spread spectrum underwater acoustic communication. It is considered an ideal spreading code for its benefits in terms of large code resource quantity, nice correlation characteristics and high security. However, demodulating this underwater communication signal is a challenging job due to complex underwater environments. This paper addresses this problem as a target classification task and conceives a machine learning-based demodulation scheme. The proposed solution is implemented and optimized on a multi-core center processing unit (CPU) platform, then evaluated with replay simulation datasets. In the experiments, time variation, multi-path effect, propagation loss and random noise were considered as distortions. According to the results, compared to the reference algorithms, our method has greater reliability with better temporal efficiency performance. Keywords: underwater acoustic communication; direct sequence spread spectrum; chaos phase modulation sequence; partial least square regression; machine learning 1. Introduction The underwater acoustic communication has always been a crucial research topic [1–6]. -

2 the Wireless Channel

CHAPTER 2 The wireless channel A good understanding of the wireless channel, its key physical parameters and the modeling issues, lays the foundation for the rest of the book. This is the goal of this chapter. A defining characteristic of the mobile wireless channel is the variations of the channel strength over time and over frequency. The variations can be roughly divided into two types (Figure 2.1): • Large-scale fading, due to path loss of signal as a function of distance and shadowing by large objects such as buildings and hills. This occurs as the mobile moves through a distance of the order of the cell size, and is typically frequency independent. • Small-scale fading, due to the constructive and destructive interference of the multiple signal paths between the transmitter and receiver. This occurs at the spatialscaleoftheorderofthecarrierwavelength,andisfrequencydependent. We will talk about both types of fading in this chapter, but with more emphasis on the latter. Large-scale fading is more relevant to issues such as cell-site planning. Small-scale multipath fading is more relevant to the design of reliable and efficient communication systems – the focus of this book. We start with the physical modeling of the wireless channel in terms of elec- tromagnetic waves. We then derive an input/output linear time-varying model for the channel, and define some important physical parameters. Finally, we introduce a few statistical models of the channel variation over time and over frequency. 2.1 Physical modeling for wireless channels Wireless channels operate through electromagnetic radiation from the trans- mitter to the receiver. -

7.3.7 Video Cassette Recorders (VCR) 7.3.8 Video Disk Recorders

/7 7.3.5 Fiber-Optic Cables (FO) 7.3.6 Telephone Company Unes (TELCO) 7.3.7 Video Cassette Recorders (VCR) 7.3.8 Video Disk Recorders 7.4 Transmission Security 8. Consumer Equipment Issues 8.1 Complexity of Receivers 8.2 Receiver Input/Output Characteristics 8.2.1 RF Interface 8.2.2 Baseband Video Interface 8.2.3 Baseband Audio Interface 8.2.4 Interfacing with Ancillary Signals 8.2.5 Receiver Antenna Systems Requirements 8.3 Compatibility with Existing NTSC Consumer Equipment 8.3.1 RF Compatibility 8.3.2 Baseband Video Compatibility 8.3.3 Baseband Audio Compatibility 8.3.4 IDTV Receiver Compatibility 8.4 Allows Multi-Standard Display Devices 9. Other Considerations 9.1 Practicality of Near-Term Technological Implementation 9.2 Long-Term Viability/Rate of Obsolescence 9.3 Upgradability/Extendability 9.4 Studio/Plant Compatibility Section B: EXPLANATORY NOTES OF ATTRIBUTES/SYSTEMS MATRIX Items on the Attributes/System Matrix for which no explanatory note is provided were deemed to be self-explanatory. I. General Description (Proponent) section I shall be used by a system proponent to define the features of the system being proposed. The features shall be defined and organized under the headings ot the following subsections 1 through 4. section I. General Description (Proponent) shall consist of a description of the proponent system in narrative form, which covers all of the features and characteris tics of the system which the proponent wishe. to be included in the public record, and which will be used by various groups to analyze and understand the system proposed, and to compare with other propo.ed systems. -

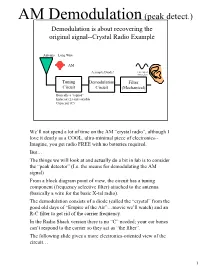

AM Demodulation(Peak Detect.)

AM Demodulation (peak detect.) Demodulation is about recovering the original signal--Crystal Radio Example Antenna = Long WireFM AM A simple Diode! (envelop of AM Signal) Tuning Demodulation Filter Circuit Circuit (Mechanical) Basically a “tapped” Inductor (L) and variable Capacitor (C) We’ll not spend a lot of time on the AM “crystal radio”, although I love it dearly as a COOL, ultra-minimal piece of electronics-- Imagine, you get radio FREE with no batteries required. But… The things we will look at and actually do a bit in lab is to consider the “peak detector” (I.e. the means for demodulating the AM signal) From a block diagram point of view, the circuit has a tuning component (frequency selective filter) attached to the antenna (basically a wire for the basic X-tal radio). The demodulation consists of a diode (called the “crystal” from the good old days of “Empire of the Air”…movie we’ll watch) and an R-C filter to get rid of the carrier frequency. In the Radio Shack version there is no “C” needed; your ear bones can’t respond to the carrier so they act as “the filter”. The following slide gives a more electronics-oriented view of the circuit… 1 Signal Flow in Crystal Radio-- +V Circuit Level Issues Wire=Antenna -V time Filter: BW •fo set by LC •BW set by RLC fo music “tuning” ground=0V time “KX” “KY” “KZ” frequency +V (only) So, here’s the incoming (modulated) signal and the parallel L-C (so-called “tank” circuit) that is hopefully selective enough (having a high enough “Q”--a term that you’ll soon come to know and love) that “tunes” the radio to the desired frequency. -

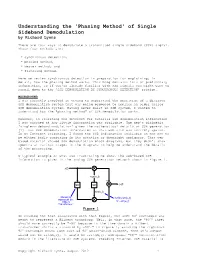

Of Single Sideband Demodulation by Richard Lyons

Understanding the 'Phasing Method' of Single Sideband Demodulation by Richard Lyons There are four ways to demodulate a transmitted single sideband (SSB) signal. Those four methods are: • synchronous detection, • phasing method, • Weaver method, and • filtering method. Here we review synchronous detection in preparation for explaining, in detail, how the phasing method works. This blog contains lots of preliminary information, so if you're already familiar with SSB signals you might want to scroll down to the 'SSB DEMODULATION BY SYNCHRONOUS DETECTION' section. BACKGROUND I was recently involved in trying to understand the operation of a discrete SSB demodulation system that was being proposed to replace an older analog SSB demodulation system. Having never built an SSB system, I wanted to understand how the "phasing method" of SSB demodulation works. However, in searching the Internet for tutorial SSB demodulation information I was shocked at how little information was available. The web's wikipedia 'single-sideband modulation' gives the mathematical details of SSB generation [1]. But SSB demodulation information at that web site was terribly sparse. In my Internet searching, I found the SSB information available on the net to be either badly confusing in its notation or downright ambiguous. That web- based material showed SSB demodulation block diagrams, but they didn't show spectra at various stages in the diagrams to help me understand the details of the processing. A typical example of what was frustrating me about the web-based SSB information is given in the analog SSB generation network shown in Figure 1. x(t) cos(ωct) + 90o 90o y(t) – sin(ωct) Meant to Is this sin(ω t) represent the c Hilbert or –sin(ωct) Transformer. -

Baseband Harmonic Distortions in Single Sideband Transmitter and Receiver System

Baseband Harmonic Distortions in Single Sideband Transmitter and Receiver System Kang Hsia Abstract: Telecommunications industry has widely adopted single sideband (SSB or complex quadrature) transmitter and receiver system, and one popular implementation for SSB system is to achieve image rejection through quadrature component image cancellation. Typically, during the SSB system characterization, the baseband fundamental tone and also the harmonic distortion products are important parameters besides image and LO feedthrough leakage. To ensure accurate characterization, the actual frequency locations of the harmonic distortion products are critical. While system designers may be tempted to assume that the harmonic distortion products are simply up-converted in the same fashion as the baseband fundamental frequency component, the actual distortion products may have surprising results and show up on the different side of spectrum. This paper discusses the theory of SSB system and the actual location of the baseband harmonic distortion products. Introduction Communications engineers have utilized SSB transmitter and receiver system because it offers better bandwidth utilization than double sideband (DSB) transmitter system. The primary cause of bandwidth overhead for the double sideband system is due to the image component during the mixing process. Given data transmission bandwidth of B, the former requires minimum bandwidth of B whereas the latter requires minimum bandwidth of 2B. While the filtering of the image component is one type of SSB implementation, another type of SSB system is to create a quadrature component of the signal and ideally cancels out the image through phase cancellation. M(t) M(t) COS(2πFct) Baseband Message Signal (BB) Modulated Signal (RF) COS(2πFct) Local Oscillator (LO) Signal Figure 1.