Energy-Detecting Receivers for Wake-Up Radio Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1 Experiment-8

Chapter 1 Experiment-8 1.1 Single Sideband Suppressed Carrier Mod- ulation 1.1.1 Objective This experiment deals with the basic of Single Side Band Suppressed Carrier (SSB SC) modulation, and demodulation techniques for analog commu- nication.− The student will learn the basic concepts of SSB modulation and using the theoretical knowledge of courses. Upon completion of the experi- ment, the student will: *UnderstandSSB modulation and the difference between SSB and DSB modulation * Learn how to construct SSB modulators * Learn how to construct SSB demodulators * Examine the I Q modulator as SSB modulator. * Possess the necessary tools to evaluate and compare the SSB SC modulation to DSB SC and DSB_TC performance of systems. − − 1.1.2 Prelab Exercise 1.Using Matlab or equivalent mathematics software, show graphically the frequency domain of SSB SC modulated signal (see equation-2) . Which of the sign is given for USB− and which for LSB. 1 2 CHAPTER 1. EXPERIMENT-8 2. Draw a block diagram and explain two method to generate SSB SC signal. − 3. Draw a block diagram and explain two method to demodulate SSB SC signal. − 4. According to the shape of the low pass filter (see appendix-1), choose a carrier frequency and modulation frequency in order to implement LSB SSB modulator, with minimun of 30 dB attenuation of the USB component. 1.1.3 Background Theory SSB Modulation DEFINITION: An upper single sideband (USSB) signal has a zero-valued spectrum for f <fcwhere fc, is the carrier frequency. A lower single| | sideband (LSSB) signal has a zero-valued spectrum for f >fc where fc, is the carrier frequency. -

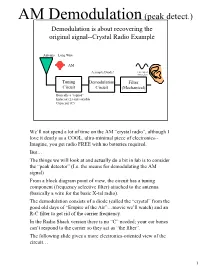

AM Demodulation(Peak Detect.)

AM Demodulation (peak detect.) Demodulation is about recovering the original signal--Crystal Radio Example Antenna = Long WireFM AM A simple Diode! (envelop of AM Signal) Tuning Demodulation Filter Circuit Circuit (Mechanical) Basically a “tapped” Inductor (L) and variable Capacitor (C) We’ll not spend a lot of time on the AM “crystal radio”, although I love it dearly as a COOL, ultra-minimal piece of electronics-- Imagine, you get radio FREE with no batteries required. But… The things we will look at and actually do a bit in lab is to consider the “peak detector” (I.e. the means for demodulating the AM signal) From a block diagram point of view, the circuit has a tuning component (frequency selective filter) attached to the antenna (basically a wire for the basic X-tal radio). The demodulation consists of a diode (called the “crystal” from the good old days of “Empire of the Air”…movie we’ll watch) and an R-C filter to get rid of the carrier frequency. In the Radio Shack version there is no “C” needed; your ear bones can’t respond to the carrier so they act as “the filter”. The following slide gives a more electronics-oriented view of the circuit… 1 Signal Flow in Crystal Radio-- +V Circuit Level Issues Wire=Antenna -V time Filter: BW •fo set by LC •BW set by RLC fo music “tuning” ground=0V time “KX” “KY” “KZ” frequency +V (only) So, here’s the incoming (modulated) signal and the parallel L-C (so-called “tank” circuit) that is hopefully selective enough (having a high enough “Q”--a term that you’ll soon come to know and love) that “tunes” the radio to the desired frequency. -

EE426/506 Class Notes 4/23/2015 John Stensby

EE426/506 Class Notes 4/23/2015 John Stensby Chapter 2: Basic Modulation Techniques In most communication systems, the modulated signal has the form xcc (t) A(t)cos[ t (t)], (2-1) where c is known as the carrier frequency, A(t) is the envelope and (t) is the phase. Amplitude A(t) and phase (t) may depend on message m(t). When A(t) depends linearly on the message, and is a constant independent of m, we have linear modulation. When (t) depends on m(t), we have nonlinear modulation. Linear Modulation Double Sideband (DSB) is the first form of linear modulation we will consider. The general form of a DSB signal is x(t)Am(t)cos[tDSB cc0 ], (2-2) where Ac and are constants. For convenience, we will assume that = 0. Figures 2-1a through 2-1c depict a block diagram of a DSB modulator, a sinusoidal message m and the DSB time domain wave form xDSB(t), respectively. Note that every sign change in m(t) results in a ° 180 phase shift in the transmitted signal xDSB(t). DSB is very popular when used to transmit digital data. In this application, m(t) is a digital waveform that switches between +1 and -1 volts. Hence, m(t) switches the phase of the transmitted carrier by radians. For this reason, for a ±1 binary message, the modulation is called phase-shift keying. The Fourier transform of xDSB is A X(j)x(t)M(jj)M(jj)F c , (2-3) DSB DSB2 c c Latest Updates at http://www.ece.uah.edu/courses/ee426/ 2-1 EE426/506 Class Notes 4/23/2015 John Stensby m(t) a) xDSB(t) = Acm(t)cosct Accosct m(t) b) t (t) DSB x c) t Figure 2-1: a) Block diagram of a DSB modulator. -

Signi\L PURITY CONS IDERI\TIONS for FREQUEN<:Y Sn1 Tiles I ZED Llel\DEND EQU I Pr1ent David L. Kel:Na General Instrument

SIGNi\L PURITY CONS IDERI\TIONS FOR FREQUEN<:Y Sn1 TilES I ZED llEl\DEND EQU I Pr1ENT David L. Kel:na General Instrument, Jerrold Division ABSTRACT BASIC OVERVIEW OF THE PLL As cabl~ television system band Before we evoluate the system for wirlths increase and frequency plans pro its noise performance, let us first re liferate, more manufacturers are turning view the b~sic operation of a chase to synth~sized frequency agile head~nd locked loop. A simple phase-locked loop channel converters. Uith this new ap consists of a voltage controlled oscil proach using phased lo~ked loops and dual lator, or VCO, a digital divider, a chase conversion come spurious signals and detector, a reference frequency sour~e, nois~ sources not encountered before in and an integrator or loop filter. Figure crystal controlled channel converters. 1 represents such a system. Important characteristics of these These system components function ~s headend converters including phas~ noise, a s~rvo loop sue~ that when the·vco is spurious sign3ls generated by the compar phase-locked to the reference, the output ison frequ~ncy, and residual frequency frequency and phase of the digital divi a~d phase modulation, are evaluated for der is equal to the frequency and phase their subjective impact on the output of the referenc~. This makes the average signal to the cable. D3ta is presented output of the phase detector zero and, which shows the correlation between sub therefore, the output of the loop filter jective picture degradation and measured remains unchanged. Should a disturbance headend synthesizer noise contribution. -

Amplitude Modulation “AM” with Envelope Detector

Amplitude Modulation “AM” with Envelope Detector Large S/N limit m1< s(t) ≅ sin ωm t ≤ 1 Recei ved = y(t) = Ac [1 + m s( t)] cos ωc t + nc (t)cos ωc t + ns (t)s in ωct j ωct = Re {Y (t)e } slowly varying y, low-pass filtered (envelope) “overmodulation” = distortion (“undermodulation = wasted power) Lec 16b.6-1 2/2/01 T1 Amplitude Modulation “AM” with Envelope Detector Recei ved = y(t) = Ac [1 + m s( t)] cos ωc t + nc (t)cos ωc t + ns (t)s in ωct j ωct = Re {Y (t)e } slowly varying Im {Y (t)} Y(f ) 2W Y(t) ns(t) n(t) R e {Y(t) } f 0 0 fc A [1 + m s(t)] nc(t) N = kT c o 2 Lec 16b.6-2 2/2/01 T2 Amplitude Modulation “AM” with Envelope Detector Im {Y (t)} Y(f ) 2W Y(t) ns(t) n(t) R e {Y(t) } f 0 0 fc A [1 + m s(t)] nc(t) N = kT c o 2 Y(t) ≅ A [1 + m s(t)] + n (t) N c c envelope = detected signal + noise 2 2 2 2 2 Note: 4WNo = nc cos ωc t + ns sin ωc t = nc 222 Sout 222 2 Ac ms (t) ≅ Ac m s (t) nc (t) = Nout 4WNo Lec 16b.6-3 2/2/01 T3 Amplitude Modulation “AM” with Envelope Detector 222 Sout 222 2 Ac ms (t) ≅ Ac m s (t) nc (t) = Nout 4WNo 2 2 A 2 (1 + m s(t)) Sin ( c ) 2 ≅ where Sin = y signal(t) Nin 4WNo 22 ∆ SNi i 1m+ s (t) 11+ 2 Noi se figure FAM = = ≥ = 3 2 ⇒ FAM ≥ 3 2 SNo o 2m 22s 1 provided that Ac >> nc (large S/N limit) Lec 16b.6-4 2/2/01 T4 AM Performance (small S/N limit) Im {Y } φ (t) n A1c [ + m s(t)] n(t) ≅ Ac [1 + m s( t)] cos φn (t) φn (t) R e {}Y Y(t) ≅ n(t) + A cos φ (t) + A m s( t)cos φ (t) c n c n multiplicative noise! Want Sin Nin ≥ 10 for fully i ntel ligibl e AM ⇒ "AM threshold" ( i.e. -

ES442 Lab 6 Frequency Modulation and Demodulation

ES442 Lab#6 ES442 Lab 6 Frequency Modulation and Demodulation Objective 1. Build simple FM demodulator by using frequency discriminator 2. Build simple envelope detector for FM demodulation. 3. Using MATLAB m-file and simulink to implement FM modulation and demodulation. Part List 1uF capacitor (2); 10.0Kohm resistor, 1.0Kohm resistor, Power supply with +/-5V, Scope and frequency analyzer, FM signal Generator. Estimated Time About 90 minutes. Introduction Frequency modulation is a form of modulation, which represents information as variations in the instantaneous frequency of a carrier wave. In analog applications, the carrier frequency is varied in direct proportion to changes in the amplitude of an input signal. This is shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1, Frequency modulation. The FM-modulated signal has its instantaneous frequency that varies linearly with the amplitude of the message signal. Now we can get the FM-modulation by the following: where Kƒ is the sensitivity factor, and represents the frequency deviation rate as a result of message amplitude change. The instantaneous frequency is: Ver 2. 1 ES442 Lab#6 The maximum deviation of Fc (which represents the max. shift away from Fc in one direction) is: Note that The FM-modulation is implemented by controlling the instantaneous frequency of a voltage-controlled oscillator(VCO). The amplitude of the input signal controls the oscillation frequency of the VCO output signal. In the FM demodulation what we need to recover is the variation of the instantaneous frequency of the carrier, either above or below the center frequency. The detecting device must be constructed so that its output amplitude will vary linearly according to the instantaneous freq. -

Low-Power RFED Wake-Up Receiver Design for Low-Cost Wireless Sensor Network Applications

sensors Article Low-Power RFED Wake-Up Receiver Design for Low-Cost Wireless Sensor Network Applications David Galante-Sempere , Dailos Ramos-Valido, Sunil Lalchand Khemchandani and Javier del Pino * Institute for Applied Microelectronics (IUMA), University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (ULPGC), 35017 Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain; [email protected] (D.G.-S.); [email protected] (D.R.-V.); [email protected] (S.L.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 September 2020; Accepted: 6 November 2020; Published: 10 November 2020 Abstract: The development of wake-up receivers (WuR) has recently received a lot of interest from both academia and industry researchers, primarily because of their major impact on the improvement of the performance of wireless sensor networks (WSNs). In this paper, we present the development of three different radiofrequency envelope detection (RFED) based WuRs operating at the 868 MHz industrial, scientific and medical (ISM) band. These circuits can find application in densely populated WSNs, which are fundamental components of Internet-of-Things (IoT) or Internet-of-Everything (IoE) applications. The aim of this work is to provide circuits with high integrability and a low cost-per-node, so as to facilitate the implementation of sensor nodes in low-cost IoT applications. In order to demonstrate the feasibility of implementing a WuR with commercially available off-chip components, the design of an RFED WuR in a PCB mount is presented. The circuit is validated in a real scenario by testing the WuR in a system with a pattern recognizer (AS3933), an MCU (MSP430G2553 from TI), a transceiver (CC1101 from TI) and a T/R switch (ADG918). -

Easy Fourier Analysis

Easy Fourier Analysis http://www.complextoreal.com/base.htm SpectrumDCInformationSignal term at 2w on csignal the positivenegative x-axis Half is up This half is shifted. down shifted. Charan Langton, The Carrier Editor fm = -1 fm = -9, fc-9,-9 -8, = -8, -8-7 -7 -9, -8, -7 SIGNAL PROCESSING & SIMULATION NEWSLETTER Baseband, Passband Signals and Amplitude Modulation The most salient feature of information signals is that they are generally low frequency. Sometimes this is due to the nature of data itself such as human voice which has frequency components from 300 Hz to app. 20 KHz. Other times, such as data from a digital circuit inside a computer, the low rates are due to hardware limitations. Due to their low frequency content, the information signals have a spectrum such as that in the figure below. There are a lot of low frequency components and the one-sided spectrum is located near the zero frequency. Figure 1 - The spectrum of an information signal is usually limited to low frequencies The hypothetical signal above has four sinusoids, all of which are fairly close to zero. The frequency range of this signal extends from zero to a maximum frequency of fm. We say that this signal has a bandwidth of fm. In the time domain this 4 component signal may looks as shown in Figure 2. Figure 2 - Time domain low frequency information signal 1 of 18 1/25/2008 3:42 AM Easy Fourier Analysis http://www.complextoreal.com/base.htm Now let’s modulate this signal, which means we are going to transfer it to a higher (usually much higher) frequency. -

EE133 Winter 2004 1

Prelab 1 - AM Modulation - Prof. Dutton - EE133 Winter 2004 1 EE133 - Prelab 1 Amplitude Modulation and Demodulation 1 Introduction This week we will be taking a look at the amplitude modulation (AM) scheme. In this process, the amplitude of the carrier signal is varied so that it is proportional to the instantaneous amplitude of the modulating signal. With the invention of oscillators, this scheme quickly supplanted the first spark-gap transmitters. They did so because AM supported the easy transmission of voice while allowing more people to transmit without interfering with each other. For an oscillating electrical signal to be transmitted through the air, it must first be converted into elec- tromagnetic radiation. To maximize efficiency of transmission, the physical dimensions of the transmitting and receiving antennas must be on the same order of magnitude as the wavelength of the transmitted signal (often a quarter wavelength). For audio signals, whose frequencies range from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, this corre- sponds to wavelengths from 15 to 15000 km. As you can probably guess, an antenna of this length would be absurd for general applications. AM solves this problem by using a ’slow’ moving audio signal to modulate a fast moving, radio signal. The fast signal is called the carrier signal, and the audio frequency signal is typically called the modulating signal. Typical carrier frequencies range from 30 kHz to upwards of 30 GHz. By using a carrier frequency, users can ’tune’ into a particular transmitter. With the old spark-gap transmit- ters, every user heard all transmitters that were within range. -

Easy Fourier Analysis

SpectrumDCInformationSignal term at 2won signal cthe positivenegative Half is up This half is .3 x-axis .5 shifted. down shifted. Charan Langton, TheEditor Carrier fm = -1 fm = 1 -9 9 -9, fc-9, -8, = -8, -8-7 -7 -7 7, fc7 7,8,= 8 8,9 9 -9, -8, -7 7, 8, 9 SIGNAL PROCESSING & SIMULATION NEWSLETTER Baseband, Passband Signals and Amplitude Modulation The most salient feature of information signals is that they are generally low frequency. Sometimes this is due to the nature of data itself such as human voice which has frequency components from 300 Hz to app. 20 KHz. Other times, such as data from a digital circuit inside a computer, the low rates are due to hardware limitations. Due to their low frequency content, the information signals have a spectrum such as that in the figure below. There are a lot of low frequency components and the one-sided spectrum is located near the zero frequency. .......... Figure 1 - The spectrum of an information signal is usually limited to low frequencies The hypothetical signal above has four sinusoids, all of which are fairly close to zero. The frequency range of this signal extends from zero to a maximum frequency of fm. We say that this signal has a bandwidth of fm. In the time domain this 4 component signal may looks as shown in Figure 2. Figure 2 - Time domain low frequency information signal Now let’s modulate this signal, which means we are going to transfer it to a higher (usually much higher) frequency. Just as information signals are characterized by their low frequency, the transmission medium, or carriers are characterized by their high frequency. -

Detection and Classification of Frequency-Hopped Spread Spectrum Signals James Eric Dunn Iowa State University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Repository @ Iowa State University Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1991 Detection and classification of frequency-hopped spread spectrum signals James Eric Dunn Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Electrical and Electronics Commons Recommended Citation Dunn, James Eric, "Detection and classification of frequency-hopped spread spectrum signals " (1991). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10027. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10027 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Product Demodulation - Synchronous & Asynchronous

PRODUCT DEMODULATION - SYNCHRONOUS & ASYNCHRONOUS INTRODUCTION...............................................................................98 frequency translation..................................................................98 the process................................................................................................98 interpretation ............................................................................................99 the demodulator .......................................................................100 ω ω synchronous operation: 0 = 1 ...........................................................100 carrier acquisition...................................................................................101 ω ω asynchronous operation: 0 =/= 1 .....................................................101 signal identification .................................................................101 demodulation of DSBSC........................................................................102 demodulation of SSB .............................................................................102 demodulation of ISB ..............................................................................103 EXPERIMENT .................................................................................103 synchronous demodulation ......................................................103 asynchronous demodulation ....................................................104 SSB reception.........................................................................................105