EE133 Winter 2004 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1 Experiment-8

Chapter 1 Experiment-8 1.1 Single Sideband Suppressed Carrier Mod- ulation 1.1.1 Objective This experiment deals with the basic of Single Side Band Suppressed Carrier (SSB SC) modulation, and demodulation techniques for analog commu- nication.− The student will learn the basic concepts of SSB modulation and using the theoretical knowledge of courses. Upon completion of the experi- ment, the student will: *UnderstandSSB modulation and the difference between SSB and DSB modulation * Learn how to construct SSB modulators * Learn how to construct SSB demodulators * Examine the I Q modulator as SSB modulator. * Possess the necessary tools to evaluate and compare the SSB SC modulation to DSB SC and DSB_TC performance of systems. − − 1.1.2 Prelab Exercise 1.Using Matlab or equivalent mathematics software, show graphically the frequency domain of SSB SC modulated signal (see equation-2) . Which of the sign is given for USB− and which for LSB. 1 2 CHAPTER 1. EXPERIMENT-8 2. Draw a block diagram and explain two method to generate SSB SC signal. − 3. Draw a block diagram and explain two method to demodulate SSB SC signal. − 4. According to the shape of the low pass filter (see appendix-1), choose a carrier frequency and modulation frequency in order to implement LSB SSB modulator, with minimun of 30 dB attenuation of the USB component. 1.1.3 Background Theory SSB Modulation DEFINITION: An upper single sideband (USSB) signal has a zero-valued spectrum for f <fcwhere fc, is the carrier frequency. A lower single| | sideband (LSSB) signal has a zero-valued spectrum for f >fc where fc, is the carrier frequency. -

Lecture 25 Demodulation and the Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-10

EE447 Lecture 6 Lecture 25 Demodulation and the Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-10 HW7;5-4,5-7,5-13a-d,5-23,5-31 Due next Monday, 29th 1 Figure 4–29 Superheterodyne receiver. m(t) 2 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. 0-13-142492-0 1 EE447 Lecture 6 Synchronous Demodulation s(t) LPF m(t) 2Cos(2πfct) •Only method for DSB-SC, USB-SC, LSB-SC •AM with carrier •Envelope Detection – Input SNR >~10 dB required •Synchronous Detection – (no threshold effect) •Note the 2 on the LO normalizes the output amplitude 3 Figure 4–24 PLL used for coherent detection of AM. 4 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. 0-13-142492-0 2 EE447 Lecture 6 Envelope Detector C • Ac • (1+ a • m(t)) Where C is a constant C • Ac • a • m(t)) 5 Envelope Detector Distortion Hi Frequency m(t) Slope overload IF Frequency Present in Output signal 6 3 EE447 Lecture 6 Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-09 7 8 4 EE447 Lecture 6 9 Super-Heterodyne AM Receiver 10 5 EE447 Lecture 6 Super-Heterodyne AM Receiver 11 RF Filter • Provides Image Rejection fimage=fLO+fif • Reduces amplitude of interfering signals far from the carrier frequency • Reduces the amount of LO signal that radiates from the Antenna stop 2/22 12 6 EE447 Lecture 6 Figure 4–30 Spectra of signals and transfer function of an RF amplifier in a superheterodyne receiver. 13 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. -

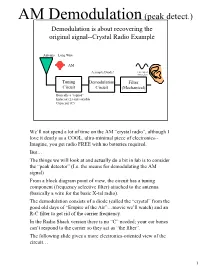

AM Demodulation(Peak Detect.)

AM Demodulation (peak detect.) Demodulation is about recovering the original signal--Crystal Radio Example Antenna = Long WireFM AM A simple Diode! (envelop of AM Signal) Tuning Demodulation Filter Circuit Circuit (Mechanical) Basically a “tapped” Inductor (L) and variable Capacitor (C) We’ll not spend a lot of time on the AM “crystal radio”, although I love it dearly as a COOL, ultra-minimal piece of electronics-- Imagine, you get radio FREE with no batteries required. But… The things we will look at and actually do a bit in lab is to consider the “peak detector” (I.e. the means for demodulating the AM signal) From a block diagram point of view, the circuit has a tuning component (frequency selective filter) attached to the antenna (basically a wire for the basic X-tal radio). The demodulation consists of a diode (called the “crystal” from the good old days of “Empire of the Air”…movie we’ll watch) and an R-C filter to get rid of the carrier frequency. In the Radio Shack version there is no “C” needed; your ear bones can’t respond to the carrier so they act as “the filter”. The following slide gives a more electronics-oriented view of the circuit… 1 Signal Flow in Crystal Radio-- +V Circuit Level Issues Wire=Antenna -V time Filter: BW •fo set by LC •BW set by RLC fo music “tuning” ground=0V time “KX” “KY” “KZ” frequency +V (only) So, here’s the incoming (modulated) signal and the parallel L-C (so-called “tank” circuit) that is hopefully selective enough (having a high enough “Q”--a term that you’ll soon come to know and love) that “tunes” the radio to the desired frequency. -

Additive Synthesis, Amplitude Modulation and Frequency Modulation

Additive Synthesis, Amplitude Modulation and Frequency Modulation Prof Eduardo R Miranda Varèse-Gastprofessor [email protected] Electronic Music Studio TU Berlin Institute of Communications Research http://www.kgw.tu-berlin.de/ Topics: Additive Synthesis Amplitude Modulation (and Ring Modulation) Frequency Modulation Additive Synthesis • The technique assumes that any periodic waveform can be modelled as a sum sinusoids at various amplitude envelopes and time-varying frequencies. • Works by summing up individually generated sinusoids in order to form a specific sound. Additive Synthesis eg21 Additive Synthesis eg24 • A very powerful and flexible technique. • But it is difficult to control manually and is computationally expensive. • Musical timbres: composed of dozens of time-varying partials. • It requires dozens of oscillators, noise generators and envelopes to obtain convincing simulations of acoustic sounds. • The specification and control of the parameter values for these components are difficult and time consuming. • Alternative approach: tools to obtain the synthesis parameters automatically from the analysis of the spectrum of sampled sounds. Amplitude Modulation • Modulation occurs when some aspect of an audio signal (carrier) varies according to the behaviour of another signal (modulator). • AM = when a modulator drives the amplitude of a carrier. • Simple AM: uses only 2 sinewave oscillators. eg23 • Complex AM: may involve more than 2 signals; or signals other than sinewaves may be employed as carriers and/or modulators. • Two types of AM: a) Classic AM b) Ring Modulation Classic AM • The output from the modulator is added to an offset amplitude value. • If there is no modulation, then the amplitude of the carrier will be equal to the offset. -

Of Single Sideband Demodulation by Richard Lyons

Understanding the 'Phasing Method' of Single Sideband Demodulation by Richard Lyons There are four ways to demodulate a transmitted single sideband (SSB) signal. Those four methods are: • synchronous detection, • phasing method, • Weaver method, and • filtering method. Here we review synchronous detection in preparation for explaining, in detail, how the phasing method works. This blog contains lots of preliminary information, so if you're already familiar with SSB signals you might want to scroll down to the 'SSB DEMODULATION BY SYNCHRONOUS DETECTION' section. BACKGROUND I was recently involved in trying to understand the operation of a discrete SSB demodulation system that was being proposed to replace an older analog SSB demodulation system. Having never built an SSB system, I wanted to understand how the "phasing method" of SSB demodulation works. However, in searching the Internet for tutorial SSB demodulation information I was shocked at how little information was available. The web's wikipedia 'single-sideband modulation' gives the mathematical details of SSB generation [1]. But SSB demodulation information at that web site was terribly sparse. In my Internet searching, I found the SSB information available on the net to be either badly confusing in its notation or downright ambiguous. That web- based material showed SSB demodulation block diagrams, but they didn't show spectra at various stages in the diagrams to help me understand the details of the processing. A typical example of what was frustrating me about the web-based SSB information is given in the analog SSB generation network shown in Figure 1. x(t) cos(ωct) + 90o 90o y(t) – sin(ωct) Meant to Is this sin(ω t) represent the c Hilbert or –sin(ωct) Transformer. -

Energy-Detecting Receivers for Wake-Up Radio Applications

Energy-Detecting Receivers for Wake-Up Radio Applications Vivek Mangal Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2019 Vivek Mangal All Rights Reserved Abstract Energy-Detecting Receivers for Wake-Up Radio Applications Vivek Mangal In an energy-limited wireless sensor node application, the main transceiver for communication has to operate in deep sleep mode when inactive to prolong the node battery lifetime. Wake-up is among the most efficient scheme which uses an always ON low-power receiver called the wake-up receiver to turn ON the main receiver when required. Energy-detecting receivers are the best fit for such low power operations. This thesis discusses the energy-detecting receiver design; challenges; techniques to enhance sensitivity, selectivity; and multi-access operation. Self-mixers instead of the conventional envelope detectors are proposed and proved to be op- timal for signal detection in these energy-detection receivers. A fully integrated wake-up receiver using the self-mixer in 65 nm LP CMOS technology has a sensitivity of −79.1 dBm at 434 MHz. With scaling, time-encoded signal processing leveraging switching speeds have become attractive. Baseband circuits employing time-encoded matched filter and comparator with DC offset compen- sation loop are used to operate the receiver at 420 pW power. Another prototype at 1.016 GHz is sensitive to −74 dBm signal while consuming 470 pW. The proposed architecture has 8 dB better sensitivity at 10 dB lower power consumption across receiver prototypes. -

An Analysis of a Quadrature Double-Sideband/Frequency Modulated Communication System

Scholars' Mine Masters Theses Student Theses and Dissertations 1970 An analysis of a quadrature double-sideband/frequency modulated communication system Denny Ray Townson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses Part of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons Department: Recommended Citation Townson, Denny Ray, "An analysis of a quadrature double-sideband/frequency modulated communication system" (1970). Masters Theses. 7225. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses/7225 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF A QUADRATURE DOUBLE- SIDEBAND/FREQUENCY MODULATED COMMUNICATION SYSTEM BY DENNY RAY TOWNSON, 1947- A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI - ROLLA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 1970 ii ABSTRACT A QDSB/FM communication system is analyzed with emphasis placed on the QDSB demodulation process and the AGC action in the FM transmitter. The effect of noise in both the pilot and message signals is investigated. The detection gain and mean square error is calculated for the QDSB baseband demodulation process. The mean square error is also evaluated for the QDSB/FM system. The AGC circuit is simulated on a digital computer. Errors introduced into the AGC system are analyzed with emphasis placed on nonlinear gain functions for the voltage con trolled amplifier. -

E2L005 ROTCH a Day in the Life of the RF Spectrum

A Day in the Life of the RF Spectrum by James E. Cooley B.S., Computer Engineering Northwestern University (1999) Submitted to the Program of Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MEDIA ARTS AND SCIENCES at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 2005 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2005. All rights reserved. Signature of Author: Program in Media Arts and Sciences August 5, 2005 Certified by: Andrew B. Lippman Senior Research Scientist of Media Arts and Sciences Program in Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Andrew B. Lippman Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies Program in Media Arts and Sciences tMASSACHUSETT NSE IT 'F TECHNOLOG Y E2L005 ROTCH A Day in the Life of the RF Spectrum by James E. Cooley Submitted to the Program of Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, September 2005 in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences Abstract There is a misguided perception that RF spectrum space is fully allocated and fully used though even a superficial study of actual spectrum usage by measuring local RF energy shows it largely empty of radiation. Traditional regulation uses a fence-off policy, in which competing uses are isolated by frequency and/or geography. We seek to modernize this strategy. Given advances in radio technology that can lead to fully cooperative broadcast, relay, and reception designs, we begin by studying the existing radio environment in a qualitative manner. -

Amplitude Modulation(AM)

Introduction to Modulation: Amplitude Modulation(AM) Sharlene Katz James Flynn Overview Modulation Overview Basics of Amplitude Modulation (AM) AM Demonstration GRC Exercise 2 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Why do we need Modulation/Demodulation? Example: Radio transmission Voice Microphone Transmitter Electric signal, Antenna: 20 Hz – 20 Size requirement KHz > 1/10 wavelength c 3×108 Antenna too large! 5 Use modulation to At 3 KHz: λ = = 3 =10 =100km f 3×10 transfer ⇒ .1λ =10km information to a higher frequency 3 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Why do we need Modulation/Demodulation? (cont’d) Frequency Assignment Reduction of noise/interference Multiplexing Bandwidth limitations of equipment Frequency characteristics of antennas Atmospheric/cable properties 4 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Basic Concept of Modulation The information source Typically a low frequency signal Referred to as the “baseband signal” X(f) x(t) t f Carrier A higher frequency sinusoid baseband Modulated Modulator Example: cos(2π10000t) carrier signal Modulated Signal Some parameter of the carrier (amplitude, frequency, phase) is varied in accordance with the baseband signal 5 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Types of Modulation Analog Modulation Amplitude Modulation, AM Frequency Modulation, FM Double and Single Sideband, DSB and SSB Digital Modulation Phase Shift Keying: BPSK, QPSK, MSK Frequency Shift Keying, FSK Quadrature Amplitude Modulation, QAM 6 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Amplitude Modulation (AM) Block Diagram x(t) m x + xAM(t)=Ac [1+mx(t)]cos wct Ac cos wct Time Domain Signal information -

![Arxiv:1306.0942V2 [Cond-Mat.Mtrl-Sci] 7 Jun 2013](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1341/arxiv-1306-0942v2-cond-mat-mtrl-sci-7-jun-2013-1331341.webp)

Arxiv:1306.0942V2 [Cond-Mat.Mtrl-Sci] 7 Jun 2013

Bipolar electrical switching in metal-metal contacts Gaurav Gandhi1, a) and Varun Aggarwal1, b) mLabs, New Delhi, India Electrical switching has been observed in carefully designed metal-insulator-metal devices built at small geometries. These devices are also commonly known as mem- ristors and consist of specific materials such as transition metal oxides, chalcogenides, perovskites, oxides with valence defects, or a combination of an inert and an electro- chemically active electrode. No simple physical device has been reported to exhibit electrical switching. We have discovered that a simple point-contact or a granu- lar arrangement formed of metal pieces exhibits bipolar switching. These devices, referred to as coherers, were considered as one-way electrical fuses. We have identi- fied the state variable governing the resistance state and can program the device to switch between multiple stable resistance states. Our observations render previously postulated thermal mechanisms for their resistance-change as inadequate. These de- vices constitute the missing canonical physical implementations for memristor, often referred as the fourth passive element. Apart from the theoretical advance in un- derstanding metallic contacts, the current discovery provides a simple memristor to physicists and engineers for widespread experimentation, hitherto impossible. arXiv:1306.0942v2 [cond-mat.mtrl-sci] 7 Jun 2013 a)Electronic mail: [email protected] b)Electronic mail: [email protected] 1 I. INTRODUCTION Leon Chua defines a memristor as any two-terminal electronic device that is devoid of an internal power-source and is capable of switching between two resistance states upon application of an appropriate voltage or current signal that can be sensed by applying a relatively much smaller sensing signal1. -

Fm Demodulation Using a Digital Radio and Digital Signal Processing

FM DEMODULATION USING A DIGITAL RADIO AND DIGITAL SIGNAL PROCESSING By JAMES MICHAEL SHIMA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1995 Copyright 1995 by James Michael Shima To my mother, Roslyn Szego, and To the memory of my grandmother, Evelyn Richmond. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Mike Dollard and John Abaunza for their extended support of my research. Moreover, their guidance and constant tutoring were unilaterally responsible for the origin of this thesis. I am also grateful to Dr. Scott Miller, Dr. Jose Principe, and Dr. Michel Lynch for their support of my research and their help with my thesis. I appreciate their investment of time to be on my supervisory committee. Mostly, I must greatly thank and acknowledge my mother and father, Ronald and Roslyn Szego. Without their unending help in every facet of life, I would not be where I am today. I also acknowledge and greatly appreciate the financial help of my grandmother, Mae Shima. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER 1 ........................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background Overview ............................................................................................1 -

Amplitude Modulation

ENSC327 Communications Systems 3. Amplitude Modulation School of Engineering Science Simon Fraser University 1 Outline Some Required Background Overview of Modulation What is modulation? Why modulation? Overview of analog modulation History of AM & FM Radio Broadcast Linear Modulation: Amplitude modulation 2 Some Required Background Basics of sinusoidal signals: amplitude, frequency, phase. RC Circuits, Natural Response. Assume initial voltage to be ( ). Recall from ENSC-220, what is ( )? 0 Fourier Transform of cos 2 or a complex exponential. Properties of FT, e.g., shift in frequency, Parseval’s theorem. Definition of Bandwidth (BW) (see Lecture 2) 3 Overview of Modulation What is modulation? The process of varying a carrier signal in order to use that signal to convey information. Why modulation? 1. Reducing the size of the antennas: The optimal antenna size is related to wavelength: Voice signal: 3 kHz 4 Overview of Modulation Why modulation? 2. Allowing transmission of more than one signal in the same channel (multiplexing) 3. Allowing better trade-off between bandwidth and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) 5 Analog modulation The input message is continuous in time and value Continuous-wave modulation (focus of this course) A parameter of a high-freq carrier is varied in accordance with the message signal If a sinusoidal carrier is used, the modulated carrier is: Linear modulation: A(t) is linearly related to the message. AM, DSB, SSB Angle modulation: Phase modulation: Φ(t) is linearly related the message. Freq.