The Immigrant Image in the Baltimore Riots of 1812 and the Disagreement Over Nationality John K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Life in the Early Republic: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Social life in the early republic vii PREFACE peared to them, or recall the quaint figures of Mrs. Alexander Hamilton and Mrs. Madison in old age, or the younger faces of Cora Livingston, Adèle Cutts, Mrs. Gardiner G. Howland, and Madame de Potestad. To those who have aided her with personal recollections or valuable family papers and letters the author makes grateful acknowledgment, her thanks being especially due to Mrs. Samuel Phillips Lee, Mrs. Beverly Kennon, Mrs. M. E. Donelson Wilcox, Miss Virginia Mason, Mr. James Nourse and the Misses Nourse of the Highlands, to Mrs. Robert K. Stone, Miss Fanny Lee Jones, Mrs. Semple, Mrs. Julia F. Snow, Mr. J. Henley Smith, Mrs. Thompson H. Alexander, Miss Rosa Mordecai, Mrs. Harriot Stoddert Turner, Miss Caroline Miller, Mrs. T. Skipwith Coles, Dr. James Dudley Morgan, and Mr. Charles Washington Coleman. A. H. W. Philadelphia, October, 1902. ix CONTENTS Chapter Page I— A Social Evolution 13 II— A Predestined Capital 42 Social life in the early republic http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.29033 Library of Congress III— Homes and Hostelries 58 IV— County Families 78 V— Jeffersonian Simplicity 102 VI— A Queen of Hearts 131 VII— The Bladensburg Races 161 VII— Peace and Plenty 179 IX— Classics and Cotillions 208 X— A Ladies' Battle 236 XI— Through Several Administrations 267 XII— Mid-Century Gayeties 296 xi ILLUSTRATIONS Page Mrs. Richard Gittings, of Baltimore (Polly Sterett) Frontispiece From portrait by Charles Willson Peale, owned by her great-grandson, Mr. D. Sterett Gittings, of Baltimore. Mrs. Gittings eyes are dark brown, the hair dark brown, with lighter shades through it; the gown of delicate pink, the sleeves caught up with pearls, the sash of a gray shade. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

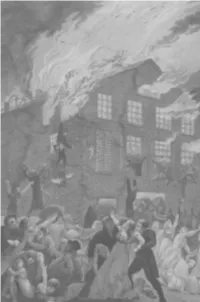

The Baltimore Riots of 1812 and the Breakdown of the Anglo-American Mob Tradition Author(S): Paul A

Peter N. Stearns The Baltimore Riots of 1812 and the Breakdown of the Anglo-American Mob Tradition Author(s): Paul A. Gilje Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Social History, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Summer, 1980), pp. 547-564 Published by: Peter N. Stearns Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3787432 . Accessed: 02/11/2011 21:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Peter N. Stearns is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Social History. http://www.jstor.org THEBALTIMORE RIOTS OF 1812AND THE BREAKDOWNOF THE ANGLO-AMERICAN MOB TRADITION The nature of rioting-what riotersdid-was undergoinga transformationin the half century after the American Revolution. A close examination of the extensive rioting in Baltimoreduring the summer of 1812 suggests what those changes were. Telescopedinto a month and a half of riotingwas a rangeof activity revealing the breakdownof the Anglo-Americanmob tradition.l This tradition allowed for a certainamount of limited populardisorder. The tumultuouscrowd was viewed as a "quasi-legitimate"or "extra-institutionals'part -

Guide to the War of 1812 Sources

Source Guide to the War of 1812 Table of Contents I. Military Journals, Letters and Personal Accounts 2 Service Records 5 Maritime 6 Histories 10 II. Civilian Personal and Family Papers 12 Political Affairs 14 Business Papers 15 Histories 16 III. Other Broadsides 17 Maps 18 Newspapers 18 Periodicals 19 Photos and Illustrations 19 Genealogy 21 Histories of the War of 1812 23 Maryland in the War of 1812 25 This document serves as a guide to the Maryland Center for History and Culture’s library items and archival collections related to the War of 1812. It includes manuscript collections (MS), vertical files (VF), published works, maps, prints, and photographs that may support research on the military, political, civilian, social, and economic dimensions of the war, including the United States’ relations with France and Great Britain in the decade preceding the conflict. The bulk of the manuscript material relates to military operations in the Chesapeake Bay region, Maryland politics, Baltimore- based privateers, and the impact of economic sanctions and the British blockade of the Bay (1813-1814) on Maryland merchants. Many manuscript collections, however, may support research on other theaters of the war and include correspondence between Marylanders and military and political leaders from other regions. Although this inventory includes the most significant manuscript collections and published works related to the War of 1812, it is not comprehensive. Library and archival staff are continually identifying relevant sources in MCHC’s holdings and acquiring new sources that will be added to this inventory. Accordingly, researchers should use this guide as a starting point in their research and a supplement to thorough searches in MCHC’s online library catalog. -

Maryland Historical Magazine Patricia Dockman Anderson, Editor Matthew Hetrick, Associate Editor Christopher T

Winter 2014 MARYLAND Ma Keeping the Faith: The Catholic Context and Content of ry la Justus Engelhardt Kühn’s Portrait of Eleanor Darnall, ca. 1710 nd Historical Magazine by Elisabeth L. Roark Hi st or James Madison, the War of 1812, and the Paradox of a ic al Republican Presidency Ma by Jeff Broadwater gazine Garitee v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore: A Gilded Age Debate on the Role and Limits of Local Government by James Risk and Kevin Attridge Research Notes & Maryland Miscellany Old Defenders: The Intermediate Men, by James H. Neill and Oleg Panczenko Index to Volume 109 Vo l. 109, No . 4, Wi nt er 2014 The Journal of the Maryland Historical Society Friends of the Press of the Maryland Historical Society The Maryland Historical Society continues its commitment to publish the finest new work in Maryland history. Next year, 2015, marks ten years since the Publications Committee, with the advice and support of the development staff, launched the Friends of the Press, an effort dedicated to raising money to be used solely for bringing new titles into print. The society is particularly grateful to H. Thomas Howell, past committee chair, for his unwavering support of our work and for his exemplary generosity. The committee is pleased to announce two new titles funded through the Friends of the Press. Rebecca Seib and Helen C. Rountree’s forthcoming Indians of Southern Maryland, offers a highly readable account of the culture and history of Maryland’s native people, from prehistory to the early twenty-first century. The authors, both cultural anthropologists with training in history, have written an objective, reliable source for the general public, modern Maryland Indians, schoolteachers, and scholars. -

Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment As Justice of the Peace

Catholic University Law Review Volume 45 Issue 2 Winter 1996 Article 2 1996 Marbury's Travail: Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment as Justice of the Peace. David F. Forte Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation David F. Forte, Marbury's Travail: Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment as Justice of the Peace., 45 Cath. U. L. Rev. 349 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol45/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES MARBURY'S TRAVAIL: FEDERALIST POLITICS AND WILLIAM MARBURY'S APPOINTMENT AS JUSTICE OF THE PEACE* David F. Forte** * The author certifies that, to the best of his ability and belief, each citation to unpublished manuscript sources accurately reflects the information or proposition asserted in the text. ** Professor of Law, Cleveland State University. A.B., Harvard University; M.A., Manchester University; Ph.D., University of Toronto; J.D., Columbia University. After four years of research in research libraries throughout the northeast and middle Atlantic states, it is difficult for me to thank the dozens of people who personally took an interest in this work and gave so much of their expertise to its completion. I apologize for the inevita- ble omissions that follow. My thanks to those who reviewed the text and gave me the benefits of their comments and advice: the late George Haskins, Forrest McDonald, Victor Rosenblum, William van Alstyne, Richard Aynes, Ronald Rotunda, James O'Fallon, Deborah Klein, Patricia Mc- Coy, and Steven Gottlieb. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1942, Volume 37, Issue No. 3

G ^ MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. XXXVII SEPTEMBER, 1942 No. } BARBARA FRIETSCHIE By DOROTHY MACKAY QUYNN and WILLIAM ROGERS QUYNN In October, 1863, the Atlantic Monthly published Whittier's ballad, "' Barbara Frietchie." Almost immediately a controversy arose about the truth of the poet's version of the story. As the years passed, the controversy became more involved until every period and phase of the heroine's life were included. This paper attempts to separate fact from fiction, and to study the growth of the legend concerning the life of Mrs. John Casper Frietschie, nee Barbara Hauer, known to the world as Barbara Fritchie. I. THE HEROINE AND HER FAMILY On September 30, 1754, the ship Neptune arrived in Phila- delphia with its cargo of " 400 souls," among them Johann Niklaus Hauer. The immigrants, who came from the " Palatinate, Darmstad and Zweybrecht" 1 went to the Court House, where they took the oath of allegiance to the British Crown, Hauer being among those sufficiently literate to sign his name, instead of making his mark.2 Niklaus Hauer and his wife, Catherine, came from the Pala- tinate.3 The only source for his birthplace is the family Bible, in which it is noted that he was born on August 6, 1733, in " Germany in Nassau-Saarbriicken, Dildendorf." 4 This probably 1 Hesse-Darmstadt, and Zweibriicken in the Rhenish Palatinate. 2 Ralph Beaver Strassburger, Pennsylvania German Pioneers (Morristown, Penna.), I (1934), 620, 622, 625; Pennsylvania Colonial Records, IV (Harrisburg, 1851), 306-7; see Appendix I. 8 T. J. C, Williams and Folger McKinsey, History of Frederick County, Maryland (Hagerstown, Md., 1910), II, 1047. -

History of Maryland

s^%. aVs*^-^^ :^\-'"^;v^'^v ..-Jy^^ ..- 'A S "00^ X^^.. * ti. •/-- * •) O \V 1 ^ -V n „ S V ft /. ^ 'f ^^. "'TV^^ .x\ ^ s? HISTORY O F MAKYLAND; FROM ITS FIRST SETTLEMENT IN 1634, YEAR 1848. BY JAMES McS KERRY SECOND EDITION, RF.VISED AND CORRECTED BY THE AUTHOR. BALTIMORE: PRINTED AND tUULISHED BYJOHN MURPHY, No. 178 Market Street. 80LD.B7 BOOKSELLERS GENERALLT MDCCC;CLIX. } / d Entered, according to the act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and forty-nine, by John Murphy, in the clerk's office of the District Court of Maryland. JOHN MURPHY, Printer, Baltimore. WM. H. HOPE, Stereotyper. YOUTH OF MARYLAND, /"C'^^THIS B O O K ,r^:^^=p-\ IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED, \^C-;^^ IN THE HOPE, ^^^j^^ THAT ITS PERUSAL MAY IMPRESS UPON THEIR MINDS ^S^* ^^isforg of i^nv ^^«*tbe ^^'f<tf<, STRENGTHEN THAT DUTIFUL AND PATRIOTIC LOVE -WHICH THEY OWE IT, AND INDUCE THEM TO ADMIRE AND IMITATE THE VIRTUE, THE VALOUR, AND THE LIBERALITY, THEIR FOREFATHERS. — PREFACE. In this work the author has endeavored to compress together, in a popular form, such events in the history of Maryhmd as would interest the general reader, and to give a simple narration of the settlement of the colony; its rise and progress ; its troubles and revolutions ; as well as the long periods of peace and serenity, which beautified its early days : —to picture the beginning, the progress, and the happy conclusion of the war of independence—the forti- tude and valor of the sons of Maryland upon the field, and their wisdom in council. -

Bk Adbl 016864.Pdf

InternalEnemy_7pp.indd 4 7/3/13 12:40 PM T C R, CUMBERLAND LANCASTER BEDFORD YORK Su CHESTER sq PENNSYLVANIA u e h GLOUCESTER a n n HARFORD a CECIL Delaware R. R SALEM FREDERICK . Havre de Grace Frenchtown NEW BERKELEY MARYLAND NEW JERSEY HAMPSHIRE Frederick BALTIMORE CASTLE CUMBERLAND Baltimore Georgetown KENT FREDERICK Chestertown D ANNE ARUNDEL e l Winchester KENT a Poto Kent QUEEN w LOUDOUN ma Island ANNES a c R r . e B Annapolis a y Washington, D.C. CAROLINE TALBOT DUNMORE FAIRFAX PRINCE GEORGE'S FAUQUIER Alexandria DELAWARE PRINCE WILLIAM P a t u CALVERT VIRGINIA x e SUSSEX CHARLES n Benedict t CULPEPER R STAFFORD . C DORCHESTER Rappahanno h ck e R. s Chaptico a SOMERSET p KING Fredericksburg ST. e GEORGE MARY'S CO. a T k ORANGE SPOTSYLVANIA e WORCESTER M N a WESTMORELAND B N tt a a p Nomini Ferry o y O n i Charlottesville LOUISA Kinsale CAROLINE R M . RICHMOND Tappahannock E NORTHUMBERLAND R ALBEMARLE D ESSEX P O amu LANCASTER E nk Tangier ACCOMACK e H y R KING AND Island I HANOVER . S QUEEN GOOCHLAND KING Chesconessex Cr. P WILLIAM BUCKINGHAM James River Corotoman NPungoteague Creek R MIDDLESEX CUMBERLAND York R. Gwynn E E R. E T tox Richmond HENRICO NEW KENT Island at S m MATHEWS H o H p A p JAMES GLOUCESTER A CHESTERFIELD CHARLES CITY E NORTHAMPTON CO. T T CITY Williamsburg New Point PRINCE AMELIA PRINCE GEORGE Yorktown Comfort EDWARD Petersburg YORK NEWPORT DINWIDDIE SURRY NEWS HAMPTON Hampton LUNENBURG ISLE OF SUSSEX WIGHT Norfolk Lynnhaven Bay PRINCESS BRUNSWICK ANNE CO. -

Jonathan D. Meredith Papers

Jonathan D. Meredith Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Theresa Salazar Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2012 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2012 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms012148 Collection Summary Title: Jonathan D. Meredith Papers Span Dates: 1795-1859 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1810-1859) ID No.: MSS32664 Creator: Meredith, Jonathan, 1783-1872 Extent: 9,000 items ; 15 containers plus 1 oversize ; 6 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Lawyer, army officer, and businessman of Baltimore, Md. Family and general correspondence, legal files, financial papers, and other material relating chiefly to Meredith's associations with the Savings Bank of Baltimore and the Bank of the United States; the War of 1812; impeachment proceedings against James Hawkins Peck; shipping and trade with Europe and South America; and settlement of the estates of Charles Carroll and Robert Oliver. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Aspinwall, William Henry, 1807-1875--Correspondence. Calderón de la Barca, Ángel--Correspondence. Carroll, Charles, 1737-1832--Estate. Cogswell, Joseph Green, 1786-1871--Correspondence. Duane, William J. (William John), 1780-1865--Correspondence. Gilmor, Robert, 1748-1822--Correspondence. Graham, John, 1774-1820--Correspondence. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1911, Volume 6, Issue No. 2

/V\5A.SC 5^1- i^^ MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE Voi,. VI. JUNE, 1911. No. 2. THE MARYLAND GUARD BATTALION, 1860-61.1 ISAAC F. NICHOLSON. (Bead before the Society April 10, 1911.) After an interval of fifty years, it is permitted the writer to avail of the pen to present to a new generation a modest record of a military organization of most brilliant promise— but whose career was brought to a sudden close after a life of but fifteen months. The years 1858 and 1859 were years of very grave import in the history of our city. Local political conditions had become almost unendurable, the oitizens were intensely incensed and outraged, and were one to ask for a reason for the formation of an additional military organization in those days, a simple reference to the prevailing conditions would be ample reply. For several years previous the City had been ruled by the American or Know Nothing Party who dominated it by violence through the medium of a partisan police and disorderly political clubs. No man of opposing politics, however respectable, ever undertook to cast his vote without danger to his life. 'The corporate name of this organization was "The Maryland Guard" of Baltimore City. Its motto, " Decus et Prsesidium." 117 118 MAEYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZIlfE. The situation was intolerable, and the State at large having gone Democratic, some of our best citizens turned to the Legis- lature for relief and drafted and had passed an Election Law which provided for fair elections, and a Police Law, which took the control of that department from the City and placed it in the hands of the State. -

Timeline of John Hanson's Life, Roles in the Birth of the United States, Presidency and Remembrances Since His Death

Timeline of John Hanson's Life, Roles In the Birth of the United States, Presidency and Remembrances Since His Death Early and Midlife of John Hanson April 3, 1715 Born at Mulberry Grove, the Hanson ancestral home in Charles County, Mary- land, “about 2 or 3 in ye afternoon,” son of Judge Samuel Hanson and Elizabeth Story Hanson, and grandson of his immigrant namesake Probably ≈1730-35 Said to have studied at Oxford 1743 Marries Jane Contee Hanson 1750 Appointed as Sheriff of Charles County, Maryland. 1757-58, 65-66, 68 Represents Charles County in the Maryland Assembly February 14, 1758 Appointed by Maryland Assembly to two finance committees beginning Hanson's role of increasing specialization and prominence in the field of public finance During Hanson's time Becomes a leader of the Country Party which seeks more colonial rights and in the Maryland stands in opposition to the Proprietary Party which owes allegiance to the Mary- House of Delegates land Proprietor, the chief agent of the British government in Maryland March 22, 1765 British Parliament passes the Stamp Act taxing the North American colonies September 23, 1765 The Maryland Assembly meets to discuss the Stamp Act after having been for- bidden by the British to meet in 1764 September 24, 1765 John Hanson one of seven appointed by the Maryland Assembly to draft instruc- tions for the Assembly's delegates to the colonies' Stamp Act Congress October, 1765 Stamp Act Congress, a meeting of the colonies to oppose the Stamp Act, meets November 1, 1765 Stamp Act takes effect.