The Army of Tennessee in War and Memory, 1861-1930

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle to Interpret Arlington House, 1921–1937,” by Michael B

Welcome to a free reading from Washington History: Magazine of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. As we chose this week’s reading, news stories continued to swirl about commemorative statues, plaques, street names, and institutional names that amplify white supremacy in America and in DC. We note, as the Historical Society fulfills its mission of offering thoughtful, researched context for today’s issues, that a key influence on the history of commemoration has come to the surface: the quiet, ladylike (in the anachronistic sense) role of promoters of the southern “Lost Cause” school of Civil War interpretation. Historian Michael Chornesky details how federal officials fended off southern supremacists (posing as preservationists) on how to interpret Arlington House, home of George Washington’s adopted family and eventually of Confederate commander Robert E. Lee. “Confederate Island upon the Union’s ‘Most Hallowed Ground’: The Battle to Interpret Arlington House, 1921–1937,” by Michael B. Chornesky. “Confederate Island” first appeared in Washington History 27-1 (spring 2015), © Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Access via JSTOR* to the entire run of Washington History and its predecessor, Records of the Columbia Historical Society, is a benefit of membership in the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. at the Membership Plus level. Copies of this and many other back issues of Washington History magazine are available for browsing and purchase online through the DC History Center Store: https://dchistory.z2systems.com/np/clients/dchistory/giftstore.jsp ABOUT THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON, D.C. The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is a non-profit, 501(c)(3), community-supported educational and research organization that collects, interprets, and shares the history of our nation's capital in order to promote a sense of identity, place and pride in our city and preserve its heritage for future generations. -

Brochure Design by Communication Design, Inc., Richmond, VA 877-584-8395 Cheatham Co

To Riggins Hill CLARKSVILLE MURFREESBORO and Fort Defiance Scroll flask and .36 caliber Navy Colt bullet mold N found at Camp Trousdale . S P R site in Sumner County. IN G Stones River S T Courtesy Pat Meguiar . 41 National Battlefield The Cannon Ball House 96 and Cemetery in Blountville still 41 Oaklands shows shell damage to Mansion KNOXVILLE ST. the exterior clapboard LEGE Recapture of 441 COL 231 Evergreen in the rear of the house. Clarksville Cemetery Clarksville 275 40 in the Civil War Rutherford To Ramsey Surrender of ST. County Knoxville National Cemetery House MMERCE Clarksville CO 41 96 Courthouse Old Gray Cemetery Plantation Customs House Whitfield, Museum Bradley & Co. Knoxville Mabry-Hazen Court House House 231 40 “Drawing Artillery Across the Mountains,” East Tennessee Saltville 24 Fort History Center Harper’s Weekly, Nov. 21, 1863 (Multiple Sites) Bleak House Sanders Museum 70 60 68 Crew repairing railroad Chilhowie Fort Dickerson 68 track near Murfreesboro 231 after Battle of Stones River, 1863 – Courtesy 421 81 Library of Congress 129 High Ground 441 Abingdon Park “Battle of Shiloh” – Courtesy Library of Congress 58 41 79 23 58 Gen. George H. Thomas Cumberland 421 Courtesy Library of Congress Gap NHP 58 Tennessee Capitol, Nashville, 1864 Cordell Hull Bristol Courtesy Library of Congress Adams Birthplace (East Hill Cemetery) 51 (Ft. Redmond) Cold Spring School Kingsport Riggins Port Royal Duval-Groves House State Park Mountain Hill State Park City 127 (Lincoln and the 33 Blountville 79 Red Boiling Springs Affair at Travisville 431 65 Portland Indian Mountain Cumberland Gap) 70 11W (See Inset) Clarksville 76 (Palace Park) Clay Co. -

United Confederate Veterans Association Records

UNITED CONFEDERATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION RECORDS (Mss. 1357) Inventory Compiled by Luana Henderson 1996 Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana Revised 2009 UNITED CONFEDERATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION RECORDS Mss. 1357 1861-1944 Special Collections, LSU Libraries CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE ...................................................................................... 4 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF SUBGROUPS AND SERIES ......................................................................................... 7 SUBGROUPS AND SERIES DESCRIPTIONS ............................................................................ 8 INDEX TERMS ............................................................................................................................ 13 CONTAINER LIST ...................................................................................................................... 15 APPENDIX A ............................................................................................................................... 22 APPENDIX B ............................................................................................................................. -

Civil War Battles in Tennessee

Civil War Battles in Tennessee Lesson plans for primary sources at the Tennessee State Library & Archives Author: Rebecca Byrd, New Center Elementary Grade Level: 5th grade Date Created: May 2018 Visit http://sos.tn.gov/tsla/education for additional lesson plans. Civil War Battles in Tennessee Introduction: Tennessee’s Civil War experience was unique. Tennessee was the last state to se- cede and the first to rejoin the Union. Middle and West Tennessee supported secession by and large, but the majority of East Tennessee opposed secession. Ironically, Middle and West Tennessee came under Union control early in the war, while East Tennessee remained in Confederate hands. Tennessee is second only to Virginia in number of battles fought in the state. In this lesson, students will explore the economic and emotional effects of the war on the citizens of Tennessee. Guiding Questions How can context clues help determine an author’s point of view? How did Civil War battles affect the short term and long term ability of Tennesseans to earn a living? How did Civil War battles affect the emotions of Tennesseans? Learning Objectives The learner will analyze primary source documents to determine whether the creator/author supported the Union or Confederacy. The learner will make inferences to determine the long term and short term economic effects of Civil War battles on the people of Tennessee. The learner will make inferences to determine the emotional affect the Civil War had on Tennesseans. 1 Curriculum Standards: SSP.02 Critically examine -

List of Staff Officers of the Confederate States Army. 1861-1865

QJurttell itttiuetsity Hibrary Stliaca, xV'cni tUu-k THE JAMES VERNER SCAIFE COLLECTION CIVIL WAR LITERATURE THE GIFT OF JAMES VERNER SCAIFE CLASS OF 1889 1919 Cornell University Library E545 .U58 List of staff officers of the Confederat 3 1924 030 921 096 olin The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030921096 LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES ARMY 1861-1865. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1891. LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE ARMY. Abercrombie, R. S., lieut., A. D. C. to Gen. J. H. Olanton, November 16, 1863. Abercrombie, Wiley, lieut., A. D. C. to Brig. Gen. S. G. French, August 11, 1864. Abernathy, John T., special volunteer commissary in department com- manded by Brig. Gen. G. J. Pillow, November 22, 1861. Abrams, W. D., capt., I. F. T. to Lieut. Gen. Lee, June 11, 1864. Adair, Walter T., surg. 2d Cherokee Begt., staff of Col. Wm. P. Adair. Adams, , lieut., to Gen. Gauo, 1862. Adams, B. C, capt., A. G. S., April 27, 1862; maj., 0. S., staff General Bodes, July, 1863 ; ordered to report to Lieut. Col. R. G. Cole, June 15, 1864. Adams, C, lieut., O. O. to Gen. R. V. Richardson, March, 1864. Adams, Carter, maj., C. S., staff Gen. Bryan Grimes, 1865. Adams, Charles W., col., A. I. G. to Maj. Gen. T. C. Hiudman, Octo- ber 6, 1862, to March 4, 1863. Adams, James M., capt., A. -

Timeline 1864

CIVIL WAR TIMELINE 1864 January Radical Republicans are hostile to Lincoln’s policies, fearing that they do not provide sufficient protection for ex-slaves, that the 10% amnesty plan is not strict enough, and that Southern states should demonstrate more significant efforts to eradicate the slave system before being allowed back into the Union. Consequently, Congress refuses to recognize the governments of Southern states, or to seat their elected representatives. Instead, legislators begin to work on their own Reconstruction plan, which will emerge in July as the Wade-Davis Bill. [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/reconstruction/states/sf_timeline.html] [http://www.blackhistory.harpweek.com/4Reconstruction/ReconTimeline.htm] Congress now understands the Confederacy to be the face of a deeply rooted cultural system antagonistic to the principles of a “free labor” society. Many fear that returning home rule to such a system amounts to accepting secession state by state and opening the door for such malicious local legislation as the Black Codes that eventually emerge. [Hunt] Jan. 1 TN Skirmish at Dandridge. Jan. 2 TN Skirmish at LaGrange. Nashville is in the grip of a smallpox epidemic, which will carry off a large number of soldiers, contraband workers, and city residents. It will be late March before it runs its course. Jan 5 TN Skirmish at Lawrence’s Mill. Jan. 10 TN Forrest’s troops in west Tennessee are said to have collected 2,000 recruits, 400 loaded Wagons, 800 beef cattle, and 1,000 horses and mules. Most observers consider these numbers to be exaggerated. “ The Mississippi Squadron publishes a list of the steamboats destroyed on the Mississippi and its tributaries during the war: 104 ships were burned, 71 sunk. -

Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett

Spring Grove Cemetery, once characterized as blending "the elegance of a park with the pensive beauty of a burial-place," is the final resting- place of forty Cincinnatians who were generals during the Civil War. Forty For the Union: Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett f the forty Civil War generals who are buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, twenty-three had advanced from no military experience whatsoever to attain the highest rank in the Union Army. This remarkable feat underscores the nature of the Northern army that suppressed the rebellion of the Confed- erate states during the years 1861 to 1865. Initially, it was a force of "inspired volunteers" rather than a standing army in the European tradition. Only seven of these forty leaders were graduates of West Point: Jacob Ammen, Joshua H. Bates, Sidney Burbank, Kenner Garrard, Joseph Hooker, Alexander McCook, and Godfrey Weitzel. Four of these seven —Burbank, Garrard, Mc- Cook, and Weitzel —were in the regular army at the outbreak of the war; the other three volunteered when the war started. Only four of the forty generals had ever been in combat before: William H. Lytle, August Moor, and Joseph Hooker served in the Mexican War, and William H. Baldwin fought under Giuseppe Garibaldi in the Italian civil war. This lack of professional soldiers did not come about by chance. When the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787, its delegates, who possessed a vast knowledge of European history, were determined not to create a legal basis for a standing army. The founding fathers believed that the stand- ing armies belonging to royalty were responsible for the endless bloody wars that plagued Europe. -

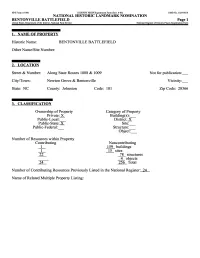

BENTONVILLE BATTLEFIELD Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION BENTONVILLE BATTLEFIELD Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: BENTONVILLE BATTLEFIELD Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Along State Routes 1008 & 1009 Not for publication: City/Town: Newton Grove & Bentonville Vicinity: State: NC County: Johnston Code: 101 Zip Code: 28366 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: JL Building(s):__ Public-Local:__ District: X Public-State:JL Site:__ Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing _1_ 159 buildings _1_ 15 sites 22 78 structures ___ 4 objects 24 256 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 24 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BENTONVILLE BATTLEFIELD Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

George Henry Thomas (July 31, 1816 – March 28, 1870)

George Henry Thomas (July 31, 1816 – March 28, 1870) "Rock of Chickamauga" "Sledge of Nashville" "Slow Trot Thomas" The City of Fort Thomas was named in honor of Major General George Henry Thomas, who ranks among the top Union Generals of the American Civil War. He was born of Welsh/English and French parents in Virginia on July 31, 1816, and was educated at Southampton Academy. Prior to his military service Thomas studied law and worked as a law deputy for his uncle, James Rochelle, the Clerk of the County Court before he received an appointment to West Point in 1836. He graduated 12th in his class of 42 in 1840 which William T. Sherman was a classmate. After receiving his commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 3rd Artillery Unit, he served the Army well for the next 30 years. He was made 1st Lieutenant for action against the Indians in Florida for his gallantry in action. In the Mexican War, he served under Braxton Bragg in the Artillery and was twice cited for gallantry—once at Monterey and the other at Buena Vista. From 1851-1854 was an instructor of artillery and cavalry at West Point, where he was promoted to Captain. Following his service at Ft. Yuma in the West, he became a Major and joined the 2nd Cavalry at Jefferson Barracks. The Colonel there was Albert Sidney Johnston and Robert E. Lee was the Lt. Colonel. Other officers in this regiment who were to become famous as Generals were George Stoneman, for the Union, and for the CSA, John B. -

Chickamauga the Battle

Chickamauga the Battle, Text and Photographs By Dennis Steele Senior Staff Writer he Battle of Chickamauga flashed into a white-hot clash on September 19, 1863, following engagements in Teastern and central Tennessee and northern Mississippi that caused the withdrawal of the Confederate Army of Tennessee (renamed from the Army of Mississippi) under GEN Braxton Bragg to Chattanooga, Tenn. Bragg was forced to make a further withdrawal into northwest Georgia after the Union’s Army of the Cumberland, under MG William S. Rosecrans, crossed the Tennessee River below Chattanooga, flanking Bragg’s primary line of defense. Chattanooga was a strategic prize. Union forces needed it as a transportation hub and supply center for the planned campaign into Georgia. The South needed the North not to have it. At LaFayette, Ga., about 26 miles south of Chattanooga, Bragg received reinforcements. After preliminary fights to stop Rosecrans, he crossed Chickamauga Creek to check the Union advance. In two days of bloody fighting, Bragg gained a tactical victory over Rosecrans at Chickamauga, driving the Army of the Cumberland from the battlefield. The stage was set for Bragg to lose the strategic campaign for Chattanooga, however, as he failed to pursue the retreating Union force, allowing it to withdraw into Chattanooga behind a heroic rear-guard stand by a force assembled from the disarray by MG George H. Thomas. The Battle of Chickamauga is cited as the last major Southern victory of the Civil War in the Western Theater. It bled both armies. Although official records are sketchy in part, estimates put Northern casualties at around 16,200 and Southern casualties at around 18,000. -

Chapter One: the Campaign for Chattanooga, June to November 1863

CHAPTER ONE: THE CAMPAIGN FOR CHATTANOOGA, JUNE TO NOVEMBER 1863 Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park commemorates and preserves the sites of important and bloody contests fought in the fall of 1863. A key prize in the fighting was Chattanooga, Tennessee, an important transportation hub and the gateway to Georgia and Alabama. In the Battle of Chickamauga (September 18-20, 1863), the Confederate Army of Tennessee soundly beat the Federal Army of the Cumberland and sent it in full retreat back to Chattanooga. After a brief siege, the reinforced Federals broke the Confeder- ate grip on the city in a series of engagements, known collectively as the Battles for Chatta- nooga. In action at Brown’s Ferry, Wauhatchie, and Lookout Mountain, Union forces eased the pressure on the city. Then, on November 25, 1863, Federal troops achieved an unex- pected breakthrough at Missionary Ridge just southeast of Chattanooga, forcing the Con- federates to fall back on Dalton, Georgia, and paving the way for General William T. Sherman’s advance into Georgia in the spring of 1864. These battles having been the sub- ject of exhaustive study, this context contains only the information needed to evaluate sur- viving historic structures in the park. Following the Battle of Stones River (December 31, 1862-January 2, 1863), the Federal Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Major General William S. Rosecrans, spent five and one-half months at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, reorganizing and resupplying in preparation for a further advance into Tennessee (Figure 2). General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee was concentrated in the Tullahoma, Tennessee, area. -

Chapter 11: the Civil War, 1861-1865

The Civil War 1861–1865 Why It Matters The Civil War was a milestone in American history. The four-year-long struggle determined the nation’s future. With the North’s victory, slavery was abolished. During the war, the Northern economy grew stronger, while the Southern economy stagnated. Military innovations, including the expanded use of railroads and the telegraph, coupled with a general conscription, made the Civil War the first “modern” war. The Impact Today The outcome of this bloody war permanently changed the nation. • The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery. • The power of the federal government was strengthened. The American Vision Video The Chapter 11 video, “Lincoln and the Civil War,” describes the hardships and struggles that Abraham Lincoln experienced as he led the nation in this time of crisis. 1862 • Confederate loss at Battle of Antietam 1861 halts Lee’s first invasion of the North • Fort Sumter fired upon 1863 • First Battle of Bull Run • Lincoln presents Emancipation Proclamation 1859 • Battle of Gettysburg • John Brown leads raid on federal ▲ arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia Lincoln ▲ 1861–1865 ▲ ▲ 1859 1861 1863 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1861 1862 1863 • Russian serfs • Source of the Nile River • French troops 1859 emancipated by confirmed by John Hanning occupy Mexico • Work on the Suez Czar Alexander II Speke and James A. Grant City Canal begins in Egypt 348 Charge by Don Troiani, 1990, depicts the advance of the Eighth Pennsylvania Cavalry during the Battle of Chancellorsville. 1865 • Lee surrenders to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse • Abraham Lincoln assassinated by John Wilkes Booth 1864 • Fall of Atlanta HISTORY • Sherman marches ▲ A.