Epictetus a Stoic and Socratic Guide to Life Print ISBN 0199245568, 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

Timothy Williamson: Publications in reverse chronological order In preparation [a] ‘Knowledge, credence, and strength of belief’, invited for Amy Flowerree and Baron Reed (eds.), The Epistemic. [b] ‘Blackburn against moral realism’, for Paul Bloomfield and David Copp (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Moral Realism, Oxford University Press. [c] ‘Non-modal normativity and norms of belief’, for Ilkka Niiniluoto and Sami Pihlstrom (eds.), volume on normativity, Acta Philosophica Fennica (2020). [d] ‘The KK principle and rotational symmetry’, invited for Analytic Philosophy. [e] ‘Chakrabarti and the Nyāya on knowability’. To appear [a] Suppose and Tell: The Semantics and Heuristics of Conditionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020. [b] (with Paul Boghossian) Debating the A Priori. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020. [c] ‘Edgington on possible knowledge of unknown truth’, in J. Hawthorne and L. Walters (eds.), Conditionals, Probability, and Paradox: Themes from the Philosophy of Dorothy Edgington, Oxford: Oxford University Press. [d] ‘Justifications, excuses, and skeptical scenarios’, in J. Dutant and F. Dorsch (eds.), The New Evil Demon, Oxford University Press. [e] ‘The counterfactual-based approach to modal epistemology’, in Otávio Bueno and Scott Shalkowski (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Modality, London: Routledge. [f] ‘More Oxonian scepticism about the a priori’, in Dylan Dodd and Elia Zardini (eds.), The A Priori: Its Significance, Grounds, and Extent, Oxford University Press. [g] ‘Reply to Casullo’s defence of the significance of the a priori – a posteriori distinction’, in Dylan Dodd and Elia Zardini (eds.), The A Priori: Its Significance, Grounds, and Extent, Oxford University Press. [h] ‘Introduction’ to Khaled Qutb, Summary of The Philosophy of Philosophy (in Arabic), Cairo: Academic Bookshop. -

Commentary on Englert Martha Nussbaum I Admire Englert's

Commentary on Englert Martha Nussbaum I admire Englert's paper. I find its major conclusions entirely convincing: (1) the analysis of the difference between Epicurean and Stoic attitudes to suicide; (2) the account of the original Stoic position; (3) the argument that Seneca is an orthodox Stoic about suicide; and (4) the very interesting claims about the role of dif- ferent sorts of freedom in Seneca's arguments. Although I am persuaded by his analysis, I am inclined to be somewhat more critical of the Stoic position than he seems inclined to be: for I think that in a crucial way it is internally incoherent. In what follows, therefore, I want to focus on a problem in the Stoic account itself, with respect to the ambivalence the suicide theory reveals toward the importance of externals. I shall do this by focusing on one line of argument leading to suicide, in Seneca's De Ira.l 1. The Stoics famously hold that only virtue is worth choosing for its own sake. And virtue all by itself suffices for a complete- ly fulfilled and fulfilling human life, that is, for eudaimonia. Virtue is something unaffected by external contingency—both, apparently, as to its acquisition and as to its maintenance once acquired? Items that are not fully under the control of the 1. My interpretation of this work is developed at greater length in Nussbaum 1994. My general account of Stoic virtue theory and its relationship to the call for the extirpation of passion is in chapter 10, my detailed analysis of the argu- ments about anger in the De Ira in chapter 11. -

The Hymn of Cleanthes Greek Text Translated Into English

UC-NRLF 557 C29 ^ 033 TDt. 3 + 1921 3• MAIN ^ ft (9 -- " EXTS FOR STUDENTS, No. 26 THE YMN OF CLEANTHES GREEK TEXT TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH BRIEF INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY E. H. BLAKENEY, M.A. ce 6d. net. HELPS FOR STUDENTS OF HISTORY. 1. EPISCOPAL REGISTERS OF ENGLAND AND WALES. By R. C. Fowler, B.A., F.S.A. 6d. net. 2. MUNICIPAL RECORDS. By F. J. C. Hearnsuaw, M.A. Gd. net. 3. MEDIEVAL RECKONINGS OF TIME. ' By Reginald L. Poole, LL.D., Litt.D. 6d. net. % 4. THE PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE. By Charles Johnson. 6d. net. 5. THE CARE OF DOCUMENTS. By Charles Johnson. 6d.net. 6. THE LOGIC OF HISTORY. By C. G. Cramp. 8d.net. 7. DOCUMENTS IN THE PUBUC RECORD OFFICE, DUBLIN. By B. H. Murray, Litt.D. 8d. net. 8. THE FRENCH WARS OF RELIGION. By Arthur A. TiUey» M.A. 6d. net. By Sir A. W. WARD, Litt.D., F.B.A. 9. THE PERIOD OF CONGRESSES, I. Introductory. 8d.net. 10. THE PERIOD OF CONGRESSES, II. Vienna and the Second Peace of Paris. Is. net. 11. THE PERIOD OF CONGRESSES, IH. Aix-la-ChapeUe to Verona. Is. net. (Nos. 9, 10, and 11 in one volume, cloth, 3s. Gd. net.) 12. SECURITIES OF PEACE. A Retrospect (1848-1914). Paper, 2s. ; cloth, 3s. net. 13. THE FRENCH RENAISSANCE. By Arthur A. TiUey, M.A* 8d. net. 14. HINTS ON THE STUDY OF ENGUSH ECONOMIC HISTORY. By W. Cunningham, D.D., F.B.A., F.S.A. 8d. net. 1 5. PARISH HISTORY AND RECORDS. -

166 BOOK REVIEWS Gretchen Reydams-Schils, the Roman Stoics

166 BOOK REVIEWS Gretchen Reydams-Schils, The Roman Stoics: Self, Responsibility and Affection. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2005. xii + 210 pp. ISBN 0-226-30837-5. In the third book of the Histones Tacitus presents us with the ludicrous picture of a Stoic philosopher mingling with the soldiers of the Flavian army as it prepares to invade the city, and preaching unheeded the blessings of peace and the dangers of war (3.81). The purveyor of this intempestiva sapientia was Musonius Rufus, an eques Romanus, a friend of many Roman senators, a political exile, and the hero of this book. The author sets out to prove that the Roman Stoics adapted originally Greek Stoic doctrine to emphasize the importance of social responsibility and social engagement to the life of virtue. Stoicism, for all its emphasis on self-sufficiency, independence of outer circumstances, and spiritual self-improvement, saw the instinct for sociability as implanted by divine providence in human beings, who were imbedded in a society of rational beings comprising men and gods. What the author thinks was the distinctive contribution of the Roman Stoics was to retrieve for the life of virtue the traditional relationships of parenthood and marriage that Plato and the Cynics had tried to denigrate. It is therefore not the Musonius Rufus of Roman politics that interests her, but the advocate of marriage as a union of body and soul between equals and the opponent of infanticide and child exposure. The structure of the book reflects this emphasis, for it ‘reverses the Stoic progression from self to god and universe’ (5). -

Gillian K. Russell

Gillian K. Russell Dianoia Institute of Philosophy (cell) +1 (858) 205{2834 Locked Bag 4115 MDC [email protected] Fitzroy, Victoria 3065 https://www.gillianrussell.net Australia Current Employment Professor of Philosophy Dianoia Institute at ACU in Melbourne 2020| 1 Arch´eProfessorial Fellow ( 5 th time) University of St Andrews, Scotland 2019{2023 Employment and Education History Alumni Distinguished Professor University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2019{2020 Professor of Philosophy University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2015{19 Associate Professor in Philosophy Washington University in St Louis 2011{2015 Assistant Professor in Philosophy Washington University in St Louis 2004{2011 Killam Postdoctoral Fellow University of Alberta 2005 Ph.D. in Philosophy Princeton University 2004 M.A. in Philosophy Princeton University 2002 M.A. in German and Philosophy University of St Andrews, Scotland 1999 Areas of Specialisation Philosophy of Language, Philosophy of Logic, Epistemology Areas of Competence Logic, History of Analytic Philosophy, Metaphysics, Philosophy of Science and Mathematics Books { Truth in Virtue of Meaning: a defence of the analytic/synthetic distinction (Oxford, 2008) { The Routledge Companion to the Philosophy of Language, with Delia Graff Fara (eds.) (Routledge, 2011) { New Waves in Philosophical Logic, with Greg Restall (eds.) (Palgrave MacMillan, 2012) Accepted and Published Papers { \Social Spheres" forthcoming in Feminist Philosophy and Formal Logic Audrey Yap and Roy Cook (eds) { \Logic: A Feminist Approach" forthcoming in Philosophy for Girls: An invitation to the life of thought, M. Shew and K. Garchar (eds) (Oxford University Press, 2020) { \Waismann's Papers on the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction" in Friedrich Waismann: The Open Texture of Analytic Philosophy, D. -

Readingsample

Studies on Ancient Moral and Political Philosophy 1 What is Up to Us? Studies on Agency and Responsibility in Ancient Philosophy von Edited by Pierre Destrée, Ricardo Salles 1. Academia Verlag St. Augustin bei Bonn 2014 Verlag C.H. Beck im Internet: www.beck.de ISBN 978 3 89665 634 6 Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei beck-shop.de DIE FACHBUCHHANDLUNG Pierre Destrée, Ricardo Salles and Marco Zingano 1 Introduction Pierre Destrée, Ricardo Salles and Marco Zingano The present volume brings together twenty contributions whose aim is to study the problem of moral responsibility as it arises in Antiquity in connection with the concept of what depends on us, or is up to us, through the expression eph’ hêmin and its Latin synonyms in nostra potestate and in nobis. The notion of what is up to us begins its philosophical lifetime with Aristotle. However, as the chapters by Monte Johnson and Pierre Destrée point out, it is already present in earlier authors such as Democritus and Plato, who clearly raise some of the issues that were linked to this notion in the later tradition. In Aristotle, the expression eph’ hêmin is frequently used in the plural to denote the things that are up to us in the sense that they are in our power to do or not to do. It plays a central role in his action theory insofar as the scope of deliberate choice is specifi- cally the set of these things (we deliberate about how to bring about things that it is up to us to achieve). -

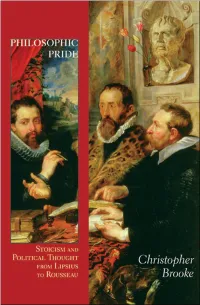

Stoicism and Political Thought from Lipsius to Rousseau

Philosophic Pride Brooke.indb 1 1/17/2012 12:09:47 PM This page intentionally left blank Brooke.indb 2 1/17/2012 12:09:47 PM Philosophic Pride stoicism and political thought from lipsius to rousseau Christopher Brooke princeton university press Princeton and Oxford Brooke.indb 3 1/17/2012 12:09:47 PM Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu Jacket illustration: The Four Philosophers, c. 1611–12 (oil on panel), by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640); Palazzo Pitti, Florence, Italy. Reproduced courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library; photo copyright Alinari All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brooke, Christopher, 1973– Philosophic pride : Stoicism and political thought from Lipsius to Rousseau / Christopher Brooke. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. 253) and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15208-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Political science—Philosophy— History. I. Title. JA71.B757 2012 320.01—dc23 2011034498 This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 00 Brooke FM i-xxiv.indd 4 1/24/2012 3:05:14 PM For Josephine Brooke.indb 5 1/17/2012 12:09:47 PM This page intentionally left blank The Stoic last in philosophic pride, By him called virtue, and his virtuous man, Wise, perfect in himself, and all possessing, Equal to God, oft shames not to prefer, As fearing God nor man, contemning all Wealth, pleasure, pain or torment, death and life— Which, when he lists, he leaves, or boasts he can; For all his tedious talk is but vain boast, Or subtle shifts conviction to evade. -

Stoic Enlightenments

Copyright © 2011 Margaret Felice Wald All rights reserved STOIC ENLIGHTENMENTS By MARGARET FELICE WALD A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in English written under the direction of Michael McKeon and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2011 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Stoic Enlightenments By MARGARET FELICE WALD Dissertation Director: Michael McKeon Stoic ideals infused seventeenth- and eighteenth-century thought, not only in the figure of the ascetic sage who grins and bears all, but also in a myriad of other constructions, shaping the way the period imagined ethical, political, linguistic, epistemological, and social reform. My dissertation examines the literary manifestation of Stoicism’s legacy, in particular regarding the institution and danger of autonomy, the foundation and limitation of virtue, the nature of the passions, the difference between good and evil, and the referentiality of language. Alongside the standard satirical responses to the ancient creed’s rigor and rationalism, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century poetry, drama, and prose developed Stoic formulations that made the most demanding of philosophical ideals tenable within the framework of common experience. Instead of serving as hallmarks for hypocrisy, the literary stoics I investigate uphold a brand of stoicism fit for the post-regicidal, post- Protestant Reformation, post-scientific revolutionary world. My project reveals how writers used Stoicism to determine the viability of philosophical precept and establish ways of compensating for human fallibility. The ambivalent status of the Stoic sage, staged and restaged in countless texts, exemplified the period’s anxiety about measuring up to its ideals, its efforts to discover the plenitude of ii natural laws and to live by them. -

Sport: a Theory of Adjudication

SPORT: A THEORY OF ADJUDICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bogdan Ciomaga, M.A. The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor William Morgan, Adviser Professor Donald Hubin ________________________ Adviser Professor Sarah Fields Graduate Program in Education Copyright by Bogdan Ciomaga 2007 ABSTRACT The main issue discussed in this work is the nature and structure of the process of adjudication, that is, the process by which referees make decisions in sport that possess normative import and force. The current dominant theory of adjudication in sport philosophy is interpretivism, which argues that adjudication is not primarily a matter of mechanically applying the rules of the game, but rather of applying rational principles that put the game in its best light. Most interpretivists are also realists, which means that they hold that the normative standing of adjudicative principles is independent of the beliefs and/or arguments of individuals or communities. A closer look at certain examples of sports and referees decisions supports a different approach to adjudication, called conventionalism, which claims that besides the rules of the game, referees are bound to follow certain conventions established by the athletic community. This conclusion is supported, among other things, by considerations concerning the nature of sport, and especially considerations that take into account the mutual beliefs held by the participants in the game. By following Marmor’s argument that conventions are best seen not as solutions to coordination problems but as constitutive features of autonomous practices like sport, I argue that a conventionalist theory of adjudication in sport has more explanatory force than interpretivist theories. -

The Stoics and the Practical: a Roman Reply to Aristotle

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2013 The Stoics and the practical: a Roman reply to Aristotle Robin Weiss DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Weiss, Robin, "The Stoics and the practical: a Roman reply to Aristotle" (2013). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 143. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/143 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STOICS AND THE PRACTICAL: A ROMAN REPLY TO ARISTOTLE A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2013 BY Robin Weiss Department of Philosophy College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, IL - TABLE OF CONTENTS - Introduction……………………..............................................................................................................p.i Chapter One: Practical Knowledge and its Others Technê and Natural Philosophy…………………………….....……..……………………………….....p. 1 Virtue and technical expertise conflated – subsequently distinguished in Plato – ethical knowledge contrasted with that of nature in -

Like a Pendulum in Time, the History of the Human Conception of Justice Has

Rugeles: What is Justice? Rugeles 1 What is Justice? An Investigation of Leo Strauss’s Natural Right Proposition Laura Marino Rugeles, Vancouver Island University (Editor’s note: The Agora editorial committee has awarded Laura Marino Rugeles the Kendall North Award for the best essay in the 2010 issue Agora.) of the The main concern of this essay is Leo Strauss’s presentation of the idea of justice in Natural Right and History. Although Strauss’s project appears to have the character of a historical account rather than a straightforward argumentative work about justice, it is reasonable to presume that the form of his historical reconstruction contains an argument in itself. Stewart Umphrey has said that “Strauss does not say what justice is, nor does he preach justice or cry out for spiritual renewal” (32). Instead, Strauss’s suggested argument is a “carefully considered hypothesis couched in further questions-like Socrates’ hypothesis that virtue is knowledge-and hypotheses of this kind are doctrines in a sense; they tell us where to keep looking” (Umphrey 33). I believe this claim to be fundamentally correct. In fact, Strauss’s work leaves us with projects of investigation that are pivotal to the question of justice. These projects will reveal themselves after a critical examination of Strauss’ historical account. Justice is an idea that each person can understand but hardly all can agree on. In fact, “the disagreement regarding the principles of justice... seems to reveal genuine perplexity aroused by a divination or insufficient grasp of natural right” (Strauss 100). That is indeed one of the most stubborn problems in human history. -

Passionate Platonism: Plutarch on the Positive Role of Non-Rational Affects in the Good Life

Passionate Platonism: Plutarch on the Positive Role of Non-Rational Affects in the Good Life by David Ryan Morphew A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Victor Caston, Chair Professor Sara Ahbel-Rappe Professor Richard Janko Professor Arlene Saxonhouse David Ryan Morphew [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-4773-4952 ©David Ryan Morphew 2018 DEDICATION To my wife, Renae, whom I met as I began this project, and who has supported me throughout its development. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I am grateful to my advisors and dissertation committee for their encouragement, support, challenges, and constructive feedback. I am chiefly indebted to Victor Caston for his comments on successive versions of chapters, for his great insight and foresight in guiding me in the following project, and for steering me to work on Plutarch’s Moralia in the first place. No less am I thankful for what he has taught me about being a scholar, mentor, and teacher, by his advice and especially by his example. There is not space here to express in any adequate way my gratitude also to Sara Ahbel-Rappe and Richard Janko. They have been constant sources of inspiration. I continue to be in awe of their ability to provide constructive criticism and to give incisive critiques coupled with encouragement and suggestions. I am also indebted to Arlene Saxonhouse for helping me to see the scope and import of the following thesis not only as of interest to the history of philosophy but also in teaching our students to reflect on the kind of life that we want to live.