Terahertz-Time Domain Spectrometer with 90 Db Peak Dynamic Range

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simultaneous Intensity Profiling of Multiple Laser Beams Using the Bladecam-XHR Camera

Simultaneous Intensity Profiling of Multiple Laser Beams Using the BladeCam-XHR Camera Shaun Pacheco College of Optical Sciences, University of Arizona Rongguang Liang College of Optical Sciences, University of Arizona Rocco Dragone Vice President of Engineering, DataRay, Inc. Real-Time Profiling of Multiple Laser Beams There are several applications where the parallel processing of multiple beams can significantly decrease the overall time needed for the process. Intensity profile measurements that can characterize each of those beams can lead to improvements in that application. If each beam had to be characterized individually, the process would be very time consuming, especially for large numbers of beams. This white paper describes how the BladeCam-XHR can be used to simultaneously measure the intensity profile measurements for multiple beams by measuring the diffraction pattern from a diffraction grating and the intensity profile from a 3x3 fiber array focused using a 0.5 NA objective. Diffraction Gratings Diffraction gratings are periodic optical components that diffract an incident beam into several outgoing beams. The grating profile determines both the angle of the diffracted beam modes and the efficiency of light sent into each of those modes. Grating fabrication errors or a change in the incident wavelength can significantly change the performance of a diffraction grating. The BladeCam- XHR, Figure 1, can be used to measure the point spread function (PSF) of each mode, the relative efficiency of each mode and the spacing between diffraction modes. Figure 1 BladeCam-XHR Using the BladeCam-XHR for Diffraction Grating Evaluation The profiling mode in the DataRay software can be used to evaluate the performance of a diffraction grating. -

Applications of Laser Spectroscopy Constitute a Vast Field, Which Is Difficult to Spectroscopy Cover Comprehensively in a Review

LASERS & OPTICS 151 many cases non-destructively. A variety of beam manipulation schemes are avail able for the irradiation of samples either directly or after preparation. The unique properties of laser radiation in terms of coherence, intensity and directionality permit remote chemical sensing, where the analytical equipment and the sample are separated by large distances, even of several kilometres. Absorption, and in particular differential absorption, can be utilised in long-path measurements, whereas elastic and inelastic backscatter- ing as well as fluorescence can be used for range-resolved radar-like measure ments (LIDAR: light detection and rang ing). Laser light can also be efficiently transported in optical fibres to remotely located measurement sites. Various prop erties of the fibre itself influence the laser light propagating through the fibre, thus Applications of Laser forming a basis for fibre optic sensors. Applications of laser spectroscopy constitute a vast field, which is difficult to Spectroscopy cover comprehensively in a review. Rather than attempting such a review, examples from a variety of fields are cho Costas Fotakis sen for illustrating the power of applied University of Crete, Greece laser spectroscopy. Sune Svanberg Lund Institute of Technology, Sweden Applications in Analytical Chemistry Laser spectroscopy is making a major impact in many traditional fields of ana As the new millennium approaches the Above The Italian research vessel Urania, carrying a lytical spectroscopy. For instance, opto- know how in the field of laser-matter Swedish laser radar system, which has sailed under the galvanic spectroscopy on analytical smoky plumes of Sicilian volcanos in Italy measuring the interactions has matured to the stage of sulphur dioxide content flames increases the sensitivity of enabling several exciting real life applica absorption and emission flame spec tions. -

Hair Reduction by Laser

Ames Locations To Eldora, Iowa Falls, McFarland Clinic North Ames Story City, Urgent Care Webster City Treatment McFarland Clinic (3815 Stange Rd.) Bloomington Road McFarland Clinic Physical Therapy - Somerset West Ames e. (2707 Stange Rd., Suite 102) 24th Street Av f e. Duf Av You should not use any Accutane (a prescribed oral US 69 Ontario Street 13th Street Grand 13th Street acne medication) or gold medications (for arthritis) McFarland Clinic (1215 Duff) MGMC - North Addition for six months prior to a treatment. You should William R. Bliss Cancer Center 12th Street Stange Road . e. Mary Greeley Medical Center (MGMC) McFarland Eye Center not use retinoids (e.g. Retin A, Fifferin, Differin, Av (1111 Duff Ave.) (1128 Duff) e. 11th Street Ramp Av McFarland Family Avita, Tazorac), alpha-hydroxy acid moisturizers, Medicine East Hyland St Medical Arts Building (1018 Duff) To Boone, Carroll I-35 bleaching creams (hydroquinone) or chemical peels Iowa State (1015 Duff) Jefferson N. Dakota Marshall University for two weeks prior to a treatment. Do not pluck the Lincoln Way Lincoln Way Express Care Express Care hairs, wax or use depilatories or electrolysis for six e. (3800 Lincoln Way) (640 Lincoln Way) weeks prior to a treatment. Av McFarland Clinic West Ames Hy-Vee (3600 Lincoln Way) Hy-Vee e. Av ff You may be asked to shave the area prior to your S. Dakota To Nevada, Du first treatment appointment. You may also be Marshalltown prescribed a topical anesthetic (numbing) cream to Highway 30 help reduce any discomfort the laser may cause. Blvd University First Treatment: The laser will be used to treat the N areas by your dermatologist or one of the trained Oakwood Road Airport Road dermatology staff. -

Laser Pointer Safety About Laser Pointers Laser Pointers Are Completely Safe When Properly Used As a Visual Or Instructional Aid

Harvard University Radiation Safety Services Laser Pointer Safety About Laser Pointers Laser pointers are completely safe when properly used as a visual or instructional aid. However, they can cause serious eye damage when used improperly. There have been enough documented injuries from laser pointers to trigger a warning from the Food and Drug Administration (Alerts and Safety Notifications). Before deciding to use a laser pointer, presenters are reminded to consider alternate methods of calling attention to specific items. Most presentation software packages offer screen pointer options with the same features, but without the laser hazard. Selecting a Safe Laser Pointer 1) Choose low power lasers (Class 2) Whenever possible, select a Class 2 laser pointer because of the lower risk of eye damage. 2) Choose red-orange lasers (633 to 650 nm wavelength, choose closer to 635 nm) The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) researchers found that some green laser pointers can emit harmful levels of infrared radiation. The green laser pointers create green light beam in a three step process. A standard laser diode first generates near infrared light with a wavelength of 808nm, and pumps it into a ND:YVO4 crystal that converts the 808 nm light into infrared with a wavelength of 1064 nm. The 1064 nm light passes into a frequency doubling crystal that emits green light at a wavelength of 532nm finally. In most units, a combination of coatings and filters keeps all the infrared energy confined. But the researchers found that really inexpensive green lasers can lack an infrared filter altogether. One tested unit was so flawed that it released nine times more infrared energy than green light. -

Solid State Laser

SOLID STATE LASER Edited by Amin H. Al-Khursan Solid State Laser Edited by Amin H. Al-Khursan Published by InTech Janeza Trdine 9, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia Copyright © 2012 InTech All chapters are Open Access distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. After this work has been published by InTech, authors have the right to republish it, in whole or part, in any publication of which they are the author, and to make other personal use of the work. Any republication, referencing or personal use of the work must explicitly identify the original source. As for readers, this license allows users to download, copy and build upon published chapters even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. Notice Statements and opinions expressed in the chapters are these of the individual contributors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. No responsibility is accepted for the accuracy of information contained in the published chapters. The publisher assumes no responsibility for any damage or injury to persons or property arising out of the use of any materials, instructions, methods or ideas contained in the book. Publishing Process Manager Iva Simcic Technical Editor Teodora Smiljanic Cover Designer InTech Design Team First published February, 2012 Printed in Croatia A free online edition of this book is available at www.intechopen.com Additional hard copies can be obtained from [email protected] Solid State Laser, Edited by Amin H. -

Early-Stage Dynamics of Chloride Ion–Pumping Rhodopsin Revealed by a Femtosecond X-Ray Laser

Early-stage dynamics of chloride ion–pumping rhodopsin revealed by a femtosecond X-ray laser Ji-Hye Yuna,1, Xuanxuan Lib,c,1, Jianing Yued, Jae-Hyun Parka, Zeyu Jina, Chufeng Lie, Hao Hue, Yingchen Shib,c, Suraj Pandeyf, Sergio Carbajog, Sébastien Boutetg, Mark S. Hunterg, Mengning Liangg, Raymond G. Sierrag, Thomas J. Laneg, Liang Zhoud, Uwe Weierstalle, Nadia A. Zatsepine,h, Mio Ohkii, Jeremy R. H. Tamei, Sam-Yong Parki, John C. H. Spencee, Wenkai Zhangd, Marius Schmidtf,2, Weontae Leea,2, and Haiguang Liub,d,2 aDepartment of Biochemistry, College of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Yonsei University, Seodaemun-gu, 120-749 Seoul, South Korea; bComplex Systems Division, Beijing Computational Science Research Center, Haidian, 100193 Beijing, People’s Republic of China; cDepartment of Engineering Physics, Tsinghua University, 100086 Beijing, People’s Republic of China; dDepartment of Physics, Beijing Normal University, Haidian, 100875 Beijing, People’s Republic of China; eDepartment of Physics, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287; fPhysics Department, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 53201; gLinac Coherent Light Source, Stanford Linear Accelerator Center National Accelerator Laboratory, Menlo Park, CA 94025; hDepartment of Chemistry and Physics, Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Advanced Molecular Imaging, La Trobe Institute for Molecular Science, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC 3086, Australia; and iDrug Design Laboratory, Graduate School of Medical Life Science, Yokohama City University, 230-0045 Yokohama, Japan Edited by Nicholas K. Sauter, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Axel T. Brunger February 21, 2021 (received for review September 30, 2020) Chloride ion–pumping rhodopsin (ClR) in some marine bacteria uti- an acceptor aspartate (13–15). -

Section 5: Optical Amplifiers

SECTION 5: OPTICAL AMPLIFIERS 1 OPTICAL AMPLIFIERS S In order to transmit signals over long distances (>100 km) it is necessary to compensate for attenuation losses within the fiber. S Initially this was accomplished with an optoelectronic module consisting of an optical receiver, a regeneration and equalization system, and an optical transmitter to send the data. S Although functional this arrangement is limited by the optical to electrical and electrical to optical conversions. Fiber Fiber OE OE Rx Tx Electronic Amp Optical Equalization Signal Optical Regeneration Out Signal In S Several types of optical amplifiers have since been demonstrated to replace the OE – electronic regeneration systems. S These systems eliminate the need for E-O and O-E conversions. S This is one of the main reasons for the success of today’s optical communications systems. 2 OPTICAL AMPLIFIERS The general form of an optical amplifier: PUMP Power Amplified Weak Fiber Signal Signal Fiber Optical AMP Medium Optical Signal Optical Out Signal In Some types of OAs that have been demonstrated include: S Semiconductor optical amplifiers (SOAs) S Fiber Raman and Brillouin amplifiers S Rare earth doped fiber amplifiers (erbium – EDFA 1500 nm, praseodymium – PDFA 1300 nm) The most practical optical amplifiers to date include the SOA and EDFA types. New pumping methods and materials are also improving the performance of Raman amplifiers. 3 Characteristics of SOA types: S Polarization dependent – require polarization maintaining fiber S Relatively high gain ~20 dB S Output saturation power 5-10 dBm S Large BW S Can operate at 800, 1300, and 1500 nm wavelength regions. -

Development of High-Power Optical Amplifier

Development of High-Power Optical Amplifier by Yoshio Tashiro *, Satoshi Koyanagi *2, Keiichi Aiso *3, Kanji Tanaka * and Shu Namiki * With the development of the D-WDM (Dense Wavelength Division-Multiplex) ABSTRACT transmission technology together with its practical applications in recent years, optical amplifiers --in particular EDFA (Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifier)-- used in these transmis- sion systems are required to have ever higher performance. In this report, a high-power EDFA is presented which has achieved a high signal output of 1.5 W. The EDFA uses a set of high power pumping light sources in which the outputs of semiconductor laser diodes in the 1480-nm range are multiplexed over three wavelengths. 1. INTRODUCTION lasers 5) of high-power at 1064 nm for example --which is pumped by GaAs semiconductor lasers at 800 nm-- as a With the development of the D-WDM transmission tech- pumping light source, thereby compensating for the low nology together with its practical applications in recent quantum conversion efficiency. What is more, intensive years, optical amplifiers --in particular the EDFA which is research 6) is going on to obtain higher outputs, in which finding wide applications- used in these transmission sys- high-power semiconductor lasers 4) at 980 nm in multi- tems are required to have higher power. This is because, mode are employed to pump a double-clad fiber. The fiber as the total power of optical signal increases due to the has a core co-doped with Er and Yb together with the first- increase in multiplexing signals, so does the power of the and second-clad layers, such that the first clad supports EDFA necessary to obtain the same level of optical gain. -

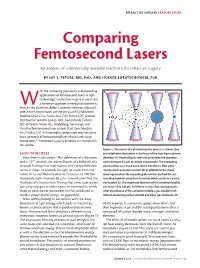

Comparing Femtosecond Lasers an Analysis of Commercially Available Platforms for Refractive Surgery

REFRACTIVE SURGERY FEATURE STORY Comparing Femtosecond Lasers An analysis of commercially available platforms for refractive surgery. BY JAY S. PEPOSE, MD, PHD, AND HOLGER LUBATSCHOWSKI, PHD ith the increasing popularity and expanding A BCD applications of femtosecond lasers in oph- thalmology,1,2 refractive surgery in particular, W a common question among practitioners is, how do the platforms differ? Currently commercially avail- able in the United States are the IntraLase FS (Advanced Medical Optics, Inc., Santa Ana, CA), Femto LDV (Ziemer Ophthalmic Systems Group, Port, Switzerland), Femtec (20/10 Perfect Vision AG, Heidelberg, Germany), and VisuMax femtosecond laser system (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA). A meaningful comparison requires some basic concepts of femtosecond laser physics and tissue interactions,3-5 important aspects of which are reviewed in this article. Figure 1. The course of a photodisruptive process is shown.Due BASIC PRINCIPLES to multiphoton absorption in the focus of the laser beam,plasma How short is ultrashort? The definition of a femtosec- develops (A).Depending on the laser parameter,the diameter ond is 10-15 seconds (ie, one millionth of a billionth of a varies between 0.5 µm to several micrometers.The expanding second). Putting that information into comprehensible plasma drives as a shock wave,which transforms after a few terms, it takes 1.2 seconds for light to travel from the microns to an acoustic transient (B).In addition to the shock moon to an earthbound observer’s retinas. In 100 fem- wave’s generation,the expanding plasma has pushed the sur- toseconds, light traverses 30 µm—around one-third the rounding medium away from its center,which results in a cavita- thickness of a human hair. -

14. Measuring Ultrashort Laser Pulses I: Autocorrelation the Dilemma the Goal: Measuring the Intensity and Phase Vs

14. Measuring Ultrashort Laser Pulses I: Autocorrelation The dilemma The goal: measuring the intensity and phase vs. time (or frequency) Why? The Spectrometer and Michelson Interferometer 1D Phase Retrieval Autocorrelation 1D Phase Retrieval E(t) Single-shot autocorrelation E(t–) The Autocorrelation and Spectrum Ambiguities Third-order Autocorrelation Interferometric Autocorrelation 1 The Dilemma In order to measure an event in time, you need a shorter one. To study this event, you need a strobe light pulse that’s shorter. Photograph taken by Harold Edgerton, MIT But then, to measure the strobe light pulse, you need a detector whose response time is even shorter. And so on… So, now, how do you measure the shortest event? 2 Ultrashort laser pulses are the shortest technological events ever created by humans. It’s routine to generate pulses shorter than 10-13 seconds in duration, and researchers have generated pulses only a few fs (10-15 s) long. Such a pulse is to one second as 5 cents is to the US national debt. Such pulses have many applications in physics, chemistry, biology, and engineering. You can measure any event—as long as you’ve got a pulse that’s shorter. So how do you measure the pulse itself? You must use the pulse to measure itself. But that isn’t good enough. It’s only as short as the pulse. It’s not shorter. Techniques based on using the pulse to measure itself are subtle. 3 Why measure an ultrashort laser pulse? To determine the temporal resolution of an experiment using it. To determine whether it can be made even shorter. -

Optically Pumped Semiconductor Lasers Power

Optically Pumped Semiconductor Lasers Power. Precision. Performance. – based on semiconductor lasers Superior Reliability & Performance History of a Breakthrough History of a Breakthrough For more than a decade, solid-state lasers have been replacing legacy gas lasers in application after application. Even solid-state lasers, with their reputation for reliability and performance, have had limitations as it relates to accessible wave- lengths and power ranges. In the late 1990’s Coherent identified the capabilities of a novel concept for a semiconductor based platform that would overcome these limitations. Investing in fundamental developments and creating an IP position, Coherent pioneered this concept and introduced the Optically Pumped Semiconductor Laser (OPSL). In 2001, the first commercial OPSL became available as a technology breakthrough. Since their beginnings, OPSLs were considered the technology of choice in a variety of applications that require true CW output – from the UV to Visible and IR. OPSL technology enables us to improve many applications that were previously limited by the fixed wavelength and power of other laser technologies. Today, with OPSL technology, you no longer have to work around the closest fit wavelength. With OPSLs, you can find the best wavelength to fit your application. OPSL Advantages and Benefits Optically Pumped Semiconductor Laser Wavelength Scalability: Responding to the need for a broad range of wavelengths in many laser applications, OPSLs with their unique wavelength flexibility, are different from any other solid-state based laser. The fundamental near-IR output wavelength is determined by the structure of the InGaAs (semiconductor) gain chip, and can be set anywhere between 920 nm and 1154 nm, yielding frequency-doubled and tripled output between 355 nm and 577 nm. -

The Effect of Long Timescale Gas Dynamics on Femtosecond Filamentation

The effect of long timescale gas dynamics on femtosecond filamentation Y.-H. Cheng, J. K. Wahlstrand, N. Jhajj, and H. M. Milchberg* Institute for Research in Electronics and Applied Physics, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA *[email protected] Abstract: Femtosecond laser pulses filamenting in various gases are shown to generate long- lived quasi-stationary cylindrical depressions or ‘holes’ in the gas density. For our experimental conditions, these holes range up to several hundred microns in diameter with gas density depressions up to ~20%. The holes decay by thermal diffusion on millisecond timescales. We show that high repetition rate filamentation and supercontinuum generation can be strongly affected by these holes, which should also affect all other experiments employing intense high repetition rate laser pulses interacting with gases. ©2013 Optical Society of America OCIS codes: (190.5530) Pulse propagation and temporal solitons; (350.6830) Thermal lensing; (320.6629) Supercontinuum generation; (260.5950) Self-focusing. References and Links 1. A. Couairon and A. Mysyrowicz, “Femtosecond filamentation in transparent media,” Phys. Rep. 441(2-4), 47– 189 (2007). 2. P. B. Corkum, C. Rolland, and T. Srinivasan-Rao, “Supercontinuum generation in gases,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 57(18), 2268–2271 (1986). S. A. Trushin, K. Kosma, W. Fuss, and W. E. Schmid, “Sub-10-fs supercontinuum radiation generated by filamentation of few-cycle 800 nm pulses in argon,” Opt. Lett. 32(16), 2432–2434 (2007). 3. N. Zhavoronkov, “Efficient spectral conversion and temporal compression of femtosecond pulses in SF6.,” Opt. Lett. 36(4), 529–531 (2011). 4. C. P. Hauri, R. B.