Disorders of the Umbilical Cord

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Embryology and Development

BIOL 6505 − INTRODUCTION TO FETAL MEDICINE 3. EMBRYOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT Arlet G. Kurkchubasche, M.D. INTRODUCTION Embryology – the field of study that pertains to the developing organism/human Basic embryology –usually taught in the chronologic sequence of events. These events are the basis for understanding the congenital anomalies that we encounter in the fetus, and help explain the relationships to other organ system concerns. Below is a synopsis of some of the critical steps in embryogenesis from the anatomic rather than molecular basis. These concepts will be more intuitive and evident in conjunction with diagrams and animated sequences. This text is a synopsis of material provided in Langman’s Medical Embryology, 9th ed. First week – ovulation to fertilization to implantation Fertilization restores 1) the diploid number of chromosomes, 2) determines the chromosomal sex and 3) initiates cleavage. Cleavage of the fertilized ovum results in mitotic divisions generating blastomeres that form a 16-cell morula. The dense morula develops a central cavity and now forms the blastocyst, which restructures into 2 components. The inner cell mass forms the embryoblast and outer cell mass the trophoblast. Consequences for fetal management: Variances in cleavage, i.e. splitting of the zygote at various stages/locations - leads to monozygotic twinning with various relationships of the fetal membranes. Cleavage at later weeks will lead to conjoined twinning. Second week: the week of twos – marked by bilaminar germ disc formation. Commences with blastocyst partially embedded in endometrial stroma Trophoblast forms – 1) cytotrophoblast – mitotic cells that coalesce to form 2) syncytiotrophoblast – erodes into maternal tissues, forms lacunae which are critical to development of the uteroplacental circulation. -

Management of Patent Vitellointestinal Duct in Infants

Published online: 2021-02-17 94 OriginalPatent Vitellointestinal Article Duct Ghritlaharey Management of Patent Vitellointestinal Duct in Infants Rajendra K. Ghritlaharey1 1Department of Paediatric Surgery, Gandhi Medical College and Address for correspondence Rajendra K. Ghritlaharey, MS, MCh, Associated Kamla Nehru and Hamidia Hospital, Bhopal, Madhya FAIS, MAMS, DLitt, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Gandhi Medical Pradesh, India College and Associated Kamla Nehru and Hamidia Hospitals, Bhopal 462001, Madhya Pradesh, India (e-mail: [email protected]). Ann Natl Acad Med Sci (India) 2021;57:94–99. Abstract Objectives This study was undertaken to investigate and review the clinical presen- tation, surgical procedures executed, and the final outcome of infants managed for the patent vitellointestinal duct. Materials and Methods This is a single-institution, retrospective study and included infants who were operated for the patent vitellointestinal duct. This study was conducted at author’s Department of Paediatric Surgery during the last 20 years; from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2019. Results A total of 24 infants were operated for the patent vitellointestinal duct during the study period and comprised 20 (83.3%) boys and 4 (16.6%) girls. The age of infants ranged from 7 days to 10 months, with a mean of 88.41 ± 64.9 days. Twenty-three (95.8%) infants were operated within 6 months of the age, 17 (70.8%) of them were operated within 3 months of the age. Only one (4.1%) infant was operated at the age of 10 months. Among 24 infants, 13 (54.1%) were presented with features suggestive of acute intestinal obstruction and remaining 11 (45.8%) were presented with fecal discharges through the umbilicus without intestinal obstruction. -

Extremely Rare Presentation of an Omphalomesenteric Cyst in a 61-Year-Old Patient

Turk J Surg 2017; 33: 43-44 Case Report DOI: 10.5152/UCD.2014.2748 Extremely rare presentation of an omphalomesenteric cyst in a 61-year-old patient Recep Aktimur1, Uğur Yaşar2, Elif Çolak1, Nuraydın Özlem1 ABSTRACT The umbilicus is remaining scar tissue from the umbilical cord in the fetus. If the omphalomesenteric duct in the umbilicus is not properly closed, an ileal-umbilical fistula, sinus formation, cysts, or, most commonly, Meckel’s di- verticulum can develop. The others are very rare and mostly occur in the pediatric population. We describe herein a 61-year-old female with a giant omphalomesenteric cyst presented as an asymptomatic infraumbilical mass. To our knowledge, this is the oldest patient reported and the largest cyst described in the literature. The diagnosis of a painless abdominal mass frequently suggests malignancy in older patients. But, extremely rare conditions can be detected, such as an omphalomesenteric cyst. Keywords: Adult, anomaly, cyst, duct, omphalomesenteric INTRODUCTION The umbilicus is remaining scar tissue from the umbilical cord in the fetus. It contains the urachus, om- phalomesenteric duct, and the round ligament’s embryonic remnants, which can be a source of many clinical problems. Also, umbilical hernia can occur in cases of closure defects of the umbilical ring. If the omphalomesenteric duct is not properly closed, an ileal-umbilical fistula, sinus formation, cysts, or Meckel’s diverticulum can develop. Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common omphalomesenteric duct anomaly, and it is also the most common congenital abnormality of the gastrointestinal tract (2%). Other anomalies associated with the omphalomesenteric duct are very rare and mostly occur in the pediatric population. -

Folding of Embryo

❑There is progressive increase in the size of the embryonic disc due to rapid growth of cells of central part of embryonic disc and rapid growth of somites. ❑ This causes conversion of flat pear-shaped germ disc into a cylindrical embryo. ❑The head and tail ends of the disc remain relatively close together.The increased length of the disc causes it to bulge upward into the amniotic cavity. ❑With the formation of the head and tail folds, parts of the yolk sac become enclosed within the embryo. ❑ In this way, a tube lined by endoderm is formed in the embryo. This is the primitive gut, from which most of the gastrointestinal tract is derived. ❑ At first, the gut is in wide communication with the yolk sac. The part of the gut cranial to this communication is called the foregut; the part caudal to the communication is called the hindgut; while the intervening part is called the midgut . ❑The communication with the yolk sac becomes progressively narrower. As a result of these changes, the yolk sac becomes small and inconspicuous, and is now termed the definitive yolk sac (also called the umbilical vesicle). ❑The narrow channel connecting it to the gut is called the vitellointestinal duct (also called vitelline duct; yolk stalk or omphalomesenteric duct). This duct becomes elongated and eventually disappears. ❑With the formation of the cavity, the embryo (along with the amniotic cavity and yolk sac) remains attached to the trophoblast only by extraembryonic mesoderm into which the coelom does not exist. This extraembryonic mesoderm forms the connecting stalk. -

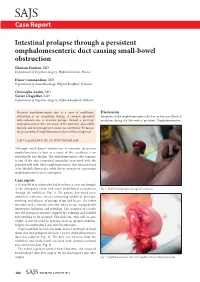

Intestinal Prolapse Through a Persistent Omphalomesenteric Duct

SAJS Case Report Intestinal prolapse through a persistent omphalomesenteric duct causing small-bowel obstruction Ghislain Pauleau, MD Department of Digestive Surgery, Hôpital Laveran, France Diane Commandeur, MD Department of Anaesthesiology, Hôpital Bouffard, Djibouti Christophe Andro, MD Xavier Chapellier, MD Department of Digestive Surgery, Hôpital Bouffard, Djibouti Persistent omphalomesenteric duct as a cause of small-bowel Discussion obstruction is an exceptional finding. A neonate presented Anomalies in the omphalomesenteric duct occur because of lack of with occlusion due to intestinal prolapse through a persistent involution during the 9th week of gestation. Omphalomesenteric omphalomesenteric duct. Remnants of the duct were successfully resected, and the postoperative course was uneventful. We discuss the presentation of omphalomesenteric duct and its management. S Afr J Surg 2012;50(3):102-103. DOI:7196/SAJS.1289 Although small-bowel obstruction is common, persistent omphalomesenteric duct as a cause of this condition is an exceptionally rare finding. The omphalomesenteric duct remnant is one of the rare congenital anomalies associated with the primitive yolk stalk. Most omphalomesenteric duct remnants tend to be Meckel’s diverticula, while the occurrence of a persistent omphalomesenteric duct is infrequent. Case report A 20-day-old male infant who had been born at term was brought to the emergency room with acute small-bowel evisceration Fig. 1. Small-bowel prolapse through the umbilicus. through the umbilicus (Fig. 1). His parents had noted peri- umbilical erythema, mucus-containing umbilical drainage, vomiting, and absence of passage of gas and faeces. The infant was taken to the intensive care unit, where he was managed with intravenous hydration and refeeding. -

Human Embryologyembryology

HUMANHUMAN EMBRYOLOGYEMBRYOLOGY Department of Histology and Embryology Jilin University ChapterChapter 22 GeneralGeneral EmbryologyEmbryology DevelopmentDevelopment inin FetalFetal PeriodPeriod 8.1 Characteristics of Fetal Period 210 days, from week 9 to delivery. characteristics: maturation of tissues and organs rapid growth of the body During 3-5 month, fetal growth in length is 5cm/M. In last 2 month, weight increases in 700g/M. relative slowdown in growth of the head compared with the rest of the body 8.2 Fetal AGE Fertilization age lasts 266 days, from the moment of fertilization to the day when the fetal is delivered. menstrual age last 280 days, from the first day of the last menstruation before pregnancy to the day when the fetal is delivered. The formula of expected date of delivery: year +1, month -3, day+7. ChapterChapter 22 GeneralGeneral EmbryologyEmbryology FetalFetal membranesmembranes andand placentaplacenta Villous chorion placenta Decidua basalis Umbilical cord Afterbirth/ secundines Fusion of amnion, smooth chorion, Fetal decidua capsularis, membrane decidua parietalis 9.1 Fetal Membranes TheThe fetalfetal membranemembrane includesincludes chorionchorion,, amnion,amnion, yolkyolk sac,sac, allantoisallantois andand umbilicalumbilical cord,cord, originatingoriginating fromfrom blastula.blastula. TheyThey havehave functionsfunctions ofof protection,protection, nutrition,nutrition, respiration,respiration, excretion,excretion, andand producingproducing hormonehormone toto maintainmaintain thethe pregnancy.pregnancy. delivery 1) Chorion: villous and smooth chorion Villus chorionic plate primary villus trophoblast secondary villus extraembryonic tertiary villus mesoderm stem villus Amnion free villus decidua parietalis Free/termin al villus Stem/ancho chorion ring villus Villous chorion Smooth chorion Amniotic cavity Extraembyonic cavity disappears gradually; Amnion is added into chorionic plate; Villous and smooth chorion is formed. -

Unit 3 Embryo Questions

Unit 3 Embryology Clinically Oriented Anatomy (COA) Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Created by Parker McCabe, Fall 2019 parker.mccabe@@uhsc.edu Solu%ons 1. B 11. A 21. D 2. C 12. B 22. D 3. C 13. E 23. D 4. B 14. D 24. A 5. E 15. C 25. D 6. C 16. B 26. B 7. D 17. E 27. C 8. B 18. A 9. C 19. C 10. D 20. B Digestive System 1. Which of the following structures develops as an outgrowth of the endodermal epithelium of the upper part of the duodenum? A. Stomach B. Pancreas C. Lung buds D. Trachea E. Esophagus Ques%on 1 A. Stomach- Foregut endoderm B. Pancreas- The pancreas, liver, and biliary apparatus all develop from outgrowths of the endodermal epithelium of the upper part of the duodenum. C. Lung buds- Foregut endoderm D. Trachea- Foregut endoderm E. Esophagus- Foregut endoderm 2. Where does the spleen originate and then end up after the rotation of abdominal organs during fetal development? A. Ventral mesentery à left side B. Ventral mesentery à right side C. Dorsal mesentery à left side D. Dorsal mesentery à right side E. It does not relocate Question 2 A. Ventral mesentery à left side B. Ventral mesentery à right side C. Dorsal mesentery à left side- The spleen and dorsal pancreas are embedded within the dorsal mesentery (greater omentum). After rotation, dorsal will go to the left side of the body and ventral will go to the right side of the body (except for the ventral pancreas). -

Ultrasound in the First Trimester

ULTRASOUND IN THE 4 FIRST TRIMESTER INTRODUCTION First trimester ultrasound is often done to assess pregnancy location and thus it overlaps between an obstetric and gynecologic ultrasound examination. Accurate performance of an ultrasound examination in the first trimester is important given its ability to confirm an intrauterine gestation, assess viability and number of embryo(s) and accurately date a pregnancy, all of which are critical for the course of pregnancy. Main objectives of the first trimester ultrasound examination are listed in Table 4.1. These objectives may differ somewhat based upon the gestational age within the first trimester window, be it 6 weeks, 9 weeks, or 12 weeks, but the main goals are identical. In this chapter, the approach to the first trimester ultrasound examination will be first discussed followed by the indications to the ultrasound examination in early gestation. Chronologic sequence of the landmarks of the first trimester ultrasound in the normal pregnancy will be described and ultrasound findings of pregnancy failure will be presented. The chapter will also display some of the major fetal anomalies that can be recognized by ultrasound in the first trimester. Furthermore, given the importance of first trimester assignment of chorionicity in multiple pregnancies, this topic will also be addressed in this chapter. TABLE 4.1 Main Objectives of Ultrasound Examination in the First Trimester - Confirmation of pregnancy - Intrauterine localization of gestational sac - Confirmation of viability (cardiac activity in embryo/fetus) - Detection of signs of early pregnancy failure - Single vs. Multiple pregnancy (define chorionicity in multiples) - Assessment of gestational age (pregnancy dating) - Assessment of normal embryo and gestational sac before 10 weeks - Assessment of basic anatomy after 11 week TRANSVAGINAL ULTRASOUND EXAMINATION IN THE FIRST TRIMESTER There is general consensus that, with rare exceptions, ultrasound examination in the first trimester of pregnancy should be performed transvaginally. -

General Embryology-3-Placenta.Pdf

Derivatives of Germ Layers ECTODREM 1. Lining Epithelia of i. Skin ii. Lips, cheeks, gums, part of floor of mouth iii. Parts of palate, nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses iv. Lower part of anal canal v. Terminal part of male urethera vi. Labia majora and outer surface of labia minora vii. Epithelium of cornea, conjuctiva, ciliary body, iris viii. Outer layer of tympanic membrane and membranous labyrinth ECTODERM (contd.): 2. Glands – Exocrine – Sweet glands, sebaceous glands Parotid, Mammary and lacrimal 3. Other derivatives i. Hair ii. Nails iii. Enamel of teeth iv. Lens of eye; musculature of iris v. Nervous system MESODERM: • All connective tissue including loose areolar tissue, superficial and deep fascia, ligaments, tendons, aponeuroses and the dermis of the skin. • Specialised connective tissue like adipose tissue, reticular tissue, cartilage and bone • All muscles – smooth, striated and cardiac – except the musculature of iris. • Heart, all blood vessels and lymphatics, blood cells. • Kidneys, ureters, trigone of bladder, parts of male and female urethera, inner prostatic glands. • Ovary, uterus, uterine tubes, upper part of vagina. • Testis, epidydimis, ductus deferens, seminal vesicle ejaculatory duct. • Lining mesothelium of pleural, pericardial and peritoneal cavities; and of tunica vaginalis. • Living mesothelium of bursae and joints. • Substance of cornea, sclera, choroid, ciliary body and iris. ENDODERM: 1. Lining Epithelia of i. Part of mouth, palate, tongue, tonsil, pharynx. ii. Oesophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, anal canal (upper part) iii. Pharyngo – tympanic tube, middle ear, inner layer of tympanic membrane, mastoid antrum, air cells. iv. Respiratory tract v. Gall bladder, extrahepatic duct system, pancreatic ducts vi. -

Meckel's Diverticulitis Causing Small Bowel Obstruction by a Novel

Clinics and Practice 2011; volume 1:e51 Meckel’s diverticulitis causing 92.8% neutrophils), raised serum amylase (468 U/L) and raised urinary amylase (769 Correspondence: Vishalkumar Shelat, small bowel obstruction by a U/L). Serum lipase, electrolytes, creatinine Department of General Surgery, Tan Tock Seng novel mechanism and liver function tests were unremarkable. Hospital, 11 Jalan Tan Tock Seng, Singapore Chest and abdominal films were unremark - 308433, Singapore. E-mail: [email protected] Vishalkumar G. Shelat, Kaiwen Kelvin Li, able. The patient underwent computed tomog - Anil Rao, Tay Sze Guan raphy (CT) scan of her abdomen/pelvis on the Key words: Meckel’s diverticulum; Meckel’s diver - first day of admission which showed mild Department of General Surgery, Tan Tock ticulitis; small bowel obstruction. dilatation of the small bowels, particularly in Seng Hospital, Singapore, Singapore the distal jejunum and proximal ileum with Received for publication: 4 May 2011. thickening of the bowel wall and submucosal Accepted for publication: 21 June 2011. oedema. No transition point was seen on the CT scan (Figure 1). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Abstract Attribution NonCommercial 3.0 License (CC BY- She received symptomatic treatment. NC 3.0). However, her abdomen became increasingly Meckel’s diverticulum occurs in 2% of the distended and she developed vomiting over ©Copyright V.G. Shelat et al., 2011 general population and majority of patients next three days. A repeat CT scan of the Licensee PAGEPress, Italy remain asymptomatic. Gastrointestinal bleed - abdomen/pelvis was performed on the fourth Clinics and Practice 2011; 1:e51 ing is the most common presentation in the day of admission and this showed interval doi:10.4081/cp.2011.e51 paediatric population. -

Ultrasound Imaging of Early Extraembryonic Structures 1Sándor Nagy, 2Zoltán Papp

DSJUOG Ultrasound Imaging10.5005/jp-journals-10009-1500 of Early Extraembryonic Structures REVIEW ARTICLE Ultrasound Imaging of Early Extraembryonic Structures 1Sándor Nagy, 2Zoltán Papp ABSTRACT to arrive at an accurate diagnosis and appropriate dis- Transvaginal sonography is the most useful diagnostic method position, thus providing efficient care that benefits both to visualize the early pregnancy, to determine whether it is intra- patients and doctors. The specific sonographic appear- uterine or extrauterine (ectopic), viable or not. Detailed examina- ance of normal pregnancy depends upon the gestational tion of extraembryonic structures allows us to differentiate the age. As the gestational age increases, the ability to assess types of early pregnancy failures and highlights the backgrounds the location and normal development of the pregnancy of vaginal bleeding, as the most frequent symptom of the first trimester of gestation. The reliable ultrasonographic sign of an becomes better. intrauterine pregnancy is visualization of double decidual ring, Spontaneous abortion is one of the most common which represents the trophoblast’s layer. The abnormality in the complications of pregnancy; every 12 to 15 out of 100 sonographic appearance of a gestational sac, a yolk sac, and conceptus are miscarried in the first half of gestation. a chorionic plate can predict subsequent embryonic damage and death. Vaginal bleeding is one of the most serious symptoms of the spontaneous abortion, which the pregnant are afraid Keywords: Blighted ovum, Chorionic plate, Extraembryonic structures, Gestational sac, Missed abortion, Subchorionic of, especially when extrachorial bleeding is detected by hemorrhage, Yolk sac. ultrasound. Transvaginal sonography is the optimal way to image How to cite this article: Nagy S, Papp Z. -

Persistent Omphalomesenteric Duct

Turkish Journal of Trauma & Emergency Surgery Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2012;18 (5):446-448 Case Report Olgu Sunumu doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2012.77609 A rare cause of small bowel obstruction in adults: persistent omphalomesenteric duct Erişkinlerde ince bağırsak tıkanıklığının nadir bir nedeni: Persistan omfalomezenterik kanal Ali GÜNER, Can KEÇE, Aydın BOZ, İzzettin KAHRAMAN, Erhan REİS Previous abdominal surgery is the most common cause of Mekanik ince bağırsak tıkanıklığının en sık nedeni önceden mechanical small bowel obstruction. However, in patients yapılmış karın ameliyatlarıdır. Buna karşın, karın ameliyatı with no abdominal surgery history, it is difficult to diagnose hikayesi olmayan hastalarda tanı koyulması ve tedavi zor- and treat. Omphalomesenteric duct is a primitive embry- dur. Omfalomezenterik kanal fetal gelişim sırasında midgut onic structure of fetal development between the midgut and ile yolk kesesi arasında yer alan embriyonik bir yapıdır. Bazı yolk sac. In some cases, it may persist and result in several kişilerde, varlığı sebat eder ve özellikle çocukluk yaşlarında complications, particularly in childhood. In adults, intesti- bazı komplikasyonlara neden olur. Erişkinlerde ise omfalo- nal obstruction due to persistent omphalomesenteric duct mesenterik kanalın sebat etmesine bağlı gelişen bağırsak tı- is an extremely rare circumstance. We report a 42-year-old kanıklığı oldukça nadir rastlanılan bir durumdur. Bu yazıda, male patient presenting with omphalomesenteric duct rem- omfalomezenterik kanal açıklığının devam