Vitelline-Duct Remains at the Navel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Embryology and Development

BIOL 6505 − INTRODUCTION TO FETAL MEDICINE 3. EMBRYOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT Arlet G. Kurkchubasche, M.D. INTRODUCTION Embryology – the field of study that pertains to the developing organism/human Basic embryology –usually taught in the chronologic sequence of events. These events are the basis for understanding the congenital anomalies that we encounter in the fetus, and help explain the relationships to other organ system concerns. Below is a synopsis of some of the critical steps in embryogenesis from the anatomic rather than molecular basis. These concepts will be more intuitive and evident in conjunction with diagrams and animated sequences. This text is a synopsis of material provided in Langman’s Medical Embryology, 9th ed. First week – ovulation to fertilization to implantation Fertilization restores 1) the diploid number of chromosomes, 2) determines the chromosomal sex and 3) initiates cleavage. Cleavage of the fertilized ovum results in mitotic divisions generating blastomeres that form a 16-cell morula. The dense morula develops a central cavity and now forms the blastocyst, which restructures into 2 components. The inner cell mass forms the embryoblast and outer cell mass the trophoblast. Consequences for fetal management: Variances in cleavage, i.e. splitting of the zygote at various stages/locations - leads to monozygotic twinning with various relationships of the fetal membranes. Cleavage at later weeks will lead to conjoined twinning. Second week: the week of twos – marked by bilaminar germ disc formation. Commences with blastocyst partially embedded in endometrial stroma Trophoblast forms – 1) cytotrophoblast – mitotic cells that coalesce to form 2) syncytiotrophoblast – erodes into maternal tissues, forms lacunae which are critical to development of the uteroplacental circulation. -

Management of Patent Vitellointestinal Duct in Infants

Published online: 2021-02-17 94 OriginalPatent Vitellointestinal Article Duct Ghritlaharey Management of Patent Vitellointestinal Duct in Infants Rajendra K. Ghritlaharey1 1Department of Paediatric Surgery, Gandhi Medical College and Address for correspondence Rajendra K. Ghritlaharey, MS, MCh, Associated Kamla Nehru and Hamidia Hospital, Bhopal, Madhya FAIS, MAMS, DLitt, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Gandhi Medical Pradesh, India College and Associated Kamla Nehru and Hamidia Hospitals, Bhopal 462001, Madhya Pradesh, India (e-mail: [email protected]). Ann Natl Acad Med Sci (India) 2021;57:94–99. Abstract Objectives This study was undertaken to investigate and review the clinical presen- tation, surgical procedures executed, and the final outcome of infants managed for the patent vitellointestinal duct. Materials and Methods This is a single-institution, retrospective study and included infants who were operated for the patent vitellointestinal duct. This study was conducted at author’s Department of Paediatric Surgery during the last 20 years; from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2019. Results A total of 24 infants were operated for the patent vitellointestinal duct during the study period and comprised 20 (83.3%) boys and 4 (16.6%) girls. The age of infants ranged from 7 days to 10 months, with a mean of 88.41 ± 64.9 days. Twenty-three (95.8%) infants were operated within 6 months of the age, 17 (70.8%) of them were operated within 3 months of the age. Only one (4.1%) infant was operated at the age of 10 months. Among 24 infants, 13 (54.1%) were presented with features suggestive of acute intestinal obstruction and remaining 11 (45.8%) were presented with fecal discharges through the umbilicus without intestinal obstruction. -

Extremely Rare Presentation of an Omphalomesenteric Cyst in a 61-Year-Old Patient

Turk J Surg 2017; 33: 43-44 Case Report DOI: 10.5152/UCD.2014.2748 Extremely rare presentation of an omphalomesenteric cyst in a 61-year-old patient Recep Aktimur1, Uğur Yaşar2, Elif Çolak1, Nuraydın Özlem1 ABSTRACT The umbilicus is remaining scar tissue from the umbilical cord in the fetus. If the omphalomesenteric duct in the umbilicus is not properly closed, an ileal-umbilical fistula, sinus formation, cysts, or, most commonly, Meckel’s di- verticulum can develop. The others are very rare and mostly occur in the pediatric population. We describe herein a 61-year-old female with a giant omphalomesenteric cyst presented as an asymptomatic infraumbilical mass. To our knowledge, this is the oldest patient reported and the largest cyst described in the literature. The diagnosis of a painless abdominal mass frequently suggests malignancy in older patients. But, extremely rare conditions can be detected, such as an omphalomesenteric cyst. Keywords: Adult, anomaly, cyst, duct, omphalomesenteric INTRODUCTION The umbilicus is remaining scar tissue from the umbilical cord in the fetus. It contains the urachus, om- phalomesenteric duct, and the round ligament’s embryonic remnants, which can be a source of many clinical problems. Also, umbilical hernia can occur in cases of closure defects of the umbilical ring. If the omphalomesenteric duct is not properly closed, an ileal-umbilical fistula, sinus formation, cysts, or Meckel’s diverticulum can develop. Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common omphalomesenteric duct anomaly, and it is also the most common congenital abnormality of the gastrointestinal tract (2%). Other anomalies associated with the omphalomesenteric duct are very rare and mostly occur in the pediatric population. -

Folding of Embryo

❑There is progressive increase in the size of the embryonic disc due to rapid growth of cells of central part of embryonic disc and rapid growth of somites. ❑ This causes conversion of flat pear-shaped germ disc into a cylindrical embryo. ❑The head and tail ends of the disc remain relatively close together.The increased length of the disc causes it to bulge upward into the amniotic cavity. ❑With the formation of the head and tail folds, parts of the yolk sac become enclosed within the embryo. ❑ In this way, a tube lined by endoderm is formed in the embryo. This is the primitive gut, from which most of the gastrointestinal tract is derived. ❑ At first, the gut is in wide communication with the yolk sac. The part of the gut cranial to this communication is called the foregut; the part caudal to the communication is called the hindgut; while the intervening part is called the midgut . ❑The communication with the yolk sac becomes progressively narrower. As a result of these changes, the yolk sac becomes small and inconspicuous, and is now termed the definitive yolk sac (also called the umbilical vesicle). ❑The narrow channel connecting it to the gut is called the vitellointestinal duct (also called vitelline duct; yolk stalk or omphalomesenteric duct). This duct becomes elongated and eventually disappears. ❑With the formation of the cavity, the embryo (along with the amniotic cavity and yolk sac) remains attached to the trophoblast only by extraembryonic mesoderm into which the coelom does not exist. This extraembryonic mesoderm forms the connecting stalk. -

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS Abbreviations: • A. Arabic • abb. = abbreviation • c. circa = about • F. French • adj. adjective • G. Greek • Ge. German • cf. compare • L. Latin • dim. = diminutive • OF. Old French • ( ) plural form in brackets A-band abb. of anisotropic band G. anisos = unequal + tropos = turning; meaning having not equal properties in every direction; transverse bands in living skeletal muscle which rotate the plane of polarised light, cf. I-band. Abbé, Ernst. 1840-1905. German physicist; mathematical analysis of optics as a basis for constructing better microscopes; devised oil immersion lens; Abbé condenser. absorption L. absorbere = to suck up. acervulus L. = sand, gritty; brain sand (cf. psammoma body). acetylcholine an ester of choline found in many tissue, synapses & neuromuscular junctions, where it is a neural transmitter. acetylcholinesterase enzyme at motor end-plate responsible for rapid destruction of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. acidophilic adj. L. acidus = sour + G. philein = to love; affinity for an acidic dye, such as eosin staining cytoplasmic proteins. acinus (-i) L. = a juicy berry, a grape; applied to small, rounded terminal secretory units of compound exocrine glands that have a small lumen (adj. acinar). acrosome G. akron = extremity + soma = body; head of spermatozoon. actin polymer protein filament found in the intracellular cytoskeleton, particularly in the thin (I-) bands of striated muscle. adenohypophysis G. ade = an acorn + hypophyses = an undergrowth; anterior lobe of hypophysis (cf. pituitary). adenoid G. " + -oeides = in form of; in the form of a gland, glandular; the pharyngeal tonsil. adipocyte L. adeps = fat (of an animal) + G. kytos = a container; cells responsible for storage and metabolism of lipids, found in white fat and brown fat. -

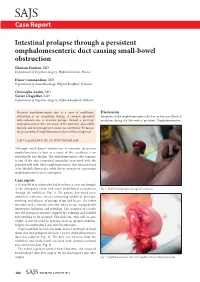

Intestinal Prolapse Through a Persistent Omphalomesenteric Duct

SAJS Case Report Intestinal prolapse through a persistent omphalomesenteric duct causing small-bowel obstruction Ghislain Pauleau, MD Department of Digestive Surgery, Hôpital Laveran, France Diane Commandeur, MD Department of Anaesthesiology, Hôpital Bouffard, Djibouti Christophe Andro, MD Xavier Chapellier, MD Department of Digestive Surgery, Hôpital Bouffard, Djibouti Persistent omphalomesenteric duct as a cause of small-bowel Discussion obstruction is an exceptional finding. A neonate presented Anomalies in the omphalomesenteric duct occur because of lack of with occlusion due to intestinal prolapse through a persistent involution during the 9th week of gestation. Omphalomesenteric omphalomesenteric duct. Remnants of the duct were successfully resected, and the postoperative course was uneventful. We discuss the presentation of omphalomesenteric duct and its management. S Afr J Surg 2012;50(3):102-103. DOI:7196/SAJS.1289 Although small-bowel obstruction is common, persistent omphalomesenteric duct as a cause of this condition is an exceptionally rare finding. The omphalomesenteric duct remnant is one of the rare congenital anomalies associated with the primitive yolk stalk. Most omphalomesenteric duct remnants tend to be Meckel’s diverticula, while the occurrence of a persistent omphalomesenteric duct is infrequent. Case report A 20-day-old male infant who had been born at term was brought to the emergency room with acute small-bowel evisceration Fig. 1. Small-bowel prolapse through the umbilicus. through the umbilicus (Fig. 1). His parents had noted peri- umbilical erythema, mucus-containing umbilical drainage, vomiting, and absence of passage of gas and faeces. The infant was taken to the intensive care unit, where he was managed with intravenous hydration and refeeding. -

Unit #2 - Abdomen, Pelvis and Perineum

UNIT #2 - ABDOMEN, PELVIS AND PERINEUM 1 UNIT #2 - ABDOMEN, PELVIS AND PERINEUM Reading Gray’s Anatomy for Students (GAFS), Chapters 4-5 Gray’s Dissection Guide for Human Anatomy (GDGHA), Labs 10-17 Unit #2- Abdomen, Pelvis, and Perineum G08- Overview of the Abdomen and Anterior Abdominal Wall (Dr. Albertine) G09A- Peritoneum, GI System Overview and Foregut (Dr. Albertine) G09B- Arteries, Veins, and Lymphatics of the GI System (Dr. Albertine) G10A- Midgut and Hindgut (Dr. Albertine) G10B- Innervation of the GI Tract and Osteology of the Pelvis (Dr. Albertine) G11- Posterior Abdominal Wall (Dr. Albertine) G12- Gluteal Region, Perineum Related to the Ischioanal Fossa (Dr. Albertine) G13- Urogenital Triangle (Dr. Albertine) G14A- Female Reproductive System (Dr. Albertine) G14B- Male Reproductive System (Dr. Albertine) 2 G08: Overview of the Abdomen and Anterior Abdominal Wall (Dr. Albertine) At the end of this lecture, students should be able to master the following: 1) Overview a) Identify the functions of the anterior abdominal wall b) Describe the boundaries of the anterior abdominal wall 2) Surface Anatomy a) Locate and describe the following surface landmarks: xiphoid process, costal margin, 9th costal cartilage, iliac crest, pubic tubercle, umbilicus 3 3) Planes and Divisions a) Identify and describe the following planes of the abdomen: transpyloric, transumbilical, subcostal, transtu- bercular, and midclavicular b) Describe the 9 zones created by the subcostal, transtubercular, and midclavicular planes c) Describe the 4 quadrants created -

Infective Endocarditis After Body Art: a Review of the Literature and Concerns Myrna L

JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT HEALTH ELSEVIER Journal of Adolescent Health 43 (2008) 217-225 Review article Infective Endocarditis After Body Art: A Review of the Literature and Concerns Myrna L. Armstrong, Ed.D., RN, FAANa·*, Scott DeBoer R.N., M.S.N., CEN, CCRN, CFRNb and Frank Cetta, M.D., FACCc aschool of Nursing , Texas Tech University H ealth Sciences Center at Hig hlpnd Lak es, Marble Fall s, Texas bUniversity of Chicago Hospitals , Peds-R-Us Medical Education, Dye r, Indiana cDivision of Pediatri c Cardiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota Manuscript received October 10, 2007 ; manuscript accepted February 9, 2008 Abstract Purpose:_ Infective endocarditis (IE) is a rare but dangerous complication of tattooing and body piercing in adolescents and young adults 15-30 years of age, with and without congenital heart disease (CHD). Because body art, including tattooing and piercing, is increasing and IE cases continue to be reported in the literature, a longitudinal assessment of IE and body art cases is important to examine for trends . Methods: A 22-year (1985-2007) longitudinal electronic MedUne and Scopus review of all published cases of IE and body art was conducted . Results: In all, 22 specific cases ofiE spanning 1991-2007 have been reported that were associated with piercing the tongue (seven), ear lobes (six), navel (five), lip (one), nose (one), and nipple (one), and reported in one heavily tattooed person; other general IE cases have also been mentioned . Twelve cases were in females , and one patient died; nine of these individuals had CHD. Twenty-one cases have been published in the 10 years from 1997-2007. -

Human Embryologyembryology

HUMANHUMAN EMBRYOLOGYEMBRYOLOGY Department of Histology and Embryology Jilin University ChapterChapter 22 GeneralGeneral EmbryologyEmbryology DevelopmentDevelopment inin FetalFetal PeriodPeriod 8.1 Characteristics of Fetal Period 210 days, from week 9 to delivery. characteristics: maturation of tissues and organs rapid growth of the body During 3-5 month, fetal growth in length is 5cm/M. In last 2 month, weight increases in 700g/M. relative slowdown in growth of the head compared with the rest of the body 8.2 Fetal AGE Fertilization age lasts 266 days, from the moment of fertilization to the day when the fetal is delivered. menstrual age last 280 days, from the first day of the last menstruation before pregnancy to the day when the fetal is delivered. The formula of expected date of delivery: year +1, month -3, day+7. ChapterChapter 22 GeneralGeneral EmbryologyEmbryology FetalFetal membranesmembranes andand placentaplacenta Villous chorion placenta Decidua basalis Umbilical cord Afterbirth/ secundines Fusion of amnion, smooth chorion, Fetal decidua capsularis, membrane decidua parietalis 9.1 Fetal Membranes TheThe fetalfetal membranemembrane includesincludes chorionchorion,, amnion,amnion, yolkyolk sac,sac, allantoisallantois andand umbilicalumbilical cord,cord, originatingoriginating fromfrom blastula.blastula. TheyThey havehave functionsfunctions ofof protection,protection, nutrition,nutrition, respiration,respiration, excretion,excretion, andand producingproducing hormonehormone toto maintainmaintain thethe pregnancy.pregnancy. delivery 1) Chorion: villous and smooth chorion Villus chorionic plate primary villus trophoblast secondary villus extraembryonic tertiary villus mesoderm stem villus Amnion free villus decidua parietalis Free/termin al villus Stem/ancho chorion ring villus Villous chorion Smooth chorion Amniotic cavity Extraembyonic cavity disappears gradually; Amnion is added into chorionic plate; Villous and smooth chorion is formed. -

•Scarless Reverse Umbilicoplasty•: a New Technique of Umbilical

Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery (2019) 72, 656–661 ‘Scarless reverse umbilicoplasty’: A new technique of umbilical transposition in abdominoplasty ∗ A. Reho , F. Randisi, A. Ferrario, D. Taibi, F. Russo, L. De Santo, G. Stefanizzi Plastic Surgery and Post Bariatric Surgery Unit, Gruppo San Donato, IC S. Ambrogio, via Faravelli 16, Milano and Policlinico San Pietro, via Forlanini 15, Ponte San Pietro, Bergamo, Italy Received 6 July 2018; accepted 18 January 2019 KEYWORDS Summary Introduction: The navel plays a major role in the aesthetics of the abdomen. A Umbilicoplasty; navel that is abnormally shaped, malpositioned or has evident scarring may compromise the Navel; outcome of an otherwise well-executed full abdominoplasty. The aim of the technique in ques- Abdominoplasty; tion is to recreate a navel that looks natural, with no visible scar, and that is properly posi- Umbilical transposition tioned. Materials and methods: The technique was performed in 147 abdominoplasties of patients of both sexes (123 females and 24 males), with an average age of 35 years and a mean BMI of 24 kg/m 2 . The procedure involves the creation of a navel of reduced size, 10 × 5 mm, and its inset in the abdominal wall. Subsequently, the as-yet-not sutured abdominal flap is extended caudally to determine the point of projection of the navel. The abdominal skin is marked, the flap is reversed and an internal suture is carried out. Results: The appearance of the navel is aesthetically pleasant and natural looking and with no visible scarring. In addition, the position of the umbilicus is always correct. -

Some Practical Facts About Displacement of the Womb, with Suggestions for Treatment

SOME PRACTICAL FACTS ABOUT displacement «r u.. y/yomb. WITH SUGGESTIONS FOR TREATMENT. PRESENTED, WITH THE COMPLIMENTS OF THE dr. McIntosh natural uterine supporter co., 192 Jackson Street, CHICAGO. INTRODUCTION. This pamphlet is intended to present briefly a view of the various (displacements of the Womb, and illustrate the striking adaptability of the (Natural Uterine Supporter to such dis- locations. The well informed physician will recognize the cuts and many ofthe facts as taken from standard works on (diseases of Women. The endeavor of the writer has been simply to present some practicalfacts on the subject, and illustrate the great value of our Supporter. It is a plain, matter-of-fact essay, without any attempt at fulsome laudation, and merits a careful and thoughtful perusal. The natural sympathies of every noble mind go out toward suffering -humanity, and the charity that “ thinketh no evil will hail anything that promises relief, as this Supporter has in hun- dreds of cases. The fact that thousands of these instruments are in use ought to be suffi- cient testimony of their value, and still a can- did, skillful trial is earnestly solicted. Yours very respectfully, Dr. McIntosh’s Natural Uterine Supporter Co. CAUTJON.—We call particular attention of Physicians to the fact that unscrupulous parties are manufacturing a worthless imi- tation of the McINTOSH natural uterine supporter, and some dishonest dealers, [for the sake of gain] are trying to sell them, knowing they are deceiving both Physician and patient. Persons Receiving a Supporter. will find, if it is genuine, the directions pasted in the cover of the box, with the head-line “DR. -

Unit 3 Embryo Questions

Unit 3 Embryology Clinically Oriented Anatomy (COA) Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Created by Parker McCabe, Fall 2019 parker.mccabe@@uhsc.edu Solu%ons 1. B 11. A 21. D 2. C 12. B 22. D 3. C 13. E 23. D 4. B 14. D 24. A 5. E 15. C 25. D 6. C 16. B 26. B 7. D 17. E 27. C 8. B 18. A 9. C 19. C 10. D 20. B Digestive System 1. Which of the following structures develops as an outgrowth of the endodermal epithelium of the upper part of the duodenum? A. Stomach B. Pancreas C. Lung buds D. Trachea E. Esophagus Ques%on 1 A. Stomach- Foregut endoderm B. Pancreas- The pancreas, liver, and biliary apparatus all develop from outgrowths of the endodermal epithelium of the upper part of the duodenum. C. Lung buds- Foregut endoderm D. Trachea- Foregut endoderm E. Esophagus- Foregut endoderm 2. Where does the spleen originate and then end up after the rotation of abdominal organs during fetal development? A. Ventral mesentery à left side B. Ventral mesentery à right side C. Dorsal mesentery à left side D. Dorsal mesentery à right side E. It does not relocate Question 2 A. Ventral mesentery à left side B. Ventral mesentery à right side C. Dorsal mesentery à left side- The spleen and dorsal pancreas are embedded within the dorsal mesentery (greater omentum). After rotation, dorsal will go to the left side of the body and ventral will go to the right side of the body (except for the ventral pancreas).