Richard J. Meadows Major, US Army (Retired) “Quiet Professional”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

Hearing on the Filipino Veterans Equity Act of 2007

S. HRG. 110–70 HEARING ON THE FILIPINO VETERANS EQUITY ACT OF 2007 HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 11, 2007 Printed for the use of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35-645 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:59 Jun 25, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\RD41451\DOCS\35645.TXT SENVETS PsN: ROWENA COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho, Ranking Member PATTY MURRAY, Washington ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania BARACK OBAMA, Illinois RICHARD M. BURR, North Carolina BERNARD SANDERS, (I) Vermont JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia SHERROD BROWN, Ohio LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina JIM WEBB, Virginia KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JON TESTER, Montana JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada WILLIAM E. BREW, Staff Director LUPE WISSEL, Republican Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:59 Jun 25, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 H:\RD41451\DOCS\35645.TXT SENVETS PsN: ROWENA CONTENTS APRIL 11, 2007 SENATORS Page Akaka, Hon. Daniel K., Chairman, U.S. Senator from Hawaii ........................... 1 Prepared statement .......................................................................................... 5 Inouye, Hon. Daniel K., U.S. Senator from Hawaii ............................................. -

March 2021 Sentinel

Sentinel NEWSLETTER OF THE QUIET PROFESSIONALS SPECIAL FORCES ASSOCIATION CHAPTER 78 The LTC Frank J. Dallas Chapter VOLUME 12, ISSUE 3 • MARCH 2021 OPERATION GENIE UFOs — The Facts Graduation Special Forces Qualification Students Graduate Course, Don Green Berets Co A/5/19th SFG Reflagging Ceremony From the Editor VOLUME 12, ISSUE 3 • MARCH 2021 In last month’s issue we highlighted a fellow IN THIS ISSUE: paratrooper who, among other things, on 6 President’s Page .............................................................. 1 January, 2021 taunted part of the attacking mob and led them away from the Senate Operation Genie .............................................................. 2 US ARMY SPECIAL chambers. The Senate voted to award Eugene OPS COMMAND Book Review: Shadow Commander: The Epic Story of Goodman the Congressional Gold Medal by Donald D. Blackburn— Guerrilla Leader and unanimous consent. Special Forces Hero by Mike Guardia ............................. 4 Kenn Miller writes that while Special Forces US Army History: The Story of Sergeant John Clem, How Miller exploits are often seen to be stealthy or US ARMY JFK SWCS The Boy Soldier ............................................................... 5 Sentinel Editor kinetic, there is another part of the mission that is largely overlooked. Going back to the UFOs — The Facts ....................................................................6 OSS in World War II, PSYOPS has always been an integral part of Graduation: Special Forces Qualification Students the mission. My A team in Vietnam, for example, had a third officer, Graduate Course, Don Green Berets ........................... 12 a 2LT, who was assigned to PSYOPS. 1ST SF COMMAND Chapter 78 February Meeting — MAJ (R) Raymond P. Ambrozak was such a standout in the field Co A/5/19th SFG Reflagging Ceremony ....................... -

FOIA) Document Clearinghouse in the World

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com Received Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Final Disposition Request Description Mode Date 17-F-0001 Greenewald, John The Black Vault PAL 10/3/2016 11/4/2016 Granted/Denied in Part I respectfully request a copy of records, electronic or otherwise, of all contracts past and present, that the DOD / OSD / JS has had with the British PR firm Bell Pottinger. Bell Pottinger Private (legally BPP Communications Ltd.; informally Bell Pottinger) is a British multinational public relations and marketing company headquartered in London, United Kingdom. 17-F-0002 Palma, Bethania - PAL 10/3/2016 11/4/2016 Other Reasons - No Records Contracts with Bell Pottinger for information operations and psychological operations. (Date Range for Record Search: From 01/01/2007 To 12/31/2011) 17-F-0003 Greenewald, John The Black Vault Mail 10/3/2016 1/13/2017 Other Reasons - Not a proper FOIA I respectfully request a copy of the Intellipedia category index page for the following category: request for some other reason Nuclear Weapons Glossary 17-F-0004 Jackson, Brian - Mail 10/3/2016 - - I request a copy of any available documents related to Army Intelligence's participation in an FBI counterintelligence source operation beginning in about 1959, per David Wise book, "Cassidy's Run," under the following code names: ZYRKSEEZ SHOCKER I am also interested in obtaining Army Intelligence documents authorizing, as well as policy documents guiding, the use of an Army source in an FBI operation. -

Air and Space Power Journal: Winter 2009

SPINE AIR & SP A CE Winter 2009 Volume XXIII, No. 4 P OWER JOURN Directed Energy A Look to the Future Maj Gen David Scott, USAF Col David Robie, USAF A L , W Hybrid Warfare inter 2009 Something Old, Not Something New Hon. Robert Wilkie Preparing for Irregular Warfare The Future Ain’t What It Used to Be Col John D. Jogerst, USAF, Retired Achieving Balance Energy, Effectiveness, and Efficiency Col John B. Wissler, USAF US Nuclear Deterrence An Opportunity for President Obama to Lead by Example Group Capt Tim D. Q. Below, Royal Air Force 2009-4 Outside Cover.indd 1 10/27/09 8:54:50 AM SPINE Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Norton A. Schwartz Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Stephen R. Lorenz Commander, Air University Lt Gen Allen G. Peck http://www.af.mil Director, Air Force Research Institute Gen John A. Shaud, USAF, Retired Chief, Professional Journals Maj Darren K. Stanford Deputy Chief, Professional Journals Capt Lori Katowich Professional Staff http://www.aetc.randolph.af.mil Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Darlene H. Barnes, Editorial Assistant Steven C. Garst, Director of Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Ann Bailey, Prepress Production Manager The Air and Space Power Journal (ISSN 1554-2505), Air Force Recurring Publication 10-1, published quarterly, is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the http://www.au.af.mil presentation and stimulation of innovative thinking on military doctrine, strategy, force structure, readiness, and other matters of national defense. -

Yanks Among the Pinoys Preface

Yanks Among the Pinoys Preface: No narrative of the Philippines would be complete without considering the outsize influence of various Americans who left an indelible mark on the country before and after independence in 1946. (The Philippines celebrates June 12, 1898 as its Independence Day but that is another story.) Except for one or two, these men - there is only one woman - are unknown among contemporary Filipinos. I have skipped more well known Americans such as William Howard Taft , Douglas MacArthur or Dwight Eisenhower. They all had a sojourn in the Philippines. I omitted the names of several American Army officers who refused to surrender to the Japanese after the fall of Bataan and Corregidor in April and May of 1942. These officers formed large Filipino guerrilla armies which tied up the occupying forces in knots. Among them were Donald Blackburn, Wendell Fertig and Russell Volckman. They have been given enough credit in books and even movies. The motivations of these Americans to stay in the country are probably as diverse as their personalities. Only Fr. James Reuter probably had a clear vision on why he came in the first place. A priest belonging to the Society of Jesus, Fr. Reuter passed away before the end of 2012 at age 96. Of the people on this list, he is the most beloved by Filipinos. The others range from from former soldiers to Jewish expatriates to counter insurgency experts and CIA operatives. Some were instrumental in starting businesses that were vital to the country. Quite a few married Filipinas. One was considered a rogue but contributed greatly to economic development. -

GREGORY the Natures of War FINAL May 2015

!1 The Natures of War Derek Gregory for Neil 1 In his too short life, Neil Smith had much to say about both nature and war: from his seminal discussion of ‘the production of nature’ in his first book, Uneven development, to his dissections of war in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries in American Empire – where he identified the ends of the First and Second World Wars as crucial punctuations in the modern genealogy of globalisation – and its coda, The endgame of globalization, a critique of America’s wars conducted in the shadows of 9/11. 2 And yet, surprisingly, he never linked the two. He was of course aware of their connections. He always insisted that the capitalist production of nature, like that of space, was never – could not be – a purely domestic matter, and he emphasised that the modern projects of colonialism and imperialism depended upon often spectacular displays of military violence. But he did not explore those relations in any systematic or substantive fashion. He was not alone. The great Marxist critic Raymond Williams once famously identified ‘nature’ as ‘perhaps the most complex word in the [English] language.’ Since he wrote, countless commentators have elaborated on its complexities, but few of them 1 This is a revised and extended version of the first Neil Smith Lecture, delivered at the University of St Andrews – Neil’s alma mater – on 14 November 2013. I am grateful to Catriona Gold for research assistance on the Western Desert, to Paige Patchin for lively discussions about porno-tropicality and the Vietnam war, and to Noel Castree, Dan Clayton, Deb Cowen, Isla Forsyth, Gastón Gordillo, Jaimie Gregory, Craig Jones, Stephen Legg and the editorial collective of Antipode for radically improving my early drafts. -

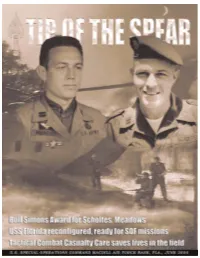

USSOCOM Tip of the Spear TCCC June 2006

TIP OF THE SPEAR Departments Global War On Terrorism Page 4 U.S. Army Special Operations Command Page 14 Naval Special Warfare Command Page 16 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command Page 26 Air Force Special Operations Command Page 28 Headquarters USSOCOM Page 31 Bull Simons Award goes to Meadows, Scholtes Col. Arthur “Bull” Simons is the namesake for Special Operations Forces most prestigious award. In November 1970, Simons led a mission to North Vietnam, to rescue 61 Prisoners of War from the Son Tay prison near Hanoi. USSOCOM photo. See page 20. Tip of the Spear Gen. Doug Brown Capt. Joseph Coslett This is a U.S. Special Operations Command publication. Contents are Commander, USSOCOM Chief, Command Information not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, Department of Defense or USSOCOM. The content is CSM Thomas Smith Mike Bottoms edited, prepared and provided by the USSOCOM Public Affairs Office, Command Sergeant Major Editor 7701 Tampa Point Blvd., MacDill AFB, Fla., 33621, phone (813) 828- 2875, DSN 299-2875. E-mail the editor via unclassified network at Col. Samuel T. Taylor III Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser [email protected]. The editor of the Tip of the Spear reserves Public Affairs Officer Editor the right to edit all copy presented for publication. Front cover: Retired Maj. Dick Meadows, left and retired Maj. Gen. Richard Scholtes, right are recognized with the Bull Simons Award. Photographic by Mike Bottoms. Tip of the Spear 2 Highlights Framing future of SOF through focus, organization, page 8 USS Florida modified to meet SOF missions, page 16 Tactical Combat Casualty Care saves lives on the battlefield, page 34 Tip of the Spear 3 GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM Interview with Gen. -

2013 6 Chem News.Pdf

P a g e | 1 CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter – December 2013 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com P a g e | 2 CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter – December 2013 . Virtual HUMINT™ vs. Terrorist CBRN Capabilities Source: http://www.cbrneportal.com/virtual-humint-vs-terrorist-cbrn-capabilities/ Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear open sources and, especially, deep web weapons are the “game-changers” that sources: jihadists all over the world aspire to get their A jihadist forum member posted hands on. Terrorist organizations and other approximately ten files containing non-state actors continue to seek bona fide presentations of biology courses in a WMDs in order to further their goals in most secure forum, stating that they “would be of macabre ways – if “terror” is the goal, CBRN is benefit to the fighters.” In late September Syrian regime forces seized several tunnels belonging to the Syrian rebels in the city of Tadmur, a suburb of Aleppo. Tubes with tablets of Phostoxin (aluminum phosphide) were discovered in the raid, in addition to IEDs, IED precursors and foreign car license plates. In mid-September, several Turkish websites published information about the indictment brought against the six members of Jabhat al-Nusra (JN) and Ahrar al-Sham. Five were Turkish citizens and one a Syrian, named Haytham surely the ideal means. Qassab. The Syrian was charged with The ubiquity and efficiency of internet means being a member of a terrorist organization that any piece of CBRN knowledge published and attempting to acquire weapons for a on terrorist online networks is immediately terrorist organization. Turkish authorities available to all terrorists everywhere. -

Shadow Commander: the Epic Story of Donald D. Blackburn#8213;Guerrilla Leader and Special Forces Hero Online

KoJ36 (Download free pdf) Shadow Commander: The Epic Story of Donald D. Blackburn#8213;Guerrilla Leader and Special Forces Hero Online [KoJ36.ebook] Shadow Commander: The Epic Story of Donald D. Blackburn#8213;Guerrilla Leader and Special Forces Hero Pdf Free Mike Guardia *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #375529 in Books 2011-12-19 2012-01-02Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.13 x .99 x 6.28l, 1.21 #File Name: 1612000657240 pages | File size: 52.Mb Mike Guardia : Shadow Commander: The Epic Story of Donald D. Blackburn#8213;Guerrilla Leader and Special Forces Hero before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Shadow Commander: The Epic Story of Donald D. Blackburn#8213;Guerrilla Leader and Special Forces Hero: 21 of 21 people found the following review helpful. Donald Blackburn's WWII Guerrilla Activities, Luzon, Philippines.By Leo HigginsThe author and historian Mike Guardia does a decent job at bringing retired United States Army, Brigadier General Donald D. Blackburn's biography to life. This book mirrors his previous work of the "American Guerrilla". In that narrative he writes about retired Brigadier General Russell W. Volkmann and his guerrilla activities against the Japanese Imperial Army during WWII on the northern island of Luzon, Republic of the Philippines, 1942 -1945. Both men escaped, (in tandem), the hellish realities of the Bataan Death March, and ultimately managed to galvanize the fighting spirit of the Filipino people. Their escape from the death march was quite miraculous, as the Japanese violently took control of the peaceful surrender of the allied troops. -

Fm 3-18 Special Forces Operations

FM 3-18 SPECIAL FORCES OPERATIONS M DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Distribution authorized to U.S. Government agencies and their contractors only to protect technical or operational information from automatic dissemination under the International Exchange Program or by other means. This determination was made on 13 May 2014. Other requests for this document must be referred to Commander, United States Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School, ATTN: AOJK-CDI-SFD, 3004 Ardennes Street, Stop A, Fort Bragg, NC 28310-9610. DESTRUCTION NOTICE: DESTRUCTION NOTICE. Destroy by any method that will prevent disclosure of contents or reconstruction of the document. FOREIGN DISCLOSURE RESTRICTION (FD 6): This publication has been reviewed by the product developers in coordination with the United States Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School foreign disclosure authority. This product is releasable to students from foreign countries on a case-by-case basis only. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online (https://armypubs.us.army.mil/doctrine/index.html). *FM 3-18 Field Manual Headquarters No. 3-18 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 28 May 2014 Special Forces Operations Contents Page PREFACE ............................................................................................................. iv INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... v Chapter 1 THE HISTORY OF UNITED STATES ARMY SPECIAL FORCES -

NBK2000 Guide.Pdf

NBK2000 Home page Welcome to NBK2000 Home of the Natural Born Killers of the 21st century "The knowledge that they fear is a weapon to be used against them" The mission of NBK2000 is to spread the knowledge needed to fight the war against the "War on Crime". Americas politicians have used the excuse of an (allegedly) rising crime rate as justification for destroying our constitutional rights, and for militarizing the police in preparation for dictatorship. So with the future of Big Brother hanging over our heads, it's time everyone wakes up to the truth and gets ready to fight. You can't fight the Goverment openly and hope to win. They'll burn you up like Waco or wait you out until you surrender and stick you in an underground prison like Marion, IL. You have to fight them covertly as an underground resistance fighter like the french against the Nazi occupation. You may be asking yourself "what does committing crimes like rape and murder have to do with fighting an oppressive goverment?" Simple, every resistance group uses assassination (murder) and torture (rape) as weapons against the agents of the State. And, of course, every fighter uses weapons to kill and destroy the agents and property of the State. You need money for bribes (robbery), supplies (burglary and fraud), transportation (GTA), etc. etc.. Below is a list of links for pages on almost every "crime", weapons you'll need to fight the police (or do the crime you want), skills you'll need to excel in crime, and links to penal codes so you'll know how much time you could get.