Strategic Thinking: How Special Forces Officers Can Influence Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

Hearing on the Filipino Veterans Equity Act of 2007

S. HRG. 110–70 HEARING ON THE FILIPINO VETERANS EQUITY ACT OF 2007 HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 11, 2007 Printed for the use of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35-645 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:59 Jun 25, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\RD41451\DOCS\35645.TXT SENVETS PsN: ROWENA COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho, Ranking Member PATTY MURRAY, Washington ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania BARACK OBAMA, Illinois RICHARD M. BURR, North Carolina BERNARD SANDERS, (I) Vermont JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia SHERROD BROWN, Ohio LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina JIM WEBB, Virginia KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JON TESTER, Montana JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada WILLIAM E. BREW, Staff Director LUPE WISSEL, Republican Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:59 Jun 25, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 H:\RD41451\DOCS\35645.TXT SENVETS PsN: ROWENA CONTENTS APRIL 11, 2007 SENATORS Page Akaka, Hon. Daniel K., Chairman, U.S. Senator from Hawaii ........................... 1 Prepared statement .......................................................................................... 5 Inouye, Hon. Daniel K., U.S. Senator from Hawaii ............................................. -

March 2021 Sentinel

Sentinel NEWSLETTER OF THE QUIET PROFESSIONALS SPECIAL FORCES ASSOCIATION CHAPTER 78 The LTC Frank J. Dallas Chapter VOLUME 12, ISSUE 3 • MARCH 2021 OPERATION GENIE UFOs — The Facts Graduation Special Forces Qualification Students Graduate Course, Don Green Berets Co A/5/19th SFG Reflagging Ceremony From the Editor VOLUME 12, ISSUE 3 • MARCH 2021 In last month’s issue we highlighted a fellow IN THIS ISSUE: paratrooper who, among other things, on 6 President’s Page .............................................................. 1 January, 2021 taunted part of the attacking mob and led them away from the Senate Operation Genie .............................................................. 2 US ARMY SPECIAL chambers. The Senate voted to award Eugene OPS COMMAND Book Review: Shadow Commander: The Epic Story of Goodman the Congressional Gold Medal by Donald D. Blackburn— Guerrilla Leader and unanimous consent. Special Forces Hero by Mike Guardia ............................. 4 Kenn Miller writes that while Special Forces US Army History: The Story of Sergeant John Clem, How Miller exploits are often seen to be stealthy or US ARMY JFK SWCS The Boy Soldier ............................................................... 5 Sentinel Editor kinetic, there is another part of the mission that is largely overlooked. Going back to the UFOs — The Facts ....................................................................6 OSS in World War II, PSYOPS has always been an integral part of Graduation: Special Forces Qualification Students the mission. My A team in Vietnam, for example, had a third officer, Graduate Course, Don Green Berets ........................... 12 a 2LT, who was assigned to PSYOPS. 1ST SF COMMAND Chapter 78 February Meeting — MAJ (R) Raymond P. Ambrozak was such a standout in the field Co A/5/19th SFG Reflagging Ceremony ....................... -

Yanks Among the Pinoys Preface

Yanks Among the Pinoys Preface: No narrative of the Philippines would be complete without considering the outsize influence of various Americans who left an indelible mark on the country before and after independence in 1946. (The Philippines celebrates June 12, 1898 as its Independence Day but that is another story.) Except for one or two, these men - there is only one woman - are unknown among contemporary Filipinos. I have skipped more well known Americans such as William Howard Taft , Douglas MacArthur or Dwight Eisenhower. They all had a sojourn in the Philippines. I omitted the names of several American Army officers who refused to surrender to the Japanese after the fall of Bataan and Corregidor in April and May of 1942. These officers formed large Filipino guerrilla armies which tied up the occupying forces in knots. Among them were Donald Blackburn, Wendell Fertig and Russell Volckman. They have been given enough credit in books and even movies. The motivations of these Americans to stay in the country are probably as diverse as their personalities. Only Fr. James Reuter probably had a clear vision on why he came in the first place. A priest belonging to the Society of Jesus, Fr. Reuter passed away before the end of 2012 at age 96. Of the people on this list, he is the most beloved by Filipinos. The others range from from former soldiers to Jewish expatriates to counter insurgency experts and CIA operatives. Some were instrumental in starting businesses that were vital to the country. Quite a few married Filipinas. One was considered a rogue but contributed greatly to economic development. -

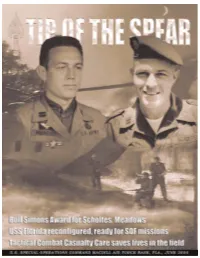

USSOCOM Tip of the Spear TCCC June 2006

TIP OF THE SPEAR Departments Global War On Terrorism Page 4 U.S. Army Special Operations Command Page 14 Naval Special Warfare Command Page 16 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command Page 26 Air Force Special Operations Command Page 28 Headquarters USSOCOM Page 31 Bull Simons Award goes to Meadows, Scholtes Col. Arthur “Bull” Simons is the namesake for Special Operations Forces most prestigious award. In November 1970, Simons led a mission to North Vietnam, to rescue 61 Prisoners of War from the Son Tay prison near Hanoi. USSOCOM photo. See page 20. Tip of the Spear Gen. Doug Brown Capt. Joseph Coslett This is a U.S. Special Operations Command publication. Contents are Commander, USSOCOM Chief, Command Information not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, Department of Defense or USSOCOM. The content is CSM Thomas Smith Mike Bottoms edited, prepared and provided by the USSOCOM Public Affairs Office, Command Sergeant Major Editor 7701 Tampa Point Blvd., MacDill AFB, Fla., 33621, phone (813) 828- 2875, DSN 299-2875. E-mail the editor via unclassified network at Col. Samuel T. Taylor III Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser [email protected]. The editor of the Tip of the Spear reserves Public Affairs Officer Editor the right to edit all copy presented for publication. Front cover: Retired Maj. Dick Meadows, left and retired Maj. Gen. Richard Scholtes, right are recognized with the Bull Simons Award. Photographic by Mike Bottoms. Tip of the Spear 2 Highlights Framing future of SOF through focus, organization, page 8 USS Florida modified to meet SOF missions, page 16 Tactical Combat Casualty Care saves lives on the battlefield, page 34 Tip of the Spear 3 GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM Interview with Gen. -

Shadow Commander: the Epic Story of Donald D. Blackburn#8213;Guerrilla Leader and Special Forces Hero Online

KoJ36 (Download free pdf) Shadow Commander: The Epic Story of Donald D. Blackburn#8213;Guerrilla Leader and Special Forces Hero Online [KoJ36.ebook] Shadow Commander: The Epic Story of Donald D. Blackburn#8213;Guerrilla Leader and Special Forces Hero Pdf Free Mike Guardia *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #375529 in Books 2011-12-19 2012-01-02Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.13 x .99 x 6.28l, 1.21 #File Name: 1612000657240 pages | File size: 52.Mb Mike Guardia : Shadow Commander: The Epic Story of Donald D. Blackburn#8213;Guerrilla Leader and Special Forces Hero before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Shadow Commander: The Epic Story of Donald D. Blackburn#8213;Guerrilla Leader and Special Forces Hero: 21 of 21 people found the following review helpful. Donald Blackburn's WWII Guerrilla Activities, Luzon, Philippines.By Leo HigginsThe author and historian Mike Guardia does a decent job at bringing retired United States Army, Brigadier General Donald D. Blackburn's biography to life. This book mirrors his previous work of the "American Guerrilla". In that narrative he writes about retired Brigadier General Russell W. Volkmann and his guerrilla activities against the Japanese Imperial Army during WWII on the northern island of Luzon, Republic of the Philippines, 1942 -1945. Both men escaped, (in tandem), the hellish realities of the Bataan Death March, and ultimately managed to galvanize the fighting spirit of the Filipino people. Their escape from the death march was quite miraculous, as the Japanese violently took control of the peaceful surrender of the allied troops. -

Fm 3-18 Special Forces Operations

FM 3-18 SPECIAL FORCES OPERATIONS M DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Distribution authorized to U.S. Government agencies and their contractors only to protect technical or operational information from automatic dissemination under the International Exchange Program or by other means. This determination was made on 13 May 2014. Other requests for this document must be referred to Commander, United States Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School, ATTN: AOJK-CDI-SFD, 3004 Ardennes Street, Stop A, Fort Bragg, NC 28310-9610. DESTRUCTION NOTICE: DESTRUCTION NOTICE. Destroy by any method that will prevent disclosure of contents or reconstruction of the document. FOREIGN DISCLOSURE RESTRICTION (FD 6): This publication has been reviewed by the product developers in coordination with the United States Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School foreign disclosure authority. This product is releasable to students from foreign countries on a case-by-case basis only. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online (https://armypubs.us.army.mil/doctrine/index.html). *FM 3-18 Field Manual Headquarters No. 3-18 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 28 May 2014 Special Forces Operations Contents Page PREFACE ............................................................................................................. iv INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... v Chapter 1 THE HISTORY OF UNITED STATES ARMY SPECIAL FORCES -

PB 80–96–1 January 1996 Vol. 9, No. 1

Special Warfare The Professional Bulletin of the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School PB 80–96–1 January 1996 Vol. 9, No. 1 From the Commandant Special Warfare With the proliferation of sophisticated weapons systems and the increased efficien- cy of intelligence-gathering and information processing, technology offers a variety of options in dealing with our current ambigu- ous operations spectrum. Special-operations forces place a high pre- mium on technology — the nature of our operations demands that we take advan- tage of every means to provide an immedi- ate, effective response. In this issue, Steven Metz and Lieutenant Colonel James Kievit discuss how emerging technology and the ensuing revolution in military affairs can be applied to conflict short of war, an area in which SOF are often involved. But through siren song of technology, but we must a hypothetical scenario, they also show the remember that the main thing is to keep the hidden costs that such an application of main thing the main thing. technology might entail. The main thing is best stated by General While we consider the importance of tech- Dennis Reimer, when he says, “The idea of nology and the need to stay abreast of it, we war in the Information Age will conjure up must not become so enamored of technology images of bloodless conflict, more like a com- that we forget the reason behind our need puter game than the bloody wars we’ve for it: soldiers. We have always said that known in the past. Nothing could be further humans are more important than hardware. -

Richard J. Meadows Major, US Army (Retired) “Quiet Professional”

Richard J. Meadows Major, US Army (Retired) “Quiet Professional” 1 Table of Contents Dick Meadows: A Quiet Professional By Captain Jay Ashburner Son-Tay Raid œ 25 th Anniversary Daring POW Raid at Son Tay A Special Kind of Hero Story by Heike Hasenauer A Special Warrior‘s Last Patrol: Dick Meadows, by Maj. John L. Plaster, USAR (Ret.) Statement from President Clinton Richard J. —Dick“ Meadows Award Perot helps honor Special Operator, By Henry Cunningham, Military editor Tribute to a Hero, by Major R.G. —Bob“ Davis, Retired SOG: The Secret Wars of America‘s Commandos in Vietnam, Excerpts from Chapter 3: First Blood, and Chapter 4: Code Name Bright Light Application for Award 2 1931 - 1995 “Repeatedly answering our country’s call and taking on the most dangerous and sensitive missions, few have been as willing to put themselves in harms way for their fellow country men.” The White House, Washington, DC July 26, 1995 Dick Meadows: A Quiet Professional By Captain Jay Ashburner On July 29, 1995, the special operations community lost a true legend with the passing of retired Major Richard J. “Dick” Meadows. His extraordinary exploits spanned more than three decades and included the most widely known and defining missions in the history of U.S. Special Operations. Dick Meadows exemplified devotion to duty, serving as a noncommissioned officer, as a commissioned officer, and after his retirement, as a civilian special consultant (read operator) to U.S. Army Special Forces and the joint SOF community. Meadows was born June 16, 1931, in rural Virginia and enlisted in the Army in August 1947, at the age of 16. -

June 2014.Qxd

HowardHoward receivesreceives 20142014 BullBull SimonsSimons AwardAward ...... 1414 TipTip ofof thethe SpearSpear Adm. William H. McRaven This is a U.S. Special Operations Command publication. Contents are not Commander, USSOCOM necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, Department of Defense or USSOCOM. The content is edited, prepared and provided by the USSOCOM Public Affairs Office, 7701 Tampa Point Blvd., CSM Chris Faris MacDill AFB, Fla., 33621, phone (813) 826-4600, DSN 299-4600. An Command Sergeant Major electronic copy can be found at www.socom.mil. E-mail the editor via unclassified network at [email protected]. The editor of the Tip of the Spear reserves the right to edit all copy presented for publication. Ken McGraw Marine Corps Master Sgt. F. B. Zimmerman Air Force Tech. Sgt. Heather Kelly Public Affairs Director Staff NCOIC, Command Information Staff Writer/Photographer Mike Bottoms Air Force Master Sgt. Larry W. Carpenter, Jr. Air Force Tech. Sgt. Angelita Lawrence Managing Editor Staff Writer/Photographer Staff Writer/Photographer (Cover) Medal of Honor recipient and Special Operations legend, Army Col. Robert L. Howard, is USSOCOM’s 2014 Bull Simons Award recipient. The Bull Simons Award is USSOCOM’s highest honor and was first awarded in 1990. The award recognizes recipients who embody “the true spirit, values, and skills of a Special Operations warrior.” Col. Arthur “Bull” Simons, whom the award is named after, was the epitome of these attributes. Photo illustration by Ana Bruno-Stump. Tip of the Spear 2 Highlights Departments SOF Around the World SOCSOUTH, Domincan Republic training exchange .. -

Alamo Scouts Diary

McGowen Team after the 1st Alamo Scout mission, the reconnaissance of Los Negros Island, New Guinea, 27-28 Feb 1944. Al amo Scouts D ia r y By Kenneth Finlayson Vol. 4 No. 3 1 s t ed at 7:00 p.m. by Navy PT boat onto battle in the village and waited until 5:30 before attacking Ithen deserteder beach, the small team moved stealthily along the guard post from two sides, killing the four enemy the trail until it reached its objective at 2:00 a.m. Two local soldiers. After neutralizing the guard post, the team guides were sent into the tiny village to obtain the latest moved to the pick-up point, secured the area, and made information on the enemy disposition and ascertain the radio contact to bring in the boats for the evacuation. The status of the personnel held hostage there. On the guide’s main body with the newly-freed hostages soon arrived. return, the team leader modified his original plan based By 7:00 a.m., everyone was safely inside friendly lines.1 on their information and the men dispersed to take up This well-planned, flawlessly executed hostage rescue their positions. could easily have come from today’s war on terrorism. In The leader with six team members, the interpreter, reality, it took place on 4 October 1944 at Cape Oransbari, and three local guides moved to the vicinity of a large New Guinea. The team that rescued sixty-six Dutch and building where eighteen enemy soldiers slept inside. Two Javanese hostages from the Japanese were part of the Sixth team members and one native guide took up a position U.S. -

The Guerrilla Resistance Against the Japanese in the Philippines During World War II

Awaiting the Allies’ Return: The Guerrilla Resistance Against the Japanese in the Philippines during World War II Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University James A. Villanueva Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Dr. Peter R. Mansoor, Advisor Dr. Mark Grimsley Dr. Bruno Cabanes Copyright by James Alexander Villanueva 2019 Abstract During World War II, guerrillas from across the Philippines opposed Imperial Japan’s occupation of the archipelago. While the guerrillas often fought each other and were never strong enough to overcome the Japanese occupation on their own, they disrupted Japanese operations, kept the spirit of resistance to Japanese occupation alive, provided useful intelligence to the Allies, and assumed frontline duties fighting the Japanese following the Allies’ landing in 1944. By examining the organization, motivations, capabilities, and operations of the guerrillas, this dissertation argues that the guerrillas were effective because Japanese punitive measures pushed the majority of the population to support them, as did a strong sense of obligation and loyalty to the United States. The guerrillas benefitted from the fact that many islands in the Philippines had weak Japanese garrisons, enabling those resisting the Japanese to build safe bases and gain and train recruits. Unlike their counterparts opposing the Americans in 1899, the guerrillas during World War II benefitted from the leadership of American and Filipino military personnel, and also received significant aid and direction from General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area Headquarters. The guerrillas in the Philippines stand as one of the most effective and sophisticated resistance movements in World War II, comparing favorably to Yugoslavian and Russian partisans in Europe.