Forging the Masculine and Modern Nation: Race, Identity, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1 PETER C. BJARKMAN www.bjarkman.com Cuban Baseball Historian Author and Internet Journalist Post Office Box 2199 West Lafayette, IN 47996-2199 USA IPhone Cellular 1.765.491.8351 Email [email protected] Business phone 1.765.449.4221 Appeared in “No Reservations Cuba” (Travel Channel, first aired July 11, 2011) with celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain Featured in WALL STREET JOURNAL (11-09-2010) front page story “This Yanqui is Welcome in Cuba’s Locker Room” PERSONAL/BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Born: May 19, 1941 (72 years old), Hartford, Connecticut USA Terminal Degree: Ph.D. (University of Florida, 1976, Linguistics) Graduate Degrees: M.A. (Trinity College, 1972, English); M.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1970, Education) Undergraduate Degree: B.S.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1963, Education) Languages: English and Spanish (Bilingual), some basic Italian, study of Japanese Extensive International Travel: Cuba (more than 40 visits), Croatia /Yugoslavia (20-plus visits), Netherlands, Italy, Panama, Spain, Austria, Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala, Canada, Japan. Married: Ronnie B. Wilbur, Professor of Linguistics, Purdue University (1985) BIBLIOGRAPHY March 2014 MAJOR WRITING AWARDS 2008 Winner – SABR Latino Committee Eduardo Valero Memorial Award (for “Best Article of 2008” in La Prensa, newsletter of the SABR Latino Baseball Research Committee) 2007 Recipient – Robert Peterson Recognition Award by SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee, for advancing public awareness -

STATE CHAMPIONSHIP: Pilot Point Vs

STATE CHAMPIONSHIP: Pilot Point vs. Kirbyville For the first time all year we allowed ourselves to celebrate a win for more than a few hours. We really got to enjoy the weekend and soak in that we had made it to the state championship game. Monday morning however; that was over. Making the state championship game was not our goal. Winning the state championship game was our goal. That was the mentality we showed up with Monday morning. I think that something that made our group special was our ability to put everything aside and just focus on football. We approached that week like we did on the first day of two-a-days. Business like. If an outsider were to come in our field house, there would have been no way to tell that we were playing for the state championship in 6 days. The focus was entirely on the opponent and what our jobs were to be Saturday afternoon. Kirbyville was the first team we were going to match-up against that had more big game experience than we did. Kirbyville had made the state championship in 2008 and lost to the Muleshoe Mules just like we did. A tough loss for them, but the experience they gained could potentially be an edge for them. Kirbyville entered the state championship with a record of 12-2 but their 2 losses weren’t just normal losses. Kirbyville did something similar to us and loaded their schedule with 3A teams to test themselves early. Their losses were both close, and came to West Orange Stark and Jasper, both of which were 3A powers. -

The Musical Antiquary (1909-1913) Copyright © 2003 RIPM Consortium Ltd Répertoire International De La Presse Musicale (

Introduction to: Richard Kitson, The Musical Antiquary (1909-1913) Copyright © 2003 RIPM Consortium Ltd Répertoire international de la presse musicale (www.ripm.org) The Musical Antiquary (1909-1913) The Musical Antiquary [MUA] was published in Oxford from October 1909 to July 1913 by Oxford University Press. The quarterly issues of each volume1-which contain between sixty and eighty pages in a single-column format-are paginated consecutively (each beginning with page one) and dated but not individually numbered. The price of each issue was two shillings and sixpence. Publication ceased without explanation. The Musical Antiquary was among the first British music journals to deal with musicological subjects, and contained articles of historical inquiry dealing mainly with "ancient music": the Elizabethan, the British Commonwealth and Restoration periods, and eighteenth-century musicians and musical life. In addition, several articles deal with early manifestations of Christian chant, the techniques of Renaissance polyphony and topics dealing with Anglican and Roman Catholic liturgical practices. The journal's founder and editor was Godfrey Edward Pellew Arkwright (1864-1944), a tireless scholar deeply involved with the study of music history. Educated at the University of Oxford, Arkwright prepared the catalogue of music in the Library of Christ Church, Oxford, and edited several important publications: English vocal music in twenty-five volumes of the Old English Edition, and Purcell's Birthday Odes for Queen Mary and his Odes to St. Cecilia, both published by the Purcell Society.2 The main contribiitors to The Musical Antiquary are well-known scholars in the field of British musicology, all born in about the middle of the nineteenth century and all active through the first quarter of the twentieth. -

World Latin American Agenda 2016

World Latin American Agenda 2016 In its category, the Latin American book most widely distributed inside and outside the Americas each year. A sign of continental and global communion among individuals and communities excited by and committed to the Great Causes of the Patria Grande. An Agenda that expresses the hope of the world’s poor from a Latin American perspective. A manual for creating a different kind of globalization. A collection of the historical memories of militancy. An anthology of solidarity and creativity. A pedagogical tool for popular education, communication and social action. From the Great Homeland to the Greater Homeland. Our cover image by Maximino CEREZO BARREDO. See all our history, 25 years long, through our covers, at: latinoamericana.org/digital /desde1992.jpg and through the PDF files, at: latinoamericana.org/digital This year we remind you... We put the accent on vision, on attitude, on awareness, on education... Obviously, we aim at practice. However our “charisma” is to provoke the transformations of awareness necessary so that radically new practices might arise from another systemic vision and not just reforms or patches. We want to ally ourselves with all those who search for that transformation of conscience. We are at its service. This Agenda wants to be, as always and even more than at other times, a box of materials and tools for popular education. latinoamericana.org/2016/info is the web site we have set up on the network in order to offer and circulate more material, ideas and pedagogical resources than can economically be accommo- dated in this paper version. -

Por Amor a La Pelota: Once Cracks De La Ficción Futbolera

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications 2014 Por Amor a la Pelota: Once Cracks de la Ficción Futbolera Shawn Stein Dickinson College Nicolás Campisi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Fiction Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Stein, Shawn, and Nicolás Campisi, eds. Por Amor a la Pelota: Once Cracks de la Ficción Futbolera . Santiago: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2014. This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ÚLTIMOS TÍTULOS POR AMOR A LA PELOTA: SHAWN STEIN es del estado de Colorado en los Estados Unidos. Es doctor en litera- ONCE CRACKS DE LA FICCIÓN tura latinoamericana de la Universidad de • La fábula de la evolución (novela 2013) FUTBOLERA California, Riverside. Fue docente e inves- EUGENIO NORAMBUENA PINTO tigador en Massey University en Nueva Zelanda y actualmente es profesor asocia- • Confidencias de un locutor (crónicas, 2013) do en Washington College en Maryland, PATRICIO BAÑADOS Selva Almada Estados Unidos, donde enseña letras lati- • La porcelana de Sofía (novela, 2013) noamericanas, con enfoque en los estudios VERÓNICA KÖHLER-VARGAS Edmundo Paz Soldán culturales y literarios. Ha presentado sus proyectos de investigación sobre la sátira • Fuera del Colegio! Una señal de narrativa, el cine y la ficción de fútbol en traetormentas (novela, 2013) Sérgio Sant’Anna congresos internacionales en varios países FABIO SALAS ZÚÑIGA de Europa, Oceanía y las Américas. -

Fitment Chart (Pdf)

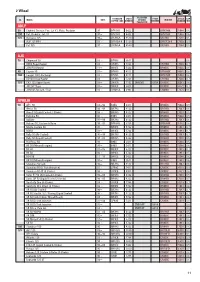

2 Wheel PLATINUM CC MODEL DATE STANDARD STOCK OR GOLD STOCK IRIDIUM STOCK GAP COPPER CORE NUMBER PALLADIUM NUMBER NUMBER MM ADLY 50 Citybird, Crosser, Fox, Jet X1, Pista, Predator 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 100 Cat, Predator, Jet, X1 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 125 Activator 125 99 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJP 125 PR4 03 DPR7EA-9 5129 DPR7EIX-9 7803 0.9 Cat 125 97 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJS 50 Chipmunk 50 03 BP4HS 3611 0.6 DD50 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 JSM 50 Motard 11 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 80 Coyote 80 03 BP6HS 4511 BPR6HIX 4085 0.6 100 Cougar 100 (Jincheng) 03 BP7HS 5111 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 DD100 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 125 CR3-125 Super Sports 08 DR8EA 7162 DR8EVX 6354 DR8EIX 6681 0.6 JS125Y Tiger 03 DR8ES 5423 DR9EIX 4772 0.7 JSM125 Motard / Trail 10 CR6HSA 2983 CR6HIX 7274 0.6 APRILIA 50 AF1 50 8892 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Amico 50 9294 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Area 51 (Liquid Cooled 2-Stroke) 98 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Extrema 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Gulliver 9799 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Habana 50, Custom & Retro 9905 BPR8HS 3725 BPR8HIX 6742 0.6 Mojito Custom 50 05 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 MX50 03 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 Rally 50 (Air Cooled) 9599 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.7 Rally 50 (Liquid Cooled) 9703 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Red Rose 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 RS 50 (Minarelli engine) 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 RS 50 0105 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 RS 50 06 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.5 RS4 50 1113 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 ‡ Early Ducati Testastretta bikes (749, 998, 999 models) can have very little clearance between the plug hex and the RX 50 (Minarelli engine) 97 B9ES 2611 BR9EIX 3981 0.6 cylinder head that may require a thin walled socket, no larger than 20.5mm OD to allow the plug to be fitted. -

Culture Box of Cuba

CUBA CONTENIDO CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................3 Introduction .................................6 Items .............................................8 More Information ........................89 Contents Checklist ......................108 Evaluation.....................................110 AGRADECIMIENTOS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contributors The Culture Box program was created by the University of New Mexico’s Latin American and Iberian Institute (LAII), with support provided by the LAII’s Title VI National Resource Center grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Contributing authors include Latin Americanist graduate students Adam Flores, Charla Henley, Jennie Grebb, Sarah Leister, Neoshia Roemer, Jacob Sandler, Kalyn Finnell, Lorraine Archibald, Amanda Hooker, Teresa Drenten, Marty Smith, María José Ramos, and Kathryn Peters. LAII project assistant Katrina Dillon created all curriculum materials. Project management, document design, and editorial support were provided by LAII staff person Keira Philipp-Schnurer. Amanda Wolfe, Marie McGhee, and Scott Sandlin generously collected and donated materials to the Culture Box of Cuba. Sponsors All program materials are readily available to educators in New Mexico courtesy of a partnership between the LAII, Instituto Cervantes of Albuquerque, National Hispanic Cultural Center, and Spanish Resource Center of Albuquerque - who, together, oversee the lending process. To learn more about the sponsor organizations, see their respective websites: • Latin American & Iberian Institute at the -

Dur 04/06/2017

DOMINGO 4 DE JUNIO DE 2017 4 NACIONAL EN CORTO PANCRACIO LUCHA LIBRE Tamaulipas sobresale en gimnasia rítmica de ON 2017 La representación de Tamaulipas dominó y sobresalió en la gimnasia rítmica de la Olimpiada Nacional 2017, que se desarrolla en la “Sultana del Norte”. Norma Cobos, de apenas 10 años de edad, deslum- Revancha bró en las instalaciones del Gimnasio Nuevo León Gonzalitos, luego de colgarse cuatro medallas de oro gracias a su entusiasmo, gracia, calidad, armonía y belleza. Cobos Arteaga obtuvo el primer lugar por equi- entre gladiadores pos, en all around, aro y pelota, además consiguió dos metales más para ser la máxima ganadora de la com- petencia Sumó una plata en manos libres y un bron- EL UNIVERSAL ce en cuerda. CDMX El Último Guerrero siempre Montemayor y Alanís, final B en ha sido un hombre de retos Copa del Mundo de Canotaje y en varias ocasiones ha ma- nifestado su intención de ju- La dupla mexicana conformada por Maricela Montema- garse su cabellera contra yor y Karina Alanís disputarán la final B de la Copa del Atlantis quien hace tres Mundo de Canotaje, que se desarrolla en esta capital. años lo despojó de su tapa. En la modalidad de doble kayak distancia de 500 Sin embargo, en la histo- metros (K2-500) las canoístas tricolores ya no podrán ria de la lucha libre hay va- pelear medallas debido a que se colocaron en el quin- rios gladiadores que han per- to sitio dentro de la fase de semifinales, celebradas dido su capucha; luego por su este sábado. -

Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Copyright By Omar Gonzalez 2019 A History of Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 A Historyof Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez This thesishas beenacce ted on behalf of theDepartment of History by their supervisory CommitteeChair 6 Kate Mulry, PhD Cliona Murphy, PhD DEDICATION To my wife Berenice Luna Gonzalez, for her love and patience. To my family, my mother Belen and father Jose who have given me the love and support I needed during my academic career. Their efforts to raise a good man motivates me every day. To my sister Diana, who has grown to be a smart and incredible young woman. To my brother Mario, whose kindness reaches the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada and who has been an inspiration in my life. And to my twin brother Miguel, his incredible support, his wisdom, and his kindness have not only guided my life but have inspired my journey as a historian. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is a result of over two years of research during my time at CSU Bakersfield. First and foremost, I owe my appreciation to Dr. Stephen D. Allen, who has guided me through my challenging years as a graduate student. Since our first encounter in the fall of 2016, his knowledge of history, including Mexican boxing, has enhanced my understanding of Latin American History, especially Modern Mexico. -

William J. Hammer Collection

William J. Hammer Collection Mark Kahn, 2003; additional information added by Melissa A. N. Keiser, 2021 2003 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Professional materials............................................................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs and other materials............................................................ 13 William J. Hammer Collection NASM.XXXX.0074 Collection Overview Repository: National Air and Space Museum Archives Title: William J. Hammer Collection Identifier: NASM.XXXX.0074 Date: -

Control Biológico De Insectos: Clara Inés Nicholls Estrada Un Enfoque Agroecológico

Control biológico de insectos: Clara Inés Nicholls Estrada un enfoque agroecológico Control biológico de insectos: un enfoque agroecológico Clara Inés Nicholls Estrada Ciencia y Tecnología Editorial Universidad de Antioquia Ciencia y Tecnología © Clara Inés Nicholls Estrada © Editorial Universidad de Antioquia ISBN: 978-958-714-186-3 Primera edición: septiembre de 2008 Diseño de cubierta: Verónica Moreno Cardona Corrección de texto e indización: Miriam Velásquez Velásquez Elaboración de material gráfico: Ana Cecilia Galvis Martínez y Alejandro Henao Salazar Diagramación: Luz Elena Ochoa Vélez Coordinación editorial: Larissa Molano Osorio Impresión y terminación: Imprenta Universidad de Antioquia Impreso y hecho en Colombia / Printed and made in Colombia Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial, por cualquier medio o con cualquier propósito, sin autorización escrita de la Editorial Universidad de Antioquia. Editorial Universidad de Antioquia Teléfono: (574) 219 50 10. Telefax: (574) 219 50 12 E-mail: [email protected] Sitio web: http://www.editorialudea.com Apartado 1226. Medellín. Colombia Imprenta Universidad de Antioquia Teléfono: (574) 219 53 30. Telefax: (574) 219 53 31 El contenido de la obra corresponde al derecho de expresión del autor y no compromete el pensamiento institucional de la Universidad de Antioquia ni desata su responsabilidad frente a terceros. El autor asume la responsabilidad por los derechos de autor y conexos contenidos en la obra, así como por la eventual información sensible publicada en ella. Nicholls Estrada, Clara Inés Control biológico de insectos : un enfoque agroecológico / Clara Inés Nicholls Estrada. -- Medellín : Editorial Universidad de Antioquia, 2008. 282 p. ; 24 cm. -- (Colección ciencia y tecnología) Incluye glosario. Incluye bibliografía e índices. -

Havanareporter YEAR VI

THE © YEAR VI Nº 7 APR, 6 2017 HAVANA, CUBA avana eporter ISSN 2224-5707 YOUR SOURCE OF NEWS & MORE H R Price: A Bimonthly Newspaper of the Prensa Latina News Agency 1.00 CUC, 1.00 USD, 1.20 CAN Caribbean Cooperation on Sustainable Development P. 3 P. 4 Cuba Health & Economy Sports Maisí Draws Tourists Science Valuable Cuban Boxing to Cuba’s Havana Hosts Sugar by Supports Enhanced Far East Regional Disability Products Transparency P.3 Conference P. 5 P. 13 P. 15 2 Cuba´s Beautiful Caribbean Keys By Roberto F. CAMPOS Many tourists who come to Cuba particularly love the beak known as Coco or White Ibis. Cayo Santa Maria, in Cuba’s the north-central region “Cayos” and become enchanted by their beautiful and Adjacent to it are the Guillermo and Paredón has become a particularly popular choice because of its very well preserved natural surroundings and range of Grande keys, which are included in the region´s tourism wonderful natural beauty, its infrastructure and unique recreational nautical activities. development projects. Cuban culinary traditions. These groups of small islands include Jardines del Rey Cayo Coco is the fourth largest island in the Cuban 13km long, two wide and boasting 11km of prime (King´s Gardens), one of Cuba´s most attractive tourist archipelago with 370 square kilometers and 22 beachfront, Cayo Santa María has small islands of destinations, catering primarily to Canadian, British kilometers of beach. pristine white sands and crystal clear waters. and Argentine holidaymakers, who praise the natural Cayo Guillermo extends to 13 square kilometers Other outstandingly attractive islets such as environment, infrastructure and service quality.