Download the Course Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lowest Temperature 10 January 1982

Sunday 10 January 1982 (Lowest recorded temperature in the United Kingdom) Weather chart for 1200 UTC on 10 January 1982 General summary After a mostly dry night, Northern Ireland and much of Scotland had a dry, bright and frosty day, though there were snow and hail showers in the extreme north of Scotland. It was very cold, with a very severe overnight frost. The temperature at Braemar, equalled the record, (also set in Braemar on 11 February 1895) for the lowest officially recorded temperature in Britain (-27.2 °C). Wales and much of England was dry and bright, though southern counties were cloudy, with rain, sleet or snow in South West England. It was bitterly cold with a keen easterly wind adding to the severity of the overnight frost, whilst in Shropshire, sheltered from the wind by hills to the east, the temperature fell to a new English record low of -26.1 °C at Newport. Significant weather event The minimum temperature of -27.2 °C at Braemar, Aberdeenshire, equalled the previous lowest officially recorded temperature in Britain which was also set at Braemar on 11 February 1895. This temperature was equalled again at Altnaharra, Highland, on 30 December 1995. Lowest temperatures in Scotland: Braemar, Aberdeenshire -27.2 °C Lagganlia, Inverness-shire -24.1 °C Balmoral, Aberdeenshire -23.5 °C Lowest temperatures in England: Newport, Shropshire -26.1 °C Shawbury, Shropshire -20.8 °C Maps from the daily weather summary showing the minimum and maximum temperatures for 10th January 1982. Daily weather extremes Highest Maximum Temperature -

North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016-2026

North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016-2026 North Highland Forest District North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016 - 2026 Plan Reference No:030/516/402 Plan Approval Date:__________ Plan Expiry Date:____________ | North Sutherland LMP | NHFD Planning | North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016-2026 Contents 4.0 Analysis and Concept 4.1 Analysis of opportunities I. Background information 4.2 Concept Development 4.3 Analysis and concept table 1.0 Introduction: Map(s) 4 - Analysis and concept map 4.4. Land Management Plan brief 1.1 Setting and context 1.2 History of the plan II. Land Management Plan Proposals Map 1 - Location and context map Map 2 - Key features – Forest and water map 5.0. Summary of proposals Map 3 - Key features – Environment map 2.0 Analysis of previous plan 5.1 Forest stand management 5.1.1 Clear felling 3.0 Background information 5.1.2 Thinning 3.1 Physical site factors 5.1.3 LISS 3.1.1 Geology Soils and landform 5.1.4 New planting 3.1.2 Water 5.2 Future habitats and species 3.1.2.1 Loch Shin 5.3 Restructuring 3.1.2.2 Flood risk 5.3.1 Peatland restoration 3.1.2.3 Loch Beannach Drinking Water Protected Area (DWPA) 5.4 Management of open land 3.1.3 Climate 5.5 Deer management 3.2 Biodiversity and Heritage Features 6.0. Detailed proposals 3.2.1 Designated sites 3.2.2 Cultural heritage 6.1 CSM6 Form(s) 3.3 The existing forest: 6.2 Coupe summary 3.3.1 Age structure, species and yield class Map(s) 5 – Management coupes (felling) maps 3.3.2 Site Capability Map(s) 6 – Future habitat maps 3.3.3 Access Map(s) 7 – Planned -

List of Vascular Plants Endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020

British & Irish Botany 2(3): 169-189, 2020 List of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020 Timothy C.G. Rich Cardiff, U.K. Corresponding author: Tim Rich: [email protected] This pdf constitutes the Version of Record published on 31st August 2020 Abstract A list of 804 plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands is broken down by country. There are 659 taxa endemic to Britain, 20 to Ireland and three to the Channel Islands. There are 25 endemic sexual species and 26 sexual subspecies, the remainder are mostly critical apomictic taxa. Fifteen endemics (2%) are certainly or probably extinct in the wild. Keywords: England; Northern Ireland; Republic of Ireland; Scotland; Wales. Introduction This note provides a list of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands, updating the lists in Rich et al. (1999), Dines (2008), Stroh et al. (2014) and Wyse Jackson et al. (2016). The list includes endemics of subspecific rank or above, but excludes infraspecific taxa of lower rank and hybrids (for the latter, see Stace et al., 2015). There are, of course, different taxonomic views on some of the taxa included. Nomenclature, taxonomic rank and endemic status follows Stace (2019), except for Hieracium (Sell & Murrell, 2006; McCosh & Rich, 2018), Ranunculus auricomus group (A. C. Leslie in Sell & Murrell, 2018), Rubus (Edees & Newton, 1988; Newton & Randall, 2004; Kurtto & Weber, 2009; Kurtto et al. 2010, and recent papers), Taraxacum (Dudman & Richards, 1997; Kirschner & Štepànek, 1998 and recent papers) and Ulmus (Sell & Murrell, 2018). Ulmus is included with some reservations, as many taxa are largely vegetative clones which may occasionally reproduce sexually and hence may not merit species status (cf. -

Condition of Designated Sites

Scottish Natural Heritage Condition of Designated Sites Contents Chapter Page Summary ii Condition of Designated Sites (Progress to March 2010) Site Condition Monitoring 1 Purpose of SCM 1 Sites covered by SCM 1 How is SCM implemented? 2 Assessment of condition 2 Activities and management measures in place 3 Summary results of the first cycle of SCM 3 Action taken following a finding of unfavourable status in the assessment 3 Natural features in Unfavourable condition – Scottish Government Targets 4 The 2010 Condition Target Achievement 4 Amphibians and Reptiles 6 Birds 10 Freshwater Fauna 18 Invertebrates 24 Mammals 30 Non-vascular Plants 36 Vascular Plants 42 Marine Habitats 48 Coastal 54 Machair 60 Fen, Marsh and Swamp 66 Lowland Grassland 72 Lowland Heath 78 Lowland Raised Bog 82 Standing Waters 86 Rivers and Streams 92 Woodlands 96 Upland Bogs 102 Upland Fen, Marsh and Swamp 106 Upland Grassland 112 Upland Heathland 118 Upland Inland Rock 124 Montane Habitats 128 Earth Science 134 www.snh.gov.uk i Scottish Natural Heritage Summary Background Scotland has a rich and important diversity of biological and geological features. Many of these species populations, habitats or earth science features are nationally and/ or internationally important and there is a series of nature conservation designations at national (Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)), European (Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protection Area (SPA)) and international (Ramsar) levels which seek to protect the best examples. There are a total of 1881 designated sites in Scotland, although their boundaries sometimes overlap, which host a total of 5437 designated natural features. -

Pres2014-0815.Pdf

m ; THE J©iHIM C^EI^fkl^ f ; £1® IRA1RX ^ CHICAGO o 1 S 1S s ctA-j&f* t a*-* THE ^ HISTORY OF THE SQUIRREL GREAT BRITAIN. J. A. HARVIE-BROWN, F.E.S.E., F.Z.S., MEMBER OF THE BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY M'FARLANE & ERSKINE. 1881. & VvvW1' A. "RrsUiixe. litbo^3Ed.tnburg'h. TEE SQUIKREL IN GEEAT BRITAIN. PAKT I. (Eead 21st April 1880.) GEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE. We,have no evidence of the occurrence of the squirrel in post-tertiary deposits. It is not, I believe, made mention of by Dr James Geikie as being found in post-tertiary deposits in Scotland in his " Great Ice Age." Mr A. Murray, in " The Geographical Distribution of Mammals," tells us : " The only fossil remains of squirrels are of recent date. Remains of the living species of squirrels have been found in bone caves, but nothing indicating its presence in Europe or indeed anywhere else at a more ancient date." Nor does it appear to be of common occurrence even in more recent remains. The only evidence of squirrels in the Pleistocene Shale of Britain is that afforded by gnawed fir-cones in the pre-glacial forest bed of Norfolk, which were recognised by Professor Heer and the late Rev. S. W. King, as I am in¬ formed by Professor Boyd Dawkins, who adds further, that he " does not know of any bones of squirrels in any prehis¬ toric deposit, and I do not think that the nuts (found in marl, etc.) are proved to have been gnawed by them and not by Arvicola amjihitna." I may add here that I have since collected gnawed nuts from various localities and compared them with recent ones, and it seems to me quite impossible to separate them by any evidence afforded by the tooth- marks. -

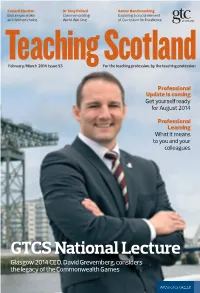

GTCS National Lecture Glasgow 2014 CEO, David Grevemberg, Considers the Legacy of the Commonwealth Games

Council Election Dr Tony Pollard Senior Benchmarking Ensure you make Commemorating Exploring a crucial element an informed choice World War One of Curriculum for Excellence February/March 2014 Issue 53 For the teaching profession, by the teaching profession Professional Update is coming Get yourself ready for August 2014 Professional Learning What it means to you and your colleagues GTCS National Lecture Glasgow 2014 CEO, David Grevemberg, considers the legacy of the Commonwealth Games Teaching Scotland . 3 Are your details up to date? Check on MyGTCS www.teachingscotland.org.uk CONTENTS Teaching Scotland Magazine ~ February/March 2014 EXERCISE YOUR RIGHT TO VOTE David Drever, Convener, GTC Scotland PAGE 14 Contacts GTC Scotland www.gtcs.org.uk [email protected] Customer services: 0131 314 6080 Main switchboard: 0131 314 6000 32 History lessons With The Great Tapestry of Scotland 16 Let the Games begin 36 Professional Learning David Grevemberg, CEO Glasgow 2014, Teacher quality is at the heart vows to empower our young people of the new Professional Update 22 Make your mark 40 Reflective practice Information on candidates for the Dr Bróna Murphy adopts a more Council Election and FE vacancy dialogic approach to reflection 26 Lest we forget 42 How do you measure up? Marking the centenary of the A look at the new Senior Phase start of the First World War Benchmarking Tool 30 Unlocking treasure troves 44 Icelandic adventures Archive experts and teachers are How a visit to Iceland sparked Cherry Please scan this graphic adapting material for today’s lessons Hopton’s love of co-operative learning with your mobile QR code app to go straight 34 Creative Conversations 50 The Last Word to our website Creative Learning Network initiative Dee Matthew, Education Co-ordinator is helping educators share expertise for Show Racism the Red Card “Teachers teach respect and responsibility, discipline, determination, excellence and courage – all really important values” David Grevemberg, CEO, Glasgow 2014, page 16 4 . -

Caithness, Sutherland & Easter Ross Planning

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda Item CAITHNESS, SUTHERLAND & EASTER ROSS PLANNING Report No APPLICATIONS AND REVIEW COMMITTEE – 17 March 2009 07/00448/FULSU Construction and operation of onshore wind development comprising 2 wind turbines (installed capacity 5MW), access track and infrastructure, switchgear control building, anemometer mast and temporary control compound at land on Skelpick Estate 3 km east south east of Bettyhill Report by Area Planning and Building Standards Manager SUMMARY The application is in detail for the erection of a 2 turbine windfarm on land to the east south east of Bettyhill. The turbines have a maximum hub height of 80m and a maximum height to blade tip of 120m, with an individual output of between 2 – 2.5 MW. In addition a 70m anemometer mast is proposed, with up to 2.9km of access tracks. The site does not lie within any areas designated for their natural heritage interests but does lie close to the: • Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands Special Area of Conservation (SAC) • Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands Special Protection Area (SPA) • Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands RAMSAR site • Lochan Buidhe Mires Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) • Armadale Gorge Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) • Kyle of Tongue National Scenic Area (NSA) Three Community Councils have been consulted on the application. Melvich and Tongue Community Councils have not objected, but Bettyhill, Strathnaver and Altnaharra Community Council has objected. There are 46 timeous letters of representation from members of the public, with 8 non- timeous. The application has been advertised as it has been accompanied by an Environmental Statement (ES), being a development which is classified as ‘an EIA development’ as defined by the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations. -

Bettyhill Café and Tourist Information Centre Business Plan 2018

Bettyhill Café and Tourist Information Centre Business Plan 2018 1 | P a g e Executive Summary The Bettyhill Café and Tourist Information Centre is a full-service restaurant/cafe located at the east end of Bettyhill on the A836 adjacent to Strathnaver Museum. The restaurant features a full menu of moderately priced "comfort" food The Bettyhill Café and Tourist Information Centre (TIC) is owned by the Highland Council leased to and operated by Bob and Lindsay Boyle. Strathnaver Museum are undertaking an asset transfer to bring the facility into community ownership as part of the redevelopment of the Strathnaver Museum as a heritage hub for North West Sutherland. This plan offers an opportunity to review our vision and strategic focus, establishing the locality as an informative heritage hub for the gateway to north west Sutherland and beyond including the old province of Strathnaver, Mackay Country and to further benefit from the extremely successful NC500 route. 1 | P a g e Our Aims To successfully complete an asset transfer for a peppercorn sum from the Highland Council and bring the facility into community ownership under the jurisdiction of Strathnaver Museum. To secure technical services to draw appropriate plans for internal rearranging where necessary; to internally redevelop the interior of the building and have the appropriate works carried out. Seek funding to carry out the alterations and alleviate the potential flooding concern. Architecturally, the Café and Tourist Information Centre has not been designed for the current use and has been casually reformed to serve the purpose. To secure a local based franchise operation to continue to provide and develop catering services. -

Fall 2013 NARGS

Rock Garden uar terly � Fall 2013 NARGS to ADVERtISE IN thE QuARtERly CoNtACt [email protected] Let me know what yo think A recent issue of a chapter newsletter had an item entitled “News from NARGS”. There were comments on various issues related to the new NARGS website, not all complimentary, and then it turned to the Quarterly online and raised some points about which I would be very pleased to have your views. “The good news is that all the Quarterlies are online and can easily be dowloaded. The older issues are easy to read except for some rather pale type but this may be the result of scanning. There is amazing information in these older issues. The last three years of the Quarterly are also online but you must be a member to read them. These last issues are on Allen Press’s BrightCopy and I find them harder to read than a pdf file. Also the last issue of the Quarterly has 60 extra pages only available online. Personally I find this objectionable as I prefer all my content in a printed bulletin.” This raises two points: Readability of BrightCopy issues versus PDF issues Do you find the BrightCopy issues as good as the PDF issues? Inclusion of extra material in online editions only. Do you object to having extra material in the online edition which can not be included in the printed edition? Please take a moment to email me with your views Malcolm McGregor <[email protected]> CONTRIBUTORS All illustrations are by the authors of articles unless otherwise stated. -

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015 Proposed CaSPlan The Highland Council Foreword Foreword Foreword to be added after PDI committee meeting The Highland Council Proposed CaSPlan About this Proposed Plan About this Proposed Plan The Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) is the second of three new area local development plans that, along with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and Supplementary Guidance, will form the Highland Council’s Development Plan that guides future development in Highland. The Plan covers the area shown on the Strategy Map on page 3). CaSPlan focuses on where development should and should not occur in the Caithness and Sutherland area over the next 10-20 years. Along the north coast the Pilot Marine Spatial Plan for the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters will also influence what happens in the area. This Proposed Plan is the third stage in the plan preparation process. It has been approved by the Council as its settled view on where and how growth should be delivered in Caithness and Sutherland. However, it is a consultation document which means you can tell us what you think about it. It will be of particular interest to people who live, work or invest in the Caithness and Sutherland area. In preparing this Proposed Plan, the Highland Council have held various consultations. These included the development of a North Highland Onshore Vision to support growth of the marine renewables sector, Charrettes in Wick and Thurso to prepare whole-town visions and a Call for Sites and Ideas, all followed by a Main Issues Report and Additional Sites and Issues consultation. -

Economic Analysis of Strathy North Wind Farm

Economic Analysis of Strathy North Wind Farm A report to SSE Renewables January 2020 Contents 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Introduction 3 3. Economic Impact of Strathy North Wind Farm 6 4. Community Benefit 18 5. Appendix A – Consultations 23 6. Appendix B – Economic Impact Methodology 24 Economic Analysis of Strathy North Wind Farm 1. Executive Summary The development, construction and operation of Strathy North Wind Farm has generated substantial local and national impacts and will continue to do so throughout its operational lifetime and beyond. Strathy North Wind Farm, which is based in the north of Scotland, near Strathy in North Sutherland, was developed and built at a cost of £113 million (DEVEX/CAPEX). Operational expenditure (OPEX) and decommissioning costs over its 25-year lifetime are expected to be £121 million. The expected total expenditure (TOTEX) is £234 million. During the development and construction of Strathy North Wind Farm, it was estimated that companies and organisations in Scotland secured contracts worth £59.4 million. The area is expected to secure £100.6 million in OPEX contracts over the wind farm’s operational lifetime (£4.0 million annually). Overall the expenditure, including decommissioning, secured in Scotland is expected to be £165.0 million, or 73% of TOTEX. Highland is expected to secure £21.9 million in DEVEX/CAPEX contracts and £51.5 million in OPEX contracts (£2.1 million annually). Overall, Highland is expected to secure contracts worth £77.0 million, or 33% of TOTEX. Of this, £25.6 million, equivalent to 11% of TOTEX is expected to be secure in Caithness and North Sutherland. -

Western Naturalist

I The Western Naturalist Volume Four 7975 / Annual Subscription £3.00 A Journal of Scottish Natural History THE WESTERN NATURALIST A Journal of Scottish Natural History- Editorial Committee: Dr. J.A. Gibson Dr. John Hamilton Professor J.C. Smyth DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY, PAISLEY COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY, HIGH STREET, PAISLEY The Western Naturalist is a.n independent journal, published by the RENFREWSHIRE NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY, devoted to the study of Scottish natural history, particularly, but not exclus- ively, to the natural history of the Western area. Although its main interests probably centre on fauna and flora it is prepared to publish articles on the many aspects embraced by its title including Zoology, Botany, History, Environment, Geology, Archae- ology, Geography etc. All articles and notes for publication, books for review etc, should be sent to the Editors at the DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY, PAISLEY COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY, HIGH STREET, PAISLEY. Contributions should be clearly written; whenever possible they should be typed, double-spaced, on one side of the paper, with adequate margins, and should try to conform to the general style and arrangement of articles and notes in the current number of the journal. Maps, diagrams and graphs should be drawn in black ink on white unlined paper. Photographs should be on glossy paper. Proofs of all articles will be sent to authors and should be returned without delay. Authors of articles, but not of short notes, will receive thirty reprints in covers free of charge. Additional copies may be ordered, at cost, when the proofs are returned. The Western Naturalist will be published annually, and more often as required.