Pres2014-0815.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

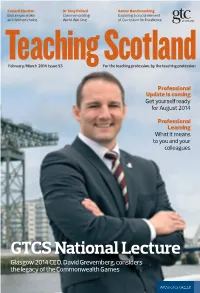

GTCS National Lecture Glasgow 2014 CEO, David Grevemberg, Considers the Legacy of the Commonwealth Games

Council Election Dr Tony Pollard Senior Benchmarking Ensure you make Commemorating Exploring a crucial element an informed choice World War One of Curriculum for Excellence February/March 2014 Issue 53 For the teaching profession, by the teaching profession Professional Update is coming Get yourself ready for August 2014 Professional Learning What it means to you and your colleagues GTCS National Lecture Glasgow 2014 CEO, David Grevemberg, considers the legacy of the Commonwealth Games Teaching Scotland . 3 Are your details up to date? Check on MyGTCS www.teachingscotland.org.uk CONTENTS Teaching Scotland Magazine ~ February/March 2014 EXERCISE YOUR RIGHT TO VOTE David Drever, Convener, GTC Scotland PAGE 14 Contacts GTC Scotland www.gtcs.org.uk [email protected] Customer services: 0131 314 6080 Main switchboard: 0131 314 6000 32 History lessons With The Great Tapestry of Scotland 16 Let the Games begin 36 Professional Learning David Grevemberg, CEO Glasgow 2014, Teacher quality is at the heart vows to empower our young people of the new Professional Update 22 Make your mark 40 Reflective practice Information on candidates for the Dr Bróna Murphy adopts a more Council Election and FE vacancy dialogic approach to reflection 26 Lest we forget 42 How do you measure up? Marking the centenary of the A look at the new Senior Phase start of the First World War Benchmarking Tool 30 Unlocking treasure troves 44 Icelandic adventures Archive experts and teachers are How a visit to Iceland sparked Cherry Please scan this graphic adapting material for today’s lessons Hopton’s love of co-operative learning with your mobile QR code app to go straight 34 Creative Conversations 50 The Last Word to our website Creative Learning Network initiative Dee Matthew, Education Co-ordinator is helping educators share expertise for Show Racism the Red Card “Teachers teach respect and responsibility, discipline, determination, excellence and courage – all really important values” David Grevemberg, CEO, Glasgow 2014, page 16 4 . -

Tartans: Scotland’S National Emblem

ESTABLISHED IN 1863 Volume 149, No. 3 November 2011 TARTANS: SCOTLAND’S NATIONAL EMBLEM Tartan has without doubt become one of the most important sym- Inside this Issue bols of Scotland and Scottish Heritage and with the Scots National Feature Article…….….....1 identity probably greater than at any time in recent centuries, the po- Message from our tency of Tartan as a symbol cannot be understated. However, it has President….......................2 also created a great deal of romantic fabrication, controversy and Upcoming Events…….....3 speculation into its origins! name, history and usage as a Clan or Family form of identification. The Chicago Fire and The Celebration of St. An‐ drewʹs Day .……….……4 Gifts to the Society……...8 Flowers of the For‐ est……………..…..…….9 BBC Alba Scottish Tradi‐ tional Music Awards…..10 Banquet & Ball….….12‐15 Tartan is a woven material, generally of wool, having stripes of different colors and varying in breadth. The arrangement of colors is alike in warp and weft ‐ that is, in length and width ‐ and when woven, has the appearance of being a number of squares intersected by stripes which cross each other; this is called a ‘sett’. By changing the colors; varying the width; depth; number of stripes, differenc‐ (Continued on page 4) November 2011 www.saintandrewssociety‐sf.org Page 1 A Message from Our President The Saint Andrew's Dear Members and Society Society of San Francisco Friends: 1088 Green Street San Francisco, CA The nominating committee met to 94133‐3604 (415) 885‐6644 select Society Officers to serve for Editor: William Jaggers 2012. -

Scottish Missionaries and the Circumcision Controversy in Kenya 1900-1960

International Review of Scottish Studies Vol. 28 2003 Kenneth Mufaka SCOTTISH MISSIONARIES AND THE CIRCUMCISION CONTROVERSY IN KENYA 1900-1960 t the turn of the century, the British High Commis- sioner in East Africa set up various areas in which A Christian missionaries were allowed exclusive influence. Scottish missionaries served the largest and most politically astute tribe in Kenya, the Kikuyu. Scottish educa- tion, combining a theoretical base with vocational training, attracted the best and the brightest of Kikuyu youths. This type of education provided a basis for future employment in government and industry. Jomo Kenyatta and Mbui Koinanage, both future nationalist leaders of Kenya, were converts and protégés of Scottish missionaries. However, in 1929, a sudden rift occurred between the Kikuyu Christian elders and congregations on one hand and their Scottish missionary patrons on the other side. The rift came about when the Scottish missionaries insisted that all Kikuyu Christians should take an oath against female initiation. Two thirds of the Kikuyu Christians left the mission church to form their own nationalist oriented churches. The rise of nationalistic feeling among Kenyans can be traced to this controversy. The issue of female circum- cision seems to have touched on all the major ingredients that formed the basis of African nationalist alienation from colo- nial rule. This article argues that the drama of 1929 was a rehearsal of the larger drama of the Mau Mau in 1950-1960 that put an end to colonial rule in Kenya. Though initiation practices were widespread in Kenya and the neighboring Sudan, the Scottish missionaries were unaware of them until 1904. -

Western Naturalist

I The Western Naturalist Volume Four 7975 / Annual Subscription £3.00 A Journal of Scottish Natural History THE WESTERN NATURALIST A Journal of Scottish Natural History- Editorial Committee: Dr. J.A. Gibson Dr. John Hamilton Professor J.C. Smyth DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY, PAISLEY COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY, HIGH STREET, PAISLEY The Western Naturalist is a.n independent journal, published by the RENFREWSHIRE NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY, devoted to the study of Scottish natural history, particularly, but not exclus- ively, to the natural history of the Western area. Although its main interests probably centre on fauna and flora it is prepared to publish articles on the many aspects embraced by its title including Zoology, Botany, History, Environment, Geology, Archae- ology, Geography etc. All articles and notes for publication, books for review etc, should be sent to the Editors at the DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY, PAISLEY COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY, HIGH STREET, PAISLEY. Contributions should be clearly written; whenever possible they should be typed, double-spaced, on one side of the paper, with adequate margins, and should try to conform to the general style and arrangement of articles and notes in the current number of the journal. Maps, diagrams and graphs should be drawn in black ink on white unlined paper. Photographs should be on glossy paper. Proofs of all articles will be sent to authors and should be returned without delay. Authors of articles, but not of short notes, will receive thirty reprints in covers free of charge. Additional copies may be ordered, at cost, when the proofs are returned. The Western Naturalist will be published annually, and more often as required. -

174 PROCEEDINGS of the SOCIETY, FEBRUARY 8, 1937. II. W. J. Mccallien, D.Sc

174 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, FEBRUARY 8, 1937. II. LATE-GLACIA EARLD AN L Y POST-GLACIAL SCOTLANDY B . W . J McCALLIEN. , D.Sc., F.R.S.E., GLASGOW UNIVERSITY. I. INTRODUCTION. It is unnecessary for the writer to emphasise the interdependence of the two sciences, Geology and Prehistory. It is well known that e geologisth s dependeni t e archaeologisth n e interpretatioo tth r fo t n e fossilsoth f e theb , y human remain r implementso s ,r founou n i d superficial deposits d thaan ,t geological method e constantlar s y used archaeologiste th y b . Nevertheless face spitn th i ,t f ethao t everybody realises that this interdependence theoretically exists, it is remarkable how seldom marke y theran s ei d co-operation betwee e workernth n i s these two fields. This is perhaps particularly so in Scotland. remaine r earlTh ou yf so ancestor s come withi sphere nth geologf eo y e fossie studth th f ls o y a remaine samy th ewa n f i ancien o s t plants animald an e everyda s parth i s f o t ye geologist tasth f ko . Geologs yi concerned with the history of the earth, of its fauna and flora. The geologist doe t thin no sf stoppin o k s researcheghi y timan e t a befors e e presenth s jus i ts activ a daye t H e. watchin e actiogth f mano n , or of the sea, or of the rivers of to-day, as he is in unravelling the history of a thousand million years ago when our oldest rocks were being formed. -

Disingenuous Information About Clan Mactavish (The Clan Tavish Is an Ancient Highland Clan)

DISINGENUOUS INFORMATION ABOUT CLAN MACTAVISH (THE CLAN TAVISH IS AN ANCIENT HIGHLAND CLAN) BY PATRICK L. THOMPSON, CLAN MACTAVISH SEANNACHIE COPYRIGHT © 2018, PATRICK L. THOMPSON THIS DOCUMENT MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED, COPIED, OR STORED ON ANY OTHER SYSTEM WHATSOEVER, WITHOUT THE EXPRESSED WRITTEN PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR. SANCTIONED CLAN MACTAVISH SOCIETIES OR THEIR MEMBERS MAY REPRODUCE AND USE THIS DOCUMENT WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR. The more proper title of the clan is CLAN TAVISH (Scottish Gaelic: Clann Tamhais ), but it is commonly known as CLAN MACTAVISH (Scottish Gaelic: Clann MacTamhais ). The amount of disingenuous information found on the internet about Clan MacTavish is AMAZING! This document is meant to provide a clearer and truthful understanding of Clan MacTavish and its stature as recorded historically in Scotland. Certain statements/allegations made about Clan MacTavish will be addressed individually. Disingenuous statement 1: Thom(p)son is not MacTavish. That statement is extremely misleading. The Clans, Septs, and Regiments of the Scottish Highlands (CSRSH), 8th Edition, 1984, pp. 301, 554, Frank Adam, revised by Lord Lyon Sir Thomas Innes of Learney, states: pg. 111 Date of the 8th Edition of CSRSH is 1984, and pages 331 & 554 therein reflects that MacTavish is a clan, and that Thompson and Thomson are MacTavish septs. It does not say that ALL Thom(p)sons are of Clan MacTavish; as that would be a totally false assumption. Providing a reference footnote was the most expedient method to correct a long-held belief that MacTavish was a sept of Campbell, without reformatting the pages in this section. -

Environmental and Ecological Readings: Nature, Human and Posthuman Dimensions in Scotland

Environmental and Ecological Readings in Scotland p. 11-21 Environmental and Ecological Readings: Nature, Human and Posthuman Dimensions in Scotland. Introduction Philippe Laplace And then a queer thought came to her there in the drookèd fields, that nothing endured at all, nothing but the land she passed across, tossed and turned and perpetually changed below the hands of the crofter folk since the oldest of them had set the Standing Stones by the loch of Blawearie and climbed there on their holy days and saw their terraced crops ride brave in the wind and sun. Sea and sky and the folk who wrote and fought and were learnéd, teaching and saying and praying, they lasted but as a breath, a mist of fog in the hills, but the land was forever, it moved and changed below you, but was forever, you were close to it and it to you, not at a bleak remove it held you and hurted you. And she had thought to leave it all!1 Ecopoetics and nature narrative have been at the forefront of literary studies since Jonathan Bate’s landmark essay on ecocriticism in 1991. Growing concerns with the environment and the impact of human activity on the future of the planet have also fed this narrative practice and its critical analysis. Louisa Gairn has fostered these concepts in a Scottish context; by studying how, since the nineteenth century, poets and novelists have brought nature and the environment into play in their works, she has convincingly demonstrated how relevant they are for Scottish authors and the Scottish literary tradition.2 1 Lewis Grassic Gibbon, Sunset Song (1932; Edinburgh: Canongate Classics, 1999), p. -

Heraldic Arms and Badges

the baronies of Duffus, Petty, Balvenie, Clan Heraldic Arms and Aberdour in the northeast of Murray Clan On 15 May 1990 the Court of Lord Scotland, as well as the lordships of Lyon granted The Murray Clan Society Bothwell and Drumsargard and a our armorial ensign or heraldic arms. An Society number of other baronies in lower armorial ensign is the design carried on Clydesdale. Sir Archibald, per the a flag or shield. English property law of jure uxoris, Latin for "by right of (his) wife" became the The Society arms are described on th th Clan Badges legal possessor of her lands. the 14 page of the 75 Volume of Our Public Register of All Arms and Bearings and Heraldic Which Crest Badge to Wear in Scotland, VIDELICT as: Azure, five Although Murrays were permitted to annulets conjoined in fess Argent wear either the mermaid or demi-man between three mullets of the Last. Above Arms crest badges, sometime in the late the Shield is placed an Helm suitable to Clan Badges 1960’s or early 1970’s, the Lord Lyon an incorporation (VIDELICET: a Sallet Prior to the advent of heraldry, King of Arms declared the demi-man Proper lined Scottish clansmen and clanswomen crest badge inappropriate. Since his Gules) with a wore badges to identify themselves. decisions on heraldic matters have the Clan badges were devices with family or force of law in Scotland, all the personal associations which identified manufacturers of clan badges, etc., the possessor, not unlike our modern ceased producing the demi-man. There class rings, military insignias, union pins, was a considerable amount of feeling on etc. -

Heraldry: Where Art and Family History Meet Part II: Marshalling and Cadency by Richard A

Heraldry: Where Art and Family History Meet Part II: Marshalling and Cadency by Richard A. McFarlane, J.D., Ph.D. Heraldry: Where Art and Family History Meet 1 Part II: Marshalling and Cadency © Richard A. McFarlane (2015) Marshalling is — 1 Marshalling is the combining of multiple coats of arms into one achievement to show decent from multiple armigerous families, marriage between two armigerous families, or holding an office. Marshalling is accomplished in one of three ways: dimidiation, impalement, and 1 Image: The arms of Edward William Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. Blazon: Quarterly: 1st, Gules a Bend between six Cross Crosslets fitchée Argent, on the bend (as an Honourable Augmentation) an Escutcheon Or charged with a Demi-Lion rampant pierced through the mouth by an Arrow within a Double Tressure flory counter-flory of the first (Howard); 2nd, Gules three Lions passant guardant in pale Or in chief a Label of three points Argent (Plantagenet of Norfolk); 3rd, Checky Or and Azure (Warren); 4th, Gules a Lion rampant Or (Fitzalan); behind the shield two gold batons in saltire, enamelled at the ends Sable (as Earl Marshal). Crests: 1st, issuant from a Ducal Coronet Or a Pair of Wings Gules each charged with a Bend between six Cross Crosslets fitchée Argent (Howard); 2nd, on a Chapeau Gules turned up Ermine a Lion statant guardant with tail extended Or ducally gorged Argent (Plantagenet of Norfolk); 3rd, on a Mount Vert a Horse passant Argent holding in his mouth a Slip of Oak Vert fructed proper (Fitzalan) Supporters: Dexter: a Lion Argent; Sinister: a Horse Argent holding in his mouth a Slip of Oak Vert fructed proper. -

Introduction to Scottish Heraldry Viscount Dunrossil Chairman, Society of Scottish Armigers

Introduction to Scottish Heraldry Viscount Dunrossil Chairman, Society of Scottish Armigers Saturday, January 26, 13 Why should we care? • 1. Illustrated, colorful history • 2. As Scots at Games etc. we use it all the time, on clan badges, cofee mugs, jewelry etc. Might as well get it right and know what we’re doing. • 3. Part of everyday life even for non- Scots, of what many men in particular care most about Saturday, January 26, 13 Sports rivalries Saturday, January 26, 13 Saturday, January 26, 13 Arms of City of Manchester Saturday, January 26, 13 Elements of heraldry in sports • Shield, design e.g. Dallas Cowboys’ Star • Color: crimson tide, burnt orange, maize and blue • Supporters in livery! • Motto, slogan: Roll Tide, Superbia in Proelio Saturday, January 26, 13 Historical origins • Knights in battle, craving distinction, honor, in classic “shame culture” • Jousting competition: need for recognition. • Role of heralds evolving from messengers to introductions to keepers of logs and registers to arbiters and granters of arms. Saturday, January 26, 13 The Lord Lyon King of Arms • England has three (Garter, Clarenceaux and Norroy and Ulster), Scotland just one King of Arms, one ultimate authority • Unlike English Kings of Arms, who need permission from Earl Marshall, Lyon can grant arms himself • Keeps Public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland • Junior ofcer of State. Judge with own court and right to rule on all matters relating to Scottish heraldry, impose fines, imprison etc. Saturday, January 26, 13 Arms of Lyon Sellar -

PO Box 191 Launceston Tasmania 7250 State Secretary: [email protected] Home Page

TASMANIAN FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY INC. PO Box 191 Launceston Tasmania 7250 State Secretary: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.tasfhs.org Patron: Dr Alison Alexander Fellows: Neil Chick, David Harris and Denise McNeice Executive: President Peter Cocker (03) 6435 4103 Vice President Denise McNeice FTFHS (03) 6228 3564 Vice President Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Executive Secretary Miss Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Executive Treasurer Miss Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Committee: Judy Cocker Rosemary Davidson John Gillham Libby Gillham David Harris FTFHS Isobel Harris Beverley Richardson Helen Stuart Judith Whish-Wilson By-laws Officer Denise McNeice FTFHS (03) 6228 3564 eHeritage Coordinator Peter Cocker (03) 6435 4103 Exchange Journal Coordinator Thelma McKay (03) 6229 3149 Home Page (State) Webmaster Peter Cocker (03) 6435 4103 Journal Editor Leonie Mickleborough (03) 6223 7948 Journal Despatcher Leo Prior (03) 6228 5057 LWFHA Coordinator Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Members’ Interests Compiler John Gillham (03) 6239 6529 Membership Registrar Judy Cocker (03) 6435 4103 Projects & Publications Coord. Rosemary Davidson (03) 6278 2464 Public Officer Denise McNeice FTFHS (03) 6228 3564 Reg Gen BDM Liaison Officer Colleen Read (03) 6244 4527 Research Coordinator Mrs Kaye Stewart (03) 6362 2073 State Sales Officer Mrs Pat Harris (03) 6344 3951 Branches of the Society Burnie: PO Box 748 Burnie Tasmania 7320 [email protected] Devonport: PO Box 587 Devonport Tasmania 7310 [email protected] Hobart: PO Box 326 Rosny Park Tasmania 7018 [email protected] Huon: PO Box 117 Huonville Tasmania 7109 [email protected] Launceston: PO Box 1290 Launceston Tasmania 7250 [email protected] Volume 24 Number 4 March 2004 ISSN 0159 0677 Contents Editorial ..................................................................................................................... -

The Galley in Scottish Heraldry

The Galley in Scottish Heraldry In the 12th Century, Viking power over the Hebrides was waning. For 400 years their longships had prevailed along the coastlines, at first raiding and pillaging, then carrying on campaigns, gradually becoming more and more comfortable as seems inevitable with empires until they discover that their power has been usurped by a more aggressive force. In this case, the force was Somerled, an Irish-Scots warrior with exceptional ability matched only by his ambition. Somerled is one of those characters who really add colour to history. In 1156 he and his sons, Doughall, Reginald and Angus managed to smash a fleet of 80 Viking longships off the coast of the Isle of Islay. Within 2 years he was strong enough to assume the title of Rex Insularum, King of the Isles, claiming sovereignty over 25,000 square miles and 500 islands. Somerled was assassinated in 1164 as he prepared to battle King Malcolm of the Scots, whereupon his lands were divided between his three sons, Reginald becoming heir to the title of King or Lord of the Isles. Reginald's son Donald succeeded him and so the Clan MacDonald was founded. The title was held by successive generations of MacDonalds until 1476 when John of Islay made an object submission to the Scottish king and was stripped of most of his lands. His son Angus, disgusted at this weakness, defeated his father in a galley battle in Bloody Bay just north of Tobermory about 5 years later. Angus' supremacy was short-lived as he was stabbed to death by a Harper in 1490.