Leeds Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

016 Market Study with Focus on Potential for Eu High-Tech Solution Providers

Co-funded by MALAYSIA’S TRANSPORT & INFRASTRUCTURE SECTOR 2016 MARKET STUDY WITH FOCUS ON POTENTIAL FOR EU HIGH-TECH SOLUTION PROVIDERS Market Report 2016 Implemented By SEBSEAM-MSupport for European Business in South East Asia Markets Malaysia Component Publisher: EU-Malaysia Chamber of Commerce and Industry (EUMCCI) Suite 10.01, Level 10, Menara Atlan, 161B Jalan Ampang, 50450 Kuala Lumpu Malaysia Telephone : +603-2162 6298 r. Fax : +603-2162 6198 E-mail : [email protected] www.eumcci.com Author: Malaysian-German Chamber of Commerce and Industry (MGCC) www.malaysia.ahk.de Status: May 2016 Disclaimer: ‘This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the EU-Malaysia Chamber of Commerce and Industry (EUMCCI) and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union’. Copyright©2016 EU-Malaysia Chamber of Commerce and Industry. All Rights Reserved. EUMCCI is a Non-Profit Organization registered in Malaysia with number 263470-U. Privacy Policy can be found here: http://www.eumcci.com/privacy-policy. Malaysia’s Transport & Infrastructure Sector 2016 Executive Summary This study provides insights into the transport and infrastructure sector in Malaysia and identifies potentials and challenges of European high-technology service providers in the market and outlines the current situation and latest development in the transport and infrastructure sector. Furthermore, it includes government strategies and initiatives, detailed descriptions of the role of public and private sectors, the legal framework, as well as present, ongoing and future projects. The applied secondary research to collect data and information has been extended with extensive primary research through interviews with several government agencies and industry players to provide further insights into the sector. -

First Record of the Rough-Necked Monitor Varanus Rudicollis from Penang, Malaysia

Biawak, 6(2), pp. 78 © 2012 by International Varanid Interest Group First Record of the Rough-necked Monitor Varanus rudicollis from Penang, Malaysia RAY HAMILTON E-mail: [email protected] Abstract - Varanus rudicollis is recorded from the island of Penang, Malaysia for the first time. In Malaysia, the known distribution of the from a slight adjustment of its upper body position, the rough-necked monitor Varanus rudicollis is poorly lizard was apparently unconcerned by our presence documented, with relatively few reliable localities nearby. The canopy walkway from which the observation scattered throughout Borneo and Peninsular Malaysia was made is located at the edge of a developed area (Bennett & Liat, 1995). As far as it can be determined, bordered by dense forest, with mature trees and thick there are no records of its occurrence on the island of vegetation. The Penang Hill Canopy Walkway is located Penang, Malaysia. 1.7 km from the upper Penang Hill Railway Station, at On 29 April 2008, a single specimen of V. rudicollis an approximate elevation of 710 m above sea level at the was observed and photographed on the island of Penang, summit of Penang Hill (Bukit Bendera), Malaysia (5° Malaysia (Figs. 1 & 2). The sub-adult lizard was seen 25 ̍ 46.38 ̎ N; 100° 16 ̍ 3.68 ̎ E). during mid-afternoon at rest in a tree, approximately 10 m off the ground. The lizard remained at rest in the same References position during the ten minutes under observation. Apart Bennett, D. & L.B. Liat. 1995. A note on the distribution of Varanus dumerilii and V. -

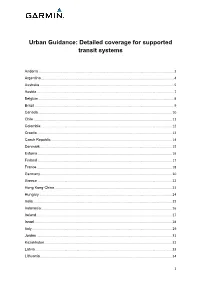

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................. -

Pf Revised 050309.Qxd

Penang Forum Report of Working Groups Local Government Youth and Students The Arts Labour Health Heritage Women Goodwill Initiatives Transport Persons with Disabilities Environment Penang Forum first met in April 2008 at a general public forum held at Disted College, Penang. Eleven working groups were set up, charged to make recommendations to the new state government. These are their reports. This Report has been produced by the combined efforts of the Penang Forum participants, who adopted the Declaration contained on page 5, and all the working group members. copyright: December 2008 Table of Contents Table Table of Contents The Declaration of the Penang Forum 5 (statement of principles) Reports and Recommendations of Working Groups on Local Government 6 Labour 13 Women 20 Persons with Disabilities 25 Youth and Students 30 Health 33 Goodwill Initiatives (intercultural relations) 36 The Environment 38 The Arts 45 Heritage 57 Transport 60 The recommendations are based on the reports of 11 different working groups, which were set up following the public Penang Forum, held at Disted College on April 13th 2008 . The Forum and the reports of the subsequent working groups do not claim to be comprehensive. For example, they do not cover the more macro issues of economy and poverty. A second Forum is planned to discuss these. Nevertheless, crucial issues are covered in the reports, and we sincerely hope that the Penang State Government and its members pay due attention to the recommendations which they contain. Together we can make a positive difference for the future of Penang. Penang Forum Working Group Reports 2008 ToC Preface state government official. -

Newsletter 97.Indd

Newsletter Issue 97 /March 2010 Support Conservation Efforts in Your Community! 26 Church Street, City of George Town, 10200 Penang, Malaysia Tel: 604-2642631 | Fax: 604-2628421 Email: [email protected] | Website: www.pht.org.my Editorial Penang Hill Railway In this issue of the Newsle e r we unabashedly celebrate Penang’s funicular railway while lament- ing the shortsighted decision to dismantle this major heritage asset that has been identi ed worldwide with Penang for almost ninety years. Since the closure of the Penang Hill Railway in late Febru- ary the mainstream media have published a stream of le ers om people in Malaysia and abroad making it clear that scrapping the historic railway will destroy a unique a raction that has drawn tourists not only o m Malaysia and the region but om all over the world. One foreign tourist sug- gested that destroying the historic The Star 22 February 2010 funicular would be like San Francisco abolishing its famous trams. As a measure of the value of the Penang Hill Railway there has even been an indication of interest in acquiring some of the specialized equipment and machinery for use in restoring an historic funicular railway in Europe. i s would be akin to ge ing rid of the family silver because we are buying new stainless steel cutlery. In anticipation of the closure of the railway, the Penang Heritage Trust decided on a farewell trip on the his- toric funicular for its monthly site visit in February. e result was a record turn-out of almost ninety PHT members and iends for a nostalgic and unforge able a ernoon in February that included an informative and magical visit to the winding-engine house at Upper Station. -

A Paradigm Shift in Foreign Tourist Arrivals – the Imperative for Penang Hill’S Sustainable Growth

A PARADIGM SHIFT IN FOREIGN TOURIST ARRIVALS – THE IMPERATIVE FOR PENANG HILL’S SUSTAINABLE GROWTH BY SUKUMARAN SUMMUGAM Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MBA (Service Science, Management and Engineering) June 2015 Acknowledgement Foremost, I am grateful to the God for the good health and wellbeing that were necessary to complete this Case Study for my MBA SSME program. I wish to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Tan Cheng Ling, my project supervisor, for her continuous support, for her patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. Her guidance helped me in all the time of research and writing of this case study. I place my record, my sincere thank you to Associate Prof. Dr. Sofri Yahya, Dean of Graduate School of Business (GSB), University Sains Malaysia, for providing all the necessary exposure , opportunities and facilities for the program. I am also grateful to Dr. Rosly Othman, the Program Manager for MBA and Dr. Salmi Mohd. Isa, the Senior Lecturer in GSB. I am extremely thankful and indebted to them for sharing their expertise, sincere and valuable guidance and encouragement extended to me. I take this opportunity to express gratitude to all of the GSB members for their help and support. I also thank my parents for their encouragement and blessings and my special thanks goes to my wife for standing by me during all the testing times and to give the courage to withstand against them, my wonderful children for their understanding, patient and support. I also place on record, my sense of gratitude to one and all, who directly or indirectly, have lent their hand in this venture. -

Economy of Malaysia Pdf

Economy of malaysia pdf Continue Malaysia's economyKuala Lumpur, the national capital of Malaysia, and its largest cityCurrencyRinggit (MYR, RM)Financial yearKalendar yearAPEC, ASEAN, IOR-ARC, WTOCountry Development Group/Emerging 1 Top-Middle Income Economics (2) StatisticsPopulation 31.528.585 (2018) $900 billion (PPP, 2020) GDP ranked 39th (nominal, 2020) 25th (PPP, 2020)) GDP growth of 4.7% (2018) 4.3% (2019) 3.1% (2020f) 6.9% (2021f) GDP per capita $10,192 (nominal, 2020) $27,287 (PPP, 2020 est.. GDP by agriculture: 7.1% industry: 36.8% services: 56.2% (2016) Inflation (CPI) - 1.1% (2020) [4] Население за чертой бедности 15% (2019 г.) 2,7% менее чем на $5,50/день (2015 г.) Всемирный банк) Индекс развития человека 0.804 очень высок (2018) (61-е место) N/A IHDI (2018) 2 (2019 г.) - 66,1% занятости (2018 г.) Рабочая сила по профессии сельского хозяйства: 11,1% промышленности: 36% услуг: 53% (2012 г.) Безработица 3,4% (июнь 2017 г.) полупроводники, микрочипы, интегрированные схемы, резина, олеохимические, автомобильные, оптические приборы, фармацевтические препараты, медицинское оборудование, плавка, древесина, древесная целлюлоза, исламские финансы, нефть, ликуированный природный газ, нефтехимия, телекоммуникационный продуктEase-of-doing-business занимают 12-е место (очень легко, 2020) [17] Экспортные товарыСемипроводор - электронная продукция, пальмовое масло, сжиженный природный газ, нефть, химикаты, машины, транспортные средства, оптическое и научное оборудование, производство металла, каучука, древесины и древесной продукцииМаин -

Application of Public-Private Partnership Concept in a Tourism Destination: a Case Study of Penang Hill

APPLICATION OF PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP CONCEPT IN A TOURISM DESTINATION: A CASE STUDY OF PENANG HILL MOHD FIRDAUS BIN HABIB MOHD UNIVERSITI SAINS MALAYSIA 2018 APPLICATION OF PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP CONCEPT IN A TOURISM DESTINATION: A CASE STUDY OF PENANG HILL by MOHD FIRDAUS BIN HABIB MOHD Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Alhamdulillah to Almighty Allah and Rasulullah (pbuh) for giving me the strength, courage, patience and inspiration to finish writing this dissertation. I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my parents, Zubytha binti Majid and Habib Mohd bin Mohamed Sha and my younger sister, Noor Hayati and brother-in-law, Nor Izzudin, who sacrificed so much for me throughout the duration of my study. I am also very grateful and wish to thank my main supervisor, Professor Chan Ngai Weng, for his guidance and supervision throughout my candidature in Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM). My gratitude also extends to Professor Suriati Ghazali, Professor Badaruddin Mohamed and Professor Amran Hamzah for their invaluable inputs and advice in improving this thesis. I wish to thank Dr Mohamed Amiruddin Fawzi Bahaudin, Associate Professor Dr Azizan Marzuki and colleagues in Politeknik Sultan Abdul Halim Mu’adzam Shah (POLIMAS) for their advice, assistance and support. I wish to also extend my gratitude to the Dean and the staffs of the School of Humanities USM for providing me with the research facilities. To friends, especially Faizul, Mastura, Ratna, Faezah, Jaspal, Mages, Sofiyah, and Fairuz, I wish to convey my gratitude for their generous support throughout the duration of my study. -

Penang Beyond Meetings for India Market

Penang: Experiences Unfiltered Penang is a tropical paradise that not only boasts beautiful beaches and lush rainforests, but also the UNESCO World Heritage Site of George Town. Centuries of heritage, gorgeous colonial and pre-war architecture, an active arts and festivals scene, world famous gastronomic culture is all juxtaposed against the backdrop of an international city. We welcome you to step beyond meetings and indulge in Penang’s infinite Experiences Unfiltered! The Penang Factor Known as one of the world’s must-visit destinations, Penang never ceases to amaze its guests who experience its raw beauty through its vibrant cultural diversity and fusion of old and new. Here are six reasons why Penang should be your Business Events destination of choice. Bucket List Destination Heritage and Culture Capital Penang is on many savvy travellers’ bucket list, Penang is bursting at the seams with heritage and constantly making media headlines around the culture! George Town was awarded a UNESCO world as a must-visit destination. Biggest factor heritage site status in 2008 as a living museum, being a tropical destination that delivers an all-round as it represents the most complete surviving Asian cultural and heritage experience and assures historic city centre in Asia with a multi-cultural living all modern comforts at the same time. Hotels heritage originating from its trade routes. Every and resorts are abundant in Penang. From luxury possible traditional or modern entertainment is hotels to quaint heritage boutique hotels within the available locally throughout the year to keep your UNESCO world heritage city zones; Penang will delegates on their toes all day and night. -

A Preferred Cruise Destination

Philippines Thailand South China Sea Straits of Malacca MALAYSIA Brunei Darussalam Kuala Lumpur Langkawi Star Cruise Jetty, Langkawi Singapore PERLIS Thailand Swettenham Pier Cruise Terminal, A Preferred Cruise George Town Indonesia Langkawi Kangar Langkawi International Airport Alor Setar Kota Bharu Pulau Redang Port, Pulau Perhentian Pulau Redang Payar KEDAH Pulau Redang Destination PENANG George Town Cruise Ports in Kuala Terengganu Penang KELANTAN International PERAK Airport TERENGGANU Malaysia Ipoh SULU SEA Taman Negara Cameron Highlands Pulau Pangkor Pulau Pangkor Laut Kota Kinabalu Port, PAHANG Kota Kinabalu STRAITS OF MALACCA Fraser’s Hill Kuantan Tunku Abdul Rahman Park Berjaya Hills Kuantan Port, Genting Highlands Kuantan Kota Kinabalu International SELANGOR Airport Sandakan Subang Kota Kuala Lumpur Tioman Port, Kinabalu Shah Alam Pulau Tioman Putrajaya SOUTH CHINA Kinabalu Park Boustead Cruise Centre, SEA NEGERI Pulau Tioman Labuan Port Klang KLIA 2 SEMBILAN Seremban Pulau SABAH Lahad Datu Kuala Lumpur International Rawa Brunei Airport (KLIA) MELAKA Darussalam Lawas Melaka City JOHOR Pulau Sibu Limbang Tawau Senai International Airport Miri Melaka Marina, Melaka City Pulau Mabul Pulau Sipadan Johor Bahru Mulu National Park Singapore Bintulu Port, Bintulu Bintulu CELEBES SEA Kuching Port, Kuching Sibu SARAWAK Tanjung Manis LEGEND Capital City International Airport Ports Kuching Federal Territory Domestic Airport State Capital Marine Park Kuching Glossary International State Border Highland Resort Airport Pulau - Island Indonesia International Border National Park Gunung - Mountain * Map not drawn to scale www.facebook.com/friendofmalaysia twitter.com/tourismmalaysia Published by Tourism Malaysia, Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Malaysia ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in whole or part without the written permission of the publisher. -

Study on the Development of Hill Stations Final Report II

Study on the Development of Hill Stations Final Report II TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS..........................................................................................i LIST OF TABLES..................................................................................................iv LIST OF FIGURES AND PLATES .......................................................................vi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.....................................................................................E-1 LIST OF ACTION PLANS...................................................................................A-1 CHAPTER 1 : INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 STUDY OBJECTIVES................................................................................. 1-2 1.3 STUDY APPROACH................................................................................... 1-2 1.4 STUDY AREA ............................................................................................. 1-3 1.5 CONCEPT OF CARRYING CAPACITY ..................................................... 1-4 1.6 FORMAT OF REPORT ............................................................................... 1-5 CHAPTER 2 : PENANG HILL 2.1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 EXISTING SITUATION .............................................................................. -

On Passenger Transportation

ROYAL MALAYSIAN CUSTOMS GOODS AND SERVICES TAX GUIDE ON PASSENGER TRANSPORTATION GUIDE ON PASSENGER TRANSPORTATION As at 26 APRIL 2015 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 Overview of Goods and Services Tax (GST) .......................................................... 1 GENERAL OPERATIONS OF THE INDUSTRY ........................................................ 1 Overview of passenger transportation .................................................................... 1 GST TREATMENT FOR PASSENGER TRANSPORTATION .................................. 2 Domestic passenger transportation ........................................................................ 2 International passenger transportation ................................................................... 9 Supply of transport by the same supplier .............................................................. 10 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ..................................................................... 11 FEEDBACK AND COMMENTS ............................................................................... 14 FURTHER INFORMATION ...................................................................................... 14 i Copyright Reserved © 2015 Royal Malaysian Customs Department GUIDE ON PASSENGER TRANSPORTATION As at 26 APRIL 2015 INTRODUCTION 1. This Industry Guide is prepared to assist you in understanding matters with regards to Goods and Services Tax (GST) treatment on passenger