Appendix: Selection of Original Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quint : an Interdisciplinary Quarterly from the North 1

the quint : an interdisciplinary quarterly from the north 1 Editorial Advisory Board the quint volume ten issue two Moshen Ashtiany, Columbia University Ying Kong, University College of the North Brenda Austin-Smith, University of Martin Kuester, University of Marburg an interdisciplinary quarterly from Manitoba Ronald Marken, Professor Emeritus, Keith Batterbe. University of Turku University of Saskatchewan the north Donald Beecher, Carleton University Camille McCutcheon, University of South Melanie Belmore, University College of the Carolina Upstate ISSN 1920-1028 North Lorraine Meyer, Brandon University editor Gerald Bowler, Independent Scholar Ray Merlock, University of South Carolina Sue Matheson Robert Budde, University Northern British Upstate Columbia Antonia Mills, Professor Emeritus, John Butler, Independent Scholar University of Northern British Columbia David Carpenter, Professor Emeritus, Ikuko Mizunoe, Professor Emeritus, the quint welcomes submissions. See our guidelines University of Saskatchewan Kyoritsu Women’s University or contact us at: Terrence Craig, Mount Allison University Avis Mysyk, Cape Breton University the quint Lynn Echevarria, Yukon College Hisam Nakamura, Tenri University University College of the North Andrew Patrick Nelson, University of P.O. Box 3000 Erwin Erdhardt, III, University of Montana The Pas, Manitoba Cincinnati Canada R9A 1K7 Peter Falconer, University of Bristol Julie Pelletier, University of Winnipeg Vincent Pitturo, Denver University We cannot be held responsible for unsolicited Peter Geller, -

Ricci (Matteo)

Ricci (Matteo) 利瑪竇 (1552-1610) Matteo Ricci‟s portrait painted on the 12th May, 1610 (the day after Ricci‟s death 11-May-1610) by the Chinese brother Emmanuel Pereira (born Yu Wen-hui), who had learned his art from the Italian Jesuit, Giovanni Nicolao. It is the first oil painting ever made in China by a Chinese painter.The age, 60 (last word of the Latin inscription), is incorrect: Ricci died during his fifty-eighth year. The portrait was taken to Rome in 1614 and displayed at the Jesuit house together with paintings of Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier. It still hangs there. Matteo Ricci was born on the 6th Oct 1552, in central Italy, in the city of Macerata, which at that time was territory of the Papal State. He first attended for seven years a School run by the Jesuit priests in Macerata, later he went to Rome to study Law at the Sapienza University, but was attracted to the religious life. In 1571 ( in opposition to his father's wishes), he joined the Society of Jesus and studied at the Jesuit college in Rome (Collegio Romano). There he met a famous German Jesuit professor of mathematics, Christopher Clavius, who had a great influence on the young and bright Matteo. Quite often, Ricci in his letters from China will remember his dear professor Clavius, who taught him the basic scientific elements of mathematics, astrology, geography etc. extremely important for his contacts with Chinese scholars. Christopher Clavius was not a wellknown scientist in Europe at that time, but at the “Collegio Romano”, he influenced many young Jesuits. -

Strategies of Defending Astrology: a Continuing Tradition

Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition by Teri Gee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Teri Gee (2012) Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition Teri Gee Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Astrology is a science which has had an uncertain status throughout its history, from its beginnings in Greco-Roman Antiquity to the medieval Islamic world and Christian Europe which led to frequent debates about its validity and what kind of a place it should have, if any, in various cultures. Written in the second century A.D., Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos is not the earliest surviving text on astrology. However, the complex defense given in the Tetrabiblos will be treated as an important starting point because it changed the way astrology would be justified in Christian and Muslim works and the influence Ptolemy’s presentation had on later works represents a continuation of the method introduced in the Tetrabiblos. Abû Ma‘shar’s Kitâb al- Madkhal al-kabîr ilâ ‘ilm ahk. âm al-nujûm, written in the ninth century, was the most thorough surviving defense from the Islamic world. Roger Bacon’s Opus maius, although not focused solely on advocating astrology, nevertheless, does contain a significant defense which has definite links to the works of both Abû Ma‘shar and Ptolemy. As such, he demonstrates another stage in the development of astrology. -

Break out Sessions Speakers for October 3, 2019

BREAK OUT SESSIONS SPEAKERS FOR OCTOBER 3, 2019 (This schedule may be subject to changes. Please see the final schedule at the conference itself.) Oct. 3, 2019, Aula 10 (coordinated by Joseph d’Amecourt, OP) 2:30 pm Emmanuel Durand, OP “Who delineates the Impossible?” In this talk, I will attempt to bring omnipotence and almightiness together. Searching for integration and unity relies on the assumption that reason and faith aim at the very same truth who is God's Wisdom, embodied in the created order and in the Paschal mystery. Instead of fostering a sharp divide between almightiness and omnipotence, I will argue that the very same attribute of the One God might be approached by both philosophers and theologians, relying on their different kinds of judgement. The key to this epistemological argument will be provided by Thomas Aquinas analysis of the possible and the impossible. 3:00 pm Gaston LeNotre “On the Merely Metaphysical Impossibility of the Annihilation of Creatures” Since the predicate in the statement, “the creature does not exist at all” does not contradict its subject, Thomas argues that God must be able to reduce the creature to nothing (De Potentia q. 5, a. 3). Thomas nevertheless also affirms that the created universe will never be annihilated. In the same texts where he talks about God’s ability to annihilate creatures, Thomas also outlines the reality that God does not and would not annihilate creatures. The distinction sometimes relies upon considering God’s power absolutely and considering God’s power in relation to His wisdom or foreknowledge (Quodlibet IV, q. -

Christian Scholar Xu Guangqi and the Spread of Catholicism in Shanghai

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 7, No. 1; 2015 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Christian Scholar Xu Guangqi and the Spread of Catholicism in Shanghai Shi Xijuan1 1 Doctoral Programme, Graduate School of Humanities, Kyushu University, Japan Correspondence: Shi Xijuan, Doctoral Programme, Graduate School of Humanities, Kyushu University, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 28, 2014 Accepted: November 6, 2014 Online Published: November 13, 2014 doi:10.5539/ach.v7n1p199 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v7n1p199 Abstract Xu Guangqi, one of the first and most notable Christian scholars in the Ming Dynasty, cast a profound influence on the spread of Catholicism in Shanghai. After his conversion, Xu Guangqi successfully proselytized all of his family members by kinship and affinity, a fact that was foundational to the development of Jesuit missionary work in Shanghai. His social relationships with pupils, friends, and officials also significantly facilitated the proliferation of Catholicism in Shanghai. This paper expands the current body of literature on Chinese–Christian scholar Xu Guangqi and his role in the spread of Catholicism in Shanghai during the late Ming and early Qing. Though there are several extant studies on this topic, most of them focus on Xu’s personal achievements and neglect the areas that this paper picks up: the role of Xu’s family and social status in his proliferate evangelism, and the longevity his influence had even beyond his own time. Through this approach, this paper aims to attain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of Xu Guangqi’s influence on the dissemination and perdurance of Catholicism in Shanghai. -

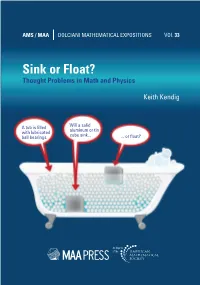

Sink Or Float? Thought Problems in Math and Physics

AMS / MAA DOLCIANI MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITIONS VOL AMS / MAA DOLCIANI MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITIONS VOL 33 33 Sink or Float? Sink or Float: Thought Problems in Math and Physics is a collection of prob- lems drawn from mathematics and the real world. Its multiple-choice format Sink or Float? forces the reader to become actively involved in deciding upon the answer. Thought Problems in Math and Physics The book’s aim is to show just how much can be learned by using everyday Thought Problems in Math and Physics common sense. The problems are all concrete and understandable by nearly anyone, meaning that not only will students become caught up in some of Keith Kendig the questions, but professional mathematicians, too, will easily get hooked. The more than 250 questions cover a wide swath of classical math and physics. Each problem s solution, with explanation, appears in the answer section at the end of the book. A notable feature is the generous sprinkling of boxes appearing throughout the text. These contain historical asides or A tub is filled Will a solid little-known facts. The problems themselves can easily turn into serious with lubricated aluminum or tin debate-starters, and the book will find a natural home in the classroom. ball bearings. cube sink... ... or float? Keith Kendig AMSMAA / PRESS 4-Color Process 395 page • 3/4” • 50lb stock • finish size: 7” x 10” i i \AAARoot" – 2009/1/21 – 13:22 – page i – #1 i i Sink or Float? Thought Problems in Math and Physics i i i i i i \AAARoot" – 2011/5/26 – 11:22 – page ii – #2 i i c 2008 by The -

IJR-1, Mathematics for All ... Syed Samsul Alam

January 31, 2015 [IISRR-International Journal of Research ] MATHEMATICS FOR ALL AND FOREVER Prof. Syed Samsul Alam Former Vice-Chancellor Alaih University, Kolkata, India; Former Professor & Head, Department of Mathematics, IIT Kharagpur; Ch. Md Koya chair Professor, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam, Kerala , Dr. S. N. Alam Assistant Professor, Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, National Institute of Technology Rourkela, Rourkela, India This article briefly summarizes the journey of mathematics. The subject is expanding at a fast rate Abstract and it sometimes makes it essential to look back into the history of this marvelous subject. The pillars of this subject and their contributions have been briefly studied here. Since early civilization, mathematics has helped mankind solve very complicated problems. Mathematics has been a common language which has united mankind. Mathematics has been the heart of our education system right from the school level. Creating interest in this subject and making it friendlier to students’ right from early ages is essential. Understanding the subject as well as its history are both equally important. This article briefly discusses the ancient, the medieval, and the present age of mathematics and some notable mathematicians who belonged to these periods. Mathematics is the abstract study of different areas that include, but not limited to, numbers, 1.Introduction quantity, space, structure, and change. In other words, it is the science of structure, order, and relation that has evolved from elemental practices of counting, measuring, and describing the shapes of objects. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. They resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity. -

THE INVENTION of ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY 1. Introductory

THE INVENTION OF ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY Christoph Lüthy Center for Medieval and Renaissance Natural Philosophy University of Nijmegen1 1. Introductory Puzzlement For centuries now, particles of matter have invariably been depicted as globules. These glob- ules, representing very different entities of distant orders of magnitudes, have in turn be used as pictorial building blocks for a host of more complex structures such as atomic nuclei, mole- cules, crystals, gases, material surfaces, electrical currents or the double helixes of DNA. May- be it is because of the unsurpassable simplicity of the spherical form that the ubiquity of this type of representation appears to us so deceitfully self-explanatory. But in truth, the spherical shape of these various units of matter deserves nothing if not raised eyebrows. Fig. 1a: Giordano Bruno: De triplici minimo et mensura, Frankfurt, 1591. 1 Research for this contribution was made possible by a fellowship at the Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschafts- geschichte (Berlin) and by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), grant 200-22-295. This article is based on a 1997 lecture. Christoph Lüthy Fig. 1b: Robert Hooke, Micrographia, London, 1665. Fig. 1c: Christian Huygens: Traité de la lumière, Leyden, 1690. Fig. 1d: William Wollaston: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1813. Fig. 1: How many theories can be illustrated by a single image? How is it to be explained that the same type of illustrations should have survived unperturbed the most profound conceptual changes in matter theory? One needn’t agree with the Kuhnian notion that revolutionary breaks dissect the conceptual evolution of science into incommensu- rable segments to feel that there is something puzzling about pictures that are capable of illus- 2 THE INVENTION OF ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY trating diverging “world views” over a four-hundred year period.2 For the matter theories illustrated by the nearly identical images of fig. -

Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony

he collection of essays presented in “Devotional Cross-Roads: Practicing Love of God in Medieval Gaul, Jerusalem, and Saxony” investigates test case witnesses of TChristian devotion and patronage from Late Antiquity to the Late Middle Ages, set in and between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, as well as Gaul and the regions north of the Alps. Devotional practice and love of God refer to people – mostly from the lay and religious elite –, ideas, copies of texts, images, and material objects, such as relics and reliquaries. The wide geographic borders and time span are used here to illustrate a broad picture composed around questions of worship, identity, reli- gious affiliation and gender. Among the diversity of cases, the studies presented in this volume exemplify recurring themes, which occupied the Christian believer, such as the veneration of the Cross, translation of architecture, pilgrimage and patronage, emergence of iconography and devotional patterns. These essays are representing the research results of the project “Practicing Love of God: Comparing Women’s and Men’s Practice in Medieval Saxony” guided by the art historian Galit Noga-Banai, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the histori- an Hedwig Röckelein, Georg-August-University Göttingen. This project was running from 2013 to 2018 within the Niedersachsen-Israeli Program and financed by the State of Lower Saxony. Devotional Cross-Roads Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony Edited by Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover Röckelein/Noga-Banai/Pinchover Devotional Cross-Roads ISBN 978-3-86395-372-0 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover (Eds.) Devotional Cross-Roads This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

On the Chiral Archimedean Solids Dedicated to Prof

Beitr¨agezur Algebra und Geometrie Contributions to Algebra and Geometry Volume 43 (2002), No. 1, 121-133. On the Chiral Archimedean Solids Dedicated to Prof. Dr. O. Kr¨otenheerdt Bernulf Weissbach Horst Martini Institut f¨urAlgebra und Geometrie, Otto-von-Guericke-Universit¨atMagdeburg Universit¨atsplatz2, D-39106 Magdeburg Fakult¨atf¨urMathematik, Technische Universit¨atChemnitz D-09107 Chemnitz Abstract. We discuss a unified way to derive the convex semiregular polyhedra from the Platonic solids. Based on this we prove that, among the Archimedean solids, Cubus simus (i.e., the snub cube) and Dodecaedron simum (the snub do- decahedron) can be characterized by the following property: it is impossible to construct an edge from the given diameter of the circumsphere by ruler and com- pass. Keywords: Archimedean solids, enantiomorphism, Platonic solids, regular poly- hedra, ruler-and-compass constructions, semiregular polyhedra, snub cube, snub dodecahedron 1. Introduction Following Pappus of Alexandria, Archimedes was the first person who described those 13 semiregular convex polyhedra which are named after him: the Archimedean solids. Two representatives from this family have various remarkable properties, and therefore the Swiss pedagogicians A. Wyss and P. Adam called them “Sonderlinge” (eccentrics), cf. [25] and [1]. Other usual names are Cubus simus and Dodecaedron simum, due to J. Kepler [17], or snub cube and snub dodecahedron, respectively. Immediately one can see the following property (characterizing these two polyhedra among all Archimedean solids): their symmetry group contains only proper motions. There- fore these two polyhedra are the only Archimedean solids having no plane of symmetry and having no center of symmetry. So each of them occurs in two chiral (or enantiomorphic) forms, both having different orientation. -

Bolyai, János

JÁNOS BOLYAI (December 15, 1802 – January 27, 1860) by Heinz Klaus Strick, Germany The portrait of the young man depicted on the Hungarian postage stamp of 1960 is that of JÁNOS BOLYAI, one of Hungary’s most famous mathematicians. The portrait, however, was painted only after his death, so it is anyone’s guess whether it is a good likeness. JÁNOS grew up in Transylvania (at the time, part of the Habsburg Empire, today part of Romania) as the son of the respected mathematician FARKAS BOLYAI. JÁNOS’s father, born in 1775, has attended school only until the age of 12, and was then appointed tutor to the eight-year-old son, SIMON, a scion of the wealthy noble KEMÉNY family. Three years later, he and his young charge together continued their educations at the Calvinist College in Kolozsvár. In 1796, he accompanied SIMON first to Jena, and then to Göttingen, where they attended university together. FARKAS had many interests, but now he finally had enough time to devote himself systematically to the study of mathematics. Through lectures given by ABRAHAM GOTTHELF KÄSTNER, he came to know his contemporary CARL FRIEDRICH GAUSS, and the two became friends. In autumn 1798, SIMON KEMÉNY returned home, leaving his “tutor” penniless in Göttingen; it was only a year later that FARKAS was able to return home, on foot. There he married and took an (ill-paying) position as a lecturer in mathematics, physics, and chemistry at the Calvinist College in Marosvásárhely (today Târgu Mures, Romania). To supplement his income, he wrote plays and built furnaces. -

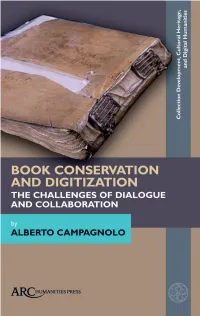

Book Conservation and Digitization the Challenges of Dialogue And

i BOOK CONSERVATION AND DIGITIZATION ii COLLECTION DEVELOPMENT, CULTURAL HERITAGE, AND DIGITAL HUMANITIES This exciting series publishes both monographs and edited thematic collections in the broad areas of cultural heritage, digital humanities, collecting and collections, public history and allied areas of applied humanities. The aim is to illustrate the impact of humanities research and in particular relect the exciting new networks developing between researchers and the cultural sector, including archives, libraries and museums, media and the arts, cultural memory and heritage institutions, festivals and tourism, and public history. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE ONLY iii BOOK CONSERVATION AND DIGITIZATION THE CHALLENGES OF DIALOGUE AND COLLABORATION by ALBERTO CAMPAGNOLO AND CONTRIBUTORS iv British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. © 2020, Arc Humanities Press, Leeds The author asserts their moral right to be identiied as the author of this work. Permission to use brief excerpts from this work in scholarly and educational works is hereby granted pro- vided that the source is acknowledged. Any use of material in this work that is an exception or limitation covered by Article 5 of the European Union’s Copyright Directive (2001/ 29/ EC) or would be determined to be “fair use” under Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act September 2010 Page 2 or that satisies the conditions speciied in Section 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act (17 USC §108, as revised by P.L.94– 553) does not require the Publisher’s permission. FOR PRIVATE AND ISBN (print): 9781641890533NON-COMMERCIAL eISBN (PDF): 9781641890540 USE ONLY www.arc- humanities.org Printed and bound in the UK (by Lightning Source), USA (by Bookmasters), and elsewhere using print-on-demand technology.