White Paper Type+Tech® Black[Foundry]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Graphie Latine Movement and the French Typography Manuel Sesma Prieto

UNIVERSITÉ PARIS 1 PANTHÉON-SORBONNE CENTRE DE RECHERCHE HiCSA (Histoire culturelle et sociale de l’art - EA 4100) UNE ÉMERGENCE DU DESIGN FRANCE, 20e SIÈCLE Sous la direction de Stéphane Laurent Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne THE GRAPHIE LATINE MOVEMENT AND THE FRENCH TYPOGRAPHY MANUEL SESMA PRIETO Pour citer cet article Manuel Sesma Prieto, « The Graphie Latine Movement and the French Typogra- phy », dans Stéphane Laurent (dir.), Une émergence du design. France 20e siècle, Paris, site de l’HiCSA, mis en ligne en octobre 2019, p. 126-143. THE GRAPHIE LATINE MOVEMENT AND THE FRENCH TYPOGRAPHY MANUEL SESMA PRIETO Associate professor, Facultad de Bellas Artes, Universidad Complutense de Madrid Introduction Most works dealing with the history of typography, many of Anglo-Saxon authors, reflect the period covered by the two decades after World War II practically dominated by neogrotesque typefaces. However, there were some reactions against this predominance, mainly from traditionalist positions that are rarely studied. The main objective of this research is thus to reveal the particular case of France, where there was widespread opposition to linear typefaces, which results into different manifestations in the field of national typography. This research wants therefore to situate the French typographical thought (which partially reflected the traditionalism of British typographical reformism led by Stanley Morison 1) within the history of European typography, and in a context dominated by the modern proposals arising mainly from Switzerland. This French thought is mostly shown in a considerable number of articles published in various specialist and professional press media, which perfectly reflected the general French atmosphere. -

Hebrew Type Design in the Context of the Book Art Movement and New

Philipp Messner Hebrew Type Design in the Context of the Book Art Movement and New Typography "New Book Art" ("Neue Buchkunst") was the motto under which efforts were made, in the spirit of the English Arts and Crafts Movement, toward the revival of book and type design in turn-of-the-twentieth century Germany. This revival movement perceived itself as a reaction to the country's accelerated industrialization, especially since the founding of the Reich in 1871. The replacement of traditional craft by increasingly industrial production lines effected a variety of everyday consumer products, including the manufacturing of books. According to contemporary commentators this led to deterioration in the material and aesthetic quality of books. Similarly to other industrially manufactured products around the turn of the century, an expectation emerged for books to have a contemporary, functional, and materially sound form. This demand encompassed all aspects of the book, including printing types. Consequently, visual artists were now engaged to design typefaces. Early examples were still heavily influenced by Art Nouveau, but after World War I there was a turn to historical forms with a bias toward handwritten scripts. This was influenced largely by the English calligrapher and type designer Edward Johnston, who taught at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London. His calligraphic method, which he based on old handwriting forms, became famous in Germany, in part thanks to the work of his pupil and translator, Anna Simons. Type design issues thus received a notably traditional treatment, defined above all by intensive engagement with historical forms. This tendency largely defined the personal styles of Franzisca Baruch and Henri Friedlaender. -

Logo Usage Color System Typography

LOGO & TYPOGRAPHY GUIDELINES Logo Usage Color System While each project may be unique, the logo should The City of Fargo logo consists of two primary colors, remain consistent. Keep it simple. Clean. And resist blue and black. The full-color version is the preferred the impulse to change it up. Even small changes can usage for all printed material or promotional items. devalue the strength of the City’s logo. However, do not print the full-color version over unacceptable background colors. For four-color offset printing, use the four-color Pantone equivalents. RGB COLOR BLACK values are provided for on-screen usage ONLY. The secondary color can be used when creating layouts. It is a brand extension to the primary blue and black. REVERSED B&W PRIMARY SECONDARY BLUE BLACK BLUE 2 PANTONE PANTONE PANTONE 3005 UP Process Black 295 UP CMYK CMYK CMYK 99 22 0 1 0 0 0 100 99 51 8 36 RGB RGB RGB MINIMUM CLEAR SPACE 0 125 213 35 31 32 0 78 125 Surround the logo with space. The minimum amount of space surrounding the logo must be equal to the height (x) of the “o.” The diagram below illustrates the area of minimum clear space required. Typography The font Gotham is used for all printed materials. Gotham is a clean, modern sans serif. Using one typeface ensures all visual communications are consistent. By incorporating different weights and treatments, a wide range of effects can be achieved while maintaining consistency across all communication and materials. Gotham Light Gotham Bold Gotham Light Italic Gotham Bold Italic Gotham Book Gotham Black Gotham Book Italic Gotham Black Italic Logo Taglines Gotham Medium Gotham Medium Italic The “Far More” tagline communicates the promise and position of the City and brand. -

To Download The

BRAND GUIDELINES CITY OF NEW BEDFORD BRAND GUIDELINES INTRO INTRODUCTION 4 You never get a 01 About the City of New Bedford’s brand 5 second chance to make CITY OF NEW BEDFORD 6 CNB Logo and usage 7 a first impression. 02 Color & variations 7 Clearspace & minimum sizes 8 Incorrect uses 9 CNB THE TYPOGRAPHY 10 Palatino Linotype 11 03 Open Sans 12 Placement of text over photos 13 CNB THE COLOR SYSTEM 14 04 Logo color palette 15 DESTINATION NEW BEDFORD 16 DNB The Logo & usage 17 05 Color & variations 17 Clearspace & minimum sizes 18 Incorrect uses 19 DNB THE COLOR SYSTEM 20 06 Logo color palette 21 SUITE FAMILY OF LOGOS 22 City of New Bedford, 23 07 Destination New Bedford and City initiative logo suite Contact Information 24 2 3 CITY OF NEW BEDFORD BRAND GUIDELINES About the brand A vibrant city brimming with culture, history, art, tourism and technology, the City of New Bedford is located on the southeastern coastline of Massachusetts. Since the 17th Century, New Bedford has been known as a city of firsts. We are proud to have been the “City that lit the world,” a major station of the Underground Railroad, and one of the largest producers of cotton yarns and textiles in the country. Today we are the #1 Fishing Port in America. A city born of and empowered by immigrants, we are proud that our diversity continues to help us “light the way” into the 21st Century. The vision for our brand springs from the roots of who we are and is intended to 01INTRODUCTION capture a colorful palette of people, history, and technology, to take pride in our diverse ABOUT THE CITY OF strengths, and to remind us that from our very inception, together we have been lighting NEW BEDFORD’S BRAND the way. -

Graphic Standards – Durham

Graphic Standards Manual & Style Guide THE CITY OF DURHAM Produced by the Office of Public Affairs | Rev: March 2006 The City of Durham Graphic Standards Manual & Style Guide X Table of Contents 3 SEC TION I The Identity Design System 9 SEC TION II Operational Materials 23 SECTION III Advertising 25 SEC TION IV Signage and Promotional Materials 30 SEC TION V Glossary, Grammar and Reproduction Materials Section I : The Identity Design System 3 Introduction: The City of Durham Organizational Identity Program THE CITY OF DURHAM The City of Durham consists of many departments whose goals are to improve the quality of life in our community by delivering cost-effective, highly responsive services with integrity and friendliness. While delivery of these services is primary, equally important is how the City communicates the types of services that it provides to both its internal and external customers. To achieve this goal, the City has adopted an updated organizational identity program that results in a unified and cohesive image. This identity must be used when creating materials for the City of Durham. The City of Durham Organizational Identity In 1991, the City of Durham adopted a logo to represent City government. This logo is used citywide to reflect the organizational identity of the City. Graphic standards have been established for usage of the logo to serve as a guide to departments and offices and are outlined in this manual. ABOUT THE CITY’S LOGO The City of Durham flag unites our rich history with what promises to be a dynamic and prosperous future. -

The Typography of Law Reviews: a Typographic Survey of Legal Periodicals

The Typography of Law Reviews: A Typographic Survey of Legal Periodicals Ambrogino Giusti Submitted to Professor Penny A. Hazelton to fulfill course requirements for Current Issues in Law Librarianship, LIS 595, and to fulfill the graduation requirement of the Culminating Experience Project for MLIS University of Washington Information School Seattle, Washington May 30, 2016 Typefaces are the clothes words wear, and just as we make judgments about people by the clothes they wear, so we make judgments about the information we’re reading by the typefaces. - Caroline Archer1 Times New Roman is a workhorse font that’s been successful for a reason. Yet it’s an open question whether its longevity is attributable to its quality or merely its ubiquity. - Matthew Butterick2 Keywords fonts, law reviews, law journals, legal periodicals, legal publications, typefaces, typography 1 Sam McManis, What Your Font Choice Says About You, THE ROANOKE TIMES (Jan. 13, 2008), http://www.roa- noke.com/webmin/features/what-your-font-choice-says-about-you/article_44076b07-db52-585b-af72- 84dc4bc4c8e6.html. 2 Matthew Butterick, A Brief History of Times New Roman, in BUTTERICK’S PRACTICAL TYPOGRAPHY (2016), http://practi- caltypography.com/times-new-roman.html. Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 History of Typography ............................................................................................................................ -

Brand Guidelines

BRAND GUIDELINES 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS BRAND BASICS 3 BRAND POSITIONING 4 BRAND MARKS 6 Spirit Mark 6 SU Interlock 9 Wordmark 12 Seal & Signature 15 COLOR 21 TYPOGRAPHY 26 Neutraface 2 27 Neutraface 2 Slab 28 Knockout 29 Frame 32 Web & Free Alternatives 33 Typography Application 34 PHOTOGRAPHY 39 Campus & Seattle 39 People: Undergraduate 40 People: Graduate Staff & Alumni 41 Classroom & Study 42 BRAND ELEMENTS 43 Color Overlays 43 Textures 46 Arrow-Tree Symbol 48 Secondary Icons 50 COMPOSITION 51 Undergraduate Materials 51 Graduate, Alumni & Professional Materials 53 COPY & HEADLINE TONE 55 2 BRAND BASICS SEATTLE UNIVERSITY WHAT IS THIS? This is a guideline on how to implement the Seattle University brand. Here the fundamentals of the brand are covered. As the brand evolves and becomes more defined, this guide will be updated. WHAT IS A BRAND? Seattle University is a cradle of social innovation. A transformative hub indiscernibly woven into the nation’s most progressive city. This is where all walks converge to find a better way forward. We are the boots on the ground and the engines of positive change. Building a successful brand takes the same focus, pride and will. The new look, feel, and tone con- tained in these brand standards reflect who and what make up the Seattle University story. The SU brand is the result of many different factors coming from many facets of this institution that ultimately come together to form an impression of who we are in people’s minds. Our brand is much more than the red and black. Our brand is what students, parents, academics, alumni, public servants, corporations, countries and outside observers all think, feel and respond to when they hear the name, “Seattle University.” The greatest successes at SU have been the result of people coming together and standing united to effect great change—just think about the Youth Initiative. -

Women Typeface Designers Laura Webber

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 5-1-1997 Women typeface designers Laura Webber Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Webber, Laura, "Women typeface designers" (1997). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Women Typeface Designers by Laura G.C. Webber A thesis project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree ofMaster of Science in the School of Printing Management and Sciences in the College ofImaging Arts and Sciences of the Rochester Institute ofTechnology May, 1997 Thesis Advisor: Professor Archibald D. Provan School ofPrinting Management and Sciences Rochester Institute ofTechnology Rochester, New York Certificate ofApproval Master's Thesis This is to certify that the Master's Thesis of Laura G.C. Webber With a major in Graphic Arts Publishing has been approved by the Thesis Committee as satisfactory for the thesis requirement for the Master ofScience degree at the convocation of May, 1997 Thesis Committee: Archibald Provan Thesis Advisor Marie Freckleton Graduate Program Coordinator Director or Designate Women Typeface Designers I, Laura G.C. Webber, hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library ofR.I.T to produce my thesis in whole or part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit. May 21, 1997 To my family and Steve, who selflessly give their support and encouragement. -

Visual Identity Standards

1 foundational elements City of Edmonton visual identity standards Designer’s Edition 3.3 Effective April, 2016 © The City of Edmonton moving forward As of June 2015, the new logo library replaced all previous logos. Please ensure previous versions are deleted from your system. Please note that the colours shown in this document are not visually accurate for colour matching. Always match colours to the latest edition of the PANTONE® Colour Formula Guide. For additional information and inquiries, please contact 311 or visit edmonton.ca/visualidentity to learn about the latest updates on City’s visual identity standards. * PANTONE® and other Pantone trademarks are the property of Pantone LLC. Visual identity Standards page 3 Foundational Elements Designer’s Edition 1.0 © The City of Edmonton 2016 contents 1 | introduction 5 | typography 04 Using these Standards 28 Primary Typefaces 05 Introduction to the Brand 32 System Typefaces 06 Logo: Past and Future 33 Google Typefaces 2 | logo 34 Setting Type Basics 07 Primary 6 | city symbols 08 Colour Options 36 City Crest 09 Alternate Colours 37 Versions 10 Monochrome 39 Clear Space 11 On-Screen 40 Single Colour Use 12 Wordmark 41 Crest with City Logo 13 Typeset Name Identification 7 | imagery 14 Clear Space: Primary 42 Photography 15 Clear Space: Wordmark 43 Selection 16 Minimum Size 44 Cropping 17 Misuse 8 | placement + grid 18 Placement with Partner Logos 45 Introduction to Identity System 3 | brand architecture 46 Grid 19 Department and Branch Identification 47 Primary Logo Staging 20 Internal -

(Mostly) True Story of Helvetica and the New York City Subway the (MOSTLY) TRUE STORY of HELVETICA and the NEW YORK CITY SUBWAY

2/10/2015 AIGA | The (Mostly) True Story of Helvetica and the New York City Subway THE (MOSTLY) TRUE STORY OF HELVETICA AND THE NEW YORK CITY SUBWAY Article by Paul Shaw November 18, 2008 Filed Under: Inspiration, history, Voice, information design, graphic design, typography, signage, design educators, students There is a commonly held belief that Helvetica is the signage typeface of the New York City subway system, a belief reinforced by Helvetica, Gary Hustwit's popular 2007 documentary about the typeface. But it is not true—or rather, it is only somewhat true. Helvetica is the official typeface of the MTA today, but it was not the typeface specified by Unimark International when it created a new signage system at the end of the 1960s. Why was Helvetica not chosen originally? What was chosen in its place? Why is Helvetica used now, and when did the changeover occur? To answer those questions this essay explores several important histories: of the New York City subway system, transportation signage in the 1960s, Unimark International and, of course, Helvetica. These four strands are woven together, over nine pages, to tell a story that ultimately transcends the simple issue of Helvetica and the subway. The Labyrinth As any New Yorker—or visitor to the city—knows, the subway system is a labyrinth. This is because it is an amalgamation of three separate systems, two of which incorporated earlier urban railway lines. The current New York subway system was formed in 1940 when the IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit), the BMT (BrooklynManhattan Transit) and the IND (Independent) lines were merged. -

Adobe® Font Name Reference Table (Fntnames.Pdf)

® Adobe® Font Name Reference Table (Fntnames.pdf) © 1997 Adobe Systems Incorporated. All rights reserved. ® Contents Typeface Trademark Symbols . 3 Introduction . 7 Font Name Reference Table . 11 Package 100 . 25 Package 200 . 42 Package 300 . 57 Package 400 . 74 Appendix A: Font Menu Name Revisions . 82 Appendix B: Trademark Attribution Statements . 91 Adobe Technical Support Technical Adobe ® Typeface Trademark Symbols The following list of trademark attribution symbols is arranged alpha- betically by family name. The name of the originating company (e.g., ITC) and prefixes such as “new” in names like “New Baskerville” were not used for alphabetizing. The trademark attribution statements are in Appendix B of this document. A Aachen™, Agfa®, Aja®, Berthold® Akzidenz Grotesk®, Albertus®, Aldus*, Alexa®, ITC American Typewriter®, Americana®, Amigo™, Andreas™, ITC Anna®, Antique Olive®, Apollo™, Arcadia*, Ariadne*, Arnold Bocklin*, Ashley Script™, New Aster™, Auriol*, ITC Avant Garde Gothic®, Avenir* B Baker Signet™, Balzano™, Banco®, Banshee™, Barmeno™, Berthold Baskerville™, Berthold Baskerville Book®, ITC New Baskerville®, ITC Bauhaus®, ITC Beesknees®, Bellevue™, Belwe™, Bembo®, ITC Benguiat®, ITC Benguiat Gothic®, ITC Berkeley Old Style®, Berliner Grotesk™, Berling™, Bermuda™, Bernhard Bold Condensed*, New Berolina™, Berthold®, Bickham Script™, Biffo™, Birch®, Blackoak®, Block Berthold®, Bauer Bodoni™, Berthold Bodoni®, Berthold Bodoni Old Face™, AG Book™, ITC Bookman®, Boton®, Boulevard™, Briem®, Bulmer™ C PMN Caecilia*, Caflisch Script®, -

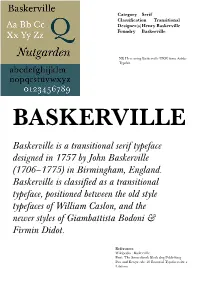

Sans Serif Typefaces By: Years, All of Which Were Designed by Ben- Ton and Issued by A.T.F

Category Serif Classification Transitional Designer(s) Henry Baskerville Foundry Baskerville NB Here using Baskerville URW from Adobe Typekit BASKERVILLE Baskerville is a transitional serif typeface designed in 1757 by John Baskerville (1706–1775) in Birmingham, England. Baskerville is classified as a transitional typeface, positioned between the old style typefaces of William Caslon, and the newer styles of Giambattista Bodoni & Firmin Didot. References Wikipedia : Baskerville Font: The Sourcebook Black dog Publishing Pau and Berger eds: 30 Essential Typefaces for a Lifetime History CHARACTERISTICS In Birmingham, England, Henry Baskerville ad- vanced the use of more delicate typefaces that could The Baskerville typeface is the result of withstand the repeated poundings on the press. He John Baskerville’s intent to improve upon also developed smoother paper so the typefaces could the types of William Caslon. He was aim- print without breaks or clogs. Had an airy quality ing at simplicity and quiet refinement due to the lightness of the letterforms and generosity though: of the page margins. Melted down his type after each printing. • increasing the contrast between thick and thin strokes Baskerville’s typeface was the culmination of a larg- • making the serifs sharper and more er series of experiments to improve legibility which tapered also included paper making and ink manufactur- • shifting the axis of rounded letters to a ing. His background as a writing master is evident more vertical position. in the distinctive swash tail on the uppercase Q and • making curved strokes more circular in in the cursive serifs in the Baskerville Italic. shape and making characters more regu- lar.