Antrocom Journal of Anthropology ANTROCOM Journal Homepage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Fresh Water Resources for Effective Crop Planning in South Andaman District

J Krishi Vigyan 2018, 7 (Special Issue) : 6-11 DOI : 10.5958/2349-4433.2018.00148.4 Assessment of Fresh Water Resources for Effective Crop Planning in South Andaman District B K Nanda1, N Sahoo2, B Panigrahi3 and J C Paul4 ICAR-KVK, Port Blair (Andaman and Nicobar Group of Islands) ABSTRACT The rainfall data for 40 yr from 1978 to 2017 of the rainfed tropical islands of South Andaman district of Andaman and Nicobar group of islands were analyzed to find out the weekly effective rainfall. Weekly and monthly effective runoff was calculated by following the US Soil Conservation Service - Curve Number (SCS-CN) method. The value of weekly effective rainfall and monthly effective runoff at different level of probabilities was obtained with the help of ‘FLOOD’ software. The sum of effective rainfalls of standard meteorological weeks from 18th to 48th gives the value of fresh water resource availability during kharif season and the same value at 80 percent level of probability was estimated to be 2.07 X105 ha.m. The sum of expected runoff of every month resulted due to the effective rainfall gives the water resource availability during rabi season and its value at 80 percent level of probability was found to be 4.8 X 103 ha.m. All these information will immensely help the farmers, policy makers, planners and researchers to prepare a comprehensive crop action plan for the South Andaman district to make the agriculture profitable and sustainable. Key Words: Curve number, Effective rainfall, Fresh water resources, Storage capacity, Tropical islands INTRODUCTION the Nicobar Islands, which is separated by 10o Small islands are prevalent in the humid channel. -

Srjis/Bimonthly/Dr. Sushim Kumar Biswas (5046-5055)

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/DR. SUSHIM KUMAR BISWAS (5046-5055) SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE OF MIGRANT MUSLIM WORKERS IN ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS Sushim Kumar Biswas, Ph. D. HOD, Department of Economics, Andaman College (ANCOL), Port Blair Abstract Socio-economic status (SES) is a multidimensional term. Today SES is deemed to be a hyper - dimensional latent variable that is difficult to elicit. Socioeconomic status is a latent variable in the sense that, like mood or well -being, it cannot be directly measured (Oakes & Rossi, 2003) and it is, some-what, associated with normative science. Finally, it converges to the notion that the definition of SES revolves around the issue of quantifying social inequality. However, it poses a serious problem for the researcher to measure the socio-economic status of migrant workers for short duration during the course of the year. Even in the absence of a coherent national policy on internal migration, millions of Indians are migrating from one destination to another with different durations (Chandrasekhar, 2017). The Andaman & Nicobar Islands(ANI) is no exception and a large number of in-migration is taking place throughout the year. Towards this direction, an attempt has been made to examine the socio-economic profile of migrant Muslim workers who have come to these Islands from West Bengal and Bihar in search of earning their livelihood. An intensive study has been conducted to assess their socio-economic well-being, literacy, income, health hazards, sanitation & medical facilities, family size, indebtedness, acculturation, social status, etc. This study reveals that their socio-economic profile in these Islands are downtrodden, nevertheless they are in a better state than their home town. -

1. the Principal Chief Conservatorof Forests (ANI) Van Sadan, Haddo. Port Blair

NO. LA. G-211579 OFFICE OF THE DIVISIONAL FOREST OFFICER Tte USHI/LITTLE ANDAMAN Hut Bay dated the 26 September, 2020. To The Chief Conservator of Forests (Territorial), Van Sadan, Haddo, Port Blair. 0.3693 Kms of deemed forest for Sub: Diversion of 70. 9037 Sq. kms of Forest area and Sq. sustainable development of Little Andaman Island -submission of revised Part-Il- reg: dated 11/09/2020. Ref: PCCF (CRZ&FC) letter No. PCCF FCA/326/Vol-I1/198 Sir, for diversion of Kindly find enclosed herewith the revised Part-lI along with Annexures 7127.3 Ha. of Forest land (70. 9037 Sq. kms of Forest area and 0.3693 Sq. Kms of deemed forest) in favour of for sustainable deveiopment of Little Andaman Island envisaged by the NITI Ayog ANIIDCO. Submitted for further course of action please. Yours faithfully, Encl: As above (To4T,HTEH) (P.K. Paul. iFS) Divisional Forest Officer ffei 3isHTH /Little Andaman Copy to: 1. The Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (ANI) Van Sadan, Haddo. Port Blair for favour of information. 2. The Chief Principal Conservator of Forests Van Sadan. Haddo. Port Blair (CZ&FC). for information and necessary action. 2 u PART-I State Serial Number of the proposal: 7. Location of the project/scheme . Union Territory Andaman & Nicobar Islands District South Andaman District 111 Forest Division Little Andaman Forest Division IV. Area of forest land proposed for 7127.3 Ha. of forest land. Out of the given Diversion (in ha.) proposed forest land, an area of 773.4 Ha. of notified forest has been reserved for PVTG (Particularly vulnerable tribal group - Onge) under ANIKPAT) regulation 1956. -

Civil Supplies Public Distribution Public Distribution Supplies & & Consumer System in the UT of a & N System in the UT Consumer Affairs, Port Islands

Section 4(1)b(i): Particulars of the organization, functions and duties. Clause Name of the Address Functions Duties Organization 1. Department Directorate of a. Implementation of Implementation of of Civil Civil Supplies Public Distribution Public Distribution Supplies & & Consumer System in the UT of A & N System in the UT Consumer Affairs, Port Islands. of A & N Islands. Affairs Blair. b. Monitoring and distribution of distribution of LPG and kerosene oil. c. Providing Family Identity Card (Ration Card) related services. e. Allotment of Fair Price Shops. f. Monitoring and publishing the prices of essential commodities and Market intervention Operations for controlling the open market prices if necessary. g. Protection of interest of Consumers under the Consumer Protection Act, 1986 through State Consumer Redressal Forum and District Forum. h. Implementation of Packaged commodities Rules, Enforcement of W & M Act, Stamping, Verification and calibration of W & M Instruments. Section 4(1)(b)(ii): Powers and Duties of Officers and Employees The details of the powers and duties of officers and employees of the authority by designation are as follows:- Sl.No Name of the Designation Duties Allotted Powers Officer/employees 1. Shri Devinder Singh Secretary-Cum- Overall supervision Secretary Secretary-Cum- Director(CS&CA) & HOD of the Department of Director (CS&CA) CS&CA 2. Shri Dhirendra Deputy Provide Assistance to Secretary Kumar Director(CS&CA) cum Director (CS&CA). Deputy Director Head of Office (CS&CA) Issuance of Ration Cards/Supervision of PDS Incharge of Enforcement Cell, Administration Branch/Vigilance Branch , Implementation of RTI Act, 2005 Public Information Officer of (CS&CA) 3 Shri V.R. -

District Statistical Handbook. 2010-11 Andaman & Nicobar.Pdf

lR;eso t;rs v.Meku rFkk fudksckj }hilewg ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS Published by : Directorate of Economics & Statistics ftyk lkaf[;dh; iqfLrdk Andaman & Nicobar Administration DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK Port Blair 2010-11 vkfFZkd ,oa lkaf[;dh funs'kky; v.Meku rFkk fudksckj iz'kklu iksVZ Cys;j DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ADMINISTRATION Printed by the Manager, Govt. Press, Port Blair PORT BLAIR çLrkouk PREFACE ftyk lkaf[;dh; iqfLrdk] 2010&2011 orZeku laLdj.k The present edition of District Statistical Hand Øe esa lksygok¡ gS A bl laLdj.k esa ftyk ds fofHkUu {ks=ksa ls Book, 2010-11 is the sixteenth in the series. It presents lacaf/kr egÙoiw.kZ lkaf[;dh; lwpukvksa dks ljy rjhds ls izLrqr important Statistical Information relating to the three Districts of Andaman & Nicobar Islands in a handy form. fd;k x;k gS A The Directorate acknowledges with gratitude the funs'kky; bl iqfLrdk ds fy, fofHkUu ljdkjh foHkkxksa@ co-operation extended by various Government dk;kZy;ksa rFkk vU; ,stsfUl;ksa }kjk miyC/k djk, x, Departments/Agencies in making available the statistical lkaf[;dh; vkWadM+ksa ds fy, muds izfr viuk vkHkkj izdV djrk data presented in this publication. gS A The publication is the result of hard work put in by Shri Martin Ekka, Shri M.P. Muthappa and Smti. D. ;g izdk'ku Jh ch- e¨gu] lkaf[;dh; vf/kdkjh ds Susaiammal, Senior Investigators, under the guidance of ekxZn'kZu rFkk fuxjkuh esa Jh ekfVZu ,Ddk] Jh ,e- ih- eqÉIik Shri B. Mohan, Statistical Officer. -

Policy Andaman and Nicobar

II. SOP REGARDING COVID-19 TESTING FOR TOURISTS COMING TO ANDAMAN ISLANDS On arrival at Port Blatr 1. The tourists need to carry COVID-19 negative test report from mainland based 1CMR approved lab using Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RTPCR). However, the sample for RTPCR test should have been taken within 48 hours prior to starting the journey from the origin station. (For e.g. if the tourist takes a flight from Delhi at 0600 hrs. on 1st September, 2021, the sample for RTPCR test should have beern taken not before 0600 hrs. on 30th August, 2021). 2. The tourists/visitors on arrival at Port Blair airport have to undergo mandatorily Covid-19 screening with RTPCR test free of cost. Thereafter the tourists/visitors are allowed to move to their respective hotels. However, they will have to be under quarantine at Port Blair in their hotels rooms until the result of RTPCR tests are received. In case of RTPCR positive test results, the tourists/visitors shall be remain in institutional quarantine in hotels notilied by the Hoteliers Association in consent with the A&N Administration, on rates as specified or to the designated hospital/ Covid-19 care centre on case to case basis. Other guidelines prescribed by the Ministry of Civil Aviation for airport (available at https://www.mohfw.gov.in and SOP) issued by Airport Manager, VSI also need to followed. 3. Tourists may also have to urndergo random Rapid Antigen Test conducted from time to time on payment basis as prescribed by A8N Administration. Incase tourist tests Positive for COVID-19 during stay 4. -

STATE ANNUAL ACTION PLAN of AYUSH UNDER NAM 2020-21 A

STATE ANNUAL ACTION PLAN Of AYUSH UNDER NAM 2020-21 A & N State AYUSH Society A & N ISLANDS a INDEX Point Chapter / Title Page Nos. Letter of Submission of AYUSH SAAP for the year 2O2O-2O21 (F. -- d No.4-99 / ANSAS/ NAM/ SAAP/ 2020-21/148 dt. 7th April, 2020 Recommendation of the UT Government of Andaman & Nicobar -- Islands in respect of the State Annual Action Plan (SAAP) from e Principal Secretary (Health), A & N Admn. -- Application Form- Annexure-I f-h Proforma -3 (Application form for grant-in-aid for strengthening of -- i-j ASU&H Drug Control Framework -- (Annexure (3-a) to Annexure (3-f) k-p CHAPTER – 1 1 Profile of AYUSH in the Union Territory 1.1 Geographical Scenario of A & N Islands 1.2 Primitive Tribal Groups Of A&N Islands 1.3 Administrative Divisions: 1 to 6 1.4 Demographic Profile: 1.5 Profile of Health Centers and Hospitals in the Health Department: 1.6 Profile of AYUSH under Health Department: CHAPTER – 2 2 Number of co-located AYUSH facilities before the launch of NHM: 2.1 Co-located & Isolated Institutions: 7 to 10 The manpower (posted at co-located dispensaries and AYUSH 2.2 Hospital before NHM: CHAPTER-3 Progress of implementation of mainstreaming of AYUSH during last 3 years: 3.1 Proposal submitted and approved components under NHM. No. of AYUSH facilities co-located (system wise) in DHs/CHCs/PHCs 3.2 after the launch of NHM and the doctors and para-medical staff posted on contractual basis. 11 to 16 3.3 Availability of AYUSH medicines in the Co-located facilities: Training provided to AYUSH Doctors last two years -

Government of India Ministry of Home Affairs Rajya Sabha Starred Question No. *105 to Be Answered on the 19Th December, 2018/ Ag

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. *105 TO BE ANSWERED ON THE 19TH DECEMBER, 2018/ AGRAHAYANA 28, 1940 (SAKA) FOREIGN NATIONAL IN RESTRICTED AREA IN ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS *105. SHRI RAJEEV CHANDRASEKHAR: Will the Minister of HOME AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) whether it is a fact that a foreign national had attempted to land in the out of bounds Sentinel Island in the Andamans for the purpose of illegal religious conversion of the native Sentinelese tribe which is an endangered community living in Andaman Island; (b) if so, what laws had been violated by the person and those that aided and abetted him and what is the status of prosecution of these people; and (c) what steps Government is taking to ensure enforcement of these areas prohibited to foreigners and to ensure strong action against those who violate rules? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (SHRI KIREN RIJIJU) (a) to (c): A statement is laid on the table of the house. --2-- STATEMENT IN REPLY TO PARTS (a) TO (c) OF RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. *105 FOR 19TH DECEMBER 2018 REGARDING ‘FOREIGN NATIONAL IN RESTRICTED AREA IN ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS’ (a) to (c): One U.S. national, Chau John Allen, visited the North Sentinel Island clandestinely with the help of five local fishermen in a mechanized dinghy. An F.I.R. has been lodged (No. 92/2018 dated 20.11.2018) u/s 282, 336, 304 and 120 B Indian Penal Code (I.P.C) read with Sections 7 and 8 of PAT Regulations, 1956 and Sections 14, 14A and 14C of The Foreigners Act, 1946 against seven persons who aided/ abetted the foreign national in reaching the North Sentinel Island. -

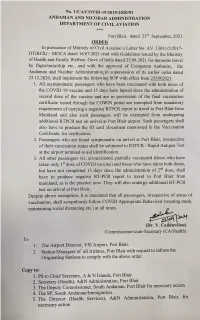

Andaman & Nicobar Administration Directorate of Civil Aviation

Pre-Feasibility Report For Development of Water Aerodrome at Swaraj Island, A&N Project Proponent “Andaman & Nicobar Administration Directorate of Civil Aviation” Pre-Feasibility Report for Development of Water Aerodrome at Swaraj Island, A&N TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION OF THE PROJECT/BACKGROUND INFORMATION .................... 2 2.1 Identification of Project and Project Proponent ............................................................... 2 2.1.1 Project Proponent ...................................................................................................... 2 2.1.2 Identification of Project ............................................................................................ 2 2.2 Brief Description of Nature of the Project ....................................................................... 2 2.3 Need for the Project and its Importance to the Country and or Region ........................... 3 2.4 Employment Generation (Direct and Indirect) due to the Project ................................... 3 3. PROJECT DISCRIPTION ...................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Type of Project ................................................................................................................. 4 3.2 Location of the Project Site .............................................................................................. 4 -

NVVN Pre-Feasibility Report for Proposed Gas Supply DATE: 13.08.2019 Infrastructure for Andaman & Nicobar Power Project REV

Doc. No.6400/ NVVN/RE/2019-04 NVVN Pre-feasibility Report for Proposed Gas Supply DATE: 13.08.2019 Infrastructure for Andaman & Nicobar Power Project REV. NO. : 0 Page 1of 18 PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT FOR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) STUDY FOR Proposed Gas Supply Infrastructure for Andaman & Nicobar Power Project IN HOPE TOWN AT FERRARGUNJ TEHSIL DIST. SOUTH ANDAMAN (ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS) NTPC VIDYUT VYAPAR NIGAM LIMITED (NVVN) (A wholly owned subsidiary of NTPC Ltd.) August, 2019 Doc. No.6400/ NVVN/RE/2019-04 NVVN Pre-feasibility Report for Proposed Gas Supply DATE: 13.08.2019 Infrastructure for Andaman & Nicobar Power Project REV. NO. : 0 Page 2of 18 TABLE OF CONTENTS Sl. No. Description Page No. 1.0 Executive Summary 1 2.0 Introduction of the Project & Background Information 1 3.0 Project Description 6 4.0 Site Analysis 9 5.0 Brief Planning 10 6.0 Proposed Infrastructure 11 7.0 Rehabilitation and Resettlement (R&R) Plan 12 8.0 Project Schedule & Cost Estimates 12 9.0 Analysis of Proposal ( Recommendations) 12 10.0 Environmental Aspects 12 EXHIBITS Exhibit Description Page No. No. I Index Map 14 II Vicinity Map 15 III General Layout Plan 16 IV General Features 17 ANNEXURES Annexure Description Page No. No. I Climatological Table at Port Blair 18 Doc. No.6400/ NVVN/RE/2019-04 NVVN Pre-feasibility Report for Proposed Gas Supply DATE: 13.08.2019 Infrastructure for Andaman & Nicobar Power Project REV. NO. : 0 Page 3of 18 1.0 Executive Summary Name of Project: Proposed Gas supply Infrastructure for Andaman & Nicobar Gas Power Project at Hope Town in Ferrargunj Tehsil of South Andaman District. -

11 CHAPTER 3 DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE Population As Per Census 2011 Population of a & N Islands Is 380581 It Was 356152 in 2001

CHAPTER 3 DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE Population As per Census 2011 population of A & N Islands is 380581 it was 356152 in 2001. The decadal growth recorded during 1991-2001 was 26.90% which has declined to 6.86 during 2001- 2011. There has been a continuous decline in the growth rate of population since 1971. Rural and Urban area wise population since1901 is given below: Statement 3.1: Rural & Urban Population Population 1901 1911 1921 1931 1941 1951 Rural 24649 26459 27086 29463 33768 23182 Urban --- --- --- --- --- 7789 Total 24649 26459 27086 29463 33768 30971 Population 1961 1971 1981 1991 2001 2011 Rural 49473 88915 139107 205706 239954 237093 Urban 14075 26218 49634 74955 116198 143488 Total 63548 115133 188741 280661 356152 380581 Chart 3.1 Population of A & N Islands from 1901 to 2011 400000 300000 200000 100000 0 1901 1911 1921 1931 1941 1951 1961 1971 1981 1991 2001 2011 Chart 3.2 250000 rural urban 200000 150000 100000 50000 0 1951 1961 1971 1981 1991 2001 2011 Urban population of A & N Islands is 37.7% that was 32.63 percent in 2001. 11 Annual Average Growth Rate of Population in A& N Islands: Statement 3.2: Growth Rate of Population Census Year Population Decadal growth rate Annual Exponential growth rate 1901 24649 --- 0.71 1911 26459 7.34 0.22 1921 27086 2.37 0.82 1931 29463 8.78 1.38 1941 33768 14.61 -0.86 1951 30971 (-) 8.28 7.20 1961 63548 105.19 5.98 1971 115133 81.17 4.92 1981 188741 63.93 3.97 1991 280661 48.70 2.37 2001 356152 26.90 2.40 2011 380581 6.86 0.67 Statement 3.3: District Wise Growth Rate of Population Population -

Application for the Grant of a Pass Under Section 7 of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation 1956

FORM ‘A’ (See Rule 4) Application for the grant of a Pass under Section 7 of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation 1956 Attested To Photograph paste here The Deputy Commissioner & One South Andaman District. attach I, …………………………………………(name of the applicant) hereby apply for a pass under Section 7 of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, 1956, and the rule made there under, authorizing me and my child/children aged below 15 years to enter and remain in the following reserved area in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands for the period commencing from Date…………………………… ending on date………………………… namely:- I. Detailed of reserved area:- …………………………………… II. Personal particulars 1. Name in full (in block Capitals) with aliases if any ………………………..... 2. Father’s/Husband’s Name …………………………………… 3. Date of birth, and present age: …………………… …………. 4. Place of birth, District and state in which situated: Vill………………Dist…… 5. Height in meters: ………………….. 6. Colour of hair: ………………….. 7. Colour of eyes: ………………….. 8. Distinguishing marks ………………….. 9. Present address in full: Vill……………………………Dist. ……………………… State………………………..Phone No……………….... 10. Permanent home address in full i.e. Village …………………………. Thana …………………………. District …………………………. State …………………………. 11. Actual date of arrival in A&N Islands……………………………………………… 12. Nationality ………………………………………………………………………………. 13. Religion …………………………………………………………………………………... 14. Vocation 2- 15. Whether held any office under the Govt. in the past and if so details thereof. 16. Particulars of places with period of residences Where the applicant was resided for more than One year at a time during the preceding 6 years: Residential address in full i.e. Name of the District village, Thana and District or Headquarters of the place Period house Number, Lane/Street/Road mentioned in the preceding and Town.