Reappraising the Eff Ects of Language Contact in the Torres Strait

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Many Voices Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Action Plan

Yetimarala Yidinji Yi rawarka lba Yima Yawa n Yir bina ach Wik-Keyangan Wik- Yiron Yam Wik Pa Me'nh W t ga pom inda rnn k Om rungu Wik Adinda Wik Elk Win ala r Wi ay Wa en Wik da ji Y har rrgam Epa Wir an at Wa angkumara Wapabura Wik i W al Ng arra W Iya ulg Y ik nam nh ar nu W a Wa haayorre Thaynakwit Wi uk ke arr thiggi T h Tjung k M ab ay luw eppa und un a h Wa g T N ji To g W ak a lan tta dornd rre ka ul Y kk ibe ta Pi orin s S n i W u a Tar Pit anh Mu Nga tra W u g W riya n Mpalitj lgu Moon dja it ik li in ka Pir ondja djan n N Cre N W al ak nd Mo Mpa un ol ga u g W ga iyan andandanji Margany M litja uk e T th th Ya u an M lgu M ayi-K nh ul ur a a ig yk ka nda ulan M N ru n th dj O ha Ma Kunjen Kutha M ul ya b i a gi it rra haypan nt Kuu ayi gu w u W y i M ba ku-T k Tha -Ku M ay l U a wa d an Ku ayo tu ul g m j a oo M angan rre na ur i O p ad y k u a-Dy K M id y i l N ita m Kuk uu a ji k la W u M a nh Kaantju K ku yi M an U yi k i M i a abi K Y -Th u g r n u in al Y abi a u a n a a a n g w gu Kal K k g n d a u in a Ku owair Jirandali aw u u ka d h N M ai a a Jar K u rt n P i W n r r ngg aw n i M i a i M ca i Ja aw gk M rr j M g h da a a u iy d ia n n Ya r yi n a a m u ga Ja K i L -Y u g a b N ra l Girramay G al a a n P N ri a u ga iaba ithab a m l j it e g Ja iri G al w i a t in M i ay Giy L a M li a r M u j G a a la a P o K d ar Go g m M h n ng e a y it d m n ka m np w a i- u t n u i u u u Y ra a r r r l Y L a o iw m I a a G a a p l u i G ull u r a d e a a tch b K d i g b M g w u b a M N n rr y B thim Ayabadhu i l il M M u i a a -

Your Labor Member in the Queensland Parliament

YOUR LABOR MEMBER IN THE QUEENSLAND PARLIAMENT Cape Vork / Douglas / Cooktown / Mareeba: Torres Strait / NPA P: 1800816264 - Fax: 07 40312437 P: 1800802391 - Fax: 07 4069 1620 PO Box 2080, Cairns 4870 PO Box 437, Thursday Island 4875 E: [email protected] E: cook.th [email protected] Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority Level 19 12 Creek Street BRISBANE QLD 4001 REVIEW OF SUN WATER PRICING STRUCTURE Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority by Jason O'Brien MP Member for Cook, on behalf of a constituent who is a Sun Water user, requesting changes to the pricing policy of Sun Water to their customers holding pension concession cards who access sun water for their domestic use only. Under the present Sun Water tariff structure they are able to negotiate how much revenue could be collected from variable and fixed charges. My submission is that Sun Water should be free to offer a Pensioner Water Subsidy Scheme for eligible pensions to reduce the impact of increased water price increases. This concession could be in the form of a rebate similar to the rate rebate scheme which applies across the state off local government rates charges. Sun Water must have the ability to provide water services to the community at a reasonable cost taking into account the most effective way to utilise the resource for the community's benefit. To this end pensions accessing Sun Water's resource purely for domestic use should be considered in a wider public interest context. Prices should be cost reflective and take into account relevant public interest matters such as pensioners accessing their resource In conclusion I submit that Sun Water should be providing a Pensioner Water Subsidy Scheme and the Queensland Competition Authority should recognise this as a public interest issue. -

LAADE W01 Sound Recordings Collected by Wolfgang Laade, 1963

Interim Finding aid LAADE_W01 Sound recordings collected by Wolfgang Laade, 1963-1965 Prepared February 2013 by MH Last updated 23 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening Some materials in this collection are restricted and may only be listened to by clients who have obtained permission from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. For more details, contact Access and Client Services by sending an email to [email protected] or phone (02) 6261 4212. Restrictions on use This collection is partially restricted. It contains some materials which may only be copied by clients who have obtained permission from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. For more details, contact Access and Client Services by sending an email to [email protected] or phone (02) 6261 4212. Permission must be sought from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1963-1965 Extent: 82 sound tape reels (ca. 34 hrs. 30 min.) : analogue, 3 3/4 ips, 2 track, mono. ; 7 in. (not held). Production history These recordings were collected by Dr Wolfgang Laade of the Freie Universität, West Berlin, between 1963 and 1965 at various locations on Cape York Peninsula and the Torres Strait Islands, Queensland, Australia. -

Sociality and Locality in a Torres Strait Community

Past Visions, Present Lives: sociality and locality in a Torres Strait community. Thesis submitted by Julie Lahn BA (Hons) (JCU) November 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology Faculty of Arts, Education and Social Sciences James Cook University Statement of Access I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper public written acknowledgment for any assistance that I have obtained from it. Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. _________________________________ __________ Signature Date ii Statement of Sources Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ____________________________________ ____________________ Signature Date iii Acknowledgments My main period of fieldwork was conducted over fifteen months at Warraber Island between July 1996 and September 1997. I am grateful to many Warraberans for their assistance and generosity both during my main fieldwork and subsequent visits to the island. -

Aboriginal and Indigenous Languages; a Language Other Than English for All; and Equitable and Widespread Language Services

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 819 FL 021 087 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph TITLE The National Policy on Languages, December 1987-March 1990. Report to the Minister for Employment, Education and Training. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. PUB DATE May 90 NOTE 152p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Advisory Committees; Agency Role; *Educational Policy; English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Role; *National Programs; Program Evaluation; Program Implementation; *Public Policy; *Second Languages IDENTIFIERS *Australia ABSTRACT The report proviCes a detailed overview of implementation of the first stage of Australia's National Policy on Languages (NPL), evaluates the effectiveness of NPL programs, presents a case for NPL extension to a second term, and identifies directions and priorities for NPL program activity until the end of 1994-95. It is argued that the NPL is an essential element in the Australian government's commitment to economic growth, social justice, quality of life, and a constructive international role. Four principles frame the policy: English for all residents; support for Aboriginal and indigenous languages; a language other than English for all; and equitable and widespread language services. The report presents background information on development of the NPL, describes component programs, outlines the role of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME) in this and other areas of effort, reviews and evaluates NPL programs, and discusses directions and priorities for the future, including recommendations for development in each of the four principle areas. Additional notes on funding and activities of component programs and AACLAME and responses by state and commonwealth agencies with an interest in language policy issues to the report's recommendations are appended. -

1 12Th Oecd-Japan Seminar: “Globalisation And

12TH OECD-JAPAN SEMINAR: “GLOBALISATION AND LINGUISTIC COMPETENCIES: RESPONDING TO DIVERSITY IN LANGUAGE ENVIRONMENTS” COUNTRY NOTE: AUSTRALIA LINGUISTIC CHALLENGES FOR MINORITIES AND MIGRANTS Australia is today a culturally diverse country with people from all over the world speaking hundreds of different languages. Australia has a broad policy of social inclusion, seeking to ensure that all Australians, regardless of their diverse backgrounds are fully included in and able to contribute to society. With its long history of receiving new visitors from overseas, and particularly with the explosion of immigration following World War II, Australia has a great deal of experience in dealing with the linguistic challenges of migrants and minorities. Instead of simply seeking to assimilate new arrivals, Australia seeks to integrate those people into society so that they are able to take full advantage of opportunities, but in a way that respects their cultural traditions and indeed values their diverse experiences. Snapshot of Australian immigration Australia's current Immigration Program allows people from any country to apply to visit or settle in Australia. Decisions are made on a non-discriminatory basis without regard to the applicant's ethnicity, culture, religion or language, provided that they meet the criteria set out in law. In 2005–06, there were 131 600 (ABS, 2006) people who settled permanently in Australia. The top ten countries of origin are: Country of birth % 1 United Kingdom 17.7 2 New Zealand 14.5 3 India 8.6 4 China (excluded SARs and Taiwan) 8.0 5 Philippines 3.7 6 South Africa 3.0 7 Sudan 2.9 8 Malaysia 2.3 9 Singapore 2.0 10 Viet Nam 2.0 Other 35.3 Total 100.0 1 According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2006 census data: Australia's immigrants come from 185 different countries Australians identify with some 250 ancestries and practise a range of religions. -

EALD Information (PDF, 434

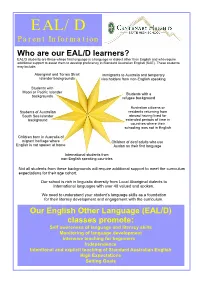

EAL/D Parent Information Who are our EAL/D learners? EAL/D students are those whose first language is a language or dialect other than English and who require additional support to assist them to develop proficiency in Standard Australian English (SAE). These students may include: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Immigrants to Australia and temporary Islander backgrounds visa holders from non-English speaking Students with Maori or Pacific Islander Students with a backgrounds refugee background Australian citizens or Students of Australian residents returning from South Sea islander abroad having lived for background extended periods of time in countries where their schooling was not in English Children born in Australia of migrant heritage where Children of deaf adults who use English is not spoken at home Auslan as their first language International students from non-English speaking countries Not all students from these backgrounds will require additional support to meet the curriculum expectations for their age cohort. Our school is rich in linguistic diversity from Local Aboriginal dialects to International languages with over 40 valued and spoken. We need to understand your student’s language skills as a foundation for their literacy development and engagement with the curriculum. Our English Other Language (EAL/D) classes promote: Self awareness of language and literacy skills Monitoring of language development Intensive teaching for beginners Independence Intentional and explicit teaching of Standard Australian English High Expectations Setting Goals When schools know students speak other languages they can support students in engaging in their learning to reach their educational potential. The information on these questions allows for the right support for your student. -

Convergence and Divergence in Language Contact Situations

Sonderforschungsbereich Mehrsprachigkeit International Colloquium on Convergence and Divergence in Language Contact Situations 18–20 October 2007 University of Hamburg Research Centre on Multilingualism Welcome On behalf of our Research Centre on Multilingualism (Sonderforschungsbereich Mehrsprachigkeit), generously supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) and the University of Hamburg, we would like to welcome you all here in Hamburg. This colloquium deals with issues related to convergence and divergence in language contact situations, issues which had been rather neglected in the past but have received much more attention in recent years. Five speakers from different countries have kindly accepted our invitation to share their expertise with us by presenting their research related to the theme of this colloquium. (One colleague from the US fell seriously ill and deeply regrets not being able to join us. Unfortunately, another invited speak- er cancelled his talk only two weeks ago.) All the other presentations are re- ports from ongoing work in the (now altogether 18) research projects in our centre. We hope that the three conference days will be informative and stimulating for all of us, and that the colloquium will be remembered for both its friendly atmosphere and its lively, controversial discussions. The organising commit- tee has done its best to ensure that this meeting with renowned colleagues from abroad will be a good place to make new friends or reinforce long-stand- ing professional contacts. There will be many opportunities for doing that – during the coffee breaks and especially during the conference dinner at an ex- cellent French restaurant on Thursday evening. -

The Be (Video)

CRACKERJACK EDUCATION — TEACHING WITH AUNTY Year 6 Knowledge area: Dreaming TEACHING NOTES The Be (Video) Text type: narrative, spoken, online, multimodal VISUAL STIMULUS FOCUS The Be is one of twelve ancient Dreaming stories, each story uniquely interpreted by contemporary animators, musicians, artists, writers and actors. It explores kinship and identification with a community through language, song and dance. PRIOR TO VIEWING Introduce the video The Be to students. Start the video on the website. To engage your students, pause the animation after the first 10 seconds to show the initial first frame of the story and ask the students to identify the landscape or setting. (Answer: It is set in the desert. Ask the students how they know it is the desert.) Ask the students to think about what clues the first frame of the animation gives about the type of story it is. Ask the students to predict who or what they think ‘The Be’ might be. Background • The Be is an animated Dreaming story • At the time of European colonisation there and is part of the Dust Echoes video series were hundreds of different traditional Aboriginal produced by the ABC. The story explores languages and several geographically defined kinship and identification with a community. Torres Strait Islander languages spoken in It includes full narration to assist teachers Australia.1 with enunciation of language words and • Historically, clan groups could speak not only songs, and introduces Aboriginal language to their own language but also the language students. belonging to their neighbours. This was very • The Be is a Yirritja (Year-rit-cha) story told in important when trade and travel occurred Dalabon (Dal-a-bon) language from Central across traditional language boundaries.2 Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UM l films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UME a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy, ffigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UM l directly to order. UMl A Bell & Howell Infoimation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Velar-Initial Etyma and Issues in Comparative Pama-Nyungan by Susan Ann Fitzgerald B.A.. University of V ictoria. 1989 VI.A. -

Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania

Abstract of http://www.uog.ac.pg/glec/thesis/ch1web/ABSTRACT.htm Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania by Glendon A. Lean In modern technological societies we take the existence of numbers and the act of counting for granted: they occur in most everyday activities. They are regarded as being sufficiently important to warrant their occupying a substantial part of the primary school curriculum. Most of us, however, would find it difficult to answer with any authority several basic questions about number and counting. For example, how and when did numbers arise in human cultures: are they relatively recent inventions or are they an ancient feature of language? Is counting an important part of all cultures or only of some? Do all cultures count in essentially the same ways? In English, for example, we use what is known as a base 10 counting system and this is true of other European languages. Indeed our view of counting and number tends to be very much a Eurocentric one and yet the large majority the languages spoken in the world - about 4500 - are not European in nature but are the languages of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas. If we take these into account we obtain a quite different picture of counting systems from that of the Eurocentric view. This study, which attempts to answer these questions, is the culmination of more than twenty years on the counting systems of the indigenous and largely unwritten languages of the Pacific region and it involved extensive fieldwork as well as the consultation of published and rare unpublished sources. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island).