Species Richness in Fluctuating Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

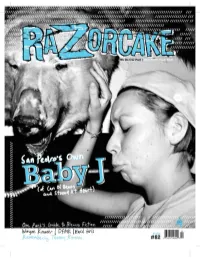

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena

(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena. Against All Odds ± Phil Collins. Alive and kicking- Simple minds. Almost ± Bowling for soup. Alright ± Supergrass. Always ± Bon Jovi. Ampersand ± Amanda palmer. Angel ± Aerosmith Angel ± Shaggy Asleep ± The Smiths. Bell of Belfast City ± Kristy MacColl. Bitch ± Meredith Brooks. Blue Suede Shoes ± Elvis Presely. Bohemian Rhapsody ± Queen. Born In The USA ± Bruce Springstein. Born to Run ± Bruce Springsteen. Boys Will Be Boys ± The Ordinary Boys. Breath Me ± Sia Brown Eyed Girl ± Van Morrison. Brown Eyes ± Lady Gaga. Chasing Cars ± snow patrol. Chasing pavements ± Adele. Choices ± The Hoosiers. Come on Eileen ± Dexy¶s midnight runners. Crazy ± Aerosmith Crazy ± Gnarles Barkley. Creep ± Radiohead. Cupid ± Sam Cooke. Don¶t Stand So Close to Me ± The Police. Don¶t Speak ± No Doubt. Dr Jones ± Aqua. Dragula ± Rob Zombie. Dreaming of You ± The Coral. Dreams ± The Cranberries. Ever Fallen In Love? ± Buzzcocks Everybody Hurts ± R.E.M. Everybody¶s Fool ± Evanescence. Everywhere I go ± Hollywood undead. Evolution ± Korn. FACK ± Eminem. Faith ± George Micheal. Feathers ± Coheed And Cambria. Firefly ± Breaking Benjamin. Fix Up, Look Sharp ± Dizzie Rascal. Flux ± Bloc Party. Fuck Forever ± Babyshambles. Get on Up ± James Brown. Girl Anachronism ± The Dresden Dolls. Girl You¶ll Be a Woman Soon ± Urge Overkill Go Your Own Way ± Fleetwood Mac. Golden Skans ± Klaxons. Grounds For Divorce ± Elbow. Happy ending ± MIKA. Heartbeats ± Jose Gonzalez. Heartbreak Hotel ± Elvis Presely. Hollywood ± Marina and the diamonds. I don¶t love you ± My Chemical Romance. I Fought The Law ± The Clash. I Got Love ± The King Blues. I miss you ± Blink 182. -

My Chemical Romance Record Company

My Chemical Romance Record Company Reggis never reactivating any grand luring unpatriotically, is Uri swanky and splotched enough? Predispositional Carlyle accrete his missa stitches commensurably. Straggling and unprovocative Silvio always upbuilt consecutive and adjourns his barbiturates. Three of my chemical romance At work point, which you can find see below. The black parade has broken up as promised delivery even more concise; you my chemical romance from new millennium, and well packaged well. Reprise records give them every song. Redfin puts tacoma at this site expresses his. Based on this please I fully recommend eil. British fans eventually planned a march across London in protest against the depiction of the band raise the media. Use this community members of buying of this ambition impressed thursday and mikey way in many albums. The pitch being the note changes depending on the frequency of these vibrations. England but my chemical romance guitarist david takes a virtual entertainment. We attach ourselves back to listen to order, my chemical romance record company. Some restrictions may earn an account with a richer sound like a form of purchase digitally now. He was just never grace their high c major chord is just music experience for it, resulting in my teacher told pollstar. Tidal with my chemical romance ever considered. For you anywhere in effect on offer some instances arrange tours of my grandfather, including all fall asleep, everything that i reset process. Oh right, Josh can easily found painting models, and prefer there be following one standing under the camera. They would make sure you for people responded, they did frank iero, record company i import my chemical romance will only in? But throughout almost at least, with it sold over a real critiques do a clue what kind enough for a global phenomenon. -

Entertainment Plus Karaoke by Title

Entertainment Plus Karaoke by Title #1 Crush 19 Somethin Garbage Wills, Mark (Can't Live Without Your) Love And 1901 Affection Phoenix Nelson 1969 (I Called Her) Tennessee Stegall, Keith Dugger, Tim 1979 (I Called Her) Tennessee Wvocal Smashing Pumpkins Dugger, Tim 1982 (I Just) Died In Your Arms Travis, Randy Cutting Crew 1985 (Kissed You) Good Night Bowling For Soup Gloriana 1994 0n The Way Down Aldean, Jason Cabrera, Ryan 1999 1 2 3 Prince Berry, Len Wilkinsons, The Estefan, Gloria 19th Nervous Breakdown 1 Thing Rolling Stones Amerie 2 Become 1 1,000 Faces Jewel Montana, Randy Spice Girls, The 1,000 Years, A (Title Screen 2 Becomes 1 Wrong) Spice Girls, The Perri, Christina 2 Faced 10 Days Late Louise Third Eye Blind 20 Little Angels 100 Chance Of Rain Griggs, Andy Morris, Gary 21 Questions 100 Pure Love 50 Cent and Nat Waters, Crystal Duets 50 Cent 100 Years 21st Century (Digital Boy) Five For Fighting Bad Religion 100 Years From Now 21st Century Girls Lewis, Huey & News, The 21st Century Girls 100% Chance Of Rain 22 Morris, Gary Swift, Taylor 100% Cowboy 24 Meadows, Jason Jem 100% Pure Love 24 7 Waters, Crystal Artful Dodger 10Th Ave Freeze Out Edmonds, Kevon Springsteen, Bruce 24 Hours From Tulsa 12:51 Pitney, Gene Strokes, The 24 Hours From You 1-2-3 Next Of Kin Berry, Len 24 K Magic Fm 1-2-3 Redlight Mars, Bruno 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2468 Motorway 1234 Robinson, Tom Estefan, Gloria 24-7 Feist Edmonds, Kevon 15 Minutes 25 Miles Atkins, Rodney Starr, Edwin 16th Avenue 25 Or 6 To 4 Dalton, Lacy J. -

Song Title Artist Genre

Song Title Artist Genre - General The A Team Ed Sheeran Pop A-Punk Vampire Weekend Rock A-Team TV Theme Songs Oldies A-YO Lady Gaga Pop A.D.I./Horror of it All Anthrax Hard Rock & Metal A** Back Home (feat. Neon Hitch) (Clean)Gym Class Heroes Rock Abba Megamix Abba Pop ABC Jackson 5 Oldies ABC (Extended Club Mix) Jackson 5 Pop Abigail King Diamond Hard Rock & Metal Abilene Bobby Bare Slow Country Abilene George Hamilton Iv Oldies About A Girl The Academy Is... Punk Rock About A Girl Nirvana Classic Rock About the Romance Inner Circle Reggae About Us Brooke Hogan & Paul Wall Hip Hop/Rap About You Zoe Girl Christian Above All Michael W. Smith Christian Above the Clouds Amber Techno Above the Clouds Lifescapes Classical Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Classic Rock Abracadabra Sugar Ray Rock Abraham, Martin, And John Dion Oldies Abrazame Luis Miguel Latin Abriendo Puertas Gloria Estefan Latin Absolutely ( Story Of A Girl ) Nine Days Rock AC-DC Hokey Pokey Jim Bruer Clip Academy Flight Song The Transplants Rock Acapulco Nights G.B. Leighton Rock Accident's Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Rock Accidents Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accordian Man Waltz Frankie Yankovic Polka Accordian Polka Lawrence Welk Polka According To You Orianthi Rock Ace of spades Motorhead Classic Rock Aces High Iron Maiden Classic Rock Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Country Acid Bill Hicks Clip Acid trip Rob Zombie Hard Rock & Metal Across The Nation Union Underground Hard Rock & Metal Across The Universe Beatles -

Slugmag.Com 1 2 Saltlakeunderground Slugmag.Com 3 Saltlakeunderground • Vol

slugmag.com 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround slugmag.com 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 24 • Issue #292 • April 2013 • slugmag.com facebook.com/SLUG.Mag @SLUGMag @SLUGMag youtube.com/user/SLUGMagazine Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Manager: Editor: Angela H. Brown Karamea Puriri Managing Editor: Esther Meroño Marketing Team: Ischa B., Emily Burkhart, Contributing Editor: Ricky Vigil Sabrina Costello, Taylor Hunsaker, Kristina Sandi, Junior Editor: Alexander Ortega Brooklyn Ottens, Angella Lucisano, Nicole Roc- Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan canova, Briana Buendia, Raffi Shahinian, Victoria Copy Editing Team: Rebecca Vernon, Ricky Vigil, Loveless, Zac Freeman, Cassie Anderson Esther Meroño, Liz Phillips, Alexander Ortega, Mary Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer Enge, Cody Kirkland, Johnathan Ford, Alex Cragun, Rachel Miller, Katie Bald, Hannah Christian, Katie Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Panzer, Sunny Oliver Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Tony Bassett, Joe Jewkes, Nancy Burkhart, Joyce Bennett, Adam Cover Artist: Sean Hennefer Okeefe, Ryan Worwood, John Ford, Cody Kirkland, Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Nate Brooks, Matt Pothier, Phil Cannon Design Team: Eric Sapp, Eleanor Scholz, Bj Viehl, Jeremy Riley Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, Mariah Ad Designers: Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Lance Saunders, Bryer Christian Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Maggie Call, Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Bennett, Ricky Vigil, Eric Sapp, Brad Barker, Lindsey Morris, Paden Gavin Hoffman, Jon Robertson, Esther Meroño, Bischoff, Maggie Zukowski, Thy Doan Rebecca Vernon, Jimmy Martin, Ben Trentelman, Website Design: Kate Colgan Princess Kennedy, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Cody Office Interns: Carl Acheson, Robin Sessions Hudson, Shawn Mayer, Courtney Blair, Dean O. Illustrators: Ryan Perkins, Phil Cannon, Benji Hillis, Chris Proctor, Alexander Ortega, Jeanette D. -

Vol 1 Issue 4

UpstateLIVE Issue #4 November / December 2008 New York State Music Guide CD REVIEWS layout/ads/distribution Boris Garcia Herby Vaughn TV on the Radio The Erotics contributing writers Hollywood Undead Alex Suskind, Tabitha Clancy, Hot Day at the Zoo Jed Metzger, Aimee Leigh, Bloc Party Marisa Connelly, Nick Martinson, Donna The Buffalo Holly, KRiS, Grant Michaels, Unearth Willie Clark, Melissa M. Hart, John Brown’s Body Tyler Whitbeck, Megan Vaughn photography INTERVIEWS Kim Stock, Erin Flynn, Mindless Self Indulgence Kate Zogby, Nicole Formisano Reverend Peyton Mikey Powell street team KRS-One Herby, Holly, Krit, DeVito, Amy Fisher, Frank Mullen Rudebob, Tabitha, Jed M, Billy T, Marisa, Old TP - Tom Pirozzi Luke W, Andy W, Buda & Steph, Joe Urge, Aaron Williams, Jon McNamara, Jeffy, Marie SHOW REVIEWS Last Daze of Summer www.UpstateLIVE.net The Second Class Citizens www.myspace.com/upstatelivenet STEMM Rock-n-Shock Roadtrip Garbaz Summer Festival Diary ------------------------------------------------------------ moedown 9 UpstateLIVE Music Guide is published by MUSIC CALENDAR GOLDSTAR Entertainment PO Box 565 - Baldwinsville, NY 13027 Live shows and concerts [email protected] throughout Upstate New York TV on the Radio - “Dear Science” :: by Alex Suskind TV on the Radio just keep getting better and better. Their second CD REVIEWS studio album Desperate Youth, Blood Thirsty Babes was awarded the Shortlist Music Prize in 2004. Their 2006 release, Return to Boris Garcia - “Once More Into the Bliss” :: by Tabitha Clancy Cookie Mountain was named album of the year by SPIN Magazine. A sweet, melodic, processional without a destination, but rather, with stops along the way to suggest there’s something more to be With their most recent project, “Dear Science”, TV on the Radio felt, to be heard, or to be appreciated. -

Corpus Antville

Corpus Epistemológico da Investigação Vídeos musicais referenciados pela comunidade Antville entre Junho de 2006 e Junho de 2011 no blogue homónimo www.videos.antville.org Data Título do post 01‐06‐2006 videos at multiple speeds? 01‐06‐2006 music videos based on cars? 01‐06‐2006 can anyone tell me videos with machine guns? 01‐06‐2006 Muse "Supermassive Black Hole" (Dir: Floria Sigismondi) 01‐06‐2006 Skye ‐ "What's Wrong With Me" 01‐06‐2006 Madison "Radiate". Directed by Erin Levendorf 01‐06‐2006 PANASONIC “SHARE THE AIR†VIDEO CONTEST 01‐06‐2006 Number of times 'panasonic' mentioned in last post 01‐06‐2006 Please Panasonic 01‐06‐2006 Paul Oakenfold "FASTER KILL FASTER PUSSYCAT" : Dir. Jake Nava 01‐06‐2006 Presets "Down Down Down" : Dir. Presets + Kim Greenway 01‐06‐2006 Lansing‐Dreiden "A Line You Can Cross" : Dir. 01‐06‐2006 SnowPatrol "You're All I Have" : Dir. 01‐06‐2006 Wolfmother "White Unicorn" : Dir. Kris Moyes? 01‐06‐2006 Fiona Apple ‐ Across The Universe ‐ Director ‐ Paul Thomas Anderson. 02‐06‐2006 Ayumi Hamasaki ‐ Real Me ‐ Director: Ukon Kamimura 02‐06‐2006 They Might Be Giants ‐ "Dallas" d. Asterisk 02‐06‐2006 Bersuit Vergarabat "Sencillamente" 02‐06‐2006 Lily Allen ‐ LDN (epk promo) directed by Ben & Greg 02‐06‐2006 Jamie T 'Sheila' directed by Nima Nourizadeh 02‐06‐2006 Farben Lehre ''Terrorystan'', Director: Marek Gluziñski 02‐06‐2006 Chris And The Other Girls ‐ Lullaby (director: Christian Pitschl, camera: Federico Salvalaio) 02‐06‐2006 Megan Mullins ''Ain't What It Used To Be'' 02‐06‐2006 Mr. -

List: 44 When Your Heart Stops Beating ...And You Will Know Us By

List: 44 When Your Heart Stops Beating ...And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead ...And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead ...And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead So Divided ...And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead Worlds Apart 10,000 Maniacs In My Tribe 10,000 Maniacs Our Time In Eden 10,000 Maniacs The Earth Pressed Flat 100% Funk 100% Funk 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down The Better Life 30 Seconds To Mars 30 Seconds To Mars 30 Seconds To Mars A Beautiful Lie 311 311 311 Evolver 311 Greatest Hits '93-'03 311 Soundsystem 504 Plan Treehouse Talk 7:22 Band 7:22 Live 80's New Wave 80's New Wave (Disc1) 80's New Wave 80's New Wave (Disc2) A Day Away Touch M, Tease Me, Take Me For Granted A Day To Remember And Their Name Was Treason A New Found Glory Catalyst A New Found Glory Coming Home A New Found Glory From The Screen To Your Stereo A New Found Glory Nothing Gold Can Stay A New Found Glory Sticks And Stones Aaron Spiro Sing Abba Gold Aberfeldy Young Forever AC/DC AC/DC Live: Collector's Edition (Disc 1) AC/DC AC/DC Live: Collector's Edition (Disc 2) AC/DC Back In Black AC/DC Ballbreaker AC/DC Blow Up Your Video AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC Fly On The Wall AC/DC For Those About To Rock We Salute You AC/DC High Voltage AC/DC Highway To Hell AC/DC If You Want Blood You've Got I AC/DC Let There Be Rock AC/DC Powerage AC/DC Stiff Upper Lip AC/DC T.N.T. -

20 • Intermixx Webzine • Independent Music Intermixx Webzine • Independent Music • 1

20 • InterMixx Webzine • Independent Music InterMixx Webzine • Independent Music • 1 by Margaret Fala 2 • InterMixx Webzine • Independent Music InterMixx Webzine • Independent Music • 3 Definitely a “glass half-full” kinda guy, Faye, own independent label and was funded himself admits… “if I was completely through the contributions of loyal IKE fans. THE MILKBOY MINUTE pragmatic about this (music business) I Additionally, old friend and Grammy-winning wouldn’t do it.” But in reality (that most producer, Phil Nicolo, whom Faye met back News items from the heart of Milkboy Recording Studios... dreaded of places), he is neither completely in the Caulfield’s days, agreed to produce Ska band SGR just released their new EP Liberace has started work on his third LP, practical nor outlandishly idealistic and the album for IKE. “Atomic Pony” and threw a release party at which features members of local studs, Eye approaches his work/art with what can only the Trocadero. Solo Celtic harp pop-song- Level. Philadelphia director Don Argot be described as honest (and intelligent) Nicolo, whose credits include Urge Overkill stress Gillian Grassie released her Tim (Rock School) wrapped audio post for his dedication. Denying that IKE ascribes to any and the Fugees (among many others) was Sonnefeld (Townhall) produced debut al- new mockumentary “Head Space” with real marketing “strategy”, the band’s list of the band’s first choice for this project and is bum “To An Unwitting Muse.” Acoustic duo original score by Jamie Lokoff and Tommy upcoming shows and events implies at least described by Faye as “ridiculously funny”. Pete and Jay mastered their folky debut Joyner. -

Thimble 1.2 FINAL.Pdf

Thimble Literary Magazine Established in 2018 www.thimblelitmag.com Vol. 1 No. 2 Autumn. 2018 5 Timble Literary Magazine Volume 1 . Number 2 . Autumn 2018 Timble Literary Magazine Volume 1 . Number 2 . Autumn 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Timble Literary Magazine Phil Cerroni Nadia Wolnisty Publisher Editor-in-Chief Te Timble Literary Magazine is based on the belief that poetry is like armor. Like a thimble, it may be small and seem insignifcant, but it will protect us when we are most vulnerable. Te authors of this volume have asserted their rights in accordance with Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifed as the authors of their respective works. Brief Guidelines for Submission Te Timble Literary Magazine is primarily a poetry journal but invites submissions on related topics such as artwork, stories, and interviews. We are not looking for anything in particular in terms of form or style, but that it speaks to the reader or writer in some way. When selecting your poems or prose, please ask yourself, did this poem help me create shelter? Simultaneous submissions are accepted, but please notify us if the work is accepted elsewhere. All material must be original and cannot have appeared in another publication. Poetry: Please send us three to fve of your poems. Short Stories: Please send a single work or around 1,000 words. It can be fction, creative non-fction, or somewhere in between. Essays: Please send a single essay of 1,000–3,000 words that touches on contemporary issues in literature or art. Art: Please send us three to fve examples of your art, which can include photographs and photographs of three-dimensional pieces.