Locomotive Blast Pipes and Ch Imn Eys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 155 Spring 2012

NEWSLETTER 155 SPRING 2012 Puddlers’ Bridge on the Trevithick Trail, near Merthyr Tydfil. Reg. Charity 1 No. 246586 CHAIRMAN’S ADDRESS Creating links The recent opening of the Sustrans bridge, covered elsewhere in this issue, to connect two lengths of the Trevithick Trail near Merthyr Tydfil came about a year after the University of Swansea published an investigation into the Welsh Copper Industry.* Both these significant events in industrial history depended upon Cornwall’s links with Wales. In the first instance, Richard Trevithick’s ingenuity and development of the high- pressure steam engine in Cornwall took form as the world’s first steam powered railway locomotive in Wales. It is well known for having pulled a train loaded with 10 tons of iron and some 70 passengers nearly ten miles. This was 25 years before the emergence of George Stephenson’s Rocket. The second event depended mainly on the little sailing ships that carried thousands of tons of copper ore from Cornwall and returned with the Welsh coal and iron that powered Cornwall’s mines and fed its industries. Investigations have shown that much of the copper smelting in Wales and shipping was controlled by Cornish families. Cornwall had similar industrial links to Bridgnorth, Dartford and other places throughout the country; all depended to a great extent upon Cornish ingenuity. This Society appears to be the only link today between Cornwall’s industrial archaeology and that of other parts of the country. If we are to encourage the study of Cornwall’s industrial archaeology we need to develop these links for the benefit of all concerned, wherever they may be. -

Newsletter 180 Summer 2018

NEWSLETTER 180 SUMMER 2018 Robert Metcalfe leading the AGM weekend walk around Wheal Owles. Reg. Charity 1 No. 1,159,639 the central machinery hall, and consists of REPUTED TREVITHICK a single-cylinder return crank engine of the ENGINE vertical type, which there is every reason to consider it being one of Richard Trevithick’s design. Whilst it bears no maker’s name nor any means of direct identification, it presents so many well-known Trevithick features that it may be pretty certainly set down as a product of the ingenuity of the Father of High-pressure Steam. The engine was employed for over fifty years, down to 1882, at some salt works at Ingestre, Staffordshire, on the Earl’s estate. Prior to that it had been used for the winding at a colliery at Brereton, near Rugeley, and is thought to have been built at Bridgnorth. It is known that Haseldine and Co, of that place, built many engines to Trevithick’s design, under agreement with him. The engine is somewhat later than the other examples of his, close by, and is therefore of peculiar interest in enabling the course of gradual improvement to be easily followed. Thanks to Peter Coulls, the Almost everything about the request for a copy of The Engineer article machine is of cast iron, and probably its (Volume 113, page 660 (21st June 1912) original boiler was too. This, however, had about the mystery Reputed Trevithick long disappeared - they generally burst High-pressure Engine was successful. A - steam having been supplied at Ingestre copy of the article promptly arrived in the by an egg-ended boiler, 8.5 ft long by post and is reproduced here in full: 3 ft in diameter, set with a partial wheel draught and working at 35 lb pressure. -

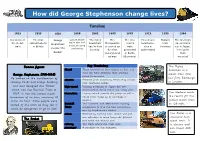

How Did George Stephenson Change Lives?

How did George Stephenson change lives? Timeline 1812 1825 1829 1850 1863 1863 1879 1912 1938 1964 Invention of The first George Luxury steam ‘The flying The The first First diesel Mallard The first high trains with soft the steam railroad opens Stephenson Scotsman’ Metropolitan electric locomotive train speed trains train in Britain seats, sleeping had its first is opened as train runs in invented run in Japan. invents ‘The and dining journey. the first presented Switzerland ‘The bullet Rocket’ underground in Berlin train railway (Germany) invented’ Key Vocabulary Famous figures The Flying diesel These locomotives burn diesel as fuel and Scotsman is a were far more powerful than previous George Stephenson (1781-1848) steam train that steam locomotives. He worked on the development of ran from Edinburgh electric Powered from electricity which they collect to London. railway tracks and bridge building from overhead cables. and also designed the ‘Rocket’ high-speed Initially produced in Japan but now which won the Rainhill Trials in international, these trains are really fast. The Mallard holds 1829. It was the fastest steam locomotive Engines which provide the power to pull a the record for the locomotive of its time, reaching 30 whole train made up of carriages or fastest steam train miles an hour. Some people were wagons. Rainhill The Liverpool and Manchester railway at 126 mph. scared of the train as they felt it Trials competition to find the best locomotive, could be dangerous to go so fast! won by Stephenson’s Rocket. steam Powered by burning coal. Steam was fed The Bullet is a into cylinders to move long rods (pistons) Japanese high The Rocket and make the wheels turn. -

History of the Automobile

HISTORY OF THE AUTOMOBILE Worked by: Lara Mateus nº17 10º2 Laura Correia nº18 10º2 Leg1: the first car. THE EARLY HISTORY The early history of the automobile can be divided into a number of eras, based on the prevalent means of propulsion. Later periods were defined by trends in exterior styling, size, and utility preferences. In 1769 the first steam powered auto-mobile capable of human transportation was built by Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot. In 1807, François Isaac de Rivaz designed the first car powered by an internal combustion engine fueled by hydrogen. In 1886 the first petrol or gasoline powered automobile the Benz Patent-Motorwagen was invented by Karl Benz.This is also considered to be the first "production" vehicle as Benz made several identical copies. FERDINAND VERBIEST Ferdinand Verbiest, a member of a Jesuit mission in China, built the first steam-powered vehicle around 1672 as a toy for the Chinese Emperor. It was of small enough scale that it could not carry a driver but it was, quite possibly the first working steam-powered vehicle. Leg2: Ferdinand Verbiest NICOLAS-JOSEPH CUGNOT Steam-powered self-propelled vehicles large enough to transport people and cargo were first devised in the late 18th century. Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot demonstrated his fardier à vapeur ("steam dray"), an experimental steam-driven artillery tractor, in 1770 and 1771. As Cugnot's design proved to be impractical, his invention was not developed in his native France. The center of innovation shifted to Great Britain. NICOLAS-JOSEPH CUGNOT By 1784, William Murdoch had built a working model of a steam carriage in Redruth. -

The Mikado Messenger | Issue No. 66| April 2020 Ian Matthews Sanding the Filler, on the Tender Tank, Before It Is Painted

The Mikado Messenger | Issue No. 66| April 2020 Ian Matthews sanding the filler, on the tender tank, before it is painted - A1SLT Welcome to edition No. 66 of The Mikado Messenger, our monthly eNewsletter which aims to provide a regular progress update on the construction of new Gresley class No. 2007 Prince of Wales. Thanks to our supporters’ continued generosity, over £3.5m has now been donated or pledged – this equates to over 70% of the required £5m. This month see the launch of a brand new club - The Pony (Truck) Club - please see below for more information. Stephenson Engineering Ltd have sent us a fabulous video of the CNC machining programme that will be carried out on the coupling rods - it can be found in the Motion Update section, below. We are following Government guidelines with regards to the coronavirus, and whilst our office-based staff are now working from home, our workshop staff are continuing to work at Darlington Locomotive Works where they are taking all necessary precautions. However, as many of our supporters and volunteers are from vulnerable groups, the Works is currently closed to non-essential staff. In addition, Nene Valley Railway have cancelled all their events until the end of May 2020 so this means we can no longer hold the P2 Roadshow on Saturday 23rd May 2020 and the Supporters’ and Tornado Team day on Sunday 24th May 2020. We are sorry to have to make these changes. We hope you understand that the circumstances are beyond our control and the restrictions are very necessary at this challenging time. -

Lima 2-8-0 “Consolidation”, Developed for TS2013, by Smokebox

Union Pacific 4000 Class 4884-1 "Big Boy" circa 1948-49 Developed by Smokebox TM for Dovetail Games' Train Simulator © Smokebox 2021, all rights reserved Issue 1 Union Pacific 4000 Class 4884-1 "Big Boy" Steam Locomotive Page 2 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 32- and 64-bit TS ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Expert or Simple Controls mode, HUD and Automatic Fireman ....................................................................... 7 "All-in-one" .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Standard TS Automatic Fireman .................................................................................................................... 8 F4 HUD ........................................................................................................................................................... 8 High Detail (HD) and Standard Detail (SD) ........................................................................................................ 8 Recommended Settings ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Cab Layout ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Lean's Engine Reporter and the Development of The

Trans. Newcomen Soc., 77 (2007), 167–189 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Lean’s Engine Reporter and the Development of the Cornish Engine: A Reappraisal by Alessandro NUVOLARI and Bart VERSPAGEN THE ORIGINS OF LEAN’S ENGINE REPORTER A Boulton and Watt engine was first installed in Cornwall in 1776 and, from that year, Cornwall progressively became one of the British counties making the most intensive use of steam power.1 In Cornwall, steam engines were mostly employed for draining water from copper and tin mines (smaller engines, called ‘whim engines’ were also employed to draw ore to the surface). In comparison with other counties, Cornwall was characterized by a relative high price for coal which was imported from Wales by sea.2 It is not surprising then that, due to their superior fuel efficiency, Watt engines were immediately regarded as a particularly attractive proposition by Cornish mining entrepreneurs (commonly termed ‘adventurers’ in the local parlance).3 Under a typical agreement between Boulton and Watt and the Cornish mining entre- preneurs, the two partners would provide the drawings and supervise the works of erection of the engine; they would also supply some particularly important components of the engine (such as some of the valves). These expenditures would have been charged to the mine adventurers at cost (i.e. not including any profit for Boulton and Watt). In addition, the mine adventurer had to buy the other components of the engine not directly supplied by the Published by & (c) The Newcomen Society two partners and to build the engine house. -

Union Pacific No. 119

Union Pacific No. 119 Operating Manual Developed by Smokebox for Dovetail Games' Train Simulator 2018TM © Smokebox 2018, all rights reserved Issue 1 Train Simulator - Union Pacific No. 119 - Operating Manual Page 2 Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Locomotive Technical Specifications................................................................................................................. 4 Positions of the Controls and Gauges in the Cab .............................................................................................. 5 Key Assignments................................................................................................................................................ 9 Animations....................................................................................................................................................... 12 Lights................................................................................................................................................................ 13 Sanding ............................................................................................................................................................ 13 Particle Effects................................................................................................................................................. 14 Other Special Effects ...................................................................................................................................... -

HO-Scale #562 in HO-Scale – Page 35 by Thomas Lange Page 35

st 1 Quarter 2021 Volume 11 Number 1 _____________________________ On the Cover of This Issue Table Of Contents Thomas Lange Models a NYC Des-3 Modeling A NYC DES-3 in HO-Scale #562 In HO-Scale – Page 35 By Thomas Lange Page 35 Modeling The Glass Train By Dave J. Ross Page 39 A Small Midwestern Town Along A NYC Branchline By Chuck Beargie Page 44 Upgrading A Walthers Mainline Observation Car Rich Stoving Shares Photos Of His By John Fiscella Page 52 Modeling - Page 78 From Metal to Paper – Blending Buildings on the Water Level Route By Bob Shaw Page 63 Upgrading A Bowser HO-Scale K-11 By Doug Kisala Page70 Kitbashing NYCS Lots 757-S & 766-S Stockcars By Dave Mackay Page 85 Modeling NYC “Bracket Post” Signals in HO-Scale By Steve Lasher Page 89 Celebrating 50 Years as the Primer Railroad Historical Society NYCentral Modeler From the Cab 5 Extra Board 8 What’s New 17 The NYCentral Modeler focuses on providing information NYCSHS RPO 23 about modeling of the railroad in all scales. This issue NYCSHS Models 78 features articles, photos, and reviews of NYC-related Observation Car 100 models and layouts. The objective of the publication is to help members improve their ability to model the New York Central and promote modeling interests. Contact us about doing an article for us. [email protected] NYCentral Modeler 1st Qtr. 2021 2 New York Central System Historical Society The New York Central System Central Headlight, the official Historical Society (NYCSHS) was publication of the NYCSHS. -

Types and Characteristics of Locomotives Dr. Ahmed A. Khalil Steam Locomotives - Operating Principle

Types and Characteristics of Locomotives Dr. Ahmed A. Khalil Steam Locomotives - Operating Principle: The wheel is connected to the rod by a crank. The rod is connected to the piston rod of the steam cylinder., thereby converting the reciprocating motion of the piston rod generated by steam power into wheel rotation. - Main Parts of a steam locomotive: 1. Tender — Container holding both water for the boiler and combustible fuel such as wood, coal or oil for the fire box. 2. Cab — Compartment from which the engineer and fireman can control the engine and tend the firebox. 3. Whistle — Steam powered whistle, located on top of the boiler and used as a signalling and warning device. 4. Reach rod — Rod linking the reversing actuator in the cab (often a 'johnson bar') to the valve gear. 5. Safety valve — Pressure relief valve to stop the boiler exceeding the operating limit. 6. Generator — Steam powered electric generator to power pumps, head lights etc, on later locomotives. 7. Sand box/Sand dome — Holds sand that can be deposited on the rails to improve traction, especially in wet or icy conditions. 8. Throttle Lever — Controls the opening of the regulator/throttle valve thereby controlling the supply of steam to the cylinders. 9. Steam dome — Collects the steam at the top of the boiler so that it can be fed to the engine via the regulator/throttle valve. 10. Air pump — Provides air pressure for operating the brakes (train air brake system). 11. Smoke box — Collects the hot gas that have passed from the firebox and through the boiler tubes. -

O-Steam-Price-List-Mar2017.Pdf

Part # Description Package Price ======== ================================================== ========= ========== O SCALE STEAM CATALOG PARTS LIST 2 Springs, driver leaf........................ Pkg. 2 $6.25 3 Floor, cab and wood grained deck............. Ea. $14.50 4 Beam, end, front pilot w/coupler pocket...... Ea. $8.00 5 Beam, end, rear pilot w/carry iron.......... Ea. $8.00 6 Bearings, valve rocker....................... Pkg.2 $6.50 8 Coupler pockets, 3-level, for link & pin..... Pkg. 2 $5.75 9 Backhead w/fire door base.................... Ea. $9.00 10 Fire door, working........................... Ea. $7.75 11 Journal, 3/32" bore.......................... Pkg. 4. $5.75 12 Coupler pockets, small, S.F. Street Railway.. Pkg.2 $5.25 13 Brakes, engine............................... Pkg.2 $7.00 14 Smokebox, 22"OD, w/working door.............. Ea. $13.00 15 Drawbar, rear link & pin..................... Ea. $5.00 16 Handles, firedoor............................ Pkg.2. $5.00 17 Shelf, oil can, backhead..................... Ea. $5.75 18 Gauge, backhead, steam pressure.............. Ea. $5.50 19 Lubricator, triple-feed, w/bracket, Seibert.. Ea. $7.50 20 Tri-cock drain w/3 valves, backhead.......... Ea. $5.75 21 Tri-cock valves, backhead, (pl. 48461)....... Pkg. 3 $5.50 23 Throttle, nonworking......................... Ea. $6.75 23.1 Throttle, non working, plastic............... Ea. $5.50 24 Pop-off, pressure, spring & arm.............. Ea. $6.00 25 Levers, reverse/brake, working............... Kit. $7.50 26 Tri-cock drain, less valves.................. Ea. $5.75 27 Seat boxes w/backs........................... Pkg.2 $7.50 28 Injector w/piping, Penberthy,................ Pkg.2 $6.75 29 Oiler, small hand, N/S....................... Pkg.2 $6.00 32 Retainers, journal........................... Pkg. -

FLYING SCOTSMAN’ LNER 4-6-2 1:32 SCALE • 45 Mm GAUGE

‘FLYING SCOTSMAN’ LNER 4-6-2 1:32 SCALE • 45 mm GAUGE ENGINEERING SAMPLE SHOWN Sir Nigel Gresley was renowned for his Pacific express locomo- SPECIFICATIONS tives, the first of which, the A1 class, entered service in 1922. The A3 was a modification of the A1 and over time all of the sur- Scale 1:32 viving A1s were rebuilt as A3s. No. 4472 “Flying Scotsman” was Gauge 45 mm built in 1923 and went on to become one of the most famous Mini. radius 6ft 6in. (2 m) steam locomotives in the world setting many records along the way. After the war it was renumbered 103 then, after the nation- Dimensions 26.5 x 3.5 x 5.25 in. alisation, carried the number 60103, remaining in service on the Construction Brass & stainless steel East Coast mainline until 1963. During its service career it cov- Electric Version ered over 2,000,000 miles and travelled non-stop from London Power 0~24V DC to Edinburgh in 8 hours. It was sold into private ownership, was Full cab interior design sent to America and Australia and is today under restoration at Features The National Railway Museum in York. Constant lighting Live Steam Version We are currently developing a 1:32 scale live steam version of our very successful electric LNER A3 Class “Flying Scotsman”. Power Live steam, butane fired The model is gas-fired with slide valves and has all the features Boiler Copper the Gauge 1 fraternity have come to expect from an Accucraft Valve gear Walschaerts valve gear locomotive.