Ecclesiology Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bowdoin College Catalogues

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Bowdoin College Catalogues 1-1-1973 Bowdoin College Catalogue (1972-1973) Bowdoin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/course-catalogues Recommended Citation Bowdoin College, "Bowdoin College Catalogue (1972-1973)" (1973). Bowdoin College Catalogues. 254. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/course-catalogues/254 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bowdoin College Catalogues by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOWDOIN COLLEGE BULLETIN CATALOGUE FOR 1972-1973 September 1972 BOWDOIN COLLEGE BULLETIN Catalogue for 1972-1973 BRUNSWICK, MAINE 2 'Wo test with respect to race, color, creed, national origin, or sex shall be imposed in the choice of Trustees, Overseers, officers, members of the Faculty, any other employees, or in the admission ." of students. —By-Laws of Bowdoin College The information in this catalogue was accurate at the time of original publication. The College reserves the right, however, to make changes in its course offerings, degree requirements, regula- tions and procedures, and charges as educational and financial considerations require. BOWDOIN COLLEGE BULLETIN Brunswick, Maine September igy Number 386 This Bulletin is published by Bowdoin College four times during the college year: September, December, March, and June. Second-class postage paid at Brunswick, Maine. CONTENTS COLLEGE -

Saint John Henry Newman

SAINT JOHN HENRY NEWMAN Chronology 1801 Born in London Feb 21 1808 To Ealing School 1816 First conversion 1817 To Trinity College, Oxford 1822 Fellow, Oriel College 1825 Ordained Anglican priest 1828-43 Vicar, St. Mary the Virgin 1832-33 Travelled to Rome and Mediterranean 1833-45 Leader of Oxford Movement (Tractarians) 1843-46 Lived at Littlemore 1845 Received into Catholic Church 1847 Ordained Catholic priest in Rome 1848 Founded English Oratory 1852 The Achilli Trial 1854-58 Rector, Catholic University of Ireland 1859 Opened Oratory school 1864 Published Apologia pro vita sua 1877 Elected first honorary fellow, Trinity College 1879 Created cardinal by Pope Leo XIII 1885 Published last article 1888 Preached last sermon Jan 1 1889 Said last Mass on Christmas Day 1890 Died in Birmingham Aug 11 Other Personal Facts Baptized 9 Apr 1801 Father John Newman Mother Jemima Fourdrinier Siblings Charles, Francis, Harriett, Jemima, Mary Ordination (Anglican): 29 May 1825, Oxford Received into full communion with Catholic Church: 9 October 1845 Catholic Confirmation (Name: Mary): date 1 Nov 1845 Ordination (Catholic): 1 June 1847 in Rome First Mass 5 June 1847 Last Mass 25 Dec 1889 Founder Oratory of St. Philip Neri in England Created Cardinal-Deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro: 12 May 1879, in Rome, by Pope Leo XIII Motto Cor ad cor loquitur—Heart speaks to heart Epitaph Ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem—Out of shadows and images into the truth Declared Venerable: 22 January 1991 by Pope St John Paul II Beatified 19 September 2010 by Pope Benedict XVI Canonized 13 October 2019 by Pope Francis Feast Day 9 October First Approved Miracle: 2001 – healing of Deacon Jack Sullivan (spinal condition) in Boston, MA Second Approved Miracle: 2013 – healing of Melissa Villalobos (pregancy complications) in Chicago, IL Newman College at Littlemore Bronze sculpture of Newman kneeling before Fr Dominic Barberi Newman’s Library at the Birmingham Oratory . -

James Payne Profiles Sweden's Johan Celsing Martin Pearce On

BB17-1-Cover:Layout BB 10/09/2012 14:37 Page 3 B VOTE R FOR YOUR FAVOURITE SHORTLIST PROJECT I C K OVER 300 ENTRIES, OVER 80 SHORTLISTED PROJECTS AND ONLY 16 TROPHIES TO BE WON! B U L L IN AID OF E 2012 @ TH T SPONSORS -NOV 6 TH I 13TH N ARCHITECTS CHOICE AWARD NOVEMBERAUG 6 MARRIOTT GROSVENOR SQUARE HOTEL, LONDON ARCHITECTS CHOICEWWW.BRICK.ORG.UK AWARD AUGTH 6 -NOV 6 www.brick.org.uk/brick-awards/architects-choice-award/ James Payne profiles Sweden’s Johan Celsing WILL YOU BE Martin Pearce on Paul Bellot’s Quarr Abbey TH A WINNER? Königs Architects’ St Marien church in Schillig 2012 @ Hat Projects in Hastings, PRP Architects in London First person: David Kirkland of Kirkland Fraser Moor AUTUMN 2012 Expressive brick buttresses by Hild & K Architects BB17-2-Contents:Layout BB 10/09/2012 14:40 Page 2 2 • BB AUTUMN 2012 BB17-2-Contents:Layout BB 10/09/2012 14:40 Page 3 Brick Bulletin autumn 2012 contents Highs and lows 4 NEWS Left outside and unmaintained, Projects in Suffolk and The Hague; high performance cars and Brick Awards shortlist; First Person – yachts soon look rather forlorn, David Kirkland of Kirkland Fraser Moor. suggests David Kirkland, 6 PROJECTS drawing parallels between Page & Park, Henley Halebrown Rorrison, state-of-the-art components and Königs Architects, PRP Architects, Lincoln brick. Kirkland, whose practice Miles Architecture and Weston Williamson. emerged from a high-tech 14 PROFILE background, says working James Payne explores the expressive brick with brick has been a creative architecture of Johan Celsing. -

H. H. Richardson Historic District of North Easton and Or Common 2

NFS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ali entries complete appiicabie sections_______________ 1. Name historic H. H. Richardson Historic District of North Easton and or common 2. Location street & number North Easton (see continuation sheet) __ not for publication city, town North Easton vicinity of state Massachusetts code county Bristol code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use _XL_ district x public x occupied agriculture __ museum building(s) x private unoccupied __ commercial x park structure _^c_both work in progress educational J£ _ private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted x government scientific being considered - yes: unrestricted __ industrial __ transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name See Continuation Sheet street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Bristol County Registry of Deeds street & number City Hall city, town Taunton state Massachusetts 6. Representation in Existing Surveys__________ title National Register of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? ——yes ——no date 1972_________________________________ *_ federal __ state __ county __ local depository for survey records National Park Service_________________________________ _ city, town Washington state DC 7. Description Condition Check one Check one .^excellent deteriorated unaltered _J^L original site good ruins w/' altered moved date __ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance There are five Richardson buildings in this historic district: the Oliver Ames Free Library, the Oakes Ames Memorial Hall, the Gate Lodge at Langwater, the Gardener's Cottage at Langwater, and the Old Colony Railroad Station. -

Lilillliiiiiiiiiiillil COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY of DEEDS

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE M/v p p n.r» ftn p p -h +: p COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Suffolk INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (lype all entries — complete applicable sections) ^^Pi^^^^^ffi^SiiMliiii^s»^«^^i^ilSi COMMON: •••'.Trv; ;.fY ', ; O °. • ':'>•.' '. ' "'.M'.'.X; ' -• ."":•:''. Trinity Church "' :: ' ^ "' :; " ' \.'V 1.3 ' AND/OR HISTORIC: Trinity EpisQppa^L Church W&££$ii$$®^^ k®&M$^mmmmmmm:^^ STREET AND NUMBER: Boylston Street, at Coplev Sauare CITY OR TOWN: "Rofiton STATE CODE COUNTY: CODE Ma. ft ft an h n ft P i". t s Snffnlk STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Q District g] Building d P " D| i c Public Acquisition: ^ Occupied Yes: ., . , | | Restricted Q Site Q Structure H Private D 1" Process a Unoccupied ' — i— i D • i0 Unrestricted Q Object D Both D Being Considered [_J Preservation work in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ I Agricultural | | Government 1 1 Park I | Transportation 1 1 Comments | | Commercial 1 1 Industrial | | Private Residence I"") Other (Specify) | | Educational 1 1 Military [X] Religious | | Entertainment 1 1 Museum | | Scientific ................. OWNER'S NAME: (/> Reverend Theodore Park Ferris, Rector, Trinity Epsicopal Ch'urch STREET AND NUMBER: CJTY OR TOWN: ' STAT E: 1 CODE Boston 02 II1-! I lassachusetts. , J fillilillliiiiiiiiiiillil COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: COUNTY: Registry of Deeds, Suffolk County STREET AND NUMBER: -

Download File

CANON: ENGLISH ANTECEDENTS OF THE QUEEN ANNE IN AMERICA 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I would like to thank my thesis advisor Janet W. Foster, adjunct assistant professor, Columbia University, for her endless positivity and guidance throughout the process. We share an appreciation for late nineteenth century American architecture and I feel very grateful to have worked with an advisor who is an expert on the period of time explored in this work. I would also like to thank my readers Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, professor, University of Washington, and Andrew Saint, author, for their time and assistance. Professor Ochsner thank you for your genuine interest in the topic and for contributing your expertise on nineteenth century American architecture, Henry Hobson Richardson and the Sherman house. Andrew thank you for providing an English perspective and for your true appreciation for the “Old English.” You are the expert on Richard Norman Shaw and your insight was invaluable in understanding Shaw’s works. This work would not have come to fruition without the insight and interest of a number of individuals in the topic. Thank you Sarah Bradford Landau for donating many of the books used in this thesis and whose article “Richard Morris Hunt, the Continental Picturesque and the ‘Stick Style’” was part of the inspiration for writing this thesis, and as this work follows where your article concluded. Furthermore, I would like to thank Andrew Dolkart, professor, Columbia University, for your recommendations on books to read and places to see in England, which guided the initial ideas for the thesis. There were many individuals who offered their time, assistance and expertise, thank you to: Paul Bentel, adjunct professor, Columbia University Chip Bohl, architect, Annapolis, Maryland Françoise Bollack, adjunct professor, Columbia University David W. -

Church of Saint Michael

WLOPEFM QFJBPJBP Church of Saint Michael Saturday: 4:30PM God's sons and daughters in Sunday: 8:00AM, 10:30AM Tuesday: 6:30PM Chapel Farmington, Minnesota Wednesday: 8:30AM Chapel Thursday: 8:30AM Chapel Our Mission Friday: 8:30AM Chapel To be a welcoming Catholic community CLKCBPPFLKLK centered in the Eucharist, inving all to live the Saturday: 3:15-4:15PM Gospel and grow in faith. AKLFKQFKD LC QEB SF@HF@H If you or a family member needs to October 20, 2019—World Mission Sunday receive the Sacrament of Anoinng please call the parish office, 651-463-3360. B>MQFPJJ Bapsm class aendance is required. Bapsm I is offered the 3rd Thursday of the month at 7pm. Bapsm II is offered the 2nd Thursday of the month at 6:30pm. Group Bapsm is held the 2nd Sunday of the month at 12:00noon. (Schedule can vary) Email [email protected] or call 651-463-5257. M>QOFJLKVLKV Please contact the Parish Office. Allow at least 9 months to prepare for the Sacrament of Marriage. HLJB?LRKA ER@E>OFPQFPQ If you or someone you know is homebound and would like to receive Holy Communion, please contact Jennifer Schneider 651-463-5224. PO>VBO LFKBFKB Email your prayer requests to: [email protected] or call 651-463-5224 P>OFPE OCCF@B HLROPROP Monday through Friday 8:00am-4:00pm Phone—651-463-3360 [email protected] BRIIBQFK DB>AIFKBFKB Monday noon for the following Sunday bullen, submit to: info@stmichael- farmington.org 22120 Denmark Avenue—Farmington MN 55024—www.stmichael-farmington.org ▪ October 20, 2019 2 From the Pastor THAT CHRIST MAY DWELL IN YOUR 4:30 PM Mass and to bless our sanctuary crucifix. -

Study Report Proposed H. H. Richardson Depot Historic District Framingham, Massachusetts

Study Report Proposed H. H. Richardson Depot Historic District Framingham, Massachusetts Framingham Historic District Commission Community Opportunities Group, Inc. September 2016 Study Report Proposed H. H. Richardson Depot Historic District September 2016 Contents Summary Sheet ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Public Hearings and Town Meeting ..................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Background to the Current Proposal ................................................................................................ 5 Local Historic Districts and the Historic Districts Act ................................................................... 6 Local Historic Districts vs. National Register Districts .................................................................. 7 Methodology Statement ........................................................................................................................ 8 Significance Statement ......................................................................................................................... 9 Historical Significance ..................................................................................................................... 9 Architectural Description .............................................................................................................. -

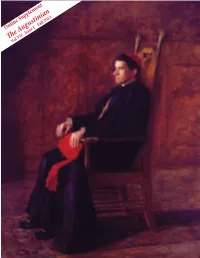

The Augustinian Vol VII

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St. -

Henry Hobson Richardson Article.9-5

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Henry Hobson Richardson Ever had the unfortunate experience of ordering an “Old-Fashioned” and discovering that the bartender added soda to it? Still, soda water is a necessary additive to many cocktails, where its purpose is to extend the drink and provide that sparkling “fizz”. This process of diluting “short” drinks (such as spirits) makes them “long”, and the presence of carbon dioxide in a cocktail may actually speed up the absorbtion of alcohol into the blood. In southern and tropical colonial areas, the addition of carbonated water to dilute spirits was quite prevalent in hot climates and viewed as a rather “British” habit. This was especially true with gin and the addition of tonic (or Indian tonic water), which is carbonated water with quinine added. And soda water is, after all, the essential ingredient of a multitude of soft drinks, which is what they’re called in New Orleans (as well as “cold drinks”). In the rest of the country, they mostly say “sodas”. All of this would not have been possible without the fertile scientific mind of Joseph Priestley (1733 – 1804) who invented soda water in 1767 by discovering a means of infusing water with carbon dioxide at a brewery in Leeds, England. The “fixed air” (carbon dioxide gas) blanketing the fermenting beer was known to kill mice, but Priestley found that (by impregnating the water with this “fixed air”) he had created a pleasant tasting and refreshing beverage. He produced the “fixed air” by dripping sulfuric acid onto chalk, which he encouraged to dissolve into an agitated bowl of water. -

27Th Sunday in Ordinary Time Weekend 3Rd / 4Th October 2020

OUR LADY IMMACULATE & ST MICHAEL, BATTLE with ST TERESA OF LISIEUX, HORNS CROSS 14 Mount Street, Battle, East Sussex, TN33 0EG Tel: 01424 773125 e-mail: [email protected] website: battlewithnorthiam.parishportal.net Parish Priest: Fr Anthony White Weekend Mass Times Cycle A for Sundays and Solemnities 6pm Saturday 3rd October Year 2 for Weekdays – Battle (Stephen & Kenneth Arundel and Brighton Trust is a McAdie, RIP) Registered Charity No. 252878 9am Sunday 4th October – Northiam (Terry Evans RIP) Private Prayer Sessions - Battle 10.45am Sunday 4th October Monday, Wednesday – Battle (David Reynders RIP) Friday 10am – 11am Sacrament of Reconciliation th after 6pm Mass Saturdays 27 Sunday in Ordinary Time rd th Weekend 3 / 4 October 2020 • When You Join Us at Mass this Weekend So that we can all feel safe, please observe the instructions of the stewards, and ensure that you wear a face covering at all times when in Church. A steward will guide you at Communion time and the Priest will place Holy Communion on your hand. You may place your Offertory Thanksgiving in the collection plate which will be available as you leave the church. We need to follow the Government and Diocesan Guidelines on social distancing, so if you know you intend to join us at Mass in either of our churches one weekend, it will be a great help if you let us know so that we can allocate you a place, preferably by e-mail to [email protected], or phone 01424 773125 by 9am on Thursday or earlier in the week if possible, as the office closes at lunchtime on Thursday. -

Friends of Quarr

Quarr Abbey Newsletter Autumn 2017 6/12/17 10:16 Page 1 Quarr Issue 18 Abbey Autumn/Winter N E W S L E T T E R 2017 A Deeper Look Anyone who approaches the Crib of Bethlehem is invited to a deeper look. A simple gaze, or one which is only superficial, cannot see what all this is about – the sheep and the camels, the shepherds and the magi, the couple and the Child, the angels and the star. All these are parts of a well-known scene. They form a picturesque and lovely vision. They Friends of Quarr figure a world at peace, focussed on the Child in the cradle, who seems to be a child like any child, you and me as a child, in the beauty and peace It is a great pleasure to report that The of an ideal time and space. Walled Garden Project was completed on the 8th July 2017 when The Lord Only take a deeper look, though. You might need a moment of silence Lieutenant, Major General White and for this; or the peaceful melody of, say, a Carol, or Gregorian chant. The Mrs White, joined the Friends and the Child, of course, is the centre, and everything revolves around him in a Community of Quarr and guests to movement that no other child, not even an ideal one could generate. All celebrate its completion. The move towards Him who seems the only one fully at rest. When finally Celebration was held in a marquee on the lawn in front of the church.