Diplopoda — Phylogenetic Relationships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supra-Familial Taxon Names of the Diplopoda Table 4A

Milli-PEET, Taxonomy Table 4 Page - 1 - Table 4: Supra-familial taxon names of the Diplopoda Table 4a: List of current supra-familial taxon names in alphabetical order, with their old invalid counterpart and included orders. [Brackets] indicate that the taxon group circumscribed by the old taxon group name is not recognized in Shelley's 2003 classification. Current Name Old Taxon Name Order Brannerioidea in part Trachyzona Verhoeff, 1913 Chordeumatida Callipodida Lysiopetalida Chamberlin, 1943 Callipodida [Cambaloidea+Spirobolida+ Chorizognatha Verhoeff, 1910 Cambaloidea+Spirobolida+ Spirostreptida] Spirostreptida Chelodesmidea Leptodesmidi Brölemann, 1916 Polydesmida Chelodesmidea Sphaeriodesmidea Jeekel, 1971 Polydesmida Chordeumatida Ascospermophora Verhoeff, 1900 Chordeumatida Chordeumatida Craspedosomatida Jeekel, 1971 Chordeumatida Chordeumatidea Craspedsomatoidea Cook, 1895 Chordeumatida Chordeumatoidea Megasacophora Verhoeff, 1929 Chordeumatida Craspedosomatoidea Cheiritophora Verhoeff, 1929 Chordeumatida Diplomaragnoidea Ancestreumatoidea Golovatch, 1977 Chordeumatida Glomerida Plesiocerata Verhoeff, 1910 Glomerida Hasseoidea Orobainosomidi Brolemann, 1935 Chordeumatida Hasseoidea Protopoda Verhoeff, 1929 Chordeumatida Helminthomorpha Proterandria Verhoeff, 1894 all helminthomorph orders Heterochordeumatoidea Oedomopoda Verhoeff, 1929 Chordeumatida Julida Symphyognatha Verhoeff, 1910 Julida Julida Zygocheta Cook, 1895 Julida [Julida+Spirostreptida] Diplocheta Cook, 1895 Julida+Spirostreptida [Julida in part[ Arthrophora Verhoeff, -

Biochemical Divergence Between Cavernicolous and Marine

The position of crustaceans within Arthropoda - Evidence from nine molecular loci and morphology GONZALO GIRIBET', STEFAN RICHTER2, GREGORY D. EDGECOMBE3 & WARD C. WHEELER4 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary- Biology, Museum of Comparative Zoology; Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. ' Friedrich-Schiller-UniversitdtJena, Instituifiir Spezielte Zoologie und Evolutionsbiologie, Jena, Germany 3Australian Museum, Sydney, NSW, Australia Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, U.S.A. ABSTRACT The monophyly of Crustacea, relationships of crustaceans to other arthropods, and internal phylogeny of Crustacea are appraised via parsimony analysis in a total evidence frame work. Data include sequences from three nuclear ribosomal genes, four nuclear coding genes, and two mitochondrial genes, together with 352 characters from external morphol ogy, internal anatomy, development, and mitochondrial gene order. Subjecting the com bined data set to 20 different parameter sets for variable gap and transversion costs, crusta ceans group with hexapods in Tetraconata across nearly all explored parameter space, and are members of a monophyletic Mandibulata across much of the parameter space. Crustacea is non-monophyletic at low indel costs, but monophyly is favored at higher indel costs, at which morphology exerts a greater influence. The most stable higher-level crusta cean groupings are Malacostraca, Branchiopoda, Branchiura + Pentastomida, and an ostracod-cirripede group. For combined data, the Thoracopoda and Maxillopoda concepts are unsupported, and Entomostraca is only retrieved under parameter sets of low congruence. Most of the current disagreement over deep divisions in Arthropoda (e.g., Mandibulata versus Paradoxopoda or Cormogonida versus Chelicerata) can be viewed as uncertainty regarding the position of the root in the arthropod cladogram rather than as fundamental topological disagreement as supported in earlier studies (e.g., Schizoramia versus Mandibulata or Atelocerata versus Tetraconata). -

Gonopod Mechanics in Centrobolus Cook (Spirobolida: Trigoniulidae) II

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2016; 4(2): 152-154 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 JEZS 2016; 4(2): 152-154 Gonopod mechanics in Centrobolus Cook © 2016 JEZS (Spirobolida: Trigoniulidae) II. Images Received: 06-01-2016 Accepted: 08-02-2016 Mark Ian Cooper Mark Ian Cooper A) Department of Biological Sciences, Private Bag X3, Abstract University of Cape Town, Gonopod mechanics were described for four species of millipedes in the genus Centrobolus and are now Rondebosch 7701, South Africa. figured using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with the aim to show the mechanism of sperm B) Electron Microscope Unit & Structural Biology Research competition. Structures of sperm displacement include projections on a moveable telopodite and tips on a Unit, University of Cape Town, distal process (opisthomerite). Three significant contact zones between the male and female genitalia South Africa. were recognized: (1) distal telopodite of the coleopod and the vulva, (2) phallopod and the bursa, (3) sternite and legs of the female. Keywords: coleopods, diplopod, gonopods, phallopods 1. Introduction The dual function of millipede male genitalia in sperm displacement and transfer were predicted from the combined examination of the ultrastructures of the male and female genitalia [1-3]. Genitalic structures function do not only in sperm transfer during the time of copulation, but that they perform copulatory courtship through movements and interactions with the female genitalia [4-5]. These 'functional luxuries' can induce cryptic female choice by stimulating structures on the female genitalia while facilitating rival-sperm displacement and sperm transfer. Genitalic complexity is probably underestimated in many species because they have only been studied in the retracted or relaxed state [4]. -

A New Genus of the Millipede Tribe Brachyiulini (Diplopoda: Julida: Julidae) from the Aegean Region

European Journal of Taxonomy 70: 1-12 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2013.70 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2013 · Lazányi E. & Vagalinski B. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:5E23F454-2A68-42F6-86FB-7D9952B2FE7B A new genus of the millipede tribe Brachyiulini (Diplopoda: Julida: Julidae) from the Aegean region Eszter LAZÁNYI1,4 & Boyan VAGALINSKI2,3,5 1 Corresponding author: Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum, Baross u. 13, H-1088 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Faculty of Biology, Sofia University, 8 Dragan Tsankov Blvd., 1164 Sofia, Bulgaria. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 2 Yurii Gagarin Street, 1113, Sofia, Bulgaria. 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:02DB48F1-624C-4435-AF85-FA87168CD85A 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:973B8725-039E-4F29-8D73-96A7F52CF934 Abstract. A new genus of the julid tribe Brachyiulini, Enghophyllum gen. nov., is described, comprising two species from Greece. The type-species, E. naxium (Verhoeff, 1901) comb. nov. (ex Megaphyllum Verhoeff, 1894), appears to be rather widespread in the Aegean: it is known from Antiparos Island and Naxos Island (the type locality), both in the Cyclades, as well as East Mavri Islet, Dodecanese Archipelago (new record). The vulva of E. naxium is described for the first time. In addition,E. sifnium gen. et sp. nov. is described based on a single adult male from Sifnos Island, Cyclades. The new genus is distinct from other genera of the Brachyiulini mainly by its peculiar gonopod structure, apparently disjunct and at least mostly apomorphous: (1) promeres broad, shield-like, in situ protruding mostly posteriad, completely covering the opisthomeres and gonopodal sinus; (2) transverse muscles and coxal apodemes of promere fully reduced; (3) opisthomere with three differentiated processes, i.e., lateral, basal posterior and apical posterior; (4) solenomere rather simple, tubular. -

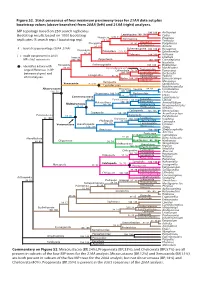

Figure S2. Strict Consensus of Four Maximum Parsimony Trees for 21AA Data Set Plus Bootstrap Values (Above Branches) from 20AA (Left) and 21AA (Right) Analyses

Figure S2. Strict consensus of four maximum parsimony trees for 21AA data set plus bootstrap values (above branches) from 20AA (left) and 21AA (right) analyses. MP topology based on 250 search replicates. 100 100 Antheraea Bootstrap results based on 1000 bootstrap Lepidoptera 100 100 Cydia Neoptera [23] 44 Dermaptera Prodoxus replicates (5 search reps / bootstrap rep). 68 66 Forficula Blattodea Pterygota 92 96 Periplaneta Orthoptera 96 97 Acheta # : bootstrap percentage (20AA 21AA) Ephemeroptera Dicondylia 100 100 Hexagenia Paleoptera [37] 52 Ephemerella 98 98 Odonata 100 100 Ischnura [ ] : node not present in 20AA Insecta Libellula MP strict consensus 100 100 Zygentoma 100 100 Ctenolepisma Nicoletia Archaeognatha : Identifies 6 taxa with Hexapoda 100 100 Pedetontus 89 86 Machiloides Entomobryomorpha Tomoceridae large differences in BP Collembola 70 76 Tomocerus between degen1 and 100 100 Entomobryidae Orchesella Entognatha 82 82 Poduridae Podura 20AA analyses. Diplura 100 100 Campodeidae Japygidae Eumesocampa Remipedia Metajapyx Xenocarida [31] 51 Speleonectes Cephalocarida Hutchinsoniella Altocrustacea Thoracica Sessilia 88 83 Semibalanus [14] 31 100 100 Chthamalus Thecostraca 100 100 Pedunculata Lepas Communostraca Rhizocephala Loxothylacus 96 89 Eumalacostraca 84 85 Eucarida Libinia Malacostraca 100 100 Peracarida Armadillidium Multicrustacea 100 100 Hoplocarida 69 84 Neogonodactylus Phyllocarida Nebalia Cyclopoida 100 100 Mesocyclops Copepoda 100 100 Acanthocyclops Pancrustacea 65 82 Calanoida Eurytemora 96 100 Diplostraca 100 100 -

Exploring Phylogenomic Relationships Within Myriapoda: Should High Matrix Occupancy Be the Goal?

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/030973; this version posted November 9, 2015. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Exploring phylogenomic relationships within Myriapoda: should high matrix occupancy be the goal? ROSA FERNÁNDEZ1, GREGORY D. EDGECOMBE2 AND GONZALO GIRIBET1 1Museum of Comparative Zoology & Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 2Department of Earth Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/030973; this version posted November 9, 2015. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract.—Myriapods are one of the dominant terrestrial arthropod groups including the diverse and familiar centipedes and millipedes. Although molecular evidence has shown that Myriapoda is monophyletic, its internal phylogeny remains contentious and understudied, especially when compared to those of Chelicerata and Hexapoda. Until now, efforts have focused on taxon sampling (e.g., by including a handful of genes in many species) or on maximizing matrix occupancy (e.g., by including hundreds or thousands of genes in just a few species), but a phylogeny maximizing sampling at both levels remains elusive. In this study, we analyzed forty Illumina transcriptomes representing three myriapod classes (Diplopoda, Chilopoda and Symphyla); twenty-five transcriptomes were newly sequenced to maximize representation at the ordinal level in Diplopoda and at the family level in Chilopoda. -

Annexure I Fauna & Flora Assessment.Pdf

Fauna and Flora Baseline Study for the De Wittekrans Project Mpumalanga, South Africa Prepared for GCS (Pty) Ltd. By Resource Management Services (REMS) P.O. Box 2228, Highlands North, 2037, South Africa [email protected] www.remans.co.za December 2008 I REMS December 2008 Fauna and Flora Assessment De Wittekrans Executive Summary Mashala Resources (Pty) Ltd is planning to develop a coal mine south of the town of Hendrina in the Mpumalanga province on a series of farms collectively known as the De Wittekrans project. In compliance with current legislation, they have embarked on the process to acquire environmental authorisation from the relevant authorities for their proposed mining activities. GCS (Pty) Ltd. commissioned Resource Management Services (REMS) to conduct a Faunal and Floral Assessment of the area to identify the potential direct and indirect impacts of future mining, to recommend management measures to minimise or prevent these impacts on these ecosystems and to highlight potential areas of conservation importance. This is the wet season survey which was done in the November 2008. The study area is located within the highveld grasslands of the Msukaligwa Local Municipality in the Gert Sibande District Municipality in Mpumalanga Province on the farms Tweefontein 203 IS (RE of Portion 1); De Wittekrans 218 IS (RE of Portion 1 and Portion 2, Portions 7, 11, 10 and 5); Groblershoek 191 IS; Groblershoop 192 IS; and Israel 207 IS. Within this region, precipitation occurs mainly in the summer months of October to March with the peak of the rainy season occurring from November to January. -

A New Species of Illacme Cook & Loomis, 1928

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 626: 1–43A new (2016) species of Illacme Cook and Loomis, 1928 from Sequoia National Park... 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.626.9681 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A new species of Illacme Cook & Loomis, 1928 from Sequoia National Park, California, with a world catalog of the Siphonorhinidae (Diplopoda, Siphonophorida) Paul E. Marek1, Jean K. Krejca2, William A. Shear3 1 Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Department of Entomology, Price Hall, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA 2 Zara Environmental LLC, 1707 W FM 1626, Manchaca, Texas, USA 3 Hampden-Sydney College, Department of Biology, Gilmer Hall, Hampden-Sydney, Virginia, USA Corresponding author: Paul E. Marek ([email protected]) Academic editor: R. Mesibov | Received 25 July 2016 | Accepted 19 September 2016 | Published 20 October 2016 http://zoobank.org/36E16503-BC2B-4D92-982E-FC2088094C93 Citation: Marek PE, Krejca JK, Shear WA (2016) A new species of Illacme Cook & Loomis, 1928 from Sequoia National Park, California, with a world catalog of the Siphonorhinidae (Diplopoda, Siphonophorida). ZooKeys 626: 1–43. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.626.9681 Abstract Members of the family Siphonorhinidae Cook, 1895 are thread-like eyeless millipedes that possess an astounding number of legs, including one individual with 750. Due to their cryptic lifestyle, rarity in natural history collections, and sporadic study over the last century, the family has an unclear phylogenetic placement, and intrafamilial relationships remain unknown. Here we report the discovery of a second spe- cies of Illacme, a millipede genus notable for possessing the greatest number of legs of any known animal on the planet. -

Order CALLIPODIDA Manual Versión Española

Revista IDE@ - SEA, nº 25B (30-06-2015): 1–12. ISSN 2386-7183 1 Ibero Diversidad Entomológica @ccesible www.sea-entomologia.org/IDE@ Class: Diplopoda Order CALLIPODIDA Manual Versión española CLASS DIPLOPODA Order Callipodida Jörg Spelda Bavarian State Collection of Zoology Münchhausenstraße 21, 81247 Munich, Germany [email protected] 1. Brief characterization of the group and main diagnostic characters 1.1. Morphology The members of the order Callipodida are best recognized by their putative apomorphies: a divided hypoproct, divided anal valves, long extrusible tubular vulvae, and, as in all other helminthomorph milli- pede orders, a characteristic conformation of the male gonopods. As in Polydesmida, only the first leg pair of the 7th body ring is transformed into gonopods, which are retracted inside the body. Body rings are open ventrally and are not fused with the sternites, leaving the coxae of the legs free. Legs in the anterior half of the body carry coxal pouches. The small collum does not overlap the head. Callipodida are of uniformly cylindrical external appearance. The number of body rings is only sometimes fixed in species and usually exceeds 40. There are nine antennomeres, as the 2nd antennomere of other Diplopoda is subdivided (= antennomere 2 and 3 in Callipodida). The general struc- ture of the gnathochilarium is shared with the Chordeumatida and Polydesmida. Callipodida are said to be characterised by longitudinal crests, which gives the order the common name “crested millipedes”. Although crest are present in most species, some genera (e.g. Schizopetalum) lack a crest, while some Spirostreptida ( e.g. in Cambalopsidae, ‘Trachystreptini’) and some Julida (e.g. -

The Millipedes and Centipedes of Chiapas Amber

14 4 ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES Check List 14 (4): 637–646 https://doi.org/10.15560/14.4.637 The millipedes and centipedes of Chiapas amber Francisco Riquelme1, Miguel Hernández-Patricio2 1 Laboratorio de Sistemática Molecular. Escuela de Estudios Superiores del Jicarero, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Jicarero C.P. 62909, Morelos, Mexico. 2 Subcoordinación de Inventarios Bióticos, Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Tlalpan C.P. 14010, Mexico City, Mexico. Corresponding author: Francisco Riquelme, [email protected] Abstract An inventory of fossil millipedes (class Diplopoda) and centipedes (class Chilopoda) from Miocene Chiapas amber, Mexico, is presented, with the inclusion of new records. For Diplopoda, 34 members are enumerated, for which 31 are described as new fossil records of the orders Siphonophorida Newport, 1844, Spirobolida Bollman, 1893, Polydesmida Leach, 1895, Stemmiulida Pocock, 1894, and the superorder Juliformia Attems, 1926. For Chilopoda 8 fossils are listed, for which 3 are new records of the order Geophilomorpha Pocock, 1895 and 2 are of the order Scolopendromorpha Pocock, 1895. Key words Miocene, Mexico, Diplopoda, Chilopoda. Academic editor: Peter Dekker | Received 14 May 2018 | Accepted 26 July 2018 | Published 10 August 2018 Citation: Riquelme F, Hernández-Patricio F (2018) The millipedes and centipedes of Chiapas amber. Check List 14 (4): 637–646. https://doi. org/10.15560/14.4.637 Introduction Diplopoda fossil record worldwide (Edgecombe 2015). Two other centipedes have been reported in Ross et al. The extant species of millipedes and centipedes distributed (2016). Other records of millipedes have been mentioned across Mexico have been studied since the initial reports in the literature but are questionable because of a lack of Brand (1839) and Persbosc (1839). -

Ordinal-Level Phylogenomics of the Arthropod Class

Ordinal-Level Phylogenomics of the Arthropod Class Diplopoda (Millipedes) Based on an Analysis of 221 Nuclear Protein-Coding Loci Generated Using Next- Generation Sequence Analyses Michael S. Brewer1,2*, Jason E. Bond3 1 Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California, United States of America, 2 Department of Biology, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, United States of America, 3 Department of Biological Sciences and Auburn University Museum of Natural History, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, United States of America Abstract Background: The ancient and diverse, yet understudied arthropod class Diplopoda, the millipedes, has a muddled taxonomic history. Despite having a cosmopolitan distribution and a number of unique and interesting characteristics, the group has received relatively little attention; interest in millipede systematics is low compared to taxa of comparable diversity. The existing classification of the group comprises 16 orders. Past attempts to reconstruct millipede phylogenies have suffered from a paucity of characters and included too few taxa to confidently resolve relationships and make formal nomenclatural changes. Herein, we reconstruct an ordinal-level phylogeny for the class Diplopoda using the largest character set ever assembled for the group. Methods: Transcriptomic sequences were obtained from exemplar taxa representing much of the diversity of millipede orders using second-generation (i.e., next-generation or high-throughput) sequencing. These data were subject to rigorous orthology selection and phylogenetic dataset optimization and then used to reconstruct phylogenies employing Bayesian inference and maximum likelihood optimality criteria. Ancestral reconstructions of sperm transfer appendage development (gonopods), presence of lateral defense secretion pores (ozopores), and presence of spinnerets were considered. -

Diplopoda, Sphaerotheriida, Arthrosphaeridae)

European Journal of Taxonomy 758: 1–48 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2021.758.1423 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2021 · Wesener T. & Sagorny C. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:01BBC12C-E715-4393-A9F6-6EA85CB1289F Seven new giant pill-millipede species and numerous new records of the genus Zoosphaerium from Madagascar (Diplopoda, Sphaerotheriida, Arthrosphaeridae) Thomas WESENER 1,* & Christina SAGORNY 2 1,2 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig (ZFMK), Leibniz Institute for Animal Biodiversity, Section Myriapoda, Adenauerallee 160, D-53113 Bonn, Germany. 2 University of Bonn, Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Ecology, D-53121 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:86DEA7CD-988C-43EC-B9D6-C51000595B47 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:9C89C1B7-897A-426E-8FD4-C747DF004C85 Abstract. Seven new species of the giant pill-millipede genus Zoosphaerium Pocock, 1895 are described from Madagascar: Z. nigrum sp. nov., Z. silens sp. nov., Z. ambatovaky sp. nov., Z. beanka sp. nov., Z. voahangy sp. nov., Z. masoala sp. nov. and Z. spinopiligerum sp. nov. All species are described based on drawings and scanning electron microscopy, while genetic barcoding of the COI gene was successful for six of the seven new species. Additional COI barcode information is provided for the fi rst time for Z. album Wesener, 2009 and Z. libidinosum (de Saussure & Zehntner, 1897). Zoosphaerium nigrum sp. nov. and Z. silens sp. nov. belong to the Z. libidinosum species-group, Z.