Handicapping Currency Design: Counterfeit Deterrence and Visual Accessibility in the United States and Abroad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report – Made in PRD: the Changing Face of HK Manufacturers – Released in 2003

MADE IN Challenges & Opportunities for HK Industry Made in PRD Study is a Federation of Hong Kong Industries project. The Hong Kong Centre for Economic Research was commissioned to carry out this two-year Study. Published and printed in Hong Kong. HK$500 Published by Federation of Hong Kong Industries. Copyright © 2007 Federation of Hong Kong Industries. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the Federation of Hong Kong Industries. Website : http://www.industryhk.org Contents 2 Foreword 8 Chapter 1 : Hong Kong and the Pearl and Yangtze River Deltas 28 Chapter 2 : Industrial Performance in Gunagdong and the Role of Hong Kong 42 Chapter 3 : Hong Kong-Funded Enterprises and Enterprises in Other Contractual Forms 56 Chapter 4 : The Characteristics of Product Sales 66 Chapter 5 : Guangdong and Hong Kong in Parternership 80 Chapter 6 : Business Environment of the PRD 94 Chapter 7 : Research & Development 110 Chapter 8 : Policy Recommendations 126 Glossary 128 Acknowledgements 1 Since China embarked on the historic economic reform Foreword programmes in late 1970s, the Pearl River Delta (PRD) has developed by leaps and bounds from a predominately rural region into one of the fastest growing, export- oriented industrial centres in the world. This spectacular transformation and the contributions that Hong Kong manufacturers had made to the process have been lucidly depicted in our study report – Made in PRD: The Changing Face of HK Manufacturers – released in 2003. -

Annual Report 2014 • Hong Kong Monetary Authority Page 5

2014 Annual Report Page 2 Hong Kong Monetary Authority The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) is the government authority in Hong Kong responsible for maintaining monetary and banking stability. The HKMA’s policy objectives are • to maintain currency stability within the framework of the Linked Exchange Rate system • to promote the stability and integrity of the financial system, including the banking system • to help maintain Hong Kong’s status as an international financial centre, including the maintenance and development of Hong Kong’s financial infrastructure • to manage the Exchange Fund. The HKMA is an integral part of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government but operates with a high degree of autonomy, complemented by a high degree of accountability and transparency. The HKMA is accountable to the people of Hong Kong through the Financial Secretary and through the laws passed by the Legislative Council that set out the Monetary Authority’s powers and responsibilities. In his control of the Exchange Fund, the Financial Secretary is advised by the Exchange Fund Advisory Committee. The HKMA’s offices are at 55/F, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong Telephone : (852) 2878 8196 Facsimile : (852) 2878 8197 E-mail : [email protected] The HKMA Information Centre is located at 55/F, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong and is open from 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Monday to Friday and 10:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. on Saturday (except public holidays). The Centre consists of an Exhibition Area and a Library containing materials on Hong Kong’s monetary, banking and financial affairs and central banking topics. -

Video on Showcase of Awarded Websites and Mobile Applications

Video on Showcase of Awarded Websites and Mobile Applications Most Favourite Websites 1. The Kowloon Motor Bus Company (1933) Limited [www.kmb.hk] 2. The University of Hong Kong [www.hku.hk] 3. The Chinese University of Hong Kong [www.cuhk.edu.hk] Most Favourite Mobile App 4. MTR Corporation Limited [MTR Mobile , iOS / Android] 5. Airport Authority Hong Kong [HKG My Flight , iOS / Android] 6. Hong Kong Blind Union [Searching & Exploring with Speech Augmented Map Information (SESAMI) , iOS] Designer Award 1. TheOrigo Ltd. 2. Palmary Solutions Company Limited 3. KanHan Technologies Limited Triple Gold Award 1. Arcotect Limited [www.arcotect.com] 2. Automated Systems Holdings Limited [www.asl.com.hk] 3. The Chinese University of Hong Kong [www.cuhk.edu.hk] 4. City University of Hong Kong [www.cityu.edu.hk/cityu] 5. City University of Hong Kong [www.cityu.edu.hk/cio] 6. Fish Marketing Organization [www.fmo.org.hk] 7. Freedom Communications Limited [www.freecomm.com/entxt_index.php] 8. The Hong Kong Council of Social Service [dsf.org.hk] 9. HKCSS - HSBC Social Enterprise Business Centre [www.sobiz.hk] 10. Information Technology Resource Centre Limited [itrc.hkcss.org.hk] 11. Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health [www.smokefree.hk] 12. Hong Kong Cyberport Management Company Limited [www.cyberport.hk] 13. Hong Kong Institute of Vocational Education [it.vtc.edu.hk] 14. Hong Kong Lutheran Social, LC-HKS - Shek Kip Mei Lutheran Centre for the Blind [smartlink.hklcb.org/index2.php] 15. Hong Kong Note Printing Limited [www.hknpl.com.hk] 16. Health, Safety and Environment Office, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University [www.polyu.edu.hk/hseo] 17. -

Graduates Subsidy Programme 2021

Guidance Notes on Application for Green Employment Scheme: Graduates Subsidy Programme 2021 Preamble The purpose of Green Employment Scheme: Graduates Subsidy Programme 2021 (the Programme) is to provide subsidies to prospective employers of graduates of environment- related disciplines with a view to sustaining the provision of job opportunities for fresh graduates to work in environment-related areas as well as nurturing young people with environmental knowledge, talents and passion to meet the environmental needs of Hong Kong. Responsible Government Department 2. Environmental Protection Department (EPD) is responsible for the implementation of the Programme. Eligibility for the Programme 3. An applicant must be a holder of a valid business registration certificate and (a) has recently recruited an Eligible Graduate employee (see para.5 below) who reported duty on or after 1 April 2021; or (b) is in the process of recruiting; or (c) is planning to recruit at least one Eligible Graduate employee, to work on a full-time basis in an Eligible Job Place (see para.6 below). 4. An applicant without a valid business registration certificate and under the following circumstances will also be considered on a case-by-case basis: (a) Applicant registered in Company Registry with valid Company Registration Certificate; or (b) Applicant being a charitable institution under Section 88 of the Inland Revenue Ordinance; or (c) Applicant being an organization registered under the Societies Ordinance (Cap. 151). 5. An Eligible Graduate employee under the Programme must be: (a) a fresh graduate who has completed a Bachelor’s degree programme in a relevant environment-related subjectNote 1 from a Hong Kong higher education institution, or equivalent, in 2020 or 2021; (b) a Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) resident with a valid Hong Kong Identity Card; and Note 1 Environmental conservation, environmental science, environmental management, sustainable development or other subjects relevant to the duties of the Eligible Job Places. -

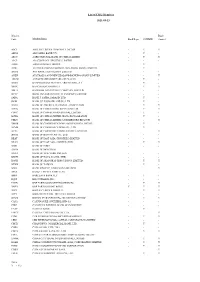

List of CMU Members 2021-08-18

List of CMU Members 2021-09-23 Member Bond Code Member Name Bank Repo CMUBID Connect ABCI ABCI SECURITIES COMPANY LIMITED - Y Y ABNA ABN AMRO BANK N.V. - Y - ABOC AGRICULTURAL BANK OF CHINA LIMITED - Y Y AIAT AIA COMPANY (TRUSTEE) LIMITED - - - ASBK AIRSTAR BANK LIMITED - Y - ACRL ALLIED BANKING CORPORATION (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y - ANTB ANT BANK (HONG KONG) LIMITED - - - ANZH AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BANKING GROUP LIMITED - - Y AMCM AUTORIDADE MONETARIA DE MACAU - Y - BEXH BANCO BILBAO VIZCAYA ARGENTARIA, S.A. - Y - BSHK BANCO SANTANDER S.A. - Y Y BBLH BANGKOK BANK PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED - - - BCTC BANK CONSORTIUM TRUST COMPANY LIMITED - - - SARA BANK J. SAFRA SARASIN LTD - Y - JBHK BANK JULIUS BAER AND CO. LTD. - Y - BAHK BANK OF AMERICA, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION - Y Y BCHK BANK OF CHINA (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y Y CDFC BANK OF CHINA INTERNATIONAL LIMITED - Y - BCHB BANK OF CHINA LIMITED, HONG KONG BRANCH - Y - CHLU BANK OF CHINA LIMITED, LUXEMBOURG BRANCH - - Y BMHK BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y - BCMK BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS CO., LTD. - Y - BCTL BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS TRUSTEE LIMITED - - Y DGCB BANK OF DONGGUAN CO., LTD. - - - BEAT BANK OF EAST ASIA (TRUSTEES) LIMITED - - - BEAH BANK OF EAST ASIA, LIMITED (THE) - Y Y BOIH BANK OF INDIA - - - BOFM BANK OF MONTREAL - - - BNYH BANK OF NEW YORK MELLON - - - BNSH BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA (THE) - - - BOSH BANK OF SHANGHAI (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y Y BTWH BANK OF TAIWAN - Y - SINO BANK SINOPAC, HONG KONG BRANCH - - Y BPSA BANQUE PICTET AND CIE SA - - - BBID BARCLAYS BANK PLC - Y - EQUI BDO UNIBANK, INC. -

Growing with Stronger Foundations

BOC Hong Kong (Holdings) Limited Summary Financial Report 2003 Growing with Stronger Foundations This Summary Financial Report only gives a summary of the information and particulars contained in the “2003 Annual Report” (“annual report”) of the Company from which this Summary Financial Report is derived. Both the annual report and this Summary Financial Report are available (in both English and Chinese) on the Company’s website at www.bochkholdings.com. You may obtain, free of charge, 52/F Bank of China Tower, 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong a copy of the annual report (English or Chinese or both) from the Website: www.bochkholdings.com Company’s Share Registrar, Computershare Hong Kong Investor Services Limited, details of which are set out in Shareholder Information of this Summary Financial Report. Summary Financial Report 2003 Contents BOC Hong Kong (Holdings) Limited (“the Company”) was incorporated in Hong Kong 1 Financial Highlights on September 12, 2001 to hold the entire equity interest in Bank of China (Hong Kong) 2 Five-Year Financial Summary Limited (“BOCHK”), its principal operating 5 Chairman’s Statement subsidiary. Bank of China holds a substantial part of its interests in the shares of the 7 Chief Executive’s Report Company through BOC Hong Kong (BVI) Limited, an indirect wholly owned subsidiary 13 Management’s Discussion of Bank of China. and Analysis BOCHK is a leading commercial banking group in Hong Kong. With approximately 300 37 Corporate Information branches and about 450 ATMs and other 39 Board of Directors and delivery channels in Hong Kong, it offers a comprehensive range of financial products Senior Management and services to retail and corporate customers. -

MONEY in HONG KONG Money in Hong Kong

HONG KONG MONETARY AUTHORITY 55th Floor, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong Telephone: (852) 2878 8196 Facsimile: (852) 2878 8197 E-mail: [email protected] www.hkma.gov.hk MONEY IN HONG KONG Money in Hong Kong Hong Kong’s currency notes are issued by three commercial banks, except for the $10 notes which are issued by the Hong Kong SAR Government. Coins are also issued by the Government. All Hong Kong’s notes and coins are fully backed by US dollar reserves held in the Exchange Fund. Notes in Hong Kong Notes in everyday circulation in Hong Kong are in $10, $20, $50, $100, $500 and $1,000 denominations. The Government, through the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, has authorised three commercial banks, The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited, the Standard Chartered Bank (Hong Kong) Limited, and the Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited, to issue notes in Hong Kong other than the $10 notes. The Government began issuing a paper $10 note in 2002 to meet continuing demand from the public for a note in addition to the $10 coin. In 2007, the Government issued a polymer $10 note alongside the paper one. The $10 notes issued by two note-issuing banks in the 1990s remain legal tender, but are no longer printed. Coins in Hong Kong The Government issues $10, $5, $2, $1, 50-cent, 20-cent and 10- cent coins. There are two series of coins in circulation: the bauhinia series and the Queen’s Head series. The bauhinia series was introduced in 1993 to gradually replace the Queen’s Head series. -

Hong Kong ICAC Medal for Distinguished Service, the Hong Kong ICAC Medal for Meritorious Service and the Chief Executive's Commendation for Government/Public Service

香港特別行政區廉政公署 Independent Commission Against Corruption Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 二零一九年年報 2019 Annual Report 遵照香港特別行政區法例第204章廉政公署條例第17條,呈 交 行 政 長 官。 Submitted to the Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region in accordance with section 17 of the Independent Commission Against Corruption Ordinance (Cap 204). 廉政公署 使命宣言及專業守則 INDEPENDENT COMMISSION AGAINST CORRUPTION MISSION STATEMENT AND CODE OF ETHICS 廉政公署致力維護本港公平正義,安定 With the community, the ICAC is committed to 繁榮,務必與全體市民齊心協力,堅定不 fighting corruption through effective law enforcement, 移,以執法、教育、預防三管齊下,肅貪 education and prevention to help keep Hong Kong fair, 倡 廉。 just, stable and prosperous. 廉署人員無論何時都致力維護本署的良 Officers of the ICAC will at all times uphold the good 好 聲 譽,並 嚴 格 遵 守 以 下 的 專 業 守 則: name of the Commission and ◾ 堅守誠信和公平的原則; ◾ adhere to the principles of integrity and fair play; ◾ 尊 重 任 何 人 的 合 法 權 利; ◾ respect the rights under the law of all people; ◾ 不 懼 不 偏,大 公 無 私 執 行 職 務; ◾ carry out their duties without fear or favour, prejudice or ill will; ◾ 絕 對 依 法 行 事; ◾ act always in accordance with the law; ◾ 不以權位謀私; ◾ not take advantage of their authority or position; ◾ 根據實際需要嚴守保密原則; ◾ maintain necessary confidentiality; ◾ 為自己的行為及所作的指示承擔責任; ◾ accept responsibility for their actions and ◾ 言 行 抑 制 而 有 禮; instructions; ◾ 在 個 人 及專 業修 養 上 力求至善。 ◾ exercise courtesy and restraint in word and action; ◾ strive for personal and professional excellence. 1 目錄 CONTENTS 第一章 CHAPTER 01 4 第三章 CHAPTER 03 20 緒言 行政總部 1 INTRODUCTION 3 ADMINISTRATION BRANCH 體制 Constitution 5 -

Localizing Public Dispute Resolution in Japan: Lessons from Experiments with Deliberative Policy-Making By

Localizing Public Dispute Resolution in Japan: Lessons from experiments with deliberative policy-making by Masahiro Matsuura Master in City Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1998 B. Eng. Civil Engineering University of Tokyo, 1996 Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban and Regional Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2006 © 2006 Masahiro Matsuura. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of author: Dep artment of Urban Studies and Planning June 27, 2006 Certified by: Lawrence E. Susskind Ford Professor of Urban and Environmental Planning, Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Frank Levy, Daniel Rose Professor of Urban Economics, Chair, Ph.D. Committee 2 Localizing Public Dispute Resolution in Japan: Lessons from experiments with deliberative policy-making by Masahiro Matsuura Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on August 11, 2006 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban and Regional Planning ABSTRACT Can consensus building processes, as practiced in the US, be used to resolve infrastructure disputes in Japan? Since the 1990s, proposals to construct highways, dams, ports and airports, railways, as well as to redevelop neighborhoods, have been opposed by a wide range of stakeholders. In response, there is a growing interest among Japanese practitioners in using consensus building processes, as practiced in the US, in order to resolve infrastructure disputes. -

List of Energywi$E Certificate Awardees 獲得節能證書的參與單位名單

List of Energywi$e Certificate Awardees 獲得節能證書的參與單位名單 Energywi$e Expiry Date Basic Level Good Level Excellence Level No. Company Name and Name of Venue/Office/Premises 公司名稱 / 地點 / 辦公室 / 處所 Membership No. 屆滿日期 基礎級別 良好級別 卓越級別 1 EW-3429-5020 TOPPAN FORMS CARD TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED 凸版資訊卡片有限公司 3/31/2023 * Chun Wo Construction and Engineering Company Limited - 俊和建築工程有限公司 - Construction of Public Housing Development at Hiu Ming Street 曉明街公營房屋發展計劃的建築工程(重置康樂設施、工地 2 EW-5213-5000 3/31/2023 * (Combined Recreational Facilities Reprovision, Site Formation, 平整工程、地基工程及建築工程的合併合約)-(合約編號 Foundation and Building Contract) – (Contract No.: 20170567) 20170567) Able Engineering Company Limited - Construction of Public Housing 安保工程有限公司 - 3 EW-5213-5008 3/31/2023 * Development at Tuen Mun Area 54 Site 1 &1A 新界屯門第54區1及1A號公營房屋發展計劃 CRCC-Paul Y. Joint Venture - Contract No.: ND/2019/05 - Fanling 中國鐵建15局-保華聯營公司 - North New Development Area, 4 EW-5213-5011 合約編號:ND/2019/05粉嶺北新發展區第一階段- 3/31/2023 * Phase 1: Fanling Bypass Eastern Section (Shung Him Tong to Kau 粉嶺繞道東段(崇謙堂至九龍坑) Lung Hang) 5 EW-8314-5002 Sources Fame Management Ltd. - One Hennessy 源發管理有限公司 3/31/2023 * 6 EW-8314-5006 Together Management Co., Ltd - Jade Grove 合眾物業管理有限公司 - 琨崙 3/31/2023 * 7 EW-8339-5026 WYND Limited - WYND -- 3/31/2023 * Tung Wah Group of Hospitals - Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Lions 8 EW-9314-5016 東華三院 - 東華三院南九龍獅子會幼兒園 3/31/2023 * Club of South Kowloon Nursery School 9 EW-8122-0414 NWS Holdings Limited - The Corporate Office 新創建集團有限公司 - 總寫字樓 3/31/2023 * 10 EW-8315-0163 Centaline Property Agency Limited - Head Office 中原地產代理有限公司 - 總辦事處 3/31/2023 * 11 EW-8339-1714 RHL International Ltd. -

Evaluation of Incorporated Administrative Agencies

EvaluationEvaluation ofof IncorporatedIncorporated AdministrativeAdministrative AgenciesAgencies <Tentative Translation> 2007.6 Administrative Evaluation Bureau Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication Government of Japan 1.1. IncorporatedIncorporated AdministrativeAdministrative AgencyAgency SystemSystem inin JapanJapan 2.2. EvaluationEvaluation ofof IncorporatedIncorporated AdministrativeAdministrative AgenciesAgencies #1#1 - system and the past major achievement - 3.3. EvaluationEvaluation ofof IncorporatedIncorporated AdministrativeAdministrative AgenciesAgencies #2#2 - recent achievement - 4.4. OtherOther TopicsTopics 1.1. IncorporatedIncorporated AdministrativeAdministrative AgencyAgency SystemSystem inin JapanJapan WhatWhat areare IAAsIAAs?? An Incorporated Administrative Agency (IAA) is an organization responsible for indispensable public services Government does not have to do by itself but the private sector is likely to neglect for various reasons. The IAA system was introduced in 2001 as a part of central government reform based on the idea that the planning sectors and the implementing sectors should be separated. [Public sector] [Private sector] Government Private Headquarter and IAAs branch offices companies, etc. of the Ministry BackgroundBackground ofof introducingintroducing thethe IAAIAA systemsystem Problems of the public corporation system Unclearness of management responsibility Inefficiency and opaqueness of business operation Self-propagation of services and internal organi- zations Lack of autonomy concerning -

The Exchange Fund Advisory Committee

2013 Annual Report Hong Kong Monetary Authority The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) is the government authority in Hong Kong responsible for maintaining monetary and banking stability. The HKMA’s policy objectives are • to maintain currency stability within the framework of the Linked Exchange Rate system • to promote the stability and integrity of the financial system, including the banking system • to help maintain Hong Kong’s status as an international financial centre, including the maintenance and development of Hong Kong’s financial infrastructure • to manage the Exchange Fund. The HKMA is an integral part of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government but operates with a high degree of autonomy, complemented by a high degree of accountability and transparency. The HKMA is accountable to the people of Hong Kong through the Financial Secretary and through the laws passed by the Legislative Council that set out the Monetary Authority’s powers and responsibilities. In his control of the Exchange Fund, the Financial Secretary is advised by the Exchange Fund Advisory Committee. The HKMA’s offices are at 55/F, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong Telephone : (852) 2878 8196 Facsimile : (852) 2878 8197 E-mail : [email protected] The HKMA Information Centre is located at 55/F, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong and is open from 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Monday to Friday and 10:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. on Saturday (except public holidays). The Centre consists of an Exhibition Area and a Library containing materials on Hong Kong’s monetary, banking and financial affairs and central banking topics.