Managing Uncertainty: Lessons from Xenophon's Retreat David R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes II John Shannahan BAncHist (Hons) (Macquarie University) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University. May, 2015. ii Contents List of Illustrations v Abstract ix Declaration xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Conventions xv Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY REIGN OF ARTAXERXES II The Birth of Artaxerxes to Cyrus’ Challenge 15 The Revolt of Cyrus 41 Observations on the Egyptians at Cunaxa 53 Royal Tactics at Cunaxa 61 The Repercussions of the Revolt 78 CHAPTER 2 399-390: COMBATING THE GREEKS Responses to Thibron, Dercylidas, and Agesilaus 87 The Role of Athens and the Persian Fleet 116 Evagoras the Opportunist and Carian Commanders 135 Artaxerxes’ First Invasion of Egypt: 392/1-390/89? 144 CHAPTER 3 389-380: THE KING’S PEACE AND CYPRUS The King’s Peace (387/6): Purpose and Influence 161 The Chronology of the 380s 172 CHAPTER 4 NUMISMATIC EXPRESSIONS OF SOLIDARITY Coinage in the Reign of Artaxerxes 197 The Baal/Figure in the Winged Disc Staters of Tiribazus 202 Catalogue 203 Date 212 Interpretation 214 Significance 223 Numismatic Iconography and Egyptian Independence 225 Four Comments on Achaemenid Motifs in 227 Philistian Coins iii The Figure in the Winged Disc in Samaria 232 The Pertinence of the Political Situation 241 CHAPTER 5 379-370: EGYPT Planning for the Second Invasion of Egypt 245 Pharnabazus’ Invasion of Egypt and Aftermath 259 CHAPTER 6 THE END OF THE REIGN Destabilisation in the West 267 The Nature of the Evidence 267 Summary of Current Analyses 268 Reconciliation 269 Court Intrigue and the End of Artaxerxes’ Reign 295 Conclusion: Artaxerxes the Diplomat 301 Bibliography 309 Dies 333 Issus 333 Mallus 335 Soli 337 Tarsus 338 Unknown 339 Figures 341 iv List of Illustrations MAP Map 1 Map of the Persian Empire xviii-xix Brosius, The Persians, 54-55 DIES Issus O1 Künker 174 (2010) 403 333 O2 Lanz 125 (2005) 426 333 O3 CNG 200 (2008) 63 333 O4 Künker 143 (2008) 233 333 R1 Babelon, Traité 2, pl. -

Anton Powell, Nicolas Richer (Eds.), Xenophon and Sparta, the Classical Press of Wales, Swansea 2020, 378 Pp.; ISBN 978-1-910589-74-8

ELECTRUM * Vol. 27 (2020): 213–216 doi:10.4467/20800909EL.20.011.12801 www.ejournals.eu/electrum Anton Powell, Nicolas Richer (eds.), Xenophon and Sparta, The Classical Press of Wales, Swansea 2020, 378 pp.; ISBN 978-1-910589-74-8 The reviewed book is a collection of twelve papers, previously presented at the confe- rence organised by École Normale Supérieure in Lyon in 2006. According to the edi- tors, this is a first volume in the planned series dealing with sources of Spartan his- tory. The books that follow this will deal with the presence of this topic in works by Thucydides, Herodotus, Plutarch, and in archaeological material. The decision to start the cycle from Xenophon cannot be considered as surprising; this ancient author has not only written about Sparta, but also had opportunities to visit the country, person- ally met a number of its officials (including king Agesilaus), and even sent his own sons for a Spartan upbringing. Thus his writings are widely considered as our best source to the history of Sparta in the classical age. Despite this, Xenophon’s literary work remains the subject of numerous controver- sies in discussions among modern scholars. The question of his objectivity is especial- ly problematic and the views about the strong partisanship of Xenophon prevailed for a long time; allegedly, he was depicting Sparta and king Agesilaus in a possibly overly positive light, even omitting inconvenient information.1 In the second half of the 20th century such opinion has been met with a convincing polemic, clearly seen in the works of H. -

Mercenaries, Poleis, and Empires in the Fourth Century Bce

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts ALL THE KING’S GREEKS: MERCENARIES, POLEIS, AND EMPIRES IN THE FOURTH CENTURY BCE A Dissertation in History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies by Jeffrey Rop © 2013 Jeffrey Rop Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 ii The dissertation of Jeffrey Rop was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark Munn Professor of Ancient Greek History and Greek Archaeology, Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Gary N. Knoppers Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, Religious Studies, and Jewish Studies Garrett G. Fagan Professor of Ancient History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Kenneth Hirth Professor of Anthropology Carol Reardon George Winfree Professor of American History David Atwill Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Graduate Program Director for the Department of History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Greek mercenary service in the Near East from 401- 330 BCE. Traditionally, the employment of Greek soldiers by the Persian Achaemenid Empire and the Kingdom of Egypt during this period has been understood to indicate the military weakness of these polities and the superiority of Greek hoplites over their Near Eastern counterparts. I demonstrate that the purported superiority of Greek heavy infantry has been exaggerated by Greco-Roman authors. Furthermore, close examination of Greek mercenary service reveals that the recruitment of Greek soldiers was not the purpose of Achaemenid foreign policy in Greece and the Aegean, but was instead an indication of the political subordination of prominent Greek citizens and poleis, conducted through the social institution of xenia, to Persian satraps and kings. -

The Court of Cyrus the Younger in Anatolia: Some Remarks

STUDIES IN ANCIENT ART AND CIVILIZATION, VOL. 23 (2019) pp. 95-111, https://doi.org/10.12797/SAAC.23.2019.23.05 Michał Podrazik University of Rzeszów THE COURT OF CYRUS THE YOUNGER IN ANATOLIA: SOME REMARKS Abstract: Cyrus the Younger (born in 424/423 BC, died in 401 BC), son of the Great King Darius II (424/423-404 BC) and Queen Parysatis, is well known from his activity in Anatolia. In 408 BC he took power there as a karanos (Old Persian *kārana-, Greek κάρανος), a governor of high rank with extensive military and political competence reporting directly to the Great King. Holding his power in Anatolia, Cyrus had his own court there, in many respects modeled after the Great King’s court. The aim of this article is to show some aspects of functioning and organization of Cyrus the Younger’s court in Anatolia. Keywords: Cyrus the Younger; court; court’s staff and protocol In 4081, Cyrus, commonly known as the Younger (424/423-401), son of the Great King Darius II (424/423-404), was appointed by his father to rule over an important part of the Achaemenid Empire, Anatolia. Cyrus wielded his power there as karanos (Old Persian *kārana-, Greek κάρανος), a high- ranking governor with extensive military and political competence, reporting directly to the Great King (see Podrazik 2018, 69-83; cf. Barkworth 1993, 150-151; Debord 1999, 122-123; Briant 2002, 19, 321, 340, 600, 625-626, 878, 1002; Hyland 2013, 2-5). Cyrus held his own court while in Anatolia. The court was organized along the lines of the King’s court, but was certainly no match for it 1 All dates in the article pertain to the events before the birth of Christ except where otherwise stated. -

Xenophon's Theory of Moral Education Ix

Xenophon’s Theory of Moral Education Xenophon’s Theory of Moral Education By Houliang Lu Xenophon’s Theory of Moral Education By Houliang Lu This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Houliang Lu All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6880-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6880-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................... vii Editions ..................................................................................................... viii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Background of Xenophon’s Thought on Moral Education Chapter One ............................................................................................... 13 Xenophon’s View of His Time Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 41 Influence of Socrates on Xenophon’s Thought on Moral Education Part II: A Systematic Theory of Moral Education from a Social Perspective Chapter One .............................................................................................. -

The Relationship Between the Western Satraps and the Greeks

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018-11-08 East Looking West: the Relationship between the Western Satraps and the Greeks Ward, Megan Leigh Falconer Ward, M. L. F. (2018). East Looking West: the Relationship between the Western Satraps and the Greeks (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/33255 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/109170 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY “East Looking West: the Relationship between the Western Satraps and the Greeks.” by Megan Leigh Falconer Ward A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GREEK AND ROMAN STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA NOVEMBER, 2018 © Megan Leigh Falconer Ward 2018 Abstract The satraps of Persia played a significant role in many affairs of the European Greek poleis. This dissertation contains a discussion of the ways in which the Persians treated the Hellenic states like subjects of the Persian empire, particularly following the expulsion of the Persian Invasion in 479 BCE. Chapter One looks at Persian authority both within the empire and among the Greeks. -

Epicurus on Socrates in Love, According to Maximus of Tyre Ágora

Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em debate ISSN: 0874-5498 [email protected] Universidade de Aveiro Portugal CAMPOS DAROCA, F. JAVIER Nothing to be learnt from Socrates? Epicurus on Socrates in love, according to Maximus of Tyre Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em debate, núm. 18, 2016, pp. 99-119 Universidade de Aveiro Aveiro, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=321046070005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Nothing to be learnt from Socrates? Epicurus on Socrates in love, according to Maximus of Tyre Não há nada a aprender com Sócrates? Epicuro e os amores de Sócrates, segundo Máximo de Tiro F. JAVIER CAMPOS DAROCA (University of Almería — Spain) 1 Abstract: In the 32nd Oration “On Pleasure”, by Maximus of Tyre, a defence of hedonism is presented in which Epicurus himself comes out in person to speak in favour of pleasure. In this defence, Socrates’ love affairs are recalled as an instance of virtuous behaviour allied with pleasure. In this paper we will explore this rather strange Epicurean portrayal of Socrates as a positive example. We contend that in order to understand this depiction of Socrates as a virtuous lover, some previous trends in Platonism should be taken into account, chiefly those which kept the relationship with the Hellenistic Academia alive. Special mention is made of Favorinus of Arelate, not as the source of the contents in the oration, but as the author closest to Maximus both for his interest in Socrates and his rhetorical (as well as dialectical) ways in philosophy. -

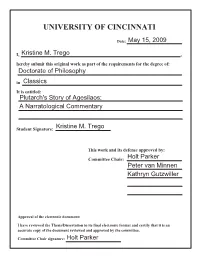

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do. -

Sean Manning, a Prosopography of the Followers of Cyrus the Younger

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME THIRTY-TWO: 2018 NUMBERS 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson ò Michael Fronda òDavid Hollander Timothy Howe òJoseph Roisman ò John Vanderspoel Pat Wheatley ò Sabine Müller òAlex McAuley Catalina Balmacedaò Charlotte Dunn ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 32 (2018) Numbers 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Assistant Editor: Charlotte Dunn Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume thirty-two Numbers 1-2 1 Sean Manning, A Prosopography of the Followers of Cyrus the Younger 25 Eyal Meyer, Cimon’s Eurymedon Campaign Reconsidered? 44 Joshua P. Nudell, Alexander the Great and Didyma: A Reconsideration 61 Jens Jakobssen and Simon Glenn, New research on the Bactrian Tax-Receipt NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Leuven), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel and Pat Wheatley. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

Innovation and Conceptual Innovation in Ancient Greece Benoît Godin

Innovation and Conceptual Innovation in Ancient Greece Benoît Godin with the collaboration of Pierre Lucier INRS Chaire Fernand Dumont sur la Culture Project on the Intellectual History of Innovation Working Paper No. 12 2012 Previous Papers in the Series 1. B. Godin, Innovation: the History of a Category. 2. B. Godin, In the Shadow of Schumpeter: W. Rupert Maclaurin and the Study of Technological Innovation. 3. B. Godin, The Linear Model of Innovation (II): Maurice Holland and the Research Cycle. 4. B. Godin, National Innovation System (II): Industrialists and the Origins of an Idea. 5. B. Godin, Innovation without the Word: William F. Ogburn’s Contribution to Technological Innovation Studies. 6. B. Godin, ‘Meddle Not with Them that Are Given to Change’: Innovation as Evil. 7. B. Godin, Innovation Studies: the Invention of a Specialty (Part I). 8. B. Godin, Innovation Studies: the Invention of a Specialty (Part II). 9. B. Godin, καινοτομία: An Old Word for a New World, or the De-Contestation of a Political and Contested Concept. 10. B. Godin, Innovation and Politics: The Controversy on Republicanism in Seventeenth Century England. 11. B. Godin, Social Innovation: Utopias of Innovation from circa-1830 to the Present. Project on the Intellectual History of Innovation 385 rue Sherbrooke Est, Montréal, Quebec H2X 1E3 Telephone: (514) 499-4074; Facsimile: (514) 499-4065 www.csiic.ca 2 Abstract The study of political thought and the history of political ideas are concerned with concepts such as sovereignty, liberty, virtue, republic, democracy, constitution, state and revolution. “Innovation” is not part of this vocabulary. Yet, innovation is a political concept, first of all in the sense that it is a preoccupation of statesmen for centuries: innovation is regulated by Kings, forbidden by law and punished. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 61 3rd International Symposium on Social Science (ISSS 2017) The Study of Two International (Regional) Systems before and after the Greco-Persian Wars Ming Guoa Macau University of Science and Technology, 999078, Macau Guangdong Institute of Science and Technology, Zhuhai, 519000, China [email protected] Abstract. The Greek wave of 499 BC to 449 BC was a series of wars and conflicts that erupted between the ancient Greek city and the eastern Persian. Through the analysis and combing of the reasons for the Greco-Persian war, try to dig out the city, and the eastern Persian Greek two area (International) power system, different form system and culture, in order to more clearly show that before and after the Greco-Persian war, ancient Greece and Eastern Persian International (regional) some of the attributes of the system provide benefits for better understanding, fifth Century - fourth Century BC the eastern and western regions. Keywords: the Greco-Persian Wars, International (regional) systems. 1. Introduction The fifth century BC, Greece and Persia as the two most typical civilization on the Mediterranean, has been aroused the interest of academia and people. The conflict and communication between them not only have a profound impact on the historical development of each other, but also affect the development of the world history and regional trends. The rise of the Persian nation in the Iranian plateau is a branch of the Indo-European tribe of the Aryanian tribe, which first lived on the prairies of the Eurasian continent and the Aral Sea to the south, and then moved southward to the Mesopotamian plain North. -

Oikonomia As a Theory of Empire in the Political Thought of Xenophon and Aristotle Grant A

Oikonomia as a Theory of Empire in the Political Thought of Xenophon and Aristotle Grant A. Nelsestuen ROM AT LEAST HERODOTUS (5.29) onwards, the house- hold (oikos) and its management (oikonomia) served as im- portant conceptual touchstones for Greek thought about F 1 the polis and the challenges it faces. Consider the exchange between Socrates and a certain Nicomachides in Xenophon’s Memorabilia 3.4. In response to Nicomachides’ complaint that the Athenians selected as general a man with no experience in warfare but who is a good “household manager” (oikonomos, 3.4.7, cf. 3.4.11), Socrates maintains that oikonomia and management of public affairs differ only in “scale” and are “quite close in all other respects”: skill in the one task readily transfers to the other because each requires “knowing how to 2 make use of ” (epistamenoi chrēsthai) people. A more sophisticated version of this argument appears in Plato’s Politicus (258E4– 259D5) when the Elean stranger elicits Socrates’ agreement 1 See R. Brock, Greek Political Imagery (London 2013) 25–42, for an over- view of household imagery applied to the polis. For concise definitions of the Greek oikos see L. Foxhall, “Household, Gender and Property in Classical Athens,” CQ 39 (1989) 29–31; D. B. Nagle, The Household as the Foundation of Aristotle’s Polis (Cambridge 2006) 15–18; and S. Pomeroy, Xenophon Oecono- micus. A Social and Historical Commentary (Oxford 1994) 213–214. C. A. Cox, Household Interests. Property, Marriage Strategies, and Family Dynamics in Ancient Athens (Princeton 1998) 130–167, judiciously evaluates the Oeconomicus’ con- ception of the oikos against other literary and material evidence.