A Level Ancient History Candidate Style Answers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anton Powell, Nicolas Richer (Eds.), Xenophon and Sparta, the Classical Press of Wales, Swansea 2020, 378 Pp.; ISBN 978-1-910589-74-8

ELECTRUM * Vol. 27 (2020): 213–216 doi:10.4467/20800909EL.20.011.12801 www.ejournals.eu/electrum Anton Powell, Nicolas Richer (eds.), Xenophon and Sparta, The Classical Press of Wales, Swansea 2020, 378 pp.; ISBN 978-1-910589-74-8 The reviewed book is a collection of twelve papers, previously presented at the confe- rence organised by École Normale Supérieure in Lyon in 2006. According to the edi- tors, this is a first volume in the planned series dealing with sources of Spartan his- tory. The books that follow this will deal with the presence of this topic in works by Thucydides, Herodotus, Plutarch, and in archaeological material. The decision to start the cycle from Xenophon cannot be considered as surprising; this ancient author has not only written about Sparta, but also had opportunities to visit the country, person- ally met a number of its officials (including king Agesilaus), and even sent his own sons for a Spartan upbringing. Thus his writings are widely considered as our best source to the history of Sparta in the classical age. Despite this, Xenophon’s literary work remains the subject of numerous controver- sies in discussions among modern scholars. The question of his objectivity is especial- ly problematic and the views about the strong partisanship of Xenophon prevailed for a long time; allegedly, he was depicting Sparta and king Agesilaus in a possibly overly positive light, even omitting inconvenient information.1 In the second half of the 20th century such opinion has been met with a convincing polemic, clearly seen in the works of H. -

Xenophon's Theory of Moral Education Ix

Xenophon’s Theory of Moral Education Xenophon’s Theory of Moral Education By Houliang Lu Xenophon’s Theory of Moral Education By Houliang Lu This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Houliang Lu All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6880-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6880-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................... vii Editions ..................................................................................................... viii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Background of Xenophon’s Thought on Moral Education Chapter One ............................................................................................... 13 Xenophon’s View of His Time Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 41 Influence of Socrates on Xenophon’s Thought on Moral Education Part II: A Systematic Theory of Moral Education from a Social Perspective Chapter One .............................................................................................. -

The Relationship Between the Western Satraps and the Greeks

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018-11-08 East Looking West: the Relationship between the Western Satraps and the Greeks Ward, Megan Leigh Falconer Ward, M. L. F. (2018). East Looking West: the Relationship between the Western Satraps and the Greeks (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/33255 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/109170 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY “East Looking West: the Relationship between the Western Satraps and the Greeks.” by Megan Leigh Falconer Ward A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GREEK AND ROMAN STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA NOVEMBER, 2018 © Megan Leigh Falconer Ward 2018 Abstract The satraps of Persia played a significant role in many affairs of the European Greek poleis. This dissertation contains a discussion of the ways in which the Persians treated the Hellenic states like subjects of the Persian empire, particularly following the expulsion of the Persian Invasion in 479 BCE. Chapter One looks at Persian authority both within the empire and among the Greeks. -

Epicurus on Socrates in Love, According to Maximus of Tyre Ágora

Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em debate ISSN: 0874-5498 [email protected] Universidade de Aveiro Portugal CAMPOS DAROCA, F. JAVIER Nothing to be learnt from Socrates? Epicurus on Socrates in love, according to Maximus of Tyre Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em debate, núm. 18, 2016, pp. 99-119 Universidade de Aveiro Aveiro, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=321046070005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Nothing to be learnt from Socrates? Epicurus on Socrates in love, according to Maximus of Tyre Não há nada a aprender com Sócrates? Epicuro e os amores de Sócrates, segundo Máximo de Tiro F. JAVIER CAMPOS DAROCA (University of Almería — Spain) 1 Abstract: In the 32nd Oration “On Pleasure”, by Maximus of Tyre, a defence of hedonism is presented in which Epicurus himself comes out in person to speak in favour of pleasure. In this defence, Socrates’ love affairs are recalled as an instance of virtuous behaviour allied with pleasure. In this paper we will explore this rather strange Epicurean portrayal of Socrates as a positive example. We contend that in order to understand this depiction of Socrates as a virtuous lover, some previous trends in Platonism should be taken into account, chiefly those which kept the relationship with the Hellenistic Academia alive. Special mention is made of Favorinus of Arelate, not as the source of the contents in the oration, but as the author closest to Maximus both for his interest in Socrates and his rhetorical (as well as dialectical) ways in philosophy. -

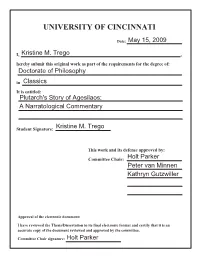

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do. -

Lives in Poetry

LIVES IN POETRY John Scales Avery March 25, 2020 2 Contents 1 HOMER 9 1.1 The little that is known about Homer's life . .9 1.2 The Iliad, late 8th or early 7th century BC . 12 1.3 The Odyssey . 14 2 ANCIENT GREEK POETRY AND DRAMA 23 2.1 The ethical message of Greek drama . 23 2.2 Sophocles, 497 BC - 406 BC . 23 2.3 Euripides, c.480 BC - c.406 BC . 25 2.4 Aristophanes, c.446 BC - c.386 BC . 26 2.5 Sapho, c.630 BC - c.570 BC . 28 3 POETS OF ANCIENT ROME 31 3.1 Lucretius, c.90 BC - c.55 BC . 31 3.2 Ovid, 43 BC - c.17 AD . 33 3.3 Virgil, 70 BC - 19 AD . 36 3.4 Juvenal, late 1st century AD - early 2nd century AD . 40 4 THE GOLDEN AGE OF CHINESE POETRY 45 4.1 The T'ang dynasty, a golden age for China . 45 4.2 Tu Fu, 712-770 . 46 4.3 Li Po, 701-762 . 48 4.4 Li Ching Chao, 1081-c.1141 . 50 5 JAPANESE HAIKU 55 5.1 Basho . 55 5.2 Kobayashi Issa, 1763-1828 . 58 5.3 Some modern haiku in English . 60 6 POETS OF INDIA 61 6.1 Some of India's famous poets . 61 6.2 Rabindranath Tagore, 1861-1941 . 61 6.3 Kamala Surayya, 1934-2009 . 66 3 4 CONTENTS 7 POETS OF ISLAM 71 7.1 Ferdowsi, c.940-1020 . 71 7.2 Omar Khayyam, 1048-1131 . 73 7.3 Rumi, 1207-1273 . -

Sparta Made a Sian Fleet Off Cecryphalea, Between Epidaurus and Aegina

3028 land at Halieis in Argolis but victorious against a Peloponne- to back out of her alliance with Athens, and Sparta made a sian fleet off Cecryphalea, between Epidaurus and Aegina. Thirty-year truce with Argos to clear its access to Attica Alarmed by this Athenian activity in the Saronic Gulf, Ae- gina entered the war against Athens. In 458 BC in a great sea After the Truce battle the Athenians captured seventy Aeginetan and Pelo- Freed from fighting in Greece, the Athenians sent a fleet of ponnesian ships, landed on the island, and laid siege to the two hundred ships, under Cimon, to campaign in Cyprus. Cit- town of Aegina. With substantial Athenian forces being tied ium in southeast Cyprus was besieged, but food shortage and down in Egypt and Aegina, Corinth judged it was a good time Cimon's death caused a general retreat northeastwards to Sa- to invade the Megarid. The Athenians scraped together a lamis. They were attacked by a Persian force of Cyprians, force of men too old and boys too young for ordinary military Phoenicians and Cilicians. The Athenians defeated this force service and sent it under the command of Myronides to re- by both land and sea then sailed back to Greece. lieve Megara. The resulting battle was indecisive, but the After Xerxes' invasion in 479 BC the Persians had continu- Athenians held the field at the end of the day. About twelve ally lost territory and by 450 BC they were ready to make days later the Corinthians returned to the site but the Atheni- peace. -

Innovation and Conceptual Innovation in Ancient Greece Benoît Godin

Innovation and Conceptual Innovation in Ancient Greece Benoît Godin with the collaboration of Pierre Lucier INRS Chaire Fernand Dumont sur la Culture Project on the Intellectual History of Innovation Working Paper No. 12 2012 Previous Papers in the Series 1. B. Godin, Innovation: the History of a Category. 2. B. Godin, In the Shadow of Schumpeter: W. Rupert Maclaurin and the Study of Technological Innovation. 3. B. Godin, The Linear Model of Innovation (II): Maurice Holland and the Research Cycle. 4. B. Godin, National Innovation System (II): Industrialists and the Origins of an Idea. 5. B. Godin, Innovation without the Word: William F. Ogburn’s Contribution to Technological Innovation Studies. 6. B. Godin, ‘Meddle Not with Them that Are Given to Change’: Innovation as Evil. 7. B. Godin, Innovation Studies: the Invention of a Specialty (Part I). 8. B. Godin, Innovation Studies: the Invention of a Specialty (Part II). 9. B. Godin, καινοτομία: An Old Word for a New World, or the De-Contestation of a Political and Contested Concept. 10. B. Godin, Innovation and Politics: The Controversy on Republicanism in Seventeenth Century England. 11. B. Godin, Social Innovation: Utopias of Innovation from circa-1830 to the Present. Project on the Intellectual History of Innovation 385 rue Sherbrooke Est, Montréal, Quebec H2X 1E3 Telephone: (514) 499-4074; Facsimile: (514) 499-4065 www.csiic.ca 2 Abstract The study of political thought and the history of political ideas are concerned with concepts such as sovereignty, liberty, virtue, republic, democracy, constitution, state and revolution. “Innovation” is not part of this vocabulary. Yet, innovation is a political concept, first of all in the sense that it is a preoccupation of statesmen for centuries: innovation is regulated by Kings, forbidden by law and punished. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 61 3rd International Symposium on Social Science (ISSS 2017) The Study of Two International (Regional) Systems before and after the Greco-Persian Wars Ming Guoa Macau University of Science and Technology, 999078, Macau Guangdong Institute of Science and Technology, Zhuhai, 519000, China [email protected] Abstract. The Greek wave of 499 BC to 449 BC was a series of wars and conflicts that erupted between the ancient Greek city and the eastern Persian. Through the analysis and combing of the reasons for the Greco-Persian war, try to dig out the city, and the eastern Persian Greek two area (International) power system, different form system and culture, in order to more clearly show that before and after the Greco-Persian war, ancient Greece and Eastern Persian International (regional) some of the attributes of the system provide benefits for better understanding, fifth Century - fourth Century BC the eastern and western regions. Keywords: the Greco-Persian Wars, International (regional) systems. 1. Introduction The fifth century BC, Greece and Persia as the two most typical civilization on the Mediterranean, has been aroused the interest of academia and people. The conflict and communication between them not only have a profound impact on the historical development of each other, but also affect the development of the world history and regional trends. The rise of the Persian nation in the Iranian plateau is a branch of the Indo-European tribe of the Aryanian tribe, which first lived on the prairies of the Eurasian continent and the Aral Sea to the south, and then moved southward to the Mesopotamian plain North. -

Fall/Winter 2019

FALL/WINTER 2019 RECENT ART + ARCHITECTURE HIGHLIGHTS ARCHITECTURE + ART RECENT $35.00 $55.00 $50.00 978-0-87633-289-4 $40.00 978-0-300-23328-5 978-1-58839-668-6 Hardcover 978-0-300-24269-0 Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Post-Impressionism Graphic Design Graphic CAMP Impressionism and and Impressionism Ruth Asawa Ruth Thompson Eskilson Bolton Schenkenberg Damrosch Yau/Nadis Starr Sexton The Club The Shape of A Life Entrenchment Standing for Reason Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover 978-0-300-21790-2 978-0-300-23590-6 978-0-300-23847-1 978-0-300-24337-6 $30.00 $28.00 $28.50 $26.00 $550.00 $35.00 978-0-300-24395-6 978-0-300-19195-0 $45.00 $65.00 PB-with Flaps PB-with Slipcase with Set - HC 978-0-300-23719-1 978-1-58839-665-5 HC - Paper over Board over Paper - HC Hardcover New Typography New Rediscovered The Power of Color of Power The Genji of Tale The the and Tschichold Jan Vinci da Leonardo Hall Carpenter/McCormick Stirton Bambach Winship Wilken Mackintosh-Smith Hoffman Hot Protestants Liberty in the Things Arabs Ben Hecht Hardcover of God HC - Paper over Board Hardcover 978-0-300-12628-0 Hardcover 978-0-300-18028-2 978-0-300-18042-8 $28.00 978-0-300-22663-8 $35.00 $26.00 $26.00 $40.00 $45.00 $75.00 $50.00 978-0-300-24273-7 978-0-300-23344-5 978-0-300-24365-9 978-1-58839-666-2 HC - Paper over Board over Paper - HC Cloth over Board over Cloth Hardcover Hardcover Gauguin Yves Saint Laurent Saint Yves Loud it Play Archive for is A Homburg/Riopelle Bolton Dobney/Inciardi Wrbican Antoon Popoff Jones-Rogers Brands/Edel The Book of Vasily Grossman and They Were Her The Lessons of Collateral Damage the Soviet Century Property Tragedy Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover 978-0-300-22894-6 978-0-300-22278-4 978-0-300-21866-4 978-0-300-23824-2 $24.00 $32.50 $30.00 $25.00 RECENT GENERAL INTEREST HIGHLIGHTS Yale university press FALL / WINTER 2019 GENERAL INTEREST 1 JEWISH LIVES 28 MARGELLOS WORLD REPUBLIC OF LETTERS 32 SCHOLARLY AND ACADEMIC 63 PAPERBACK REPRINTS 81 ART + ARCHITECTURE A1 cover: Illustration by Tom Duxbury, represented by Artist Partners. -

The Causes of the Peloponnesian War by Jared Mckinney

©Classics of Strategy & Diplomacy1 Structure and Contingency: The Causes of the Peloponnesian War by Jared McKinney Thucydides called it “a war like no other” (1.23.1, trans. Hanson, 2005). It was a 27 year war that brought an end to the fifth century Athenian Golden Age, killed more Greeks in one year than the Persians killed in ten (Hanson, 2005, p. 11), and, in the end, seemed to solve nothing. “Never before had so many cities been captured and then devastated . ; never had there been so many exiles; never such loss of life” (1.23, trans. Warner, 1972). Such was the severity of war that words lost their meanings. Aggression became courage; prudence became cowardice; moderation became unmanly; understanding was mocked; “fanatical enthusiasm was the mark of a real man . Anyone who held violent opinions could always be trusted, and anyone who objected to them became suspect” (1.82). Greeks, in effect reentering what moderns might call a state of nature, became barbarians. It was in such an environment shortly after the conclusion of the war that Socrates himself—though he fought bravely during the war—was executed (Hanson, 2005, p. 5).* What caused this war? The Greeks themselves were unsure: “As for the war in which they [Athens and Sparta] are engaged, they are not certain who began it,” Thucydides has Spartan delegates declare in a speech to the Athenians (4.20). But with so much devastation and pain, not knowing seemed unacceptable. And so it was that Thucydides (c. 460- c. 400 BC), who was himself an Athenian veteran of the war, undertook the first sustained inquiry in history into the origins and course of a single war (Finley, 1972, p. -

Oikonomia As a Theory of Empire in the Political Thought of Xenophon and Aristotle Grant A

Oikonomia as a Theory of Empire in the Political Thought of Xenophon and Aristotle Grant A. Nelsestuen ROM AT LEAST HERODOTUS (5.29) onwards, the house- hold (oikos) and its management (oikonomia) served as im- portant conceptual touchstones for Greek thought about F 1 the polis and the challenges it faces. Consider the exchange between Socrates and a certain Nicomachides in Xenophon’s Memorabilia 3.4. In response to Nicomachides’ complaint that the Athenians selected as general a man with no experience in warfare but who is a good “household manager” (oikonomos, 3.4.7, cf. 3.4.11), Socrates maintains that oikonomia and management of public affairs differ only in “scale” and are “quite close in all other respects”: skill in the one task readily transfers to the other because each requires “knowing how to 2 make use of ” (epistamenoi chrēsthai) people. A more sophisticated version of this argument appears in Plato’s Politicus (258E4– 259D5) when the Elean stranger elicits Socrates’ agreement 1 See R. Brock, Greek Political Imagery (London 2013) 25–42, for an over- view of household imagery applied to the polis. For concise definitions of the Greek oikos see L. Foxhall, “Household, Gender and Property in Classical Athens,” CQ 39 (1989) 29–31; D. B. Nagle, The Household as the Foundation of Aristotle’s Polis (Cambridge 2006) 15–18; and S. Pomeroy, Xenophon Oecono- micus. A Social and Historical Commentary (Oxford 1994) 213–214. C. A. Cox, Household Interests. Property, Marriage Strategies, and Family Dynamics in Ancient Athens (Princeton 1998) 130–167, judiciously evaluates the Oeconomicus’ con- ception of the oikos against other literary and material evidence.