The Many Lives of Pablo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

News 2-9-11.Indd

www.thedavidsonian.com DAVI D SON COLLEGE WE D NES D AY , FEBRUARY 9, 2011 VOLUME 102, NUMBER 15 “Dash for Davidson” Meets Success Chambers Bell KATIE LOVETT Staff Writier Chimes Again The “Dash for Davidson” campaign re- ceived a much-anticipated victory Monday night as Gerard Dash ’12 was named the Student Government Association’s (SGA) President for the 2011-2012 academic year. Yet, long before this year’s initial interest meeting for Category II Elections on January 25th, Dash had been committed to making his mark upon the Davidson community. Dash dedicated the first three years of his Davidson career to service for the SGA. His past positions include Freshman Class Senator ERI C SA W YER (2008-2009), Council Chairman (2009-2010) Staff Writer and Student Body Vice President alongside President Kevin Hubbard (2010-2011). In ad- Last week the Chambers bell stopped dition to these roles, he served on official col- ringing, and members of the Physical Plant lege committees, such as the Strategic Plan corrected the problem in several days. The Implementation Team, Council for Campus bell has been inoperative in the past for vary- and Religious Life (CCRL), National Pan- ing lengths of time. It was donated to the col- Hellenic Council Expansion Committee and lege in 1922 to replace its predecessor, which Public Safety Committee, while also holding was destroyed when the old Chambers build- the position of Union Board Treasurer from ing burned down in 1921. 2009 to 2010. “All mechanical equipment will fail from The recently elected president’s experi- time to time,” said Jerry Archer, Physical ence can be seen in the many changes he has Plant. -

Impaired Driving: Case Law Review 2017

Volume 26 February 2017 No. 3 © 2017 Texas Municipal Courts Education Center. Funded by a grant from the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. Impaired Driving: Case Law Review 2017 Ryan Kellus Turner Regan Metteauer General Counsel and Director of Education Program Attorney TMCEC TMCEC The following decisions and opinions were issued between the dates of October 1, 2015 and October 1, 2016 except where noted (*). Acknowledgment: Thank you Judge David Newell, Courtney Corbello, Benjamin Gibbs, Carmen Roe, Stacey Soule, and Randy Zamora. Your insight and assistance helped us bring this paper to fruition. The search incident to arrest doctrine does not apply to warrantless blood draws, but it does apply to warrantless breath tests. Birchfield v. North Dakota, 136 S. Ct. 2160 (2016) In a 5-3 decision, the Court examined three consolidated cases involving state laws criminalizing refusal to take warrantless tests measuring blood alcohol concentration (BAC). All three defendants were arrested for drunk driving. Defendants Birchfield (North Dakota) and Beylund (North Dakota) received warnings Case Law Update continued on pg. 3 Community Service: Inside This Issue Suggested Practices and Potential 800-Line Guidelines ..................... 40 Problem Areas Academic Schedule ....................... 39 Court Security Specialist Certification .................................. 31 Molly Knowles, Communications Assistant, TMCEC DRSR Selected for Award ............ 2 Ethics Update ................................ 19 Community Service: An Alternative Mean From the Center ............................ 35 Impaired Driving DVDs ............... 27 In Tate v. Short (1971), the Supreme Court of the United States held that MTSI Conference ......................... 32 the Equal Protection Clause prohibits converting fines to jail time solely OCA Annual Report ...................... 33 because the defendant is indigent.1 Prior to Tate v. -

Mustang Daily, January 14, 1991

Mustang Daily California Polytechnic State university San Luis Obispo Volurrie 55, No.48 Monday, January 14,1991 ‘Walk for Peace’ unites local residents in anti-war \ U n 7 ' protest during weekend □ More than 2,000 rally in opposition to Gulf Intervention. By Grant A. Landy Amendment rights of freedom of speech,” stall WrKer he said, starting a loud roar of applause. A wave of protest enveloped “America’s strength lies in the separation downtown San Luis Obispo of powers and the system of checks and Saturday morning as more balances guaranteed by the Constitution,” Krejsa said in his statement. ‘There is no than 2,000 people packed the County Gov constitutional guarantee that the ernment Center for the “Walk For Peace” Legislative branch must act foolishly movement against possible war in the Middle East. whenever the Executive branch does. It is not the duty of Congress to rescue the While a soothing Tracy Chapman tune president from his own ineptitude. It is filled the air, more and more concerned Congress’s duty to show restraint when the people including mothers, grandfathers, President does not.” students, professors and children flooded By 11:30 the inspiring music of local tal the area in protest, eagerly awaiting a ents Mark Welsh and Erin Noble sent the journey that would flood the downtown marchers on their peace walk, down streets with demonstration. Monterey Street to Chorro Street, across to People carried signs bearing such state Higuera Street, down one side of Higuera ments as “Give Peace A Chance” and to Nipomo, then up Higuera’s other side to ,‘Blood is Red, Oil is Black.” A red-faced Santa Rosa Street before flooding back into ^rl held a sign saying “Bush, Stop Saving the County Government Center. -

Recognizing Song–Based Blink Patterns: Applications for Restricted and Universal Access

Recognizing Song–Based Blink Patterns: Applications for Restricted and Universal Access Tracy Westeyn & Thad Starner GVU, College of Computing Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, GA 30332 fturtle, [email protected] Abstract ing failure [12]. However, such conditions do not hinder a person’s ability to blink. Research suggests that blink- We introduce a novel system for recognizing patterns of ing patterns, such as variations of Morse code, can be an eye blinks for use in assistive technology interfaces and se- effective form of communication for a certain population curity systems. First, we present a blink-based interface for of the disabled community [7]. However, there are draw- controlling devices. Well known songs are used as the ca- backs to Morse code based systems. On average, learning dence for the blinked patterns. Our system distinguishes be- Morse code requires 20 to 30 hours of training. In addi- tween ten similar patterns with 99.0% accuracy. Second, we tion to the training time, communication with Morse code present a method for identifying individual people based on is cognitively demanding for a novice [2]. While rates of the characteristics of how they perform a specific pattern thirty words per minute [7] can be achieved through me- (their “blinkprint”). This technique could be used in con- chanical devices for experienced telegraphers, it is not clear junction with face recognition for security systems. We are what communication rates can be achieved through blink- able to distinguish between nine individuals with 82.02% ing for the disabled population. accuracy based solely on how they blink the same pattern. -

Updates on IUOE 302 Concrete Pumpers Negotiations

Updates on IUOE 302 concrete pumpers negotiations DECEMBER 30, 2007 401(k)s vs. Defined-Benefit Pensions Summary on the membership’s vote on the contract pro- (Dec. 21 entry from Local 302’s Blog at www.iuoe302.org) posal from Brundage Bone, Pacific and Ralph’s: Last week, the U.S. Government Accountability Of- The voice of our membership was heard today. The em- fice released a report explaining how grim the retire- ployers’ proposal was seen by the membership for what it is ment outlook is for today’s teenagers. More than one -- a clear attempt to further degrade out of three American workers born in 1990 will have those working in the pumping in- zero dollars in a 401(k)-style savings plan when they dustry for another six years. reach retirement age, the report said. Why? When you’re young, you aren’t thinking The vote against the proposal about retirement. You’re thinking about what you’re was nearly unanimous among the doing that weekend – or who you’re doing it with. pumpers at two companies, and it That explains why, as the GAO report points out, many was rejected 2-to-1 by pumpers at young people don’t contribute to employer-matched 401(k)s when they have the opportunity. It comes out the third. of their paychecks, and that means less this weekend. We remind all members that Even those who do contribute to 401(k) savings plans if anyone who is management attends your Union meeting often pay the tax penalty and take that money out at and then threatens your job based on your comments or your some point, the GAO report says. -

Basic Training for Those Guiding Children Around the World to Follow Jesus Like the Twelve Disciples

Basic training for those guiding children around the world to follow Jesus like the twelve disciples Part of the 1 for 50 family of training resources Table of Contents CORE LESSON OPTIONS (1 hour each) 1-0 Jesus’ Heart for Children 2-0 Jesus and the Children’s Leader 3-0 Characteristics of Children 4-0 Building Relationships with Children 5-0 Preparing to Teach Children 6-0 Building Bridges of Holistic Outreach to Children 7-0 Presenting the Gospel to Children 8-0 Talking with Children about Following Christ 9-0 Helping Children Grow as Disciples 10-0 Helping Children Experience God’s Word 11-0 Engaging Families 12-0 Building the Kingdom Together (networking/partnership) ENRICHMENT/EXTRA LESSONS (30 minutes each) 3-1 Needs of A Child 3-2 Understanding Our Children’s World 3-3 Considering children in Crisis 4-1 Communicating with Children 4-2 Building Relationships with Children through Play 4-3 Conversation Starters 5-1 Managing Classroom Behavior 6-1 Outreach Ideas 6-2 Overcoming Outreach Obstacles 7-1 More Gospel Tools 8-1 Answering Children’s Difficult Questions 9-1 Prayer Experiences for Children 9-2 Worship Experiences for Children 9-3 Helping Children Share Jesus with others 9-4 Growing Attitudes of the Disciples 9-5 Involving Children in God’s Big Story 10-1 Object Lessons-Demonstrations 10-2 Preparing and Presenting a Bible Story 10-3 More Bible Verse Ideas 10-4 Drama Experiences 10-5 Classroom Games 11-1 Spiritual Growth for Families 11-2 Outreach Ideas for Families 12-1 Connecting with the Church in Your Community 12-2 Involving Children in the church Instructor’s Guide LESSON 1-0 Jesus’ Heart for Children Objectives Participants will need: ñ To discover what scripture says about Jesus’ heart for children and the ñ Bibles world. -

TIME and ETHOS in RHETORICAL THEORY Collin Bjork Submitted To

ACCUMULATING CHARACTER: TIME AND ETHOS IN RHETORICAL THEORY Collin Bjork Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English, Indiana University June 2019 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Chair: Dana Anderson, Ph.D. __________________________________________ John Schilb, Ph.D. __________________________________________ Justin Hodgson, Ph.D. __________________________________________ Freya Thimsen, Ph.D. __________________________________________ Scot Barnett, Ph.D. 2 May 2019 ii Acknowledgements I am incredibly thankful for the long list of people and places that have impacted the direction and contours of this dissertation. And in a project that engages the imbricated concepts of character and time, I am particularly grateful for those who gave their own time to contribute to the ongoing development of my ethos as a scholar, teacher, and community member. I am thankful first for the public libraries that provided a quiet yet communal space in which to write: the Monroe Country Public Library, Ector County Public Library, Round Rock Public Library, Cedar Park Public Library, Austin Public Library, and Ghent Public Library. Your community-based work shares many important aims with the field of rhetoric that I now call home. I look forward to more opportunities to collaborate with you and other public libraries in the future. I am also grateful for the many universities that made their libraries and classrooms available for my thinking, writing, and teaching: Indiana University, the University of Texas at Austin, the University of Texas Permian Basin, Texas A&M University, Texas State University, Southwestern University, and Austin Community College. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

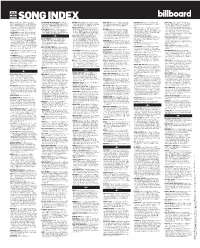

2021 Song Index

FEB 20 2021 SONG INDEX 100 (Ozuna Worldwide, BMI/Songs Of Kobalt ASTRONAUT IN THE OCEAN (Harry Michael BOOKER T (RSM Publishing, ASCAP/Universal DEAR GOD (Bethel Music Publishing, ASCAP/ FIRE FOR YOU (SarigSonnet, BMI/Songs Of GOOD DAYS (Solana Imani Rowe Publishing Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI/Music By Publishing Deisginee, APRA/Tyron Hapi Publish- Music Corp., ASCAP/Kid From Bklyn Publishing, Cory Asbury Publishing, ASCAP/SHOUT! MP Kobalt Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI) Designee, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ RHLM Publishing, BMI/Sony/ATV Latin Music ing Designee, APRA/BMG Rights Management ASCAP/Irving Music, Inc., BMI), HL, LT 14 Brio, BMI/Capitol CMG Paragon, BMI), HL, RO 23 Carter Lang Publishing Designee, BMI/Zuma Publishing, LLC, BMI/A Million Dollar Dream, (Australia) PTY LTD, APRA) RBH 43 BOX OF CHURCHES (Lontrell Williams Publish- CST 50 FIRES (This Little Fire, ASCAP/Songs For FCM, Tuna LLC, BMI/Warner-Tamerlane Publishing ASCAP/WC Music Corp., ASCAP/NumeroUno AT MY WORST (Artist 101 Publishing Group, ing Designee, ASCAP/Imran Abbas Publishing DE CORA <3 (Warner-Tamerlane Publishing SESAC/Integrity’s Alleluia! Music, SESAC/ Corp., BMI/Ruelas Publishing, ASCAP/Songtrust Publishing, ASCAP), AMP/HL, LT 46 BMI/EMI Pop Music Publishing, GMR/Olney Designee, GEMA/Thomas Kessler Publishing Corp., BMI/Music By Duars Publishing, BMI/ Nordinary Music, SESAC/Capitol CMG Amplifier, Ave, ASCAP/Loshendrix Production, ASCAP/ 2 PHUT HON (MUSICALLSTARS B.V., BUMA/ Songs, GMR/Kehlani Music, ASCAP/These Are Designee, BMI/Slaughter -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Spotlight on Erie

From the Editors The local voice for news, Contents: March 2, 2016 arts, and culture. Different ways of being human Editors-in-Chief: Brian Graham & Adam Welsh Managing Editor: Erie At Large 4 We have held the peculiar notion that a person or Katie Chriest society that is a little different from us, whoever we Contributing Editors: The educational costs of children in pov- Ben Speggen erty are, is somehow strange or bizarre, to be distrusted or Jim Wertz loathed. Think of the negative connotations of words Contributors: like alien or outlandish. And yet the monuments and Lisa Austin, Civitas cultures of each of our civilizations merely represent Mary Birdsong Just a Thought 7 different ways of being human. An extraterrestrial Rick Filippi Gregory Greenleaf-Knepp The upside of riding downtown visitor, looking at the differences among human beings John Lindvay and their societies, would find those differences trivial Brianna Lyle Bob Protzman compared to the similarities. – Carl Sagan, Cosmos Dan Schank William G. Sesler Harrisburg Happenings 7 Tommy Shannon n a presidential election year, what separates us Ryan Smith Only unity can save us from the ominous gets far more airtime than what connects us. The Ti Summer storm cloud of inaction hanging over this neighbors you chatted amicably with over the Matt Swanseger I Sara Toth Commonwealth. drone of lawnmowers put out a yard sign supporting Bryan Toy the candidate you loathe, and suddenly they’re the en- Nick Warren Senator Sean Wiley emy. You’re tempted to un-friend folks with opposing Cover Photo and Design: The Cold Realities of a Warming World 8 allegiances right and left on Facebook.