PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Lee Hooker: King of the Boogie Opens March 29 at the Grammy Museum® L.A

JOHN LEE HOOKER: KING OF THE BOOGIE OPENS MARCH 29 AT THE GRAMMY MUSEUM® L.A. LIVE CONTINUING THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BIRTH OF LEGENDARY GRAMMY®-WINNING BLUESMAN JOHN LEE HOOKER, TRAVELING EXHIBIT WILL FEATURE RARE RECORDINGS AND UNIQUE ITEMS FROM THE HOOKER ESTATE; HOOKER'S DAUGHTERS, DIANE HOOKER-ROAN AND ZAKIYA HOOKER, TO APPEAR AT MUSEUM FOR SPECIAL OPENING NIGHT PROGRAM LOS ANGELES, CALIF. (MARCH 6, 2018) —To continue commemorating what would have been legendary GRAMMY®-winning blues artist John Lee Hooker’s 100th birthday, the GRAMMY Museum® will open John Lee Hooker: King Of The Boogie in the Special Exhibits Gallery on the second floor on Thursday, March 29, 2018. On the night of the opening, Diane Hooker-Roan and Zakiya Hooker, daughters of the late bluesman, will appear at the GRAMMY Museum for a special program. Presented in conjunction with the John Lee Hooker Estate and Craft Recordings, the exhibit originally opened at GRAMMY Museum Mississippi—Hooker's home state—in 2017, the year of Hooker's centennial. On display for a limited time only through June 2018, the exhibit will include, among other items: • A rare 1961 Epiphone Zephyr—one of only 13 made that year—identical to the '61 Zephyr played by John Lee Hooker. Plus, a prototype of Epiphone's soon-to-be-released Limited Edition 100th Anniversary John Lee Hooker Zephyr signature guitar • Instruments such as the Gibson ES-335, Hohner HJ5 Jazz, and custom Washburn HB35, all of which were played by Hooker • The Best Traditional Blues Recording GRAMMY Hooker won, with Bonnie Raitt, for "I'm In The Mood" at the 32nd Annual GRAMMY Awards in 1990 • Hooker's Best Traditional Blues Album GRAMMY for Don't Look Back, which was co-produced by Van Morrison and Mike Kappus and won at the 40th Annual GRAMMY Awards in 1998 • A letter to Hooker from former President Bill Clinton • The program from Hooker's memorial service, which took place on June 27, 2001, in Oakland, Calif. -

Chasing the Echoes in Search of John Lee Hooker’S Detroit by Jeff Samoray

Chasing the Echoes In search of John Lee Hooker’s Detroit by jeff samoray n September of 1948, John Lee Hooker strummed the chord bars, restaurants, shoeshine parlors and other businesses that made up that ignited the endless boogie. Like many Delta blues musicians the neighborhood — to make way for the Chrysler Freeway. The spot I of that time, Hooker had moved north to pursue his music, and he where Hooker’s home once stood is now an empty, weed-choked lot. was paying the bills through factory work. For five years he had been Sensation, Fortune and the other record companies that issued some of toiling as a janitor in Detroit auto and steel plants. In the evenings, he Hooker’s earliest 78s have long been out of business. Most of the musi- would exchange his mop and broom for an Epiphone Zephyr to play cians who were on the scene in Hooker’s heyday have died. rent parties and clubs throughout Black Bottom, Detroit’s thriving Hooker left Detroit for San Francisco in 1970, and he continued black community on the near east side. “doin’ the boogie” until he died in 2001, at age 83. An array of musi- Word had gotten out about Hooker’s performances — a distinct, cians — from Eric Clapton and Bonnie Raitt to the Cowboy Junkies primitive form of Delta blues mixed with a driving electric rhythm. and Laughing Hyenas — have covered his songs, yet, for all the art- After recording a handful of crude demos, he finally got his break. ists who have followed in Hooker’s footsteps musically, it’s not easy to Hooker was entering Detroit’s United Sound Systems to lay down his retrace his path physically in present-day Detroit. -

West Virginia Folklife Program Presents Concert with Ballad Singer Phyllis Marks, September 8 for Immediate Release Contact: Em

West Virginia Folklife Program Presents Concert with Ballad Singer Phyllis Marks, September 8 For Immediate Release Contact: Emily Hilliard 304.346.8500 August 30, 2016 [email protected] Charleston— On the evening of Thursday, September 8, The West Virginia Folklife Program, a project of the West Virginia Humanities Council, will present a concert by West Virginia ballad singer Phyllis Marks. The concert will be held from 5:30-7:30pm at the historic MacFarland-Hubbard House, headquarters of the West Virginia Humanities Council (1310 Kanawha Blvd. E) in Charleston. The free event will include a performance, question-answer session, and reception, and will be recorded and archived at the Library of Congress. Phyllis Marks, age 89, is according to folklorist Gerry Milnes the last active ballad singer in the state who “learned by heart” via oral transmission. Marks was recorded for the Library of Congress in 1978 and has performed for 62 years at the West Virginia State Folk Festival in her hometown of Glenville. Phyllis Marks is among West Virginia’s finest traditional musicians and a master of unaccompanied Appalachian ballad singing. Following her performance, Marks will give a brief interview with West Virginia University musicology professor and West Virginia native Travis Stimeling. “West Virginia Folklife Presents Ballad Singer Phyllis Marks” is supported by ZMM Architects & Engineers in Charleston and The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress’ 2016 Henry Reed Fund Award. Established in 2004 with an initial gift from founding AFC director Alan Jabbour, the fund provides small awards to support activities directly involving folk artists, especially when the activities reflect, draw upon, or strengthen the archival collections of the AFC. -

Wayfaring Strangers: the Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 13 6-10-2015 Wayfaring Strangers: The uM sical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. 361 pages. ISBN:978-1-4696-1822-7. Michael Newton University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation Newton, Michael (2015) "Wayfaring Strangers: The usicalM Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. 361 pages. ISBN:978-1-4696-1822-7.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 13. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. 361 pages. ISBN: 978-1-4696-1822-7. $39.95. Michael Newton, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill It has become an article of faith for many North Americans (especially white anglophones) that the pedigree of modern country-western music is “Celtic.” The logic seems run like this: country-western music emerged among people with a predominance of Scottish, Irish, and “Scotch-Irish” ancestry; Scotland and Ireland are presumably Celtic countries; ballads and the fiddle seem to be the threads of connectivity between these musical worlds; therefore, country-western music carries forth the “musical DNA” of Celtic heritage. -

Folklife Center News, Volume XVI, Number 3 (Summer 1994)

CENTER NEWS SUMMER 1994 • VOLUME XVI, NUMBER 3 American Folklife Center • The Library of Congress EDITOR'S NOTES Federal Cylinder Project Legacies Tel: 202 707-1740 Folklore is resilient; itworks in many Board of Trustees ways to keep tradition going. Occa sionally a little institutional help is Juris Ubans, Chair, Maine useful, however, as in the several Robert Malir, Jr., Vice-chair , Kansas cases described in this issue of Folklife Nina Archabal, Minnesota Center News. Lindy Boggs, Louisiana; Norvus Miller died on May 1, Washington, D.C. 1994. But the sixteen musicians in Carolyn Hecker, Maine the Kings of Harmony band he di Judith McCulloh, Illinois rected for seventeen years include The American Folklife Center Ex Officio Members two of his sons, who carry on the was created in 1976 by the U.S. Con James H. Billington, family musical tradition. Children gress to "preserve and present Librarian of Congress growing up in the House of Prayer, American folklife" through pro Robert McCormick Adams, Susan Levitas reports, "were encour grams of research, documentation, Secretan1 of the Smithsonian Institution aged to pick up instruments and sit archival preservation, reference ser Jane Alexander, Chairman, in with older bands." Many learn to vice, live performance, exhibition, play by "observation, imitation, and publication, and training. The Cen National Endowment for the Arts ter incorporates the Archive of Folk Sheldon Hackney, Chairman, inundation," elements in the pro Culture, which was established in National Endowment for the Humanities cess of traditional learning. the Music Division of the Library of Alan Jabbour, Director, RalphRinzlerdiedonJuly2, 1994. Congress in 1928, and is now one of American Folklife Center But the Festival of AmericanFolklife the largest collections of ethno on the National Mall he helped to establish in 1967 continues to attract graphic material from the United FOLKLIFE CENTER NEWS States and around the world. -

Interview with Alan Jabbour Regarding Sarah Gertrude Knott (FA 459)

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® FA Oral Histories Folklife Archives 1995 Interview with Alan Jabbour Regarding Sarah Gertrude Knott (FA 459) Manuscripts & Folklife Archives Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_fa_oral_hist Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, Folklore Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Folklife Archives, Manuscripts &, "Interview with Alan Jabbour Regarding Sarah Gertrude Knott (FA 459)" (1995). FA Oral Histories. Paper 669. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_fa_oral_hist/669 This Transcription is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in FA Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tape 1 of 1 Informant: Alan Jabbour Interviewer: Hillary Glatt Date: February 28, 1995 Location: Washington, D.C. Transcriber: Andrew Lee Sanyo Memo Scriber OOIAJ: And now I'm talking. Can you pick me up? HG: Yes. O.k. Here we are. It's Tuesday, February 28th and we're in Alan Jabbour's office at the American Folklife Center in Washington, D.C.. And we're here to talk about Sarah Gertrude Knott and the National Folk Festival. This is a joint project of the Kentucky Oral History Commission and Western Kentucky University. So, Dr. Jabbour, instead of delving right into Sarah, why don't we start with how you came to be involved in this whole thing, presentation of folk culture. AJ: The whole—how did I ever get to Washington? I was in graduate school at Duke University and thought I was going to be a medievalist but took a course in the ballad, a graduate seminar with Holger Nygard. -

Folklife Center News, Volume 7 Number 4

October-December 1984 The American Folklije Center at the Library oj Congress, Washington, D . C. Volume VII, Number 4 Square Dance To Be National Folk Dance? The Kalevala: 150th Anniversary Publications novels ofpioneer and ethnic romance, and that moral commitment. Further, my FOLKLIFE CENTER NEWS with fi'nding quaint people. I havefound correspondent is certainly right that that people who romance about the past the wider public cultivation of nostal a quarterly publication of tbe and about "old times" often do not really gia is sometimes attended by exploita American Folklife Center care about the people they are romanticiz tion of old-fashioned traditions in a ing about. They have no desire to help condescending or self-centered way. at tbe these people but are more interested in ad But the letter also hints at a difference Library of Congress vancing a personal ideal-a patronizing between folklorists and much of our ideal. Simply, tradition-bearers are used society in their fundamental view of Alan Jabbour, Director to fuel a personal fantasy. The truth of what is past, what is present, and how the tradition is lost in the shuffle and the they are related. Ray Dockstader, Deputy Director tradition-bearer eventually realizes he is Discussion of how folklorists deal Elena Bradunas being used by someone he thought was with past and present is complicated, Carl Fleischhauer a friend. curiously, by consensus within our Mary Hufford I'm a romantic at heart - I spentyears field. I am reminded, in a season of Folklife Specialists working in western North Carolina and political campaigns, of the commen Peter T. -

Folklife Center News, Volume 11 Number 1 (Winter 1989). American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

AMERICAN FOLKLIFE CENTER THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Winter 1989 Volume XI, Number 1 THE ORIGIN OF POLISH SATURDAY SCHOOLS IN CHICAGO By Margy McClain The following article is taken from " Eth nic Heritage and Language Schools in America, }} a new book from the American Folklife Center. " Information on how to order appears on pages 3 and 4. At the beginning of the twentieth century, when great waves of im migration brought thousands of Poles to the Chicago area, Poland did not exist as a nation. Poland had been par titioned in 1795, into areas controlled by Russia, Prussia, and Austria, and ethnic Poles referred to themselves as "Russian Poles" or "Austrian Poles." Language and the Roman Catholic religion, rather than nation ality, marked the Polish people. Early Polish immigrants to the United States defined themselves in much the same way, by language, eth nicity, regional origin, and religion. They were mostly peasants with little formal education. They came for eco- Continued on page 2 Jozef Zurczak, principal of the Pulaski School in Chicago, Illinois, at the time of the Folklife Center's 1982 Ethnic Heritage and Language Schools Project. Mr. Zurczak is shown here as a guest teacher for the combined first and second grade class. (ES82-AF88416-1-35A) Photo by Margy McClain POLISH SATURDAY dialects spoken by their parents and AMERICAN FOLKLIFE CENTER teachers. Immigrants arriving after THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SCHOOLS World War II were surprised to find Continued from page 1 Alan J abbour, Director many archaic words and grammatical Ray Dockstader, Deputy Director constructions preserved in the speech nomic reasons and worked hard so of the established Polish-American Carl Fleischhauer that their children might make it up community. -

The Ohio State University Emeritus Academy Newsletter: December, 2020

1 The Ohio State University Emeritus Academy Newsletter: December, 2020 Editor, Joseph F. Donnermeyer (Past Chair, EA Steering Committee) Here we are – already near the end of the semester. A trying time for faculty and students alike, given all of the restrictions associated with COVID-19. Yet, members of the OSU Emeritus Academy have sustained their scholarship, and throughout it all, continue to publish articles and books, present at conferences (most online), teach from a distance, and engage in a variety of other activities that bring recognition to the university. It really does prove the most famous line from the university’s oldest school song, Carmen Ohio – “how firm thy friendship.” In this December issue of the EA newsletter, we begin by featuring the work of each chair of the Academy’s Steering Committee since its establishment in 2014 under the leadership of Terry Miller (Emeritus Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry), and up through the chair for next academic year, William Ausich (Professor Emeritus of Earth Sciences). Two editions of the EA newsletter will be issued during the Spring Semester. KEEP IN MIND THAT THE DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSIONS ABOUT YOUR SCHOLARLY ACTIVITIES WILL BE JANUARY 31. As a reminder, be sure to write your narrative in a style so that EA members from all of the disciplines can appreciate your work. Even though our lecture series is now via zoom until such time as restrictions on access to the campus associated with COVID-19 are lifted, the zoom version of the lectures remain well attended. In fact, on a couple of occasions, the number of participants was higher than usual. -

Folklore Joumal

Folklore Joumal .s, I 8 ucrj � z0 North Carolina Folklore Journal Philip E. (Ted) Coyle, Editor Dawn Kurry, Assistant Editor Thomas McGowan, Production Editor The North Carolina Folklore Journal is published twice a year by the North Carolina Folklore Society with assistance from Western Carolina University, Appalachian State University, and a grant from the North Carolina Arts Coun cil, an agency funded by the State of North Carolina and the National Endow ment for the Arts. Editorial Advisory Board (2006-2009) Barbara Duncan, Museum of the Cherokee Indian Alan Jabbour, American Folklife Center (retired) Erica Abrams Locklear, University of North Carolina at Asheville Thomas McGowan, Appalachian State University Carmine Prioli, North Carolina State University Kim Turnage, Lenoir Community College The North Carolina Folklore Journalpublishes studies of North Carolina folk lore and folklife, analyses of folklore in Southern literature, and articles whose rigorous or innovative approach pertains to local folklife study. Manuscripts should conformto The MLA StyleManual. Quotations from oral narrativesshould be transcriptions of spoken texts and should be identified by informant, place, and date. For information regarding submissions, view our website (http:/ paws.wcu.edu/ncfj), or contact: Dr. Philip E. Coyle Department of Anthropology and Sociology Western Carolina University Cullowhee, NC 28723 North Carolina Folklore Society 2010 Offlcers Barbara Lau, Durham, President Lora Smith, Pittsboro, 1st Vice President Shelia Wilson, Burlington, 2nd Vice President Steve Kruger, Hillsborough, 3rd Vice President Joy M. Salyers, Hillsborough, Secretary Janet Hoshour, Hillsborough, Treasurer North Carolina Folklore Society memberships are $20 per year for individuals; student memberships are $15. Annual institutional and overseas memberships are $25. -

Complete John Lee Hooker Session Discography

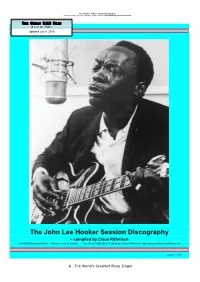

The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography: from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info The Great R&B Files (# 2 of 12) PaRT i Updated July 8, 2019 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography - compiled by Claus Röhnisch The R&B Pioneers Series – Volume Two of twelve The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info page 1 (94) 1 The World’s Greatest Blues Singer The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography: from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info The John Lee Hooker Session Discography - compiled by Claus Röhnisch John Lee Hooker – The World’s Greatest Blues Singer / The R&B Pioneers Series – Volume Two of twelve Below: Hooker’s first record, his JVB single of 1953, and the famous “Boom Boom”. The “Hooker” Box, Vee-Jay’s version of the Hooker classic, the original “The Healer” album on Chameleon. BluesWay 1968 single “Mr. Lucky”, the Craft Recordings album of March 2017, and the French version of the Crown LP “The Blues”. Right: Hooker in his prime. Two images from Hooker’s grave in the Chapel of The Chimes, Oakland, California; and a Mississippi Blues Trail Marker on Hwy. 3 in Quitman County (Vance, Missisippi memorial stone - note birth date c. 1917). 2 The World’s Greatest Blues Singer The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography: from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info . December 31, 1948 (probably not, but possibly early 1949) - very rare (and very early) publicity photo of the new-found Blues Star (playin’ his Gibson ES 175). -

Complete John Lee Hooker Session Discography

The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography –Part II from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info The Great R&B Files (# 2 of 12) Part II Updated 2017-09-23 MAIN CONTENTS: page Hooker Singles in Disguise 82 Hooker’s First and Last Albums 94 The Body & Soul CD-series 112 Giant of Blues – an Essay by Les Fancourt 114 The Complete EP Collection 118 The Real Best of Selection (with Trivia) 132 The three “whole career” double-CDs 137 JLH Recording Scale 138 Bootlegs and DVDs 142 Nuthin’ but the Best! – Fictional Album 145 The World’s Greatest Blues Singer Supplement to The John Lee Hooker Session Discography http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info/02_HookerSessionDiscography.pdf Part II of the John Lee Hooker Session Discography - compiled by Claus Röhnisch - The R&B Pioneers Series: Volume Two (Part II) of twelve The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info page 81 (of 164) The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography – Part II from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info The BEST of the CDs featuring Johnnie’s pirate recordings Check Ultimate CD’s entries in the Session Discography, Part One for more details ….. and check Singles discography for pseudonyms. ”Boogie Awhile” – Krazy Kat; ”Early Years: The Classic Savoy Sessions” (1948/49 and 1961) - MetroDoubles; ”Savoy Blues Legends: Detroit 1948-1949” – Savoy; ”Danceland Years” – Pointblank ”I’m A Boogie Man: The Essential Masters 1948-1953” – Varese Sarabande; ”The Boogie Man” – Properbox;