Boogie Chillen'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internet Killed the B-Boy Star: a Study of B-Boying Through the Lens Of

Internet Killed the B-boy Star: A Study of B-boying Through the Lens of Contemporary Media Dehui Kong Senior Seminar in Dance Fall 2010 Thesis director: Professor L. Garafola © Dehui Kong 1 B-Boy Infinitives To suck until our lips turned blue the last drops of cool juice from a crumpled cup sopped with spit the first Italian Ice of summer To chase popsicle stick skiffs along the curb skimming stormwater from Woodbridge Ave to Old Post Road To be To B-boy To be boys who snuck into a garden to pluck a baseball from mud and shit To hop that old man's fence before he bust through his front door with a lame-bull limp charge and a fist the size of half a spade To be To B-boy To lace shell-toe Adidas To say Word to Kurtis Blow To laugh the afternoons someone's mama was so black when she stepped out the car B-boy… that’s what it is, that’s why when the public the oil light went on changed it to ‘break-dancing’ they were just giving a To count hairs sprouting professional name to it, but b-boy was the original name for it and whoever wants to keep it real would around our cocks To touch 1 ourselves To pick the half-smoked keep calling it b-boy. True Blues from my father's ash tray and cough the gray grit - JoJo, from Rock Steady Crew into my hands To run my tongue along the lips of a girl with crooked teeth To be To B-boy To be boys for the ten days an 8-foot gash of cardboard lasts after we dragged that cardboard seven blocks then slapped it on the cracked blacktop To spin on our hands and backs To bruise elbows wrists and hips To Bronx-Twist Jersey version beside the mid-day traffic To swipe To pop To lock freeze and drop dimes on the hot pavement – even if the girls stopped watching and the street lamps lit buzzed all night we danced like that and no one called us home - Patrick Rosal 1 The Freshest Kids , prod. -

Mark III Owners Manual

MESA-BOOGIE MARK III OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS MESA ENGINEERING CONGRATULATIONS! You've just become the proud owner of the world's finest guitar amplifier. When people come up to compliment you on your tone, you can smile knowingly ... and hopefully you'll tell them a little about us! This amplifier has been designed, refined and constructed to deliver maximum musical performance of any style, in any situation. And in order to live up to that tall promise, the controls must be very powerful and sophisticated. But don't worry! Just by following our sample settings, you'll be getting great sounds immediately. And as you gain more familiarity with the Boogie's controls, it will provide you with much greater depth and more lasting satisfaction from your music. THREE MODES For approximately twelve years, the evolution of the guitar amplifier has largely been pioneered by MESA-Boogie. The Original Mark I Boogie was the first amplifier to offer successful lead enhancement. Then the Mark II Boogie was the first amplifier to introduce footswitching between lead and rhythm. Now your new Mark III offers three footswitchable modes of operation: Rhythm 1, Rhythm 2 and Lead. Rhythm 1 is primarily for playing bright and sparkling clean (although a little crunch is available by running the Volume at 10). You might think of Rhythm 1 as "the Fender mode”. Rhythm 2 is mainly for crunch chords, chunking metal patterns and some blues (but low settings of the Volume 1 will produce an alternate clean sound that is very fat and warm). Think of Rhythm 2 as "the Marshall mode". -

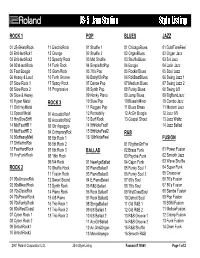

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

November / December 2017

November / December 2017 See Page 21 2 Love The Blues? Live The Blues? The Detroit Blues Society’s Lifetime Achievement Award Honorees Board of Directors 2017 President Steve Soviak 2013: [email protected] 2008: Vice President / Editor Jane Cassisi [email protected] 2006: 2005: Secretary William Toll [email protected] Director At Large Cynthia Davis [email protected] Director At Large Blues Horizon Award Winners Luther Keith [email protected] Joe Von Battle Director At Large Victoria Linsley 1993: [email protected] 1992: 2008: Committee Chairs - 2017 James S. Henry Award Winners 2010: Bryan Iglesias/Zerapath Membership - Tom McNab 2009: Jake Bishop 2005: Jeremy Haberman [email protected] Volunteer - Jane Cassisi New & Renewed Members from [email protected] August 10, 2017 to October 11, 2017 Blue Notes - Jane Cassisi [email protected] Street Team - Victoria Linsley Daniel & Deanna Adams, Elaine & Gerald Arnold, [email protected] B.J. Belcoure, Larry “Mugs” Benedict, Lars Bjorn, Website - William Toll [email protected] Alan Chunn, Larry Everhart, Ken Gilbert, Thomas Keating, Lynne Martinez, Doug Montgomery, Publicity – Cynthia Davis [email protected] Surayyah R Muwwakkil, Russ & Cindy Ortisi, Har- old Price, Robert Stevens and Randy Schwartz Blues Challenge - Steve Soviak [email protected] Youth Challenge - Cheri Lowe Our sincere appreciation goes out to all new and [email protected] renewing members. Daniel & Deanna Adams, B.J. Monthly Meetings/Jams - Jane Cassisi Belcoure, Lars Bjorn, Larry Everhart, Ken Gilbert [email protected] and Thomas Keating all took advantage of the dis- Victoria Linsley [email protected] count available with a multiple year membership. -

Chapter 4 Creolized Dance Music Text: Robin Moore Instructor’S Manual: Sarah J

Chapter 4 Creolized Dance Music Text: Robin Moore Instructor’s Manual: Sarah J. Bartolome All activities are keyed as follows: AA = All ages E = Elementary (particularly grades 3–6) S = Secondary (middle school and high school, grades 7–12) C/U = College and university Chapter 4 Vocabulary merengue, merengue típico, güira, marímbula, tambora, paseo, cuerpo, jaleo, apambichao, son, verso, canto, montuno, tres, tresero, martillo, bongsero, timbales, socialism, Cold War, plena, panderetas, panderos, seguidor, segunda, requinto, soneos, salsa, salsa dura, cáscara, salsa romántica, salsa monga, timba Exploring Traditional and Commercial Merengue (AA) Compare a traditional merengue with a commercially recorded merengue. 1. Watch the video of La India Canela performing merengue típico, available at http://www.folkways.si.edu/explore_folkways/video_caribbean.aspx. 2. Have students identify the instruments they see and hear. 3. Have students also watch the video of Johnny Ventura performing “Merenguero Hasta la Tambora,” available on YouTube at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7XzINu2ee4A. 4. Compare the two merengues. Draw students’ attention to differences in instrumentation and the commercialization of the latter performance. Exploring Merengue through Dance (AA) Learn the simple merengue dance movement. 1. Search on YouTube for an instructive video if you are not familiar with the basic step-together movement associated with merengue. One such video is available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=on4V1KN_Iuw. 2. Either teach the students yourself or learn with them as you watch the video. 3. Dance along to a recording of merengue, either in lines or in pairs as students are comfortable. Exploring Merengue: Form (A) 1. -

John Lee Hooker: King of the Boogie Opens March 29 at the Grammy Museum® L.A

JOHN LEE HOOKER: KING OF THE BOOGIE OPENS MARCH 29 AT THE GRAMMY MUSEUM® L.A. LIVE CONTINUING THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BIRTH OF LEGENDARY GRAMMY®-WINNING BLUESMAN JOHN LEE HOOKER, TRAVELING EXHIBIT WILL FEATURE RARE RECORDINGS AND UNIQUE ITEMS FROM THE HOOKER ESTATE; HOOKER'S DAUGHTERS, DIANE HOOKER-ROAN AND ZAKIYA HOOKER, TO APPEAR AT MUSEUM FOR SPECIAL OPENING NIGHT PROGRAM LOS ANGELES, CALIF. (MARCH 6, 2018) —To continue commemorating what would have been legendary GRAMMY®-winning blues artist John Lee Hooker’s 100th birthday, the GRAMMY Museum® will open John Lee Hooker: King Of The Boogie in the Special Exhibits Gallery on the second floor on Thursday, March 29, 2018. On the night of the opening, Diane Hooker-Roan and Zakiya Hooker, daughters of the late bluesman, will appear at the GRAMMY Museum for a special program. Presented in conjunction with the John Lee Hooker Estate and Craft Recordings, the exhibit originally opened at GRAMMY Museum Mississippi—Hooker's home state—in 2017, the year of Hooker's centennial. On display for a limited time only through June 2018, the exhibit will include, among other items: • A rare 1961 Epiphone Zephyr—one of only 13 made that year—identical to the '61 Zephyr played by John Lee Hooker. Plus, a prototype of Epiphone's soon-to-be-released Limited Edition 100th Anniversary John Lee Hooker Zephyr signature guitar • Instruments such as the Gibson ES-335, Hohner HJ5 Jazz, and custom Washburn HB35, all of which were played by Hooker • The Best Traditional Blues Recording GRAMMY Hooker won, with Bonnie Raitt, for "I'm In The Mood" at the 32nd Annual GRAMMY Awards in 1990 • Hooker's Best Traditional Blues Album GRAMMY for Don't Look Back, which was co-produced by Van Morrison and Mike Kappus and won at the 40th Annual GRAMMY Awards in 1998 • A letter to Hooker from former President Bill Clinton • The program from Hooker's memorial service, which took place on June 27, 2001, in Oakland, Calif. -

San Diego's Queen of the Boogie Woogie

by Put Kramer Sue Palmer Sun Diego's Qaeen of Boogie Woogie rflhirty years in lhe mustc Sue's first professional I indrrt.y is a long time band was in Tobacco Road, for any performer, particular- a band she formed with well ly for blues artists and espe- known jazz and swing bass cially for women blues per- player Preston Coleman. formers. For Sue Palmer, the Over the next 15 years, the "Queen of Boogie Woogie," band played regular gigs at it's been a star-studded blues the Belly Up Tavern in So- career with many rewards lano Beach. Of Coleman she and awards. The swing, blues says, "Working with Preston and boogie-woogie piano was like going to college to player has toured the world learn my craft. He was the and played music festivals real thing - a man who was throughout the U.S. and Eu- a fantastic performer and ar- rope as the pianist for blues ranger and was kind and gen- diva Candye Kane. But it's erous with us." her solo and band recording While fronting Tobacco as Sue Palmer and Her Mo- Road, Sue met Candye Kane tel Swing Orchestra that have and soon after the two be- generated the most awards. gan collaborating on music. Her fourth release, Sophisti- Later, Sue was invited to join cated Lady won an Interna- Kane's band as piano player tional Blues Challenge Award which led to world tours for "Best Self Produced CD" through the '90s playing club in 2008, her third release, dates and festivals in Canada, Live at Dizzy's won "Best Australia, France, Holland, Blues Album 200212003" the Netherlands and United and her solo piano album, States. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Chicago Blues Guitar

McKinley Morganfield (April 4, 1913 – April 30, 1983), known as Muddy WatersWaters, was an American blues musician, generally considered the Father of modern Chicago blues. Blues musicians Big Bill Morganfield and Larry "Mud Morganfield" Williams are his sons. A major inspiration for the British blues explosion in the 1960s, Muddy was ranked #17 in Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time. Although in his later years Muddy usually said that he was born in Rolling Fork, Mississippi in 1915, he was actually born at Jug's Corner in neighboring Issaquena County, Mississippi in 1913. Recent research has uncovered documentation showing that in the 1930s and 1940s he reported his birth year as 1913 on both his marriage license and musicians' union card. A 1955 interview in the Chicago Defender is the earliest claim of 1915 as his year of birth, which he continued to use in interviews from that point onward. The 1920 census lists him as five years old as of March 6, 1920, suggesting that his birth year may have been 1914. The Social Security Death Index, relying on the Social Security card application submitted after his move to Chicago in the mid '40s, lists him as being born April 4, 1915. His grandmother Della Grant raised him after his mother died shortly after his birth. His fondness for playing in mud earned him the nickname "Muddy" at an early age. He then changed it to "Muddy Water" and finally "Muddy Waters". He started out on harmonica but by age seventeen he was playing the guitar at parties emulating two blues artists who were extremely popular in the south, Son House and Robert Johnson. -

Chasing the Echoes in Search of John Lee Hooker’S Detroit by Jeff Samoray

Chasing the Echoes In search of John Lee Hooker’s Detroit by jeff samoray n September of 1948, John Lee Hooker strummed the chord bars, restaurants, shoeshine parlors and other businesses that made up that ignited the endless boogie. Like many Delta blues musicians the neighborhood — to make way for the Chrysler Freeway. The spot I of that time, Hooker had moved north to pursue his music, and he where Hooker’s home once stood is now an empty, weed-choked lot. was paying the bills through factory work. For five years he had been Sensation, Fortune and the other record companies that issued some of toiling as a janitor in Detroit auto and steel plants. In the evenings, he Hooker’s earliest 78s have long been out of business. Most of the musi- would exchange his mop and broom for an Epiphone Zephyr to play cians who were on the scene in Hooker’s heyday have died. rent parties and clubs throughout Black Bottom, Detroit’s thriving Hooker left Detroit for San Francisco in 1970, and he continued black community on the near east side. “doin’ the boogie” until he died in 2001, at age 83. An array of musi- Word had gotten out about Hooker’s performances — a distinct, cians — from Eric Clapton and Bonnie Raitt to the Cowboy Junkies primitive form of Delta blues mixed with a driving electric rhythm. and Laughing Hyenas — have covered his songs, yet, for all the art- After recording a handful of crude demos, he finally got his break. ists who have followed in Hooker’s footsteps musically, it’s not easy to Hooker was entering Detroit’s United Sound Systems to lay down his retrace his path physically in present-day Detroit. -

Music 3500: American Music This Final Exam Is Comprehensive —It Covers the Entire Course (Monday December Starting at 5PM In

FINAL EXAM STUDY GUIDE Music 3500: American Music This final exam is comprehensive —it covers the entire course (Monday December starting at 5PM in Knauss Hall 2452) Exam Format: 70 questions (each question is worth 4 points), plus a 40-point "fill-in-the-chart" (described below) (these two things total a maximum of 320 possible points toward your final course grade total). The format of the 70-question computer-graded section of the final exam will be: ...Matching ...Multiple Choice ...True/False (from text readings, class lectures, YouTube video links) General study recommendations: - Do the online quiz assignments for Chapters 1-9 (these must be completed by Monday April 24) ---------- For the Computer-Graded part of the final exam: 1. Know the definitions of Important Terms at the ends of Chapters 2-8 - Chapter 1 (textbook, page 5) -- know "popular music," "roots music," "Classical art- music" - Chapter 2 (textbook, page 19) -- know "old-time music," "hot jazz," "race music" - Chapter 3 (textbook, page 31) -- know "bebop," "big-band," "boogie-woogie" - Chapter 4 (textbook, page 42) -- know "backbeat," "chance music," "cool jazz," "multi- serialism," "rhythm & blues," "soul" - Chapter 5 (textbook, page 52) -- know "soundtrack," "free jazz" - Chapter 6 (textbook, pages 58-59) -- know "fusion," minimalism," - Chapter 7 (textbook, pages 69-70) -- know "techno," "smooth jazz," "hip-hop" - Chapter 8 (textbook, page 81) -- know "sound art" 2. Know which decade the following music technologies came from: (Review the chronological order of -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contacts Heather Pease, Breckenridge Creative Arts 970 453 3187 ext 3 | [email protected] Nancy Rebek, NRPR 303 941 2527 | [email protected] BCA Presents JOHN HIATT AND THE COMBO Acclaimed musician, singer and songwriter John Hiatt and his band come to Breckenridge Monday, September 21, 2015 at 7:30 pm Tickets: $55, $75 Riverwalk Center, Breckenridge "(Hiatt) writes the funniest sad songs – and the saddest funny songs – of just about anybody alive.” –Los Angeles Times BRECKENRIDGE, CO (June 19, 2015) – Breckenridge Creative Arts is proud to present songwriting legend John Hiatt and the Combo on Monday, September 21, 2015 at 7:30 pm at the Riverwalk Center in Breckenridge. Tickets are priced at $55 and $75 for gold circle seats (first four rows, center section) and are on sale now at the Riverwalk Center Ticket Office, by phone at 970-547-3100 or online at breckcreate.org. John Hiatt's career as a performer and songwriter has spanned more than 30 years and everyone from Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, BB King, Bonnie Raitt, and Iggy Pop has covered his work. The Los Angeles Times calls him “…one of rock’s most astute singer-songwriters of the last 40 years,” after the release of his newest album Terms Of My Surrender, last summer via New West Records. Hiatt, a master lyricist and satirical storyteller, weaves hidden plot twists into fictional tales ranging in topics including redemption, relationships, growing older and surrendering, on his terms. This new record is musically rooted in acoustic blues, accentuated by Hiatt’s soulful, gritty voice, which mirrors the gravity of his reflective lyrics.