Chasing the Echoes in Search of John Lee Hooker’S Detroit by Jeff Samoray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Cultural Justice Approach to Popular Music Heritage in Deindustrialising Cities

International Journal of Heritage Studies ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjhs20 A cultural justice approach to popular music heritage in deindustrialising cities Zelmarie Cantillon , Sarah Baker & Raphaël Nowak To cite this article: Zelmarie Cantillon , Sarah Baker & Raphaël Nowak (2020): A cultural justice approach to popular music heritage in deindustrialising cities, International Journal of Heritage Studies, DOI: 10.1080/13527258.2020.1768579 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1768579 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 27 May 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 736 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjhs20 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HERITAGE STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1768579 A cultural justice approach to popular music heritage in deindustrialising cities Zelmarie Cantillon a,b, Sarah Baker c and Raphaël Nowak b aInstitute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University, Parramatta, Australia; bGriffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia; cSchool of Humanities, Languages and Social Science, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Deindustrialisation contributes to significant transformations for local Received 2 April 2020 communities, including rising unemployment, poverty and urban decay. Accepted 10 May 2020 ‘ ’ Following the creative city phenomenon in cultural policy, deindustrialis- KEYWORDS ing cities across the globe have increasingly turned to arts, culture and Cultural justice; popular heritage as strategies for economic diversification and urban renewal. -

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

John Lee Hooker: King of the Boogie Opens March 29 at the Grammy Museum® L.A

JOHN LEE HOOKER: KING OF THE BOOGIE OPENS MARCH 29 AT THE GRAMMY MUSEUM® L.A. LIVE CONTINUING THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BIRTH OF LEGENDARY GRAMMY®-WINNING BLUESMAN JOHN LEE HOOKER, TRAVELING EXHIBIT WILL FEATURE RARE RECORDINGS AND UNIQUE ITEMS FROM THE HOOKER ESTATE; HOOKER'S DAUGHTERS, DIANE HOOKER-ROAN AND ZAKIYA HOOKER, TO APPEAR AT MUSEUM FOR SPECIAL OPENING NIGHT PROGRAM LOS ANGELES, CALIF. (MARCH 6, 2018) —To continue commemorating what would have been legendary GRAMMY®-winning blues artist John Lee Hooker’s 100th birthday, the GRAMMY Museum® will open John Lee Hooker: King Of The Boogie in the Special Exhibits Gallery on the second floor on Thursday, March 29, 2018. On the night of the opening, Diane Hooker-Roan and Zakiya Hooker, daughters of the late bluesman, will appear at the GRAMMY Museum for a special program. Presented in conjunction with the John Lee Hooker Estate and Craft Recordings, the exhibit originally opened at GRAMMY Museum Mississippi—Hooker's home state—in 2017, the year of Hooker's centennial. On display for a limited time only through June 2018, the exhibit will include, among other items: • A rare 1961 Epiphone Zephyr—one of only 13 made that year—identical to the '61 Zephyr played by John Lee Hooker. Plus, a prototype of Epiphone's soon-to-be-released Limited Edition 100th Anniversary John Lee Hooker Zephyr signature guitar • Instruments such as the Gibson ES-335, Hohner HJ5 Jazz, and custom Washburn HB35, all of which were played by Hooker • The Best Traditional Blues Recording GRAMMY Hooker won, with Bonnie Raitt, for "I'm In The Mood" at the 32nd Annual GRAMMY Awards in 1990 • Hooker's Best Traditional Blues Album GRAMMY for Don't Look Back, which was co-produced by Van Morrison and Mike Kappus and won at the 40th Annual GRAMMY Awards in 1998 • A letter to Hooker from former President Bill Clinton • The program from Hooker's memorial service, which took place on June 27, 2001, in Oakland, Calif. -

88-Page Mega Version 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010

The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! 88-PAGE MEGA VERSION 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 COMBINED jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! INDEX 2017 Gift Guide •••••• 3 2016 Gift Guide •••••• 9 2015 Gift Guide •••••• 25 2014 Gift Guide •••••• 44 2013 Gift Guide •••••• 54 2012 Gift Guide •••••• 60 2011 Gift Guide •••••• 68 2010 Gift Guide •••••• 83 jazz &blues report jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com 2017 Gift Guide While our annual Gift Guide appears every year at this time, the gift ideas covered are in no way just to be thought of as holiday gifts only. Obviously, these items would be a good gift idea for any occasion year-round, as well as a gift for yourself! We do not include many, if any at all, single CDs in the guide. Most everything contained will be multiple CD sets, DVDs, CD/DVD sets, books and the like. Of course, you can always look though our back issues to see what came out in 2017 (and prior years), but none of us would want to attempt to decide which CDs would be a fitting ad- dition to this guide. As with 2016, the year 2017 was a bit on the lean side as far as reviews go of box sets, books and DVDs - it appears tht the days of mass quantities of boxed sets are over - but we do have some to check out. These are in no particular order in terms of importance or release dates. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

BLUES UNLIMITED Number Four (August 1963)

BLUES UN LI Ml TED THE JOURNAL OF “THE BLUES APPRECIATION SOCIETY” EDITED BY SIMON A. NAPIER - Jiiiiffiber Four August 196^ ; purposes of ^'HLues Unlimited* &re several-fold* To find out more about tlse singers is : §1? iiaportant one* T® document th e ir records . equally so,, This applies part!cularly with .postwar "blues ' slmgers and labels. Joho Godrieh m d Boh Dixon ? with the Concert ed help> o f many collectors? record companies imd researchers* .^aTe/v.niide^fHitpastri'Q. p|»©gr;e8Sv, In to l i ‘s.ting. the blues records made ■ parlor to World War IXa fn a comparatively short while 3 - ’with & great deal of effort,.they have brought the esad of hlues discog raphy prewar- in sights Their book?. soon t® be published, w ill be the E?5?st valuable aid. 't o blues lovers yet compiled,, Discography of-;p©:stw£sr ...artists....Is,.In.-■■. a fa r less advanced state* The m&gasine MBlues Research1^ is doing. amagni fieezst- ^ob with : postwar blues;l^bei:s:^j Severd dis^grg^hers are active lis tin g the artists' work* We are publishing Bear-complete discographies xb the hope that you3 the readers^ w ill f i l l In the gaps* A very small proportion o f you &re: helping us in this way0 The Junior Farmer dis&Oc.: in 1 is mow virtu ally complete« Eat sursiy . :s®eb®ciy,:h&s; Bake^;31^;^: 33p? 3^o :dr3SX* Is i t you? We h&veii#t tie&rd from y<&ia£ Simil^Xy: ^heM. -

1971-06-05 the Main Point-Page 20

08120 JUNE 5, 1971 $1.25 A BILLBOARD PUBLICATION t..bl)b;,!RIKE100*-ri.3wZ9 F _) 72 ">¡Ai'2(HAl\I; J 4A1-EN SEVENTY -SEVENTH YEAR BOX 10005 The International i i;N;lEf?. CO 80210 Music-Record-Tape Newsweekly CARTRIDGE TV PAGE 16 HOT 100 PAGE 56 TOP LP'S PAGES 54, 55 C S Sales Soari Car Tapes osts p Puts Pub on ® 5 >s .f*'? Sets bîversiIîc .p t® Sign on rk; Asks 5 Mil By LEE ZHITO By MIKE GROSS NEW YORK - CBS Inter- and today has expanded its own- Ci;ssette Units national enters its second decade ership in foreign subsidiaries to NEW YORK -Capitol Rec- operation of the Capitol Record with an estimated $100 million 24 countries. Its representation By RADCLIFFE JOE ords is planning to unload Club. in annual sales, and a program in the international marketplace NEW YORK - Car Tapes, its music publishing division, Bhaskar Menon, newly ap- - Glenwood Music. of accelerated expansion and consists of countries which are Inc. will phase out two of its Beechwood of Capitol diversification. The asking price for the firm is pointed president responsible for approximately 95 three auto cassette units, pos- up The company started with percent of the record industry's reported to be $5 million. One Records, has been shaking sibly by year's end. The Cali- picture firms in three countries abroad, dollar volume outside of the fornia -based company had three of the bids under consideration the diskery's structural U.S. with price tags has come from Longine's, which during the past few weeks and units available of publishing t' : Harvey Schein, president of $80 to $160. -

John Lee Hooker 1991.Pdf

PERFORMERS John Lee Hooker BY JOHN M I L W A R D H E BLUES ACCORDING TO John Lee Hooker is a propulsive drone of a guitar tuned to open G, a foot stomping out a beat that wouldn’t know how to quit, and a bear of a voice that knows its way around the woods. He plays big-city, big-beat blues born in the Mississippi Delta. Blame it on the boogie, and you’re blaming it on John Lee Hooker. Without the music of John Lee Hooker, Jim Morrison two dozen labels, creating one of the most confusing wouldn’t have known of crawling kingsnakes, and George discographies in blues history. Hooker employed such Thorogood wouldn’t have ordered up “One Bourbon, One pseudonyms as Texas Slim, Birmingham Sam, Delta John, Scotch, One Beer.” Van Morrison would not have influenced John Lee Booker, and Boogie Man. Most of his rhythm & generations of rock singers by personalizing the idiosyncratic blues hits appeared on Vee jay Records, including “Crawlin’ emotional landscape of Hooker’s fevered blues. Kingsnake,” "No Shoes,” and “Boom Boom”—John Lee’s sole Hooker inspired these and countless other boogie chil entry on the pop singles chart, in 1962. dren with blues that don’t In the late ’50s, Hooker adhere to a strict 12-bar T H E BLUES ALONE found a whole new audience structure, but move in re Detroit businessman Bernard Besman (in partnership with club owner Lee among the white fans of the sponse to the singer’s singu Sensation) issued John Lee Hooker’s first records in 1948 on the Sensation la folk revival. -

Detroit Media Guide Contents

DETROIT MEDIA GUIDE CONTENTS EXPERIENCE THE D 1 Welcome ..................................................................... 2 Detroit Basics ............................................................. 3 New Developments in The D ................................. 4 Destination Detroit ................................................... 9 Made in The D ...........................................................11 Fast Facts ................................................................... 12 Famous Detroiters .................................................. 14 EXPLORE DETROIT 15 The Detroit Experience...........................................17 Dearborn/Wayne ....................................................20 Downtown Detroit ..................................................22 Greater Novi .............................................................26 Macomb ....................................................................28 Oakland .....................................................................30 Itineraries .................................................................. 32 Annual Events ..........................................................34 STAYING WITH US 35 Accommodations (by District) ............................. 35 NAVIGATING THE D 39 Metro Detroit Map ..................................................40 Driving Distances ....................................................42 District Maps ............................................................43 Transportation .........................................................48 -

Michigan Statewide Preservation Plan 2020-2025

Michigan Statewide Historic Preservation Plan 2020-2025 [COVER PHOTO] 1 State Historic Preservation Office Michigan Economic Development Corporation 300 N. Washington Square Lansing, Michigan 48913 Brian D. Conway, State Historic Preservation Officer Jeff Mason, CEO, Michigan Economic Development Corporation Gretchen Whitmer, Governor, State of Michigan Prepared by Amy L. Arnold, Preservation Planner Michigan State Historic Preservation Office Lansing, Michigan December 2019 With assistance from Peter Dams, Dams & Associates This report has been financed entirely with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or you desire further information, please write to: Office for Equal Opportunity National Park Service 1849 C Street, N.W. Washington D.C. 20240 2 Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………… Vision………………………………………………………………………… Goal Summary Page…………………………………………………………. Working Together – Stories of Success 2014-2019 …………………………… A Look to the Future: Challenges and Opportunities……………………….…. Goals and Objectives……………………………………………………………. Goal 1: Targeted Preservation Education……………………………………... Goal2: Expand Preservation Funding Opportunities………………………… Goal 3: Increase Diversity in Historic Preservation…………………………. Goal 4: Build Stronger Partnerships…………………………………………. -

Roots of Aretha Franklin, Proletarian Culture and the Rise of Black Detroit

Roots of Aretha Franklin, Proletarian Culture and the Rise of Black Detroit Queen of Soul was an outstanding manifestation of the African American struggle for dignity and freedom By Abayomi Azikiwe Region: USA Global Research, August 18, 2018 Theme: History, Police State & Civil Rights, Poverty & Social Inequality Note to readers: please click the share buttons above Detroit artist and social activist Aretha Franklin passed into her ancestral realm on Wednesday morning August 16 while surrounded by family and friends in her Detroit Riverfront condominium downtown. It had been announced the previous week that Aretha was gravely ill and was hospitalized. Later press accounts indicated that she was checked out of the hospital and sent home possibly under hospice care. These were difficult reports for many people in the Detroit area to accept at their face value. The Queen of Soul had been ill in the past and hospitalized. Several years before, media accounts claimed she was suffering from pancreatic cancer and was terminal. However, contradictory claims publicized through television, radio, print and internet platforms said these reports were unsubstantiated. | 1 Several weeks later Aretha was seen attending a Piston’s basketball game at the Palace in Auburn Hills. Although she had lost considerable weight, her appearance and activity illustrated that the Queen was by no means making an immediate exit from the stage. Just last year in June (2017), Aretha was honored in downtown Detroit through the renaming of a street after her while on the same day performing a free concert for the people of the city. Long term friends of Aretha such as Mary Wilson, formerly of the Supremes, Freda Payne, solo vocalist, the boxing champion Tommy Hearns and the Rev. -

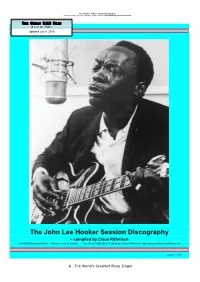

Complete John Lee Hooker Session Discography

The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography: from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info The Great R&B Files (# 2 of 12) PaRT i Updated July 8, 2019 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography - compiled by Claus Röhnisch The R&B Pioneers Series – Volume Two of twelve The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info page 1 (94) 1 The World’s Greatest Blues Singer The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography: from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info The John Lee Hooker Session Discography - compiled by Claus Röhnisch John Lee Hooker – The World’s Greatest Blues Singer / The R&B Pioneers Series – Volume Two of twelve Below: Hooker’s first record, his JVB single of 1953, and the famous “Boom Boom”. The “Hooker” Box, Vee-Jay’s version of the Hooker classic, the original “The Healer” album on Chameleon. BluesWay 1968 single “Mr. Lucky”, the Craft Recordings album of March 2017, and the French version of the Crown LP “The Blues”. Right: Hooker in his prime. Two images from Hooker’s grave in the Chapel of The Chimes, Oakland, California; and a Mississippi Blues Trail Marker on Hwy. 3 in Quitman County (Vance, Missisippi memorial stone - note birth date c. 1917). 2 The World’s Greatest Blues Singer The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography: from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info . December 31, 1948 (probably not, but possibly early 1949) - very rare (and very early) publicity photo of the new-found Blues Star (playin’ his Gibson ES 175).